It’s not often that you see infographics with soul. Even though visuals are significantly more fun to look at than actual data tables, the oversimplification of infographics tends to suck out the interest in favor of making things quickly comprehensible (often to the detriment of the true data points, like the 2000 election map). This Röyksopp video, on the other hand, a delightful crossover between games, illustration, and infographic, is all about the storyline and subverts data to be a secondary player. This is not pure data visualization on the lines of the front page feature in USA Today. It is, instead, a touching story encased in the traditional visual language and iconography of infographics. The video’s currency belies its age: it won the 2002 MTV Europe music video award for best video.

Our information environment is growing both more dispersed and more saturated. Infographics serve as a filter, distilling hundreds of data points down into comprehensible form. They help us peer into the impenetrable data pools in our day to day life, and, in the best case, provide an alternative way to reevaluate our surroundings and make better decisions. (Tufte has also famously argued that infographics can be used to make incredibly poor decisions–caveat lector.)

But infographics do something else; more than visual representations of data, they are beautiful renderings of the invisible and obscured. They stylishly separate signal from noise, bringing a sense of comprehensive simplicity to an overstimulating environment. That’s what makes the video so wonderful. In the non-physical space of the animation, the datasphere is made visible. The ambient informatics reflect the information saturation that we navigate everyday (some with more serenity than others), but the woman in the video is unperturbed by the massive complexity of the systems that surround her. Her bathroom is part of a maze of municipal waterpipes; she navigates the public transport grid with thousands of others; she works at a computer terminal dealing with massive amounts of data (which are rendered in dancing—and therefore somewhat useless—infographics for her. A clever wink to the audience.); she eats food from a worldwide system of agricultural production that delivers it to her (as far as she can tell) in mere moments. This is the complexity that we see and we know and we ignore, just like her. This recursiveness and reference to the real is deftly handled. The video is designed to emphasize the larger picture and allows us to make connections without being visually bogged down in the particulars and textures of reality. The girl’s journey from morning to pint is utterly familiar, yet rendered at this larger scale and with the pointed clarity of a information graphic, the narrative is beautiful and touching.

via information aesthetics

Category Archives: video

net-based video creates bandwidth crunch

Apparently the recent explosion of internet video services like YouTube and Google Video has led to a serious bandwidth bottleneck on the network, potentially giving ammunition to broadband providers in their campaign for tiered internet service.

If Congress chooses to ignore the cable and phone lobbies and includes a network neutrality provision in the new Telecommunications bill, that will then place the burden on the providers to embrace peer-to-peer technologies that could solve the traffic problem. Bit torrent, for instance, distributes large downloads across multiple users in a local network, minimizing the strain on the parent server and greatly speeding up the transfer of big media files. But if govenment capitulates, then the ISPs will have every incentive to preserve their archaic one-to-many distribution model, slicing up the bandwidth and selling it to the highest bidder — like the broadcast companies of old.

The video bandwidth crunch and the potential p2p solution nicely illustrates how the internet is a self-correcting organic entity. But the broadband providers want to seize on this moment of inneficiency — the inevitable rise of pressure in the pipes that comes from innovation — and exploit it. They ought to remember that the reason people are willing to pay for broadband service in the first place is because they want access to all the great, innovative stuff developing on the net. Give them more control and they’ll stifle that innovation, even as they say they’re providing better service.

subtitles and the future of reading

After enduring a weeks-long PR pummeling for its dealings in China, Google is hard at work to improve its image in the world, racking up some points for good after slipping briefly into evil. Recently they launched Google.org: a website for the Google Foundation, the corporation’s philanthropic arm and central office of evil mitigation. Paying a visit to the site, the disillusioned among us will be pleased to find that the foundation is already sponsoring a handful of worthy initiatives, along with a grants program that donates free web advertising to nonprofit organizations. And just in case we were concerned that Google might not apply its techno-capitalist wizardry to altruism as zealously as to making profit, they just announced today they’ve named a new director for the foundation by the name of — no joke — Dr. Brilliant. So it seems the world is in capable hands.

One project in particular caught my eye in light of recent discussions about screen-based reading and genre-blending visions of the book. Planet Read is an organization that promotes literacy in India through Same Language Subtitling — a simple but apparently effective technique for building basic reading skills, taking popular visual entertainment like Bollywood movies and adding subtitles in English and Hindi along the bottom of the screen. A number of samples (sadly no Bollywood, just videos or photo montages set to Indian folk songs) can be found on Google Video. Here’s one that I particularly liked:

Watching the video — managing the interplay between moving text and moving pictures — I began to wonder whether there are possibly some clues to be mined here about the future of reading. Yes, Planet Read is designed first and foremost to train basic alphabetic literacy, turning a captive audience into a captive classroom. But in doing so, might it not also be nurturing another kind of literacy?

The problem with contemporary discussions about the future of the book is that they are mired — for cultural and economic reasons — in a highly inflexible conception of what a book can be. People who grew up with print tend to assume that going digital is simply a matter of switching containers (with a few enhancements thrown in the mix), failing to consider how the actual content of books might change, or how the act of reading — which increasingly takes place in a dyanamic visual context — may eventually demand a more dynamic kind of text.

Blurring the lines between text and visual media naturally makes us uneasy because it points to a future that quite literally (for us dinosaurs at least) could be unreadable. But kids growing up today, in India or here in the States, are already highly accustomed to reading in screen-based environments, and so they probably have a somewhat different idea of what reading is. For them, text is likely just one ingredient in a complex combinatory medium.

Another example: Nochnoi Dozor (translated “Night Watch”) is a film that has widely been credited as the first Russian blockbuster of the post-Soviet era — an adrenaline-pumping, special effects-infused, sci-fi vampire epic made entirely by Russians, on Russian soil and on Russian themes (it’s based on a popular trilogy of novels). When it was released about a year and a half ago it shattered domestic box office records previously held by Western hits like Titanic and Lord of the Rings. Just about a month ago, the sequel “Day Watch” shattered the records set by “Night Watch.”

While highly derivative of western action movies, Nochnoi Dozor is moody, raucous and darkly gorgeous, giving a good, gritty feel of contemporary Moscow. Its plot grows rickety in places, and sometimes things are downright incomprehensible (even, I’m told, with fluent Russian), so I’m skeptical about its prospects on this side of the globe. But goshdarnit, Russians can’t seem to get enough of it — so in an effort to lure American audiences over to this uniquely Russian gothic thriller, start building a brand out of the projected trilogy (and presumably pave the way for the eventual crossover to Hollywood of director Timur Bekmambetov), Fox Searchlight just last week rolled the film out in the U.S. on a very limited release.

What could this possibly have to do with the future of reading? Well, naturally the film is subtitled, and we all know how subtitles are the kiss of death for a film in the U.S. market (Passion of the Christ notwithstanding). But the marketers at Fox are trying something new with Nochnoi Dozor. No, they weren’t foolish enough to dub it, which would have robbed the film of the scratchy, smoke-scarred Moscow voices that give it so much of its texture. What they’ve done is played with the subtitles themselves, making them more active and responsive to the action in the film (sounds like some Flash programmer had a field day…). Here’s a description from an article in the NY Times (unfortunately now behind pay wall):

…[the words] change color and position on the screen, simulate dripping blood, stutter in emulation of a fearful query, or dissolve into red vapor to emulate a character’s gasping breaths.

And this from Anthony Lane’s review in the latest New Yorker:

…the subtitles, for instance, are the best I have encountered. Far from palely loitering at the foot of the screen, they lurk in odd corners of the frame and, at one point, glow scarlet and then spool away, like blood in water. I trust that this will start a technical trend and that, from here on, no respectable French actress will dream of removing her clothes unless at least three lines of dialogue can be made to unwind across her midriff.

It might seem strange to think of subtitling of foreign films as a harbinger of future reading practices. But then, with the increasing popularity of Asian cinema, and continued cross-pollination between comics and film, it’s not crazy to suspect that we’ll be seeing more of this kind of textual-visual fusion in the future.

Most significant is the idea that the text can itself be an actor in a perfomance: a frontier that has only barely been explored — though typography enthusiasts will likely pillory me for saying so.

video ipod

Looks like it’s hardware day at if:book. Just got a video iPod. Hmmm. this looks like another niche where Apple has handily beat Sony. the image is crisper and larger than i expected; the case is slimmer and lighter.

it’s remarkably easy to convert video files to MP4 and load them onto the iPod. the experience is intimate . i’m experimenting with different genres, poetry, animation, family home video, short films. everything works. the iPod got handed around from ben to dan to ray to jesse. we came up with a bunch of ideas for projects we want to try. stay tuned.

war on text?

Last week, there was a heated discussion on the 1600-member Yahoo Groups videoblogging list about the idea of a videobloggers launching a “war on text” — not necessarily calling for book burning, but at least promoting the use of threaded video conversations as a way of replacing text-based communication online. It began with a post to the list by Steve Watkins and led to responses such as this enthusiastic embrace of the end of using text to communicate ideas:

Audio and video are a more natural medium than text for most humans. The only reason why net content is mainly text is that it’s easier for programs to work with — audio and video are opaque as far as programs are concerned. On top of that, it’s a lot easier to treat text as hypertext, and hypertext has a viral quality.

As a text-based attack on the printed work, the “war on text” debate had a Phaedrus aura about it, especially since the vloggers seemed to be gravitating towards the idea of secondary orality originally proposed by Walter Ong in Orality and Literacy — a form of communication which is involved at least the representation of an oral exchange, but which also draws on a world defined by textual literacy. The vlogger’s debt to the written word was more explicitly acknowledged some posts, such as one by Steve Garfield that declared his work to be a “marriage of text and video.”

Over several days, the discussion veered to cover topics such as film editing, the over-mediation of existence, and the transition from analog to digital. The sophistication and passion of the discussion gave a sense of the way at least some in the video blogging community are thinking, both about the relationship between their work and text-based blogging and about the larger relationship between the written word and other forms of digitally mediated communication.

Perhaps the most radical suggestion in the entire exchange was the prediction that video itself would soon seem to be an outmoded form of communication:

in my opinion, before video will replace text, something will replace video…new technologies have already been developed that are more likely to play a large role in communications over this century… how about the one that can directly interface to the brain (new scientist reports on electroencephalography with quadriplegics able to make a wheelchair move forward, left or right)… considering the full implications of devices like this, it’s not hard to see where the real revolutions will occur in communications.

This comment implies that debates such as the “war on text” are missing the point — other forms of mediation are on the horizon that will radically change our understanding of what “communication” entails, and make the distinction between orality and literacy seem relatively miniscule. It’s an apocalyptic idea (like the idea that the internet will explode), but perhaps one worth talking about.

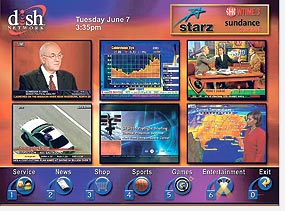

convergence sighting: the multi-channel tv screen

Several new “interactive television” services are soon to arrive that offer “mosaic” views of multiple channels, drawing TV ever nearer to full adoption of the browser, windows, and aggregator paradigms of the web (more in WSJ). It seems that once television is sufficiently like the web, it will simply be the web, or one province thereof.