Borders, in partnership with Lulu.com, has launched a comprehensive personal publishing platform, enabling anyone to design and publish their own (print) book and have it distributed throughout the Borders physical and online retail chain. Beyond the basic self-publishing tools, authors can opt for a number of service packages: simple ISBN registration (49 bucks), the basic package ($299), in which someone designs and formats your book for you, and the premium ($499), in which you get all the afore-mentioned plus “editorial evaluation.” According to the demo, you can even pay to have your own book tour and readings in actual Borders stores, bringing vanity publishing to a whole new level of fantasy role-playing. Writing and publishing, as the Borders site proclaims in its top banner, is now a “lifestyle.”

A side thought. It’s curious how “vanity publishing” as a cultural category seems to have a very clear relationship with the print book but a far more ambiguous one with the digital. Of course the Web as a whole could be viewed as one enormous vanity press, overflowing with amateur publishers and self-appointed authors, yet for some reason the vanity label is seldom applied -? though a range of other, comparable disparagements (“cult of the amateur”, “the electronic mob” etc.) sometimes are. But these new labels tend to be issued in a reactionary way, not with the confident, sneering self-satisfaction that has usually accompanied noses snobbishly upturned at the self-published.

A side thought. It’s curious how “vanity publishing” as a cultural category seems to have a very clear relationship with the print book but a far more ambiguous one with the digital. Of course the Web as a whole could be viewed as one enormous vanity press, overflowing with amateur publishers and self-appointed authors, yet for some reason the vanity label is seldom applied -? though a range of other, comparable disparagements (“cult of the amateur”, “the electronic mob” etc.) sometimes are. But these new labels tend to be issued in a reactionary way, not with the confident, sneering self-satisfaction that has usually accompanied noses snobbishly upturned at the self-published.

In the realm of print, there is (or traditionally has been) something vain, pretentious, even delusional, in the laying out of cash to simulate a kind of publication that is normally granted, by the forces of economics and cultural arbitration, to a talented or lucky few. Of course, so-called vanity publishing can also come from a pure impulse to get something out into the world that no one is willing to pay for, but generally speaking, it is something we’ve looked down on. Blogs, MySpace, personal web pages and the like arise out of a different set of socio-economic conditions. The barriers to publication are incredibly low (digital divide notwithstanding), and so authorship online is perceived differently than in print, even if it still arises out of the same basic need to communicate. It feels more like simply taking part in a conversation, participating in a commons. One is not immediately suspicious of the author’s credibility in quite the same way as when the self-financed publication is in print.

This is not to suggest that veracity, trust and quality control are no longer concerns on the Web. Quite the contrary. In fact we must develop better and more sensitive instruments of bullshit detection than ever before to navigate a landscape that lacks the comfortingly comprehensive systems of filtering and quality control that the publishing industry traditionally provided. But “vanity publishing” as a damning label, designed to consign certain types of books to a fixed cultural underclass, loses much of its withering power online. Electronic authorship comes with the possibility of social mobility. What starts as a vanity operation can, with time, become legitimized and respected through complex social processes that we are only beginning to be able to track. Self-publishing is simply a convenient starter mechanism, not a last resort for the excluded.

And with services like Lulu and the new Borders program, we’re seeing some of that social mobility reflected back onto print. New affordances of digital production and the flexibility of print on demand have radically lowered the barriers to publishing in print as well as in bits, and so what was once dismissed categorically as vanity is now transforming into a complex topography of niche markets where unmet readerly demands can finally be satisfied by hitherto untapped authorial supplies.

All the world’s a vanity press and we have to learn to make sense of what it produces.

Category Archives: lulu

amazon on demand

CustomFlix, Amazon’s on-demand DVD distribution service, has just been rebranded as CreateSpace, and will now serve up self-published media of all types. Getting a title into the system is free and relatively simple. Books must be a minimum of 24 pages and have to be submitted as a PDF. Seven trim sizes are available for color interiors, five for black and white. Each title automatically receives an ISBN and is displayed to shoppers as “in stock,” available for shipping immediately. You set the list price on your media, Amazon sets the selling price. CreateSpace is listed as the publisher of the book unless you provide your own ISBN, in which case you can appear under your own imprint.

CreateSpace titles apparently are eligible for the SearchInside browsing program (I wonder what the threshhold, or price, for entry is). I assume they will also be open for reader reviews, ratings and such. One thing I’d be very curious to know, however, is whether, or to what extent, CreateSpace titles will get factored into the social filtering and recommendation engines that power Amazon’s browsing experience. In some ways, that would be the best indicator of how much this move will blur the lines – ?in the perceptions of readers – ?between traditional publishing and the new, less authoritative POD channels.

Obviously, this presents a major challenge to other on-demand services like iUniverse, Xlibris and Lulu. It will be interesting to observe how the publishing cultures on these sites will differ. Lulu.com seems to hold the most potential for the emergence of a new ecosystem of independent imprints and publishing storefronts, with the Lulu brand receding into a more infrastructural role. iUniverse and Xlibris still feel more like good old-fashioned vanity presses. Amazon theoretically offers good exposure for self-published authors, but again, as I queried above w/r/t social filtering, will CreateSpace titles be ghetto-ized in an Amazon sub-space or fully integrated into the world of books?

blooker nominees

The short list of nominees for Lulu.com’s second annual Blooker Prize, which is given to the year’s best book adapted from or based on a blog (or web comic), has been announced. This piece in the UK Times looks at how some publishers have begun more aggressively talent scouting in the blogosphere.

physical books and networks 2

Much of our time here is devoted to the extreme electronic edge of change in the arena of publishing, authorship and reading. For some, it’s a more distant future than they are interested in, or comfortable, discussing. But the economics and means/modes of production of print are being no less profoundly affected — today — by digital technologies and networks.

The Times has an article today surveying the landscape of print-on-demand publishing, which is currently experiencing a boom unleashed by advances in digital technologies and online commerce. To me, Lulu is by far the most interesting case: a site that blends Amazon’s socially networked retail formula with a do-it-yourself media production service (it also sponsors an annual “Blooker” prize for blog-derived books). Send Lulu your book as a PDF and they’ll produce a bound print version, in black-and-white or color. The quality isn’t superb, but it’s cheap, and light years ahead of where print-on-demand was just a few years back. The Times piece mentions Lulu, but focuses primarily on a company called Blurb, which lets you design books with customized software called BookSmart, which you can download free from their website. BookSmart is an easy-to-learn, template-based assembly tool that allows authors to assemble graphics and text without the skills it takes to master professional-grade programs like InDesign or Quark. Blurb books appear to be of higher quality than Lulu’s, and correspondingly, more expensive.

Reading this reminded me of an email I received about a month back in response to my “Physical Books and Networks” post, which looked at authors who straddle the print and digital worlds. It came from Abe Burmeister, a New York-based designer, writer and artist, who maintains an interesting blog at Abstract Dynamics, and has also written a book called Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics. Actually, Burmeister is still in the midst of writing the book — but that hasn’t stopped him from publishing it. He’s interested in process-oriented approaches to writing, and in situating acts of authorship within the feedback loops of a networked readership. At the same time, he’s not ready to let go of the “objectness” of paper books, which he still feels is vital. So he’s adopted a dynamic publishing strategy that gives him both, producing what he calls a “public draft,” and using Lulu to continually post new printable versions of his book as they are completed.

Reading this reminded me of an email I received about a month back in response to my “Physical Books and Networks” post, which looked at authors who straddle the print and digital worlds. It came from Abe Burmeister, a New York-based designer, writer and artist, who maintains an interesting blog at Abstract Dynamics, and has also written a book called Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics. Actually, Burmeister is still in the midst of writing the book — but that hasn’t stopped him from publishing it. He’s interested in process-oriented approaches to writing, and in situating acts of authorship within the feedback loops of a networked readership. At the same time, he’s not ready to let go of the “objectness” of paper books, which he still feels is vital. So he’s adopted a dynamic publishing strategy that gives him both, producing what he calls a “public draft,” and using Lulu to continually post new printable versions of his book as they are completed.

His letter was quite interesting so I’m reproducing most of it:

Using print on demand technology like lulu.com allows for producing printed books that are continuously being updated and transformed. I’ve been using this fact to develop a writing process loosely based upon the linux “release early and release often” model. Books that essentially give the readers a chance to become editors and authors a chance to escape the frozen product nature of traditional publishing. It’s not quite as radical an innovation as some of your digital and networked book efforts, but as someone who believes there always be a particular place for paper I believe it points towards a subtly important shift in how the books of the future will be generated.

…one of the things that excites me about print on demand technology is the possibilities it opens up for continuously evolving books. Since most print on demand systems are pdf powered, and pdfs have a degree of programability it’s at least theoretically possible to create a generative book; a book coded in such a way that each time it is printed an new result comes out. On a more direct level though it’s also very practically possible for an author to just update their pdf’s every day, allowing for say a photo book to contain images that cycle daily, or the author’s photo to be a web cam shot of them that morning.

When I started thinking about the public drafting process one of the issues was how to deal with the fact that someone might by the book and then miss out on the content included in the edition that came out the next day. Before I received my first hard copies I contemplated various ways of issuing updated chapters and ways to decide what might be free and what should cost money. But as soon as I got that hard copy the solution became quite clear, and I was instantly converted into the Cory Doctrow/Yochai Benkler model of selling the book and giving away the pdf. A book quite simply has a power as an object or artifact that goes completely beyond it’s content. Giving away the content for free might reduce books sales a bit (I for instance have never bought any of Doctrow’s books, but did read them digitally), but the value and demand for the physical object will still remain (and I did buy a copy of Benkler’s tome.) By giving away the pdf, it’s always possible to be on top of the content, yet still appreciate the physical editions, and that’s the model I have adopted.

And an interesting model it is too: a networked book in print. Since he wrote this, however, Burmeister has closed the draft cycle and is embarking on a total rewrite, which presumably will become a public draft at some later date.

lulu.tv testing some boundaries of copyright

Lulu.tv made recent news with their new video sharing service which has a unique business model. Bob Young the head of Lulu.tv and founder of the self publishing service Lulu.com also founded Red Hat, which commercially sells open source software. He has been doing interesting experiments in creating business that harness the creative efforts of people.

Lulu.tv made recent news with their new video sharing service which has a unique business model. Bob Young the head of Lulu.tv and founder of the self publishing service Lulu.com also founded Red Hat, which commercially sells open source software. He has been doing interesting experiments in creating business that harness the creative efforts of people.

The new revenue sharing strategy behind Lulu.tv is fairly simple. Anyone can post or view content for free, as with Google Video or YouTube. However, it offers a “pro” version, which charges users to post video. 80% of the fees paid by goes to an account and the money is distributed each month based on the number of unique downloads to subscribing members.

This strategy has a similar tone to the ideas of Terry Fisher who has been promoting and the related idea of an alternative media cooperative model. In Fisher’s model, viewers (rather than the content creators) pay a media fee to view content and the collected revenues are redistributed to the creators in the cooperative. Lulu.tv makes logical adjustments to the Fisher model because other video sharing services are already offering their content for free. Because there are a lot more viewers of these sites than posters, the potential revenue has limited growth. However, I can imagine if the economic incentive becomes great enough, then the best content could gravitate to Lulu.tv and they could potentially charge viewers for that content. Alternatively, revenue from paid advertising could be added the pool of funds for “pro” users.

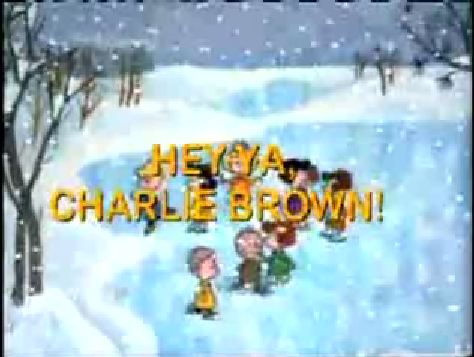

Introducing money into environments also produces friction and video sharing will be no different. Moving content from a free service to a pay service will increase copyright concerns, which have yet to be discussed. People tend to post “other people’s content” on YouTube and GoogleVideo, which often contains copyrighted material. For example, Hey Ya, Charlie Brown scores a Charlie Brown Christmas Special with Outkast’s hit single. It is not clear if this video was posted by a pro user, or who made the video and if any rights were cleared. Although, for instance, YouTube takes down content when asked to by copyright holders, many holders do not complain because that media (for instance 80s music videos) have limited or no replay value. With video remixes, creators have traditionally given away their work and allow it to be shared because there was no or little earning potential for the remixes. However with Lulu.tv’s model, this media is suddenly able to generate money. Remixers who have traditionally allows the viral distribution of their work, now they have an economic incentive to host their content in one specific location and hence control the distrbution of the work (sound familiar?)

Introducing money into environments also produces friction and video sharing will be no different. Moving content from a free service to a pay service will increase copyright concerns, which have yet to be discussed. People tend to post “other people’s content” on YouTube and GoogleVideo, which often contains copyrighted material. For example, Hey Ya, Charlie Brown scores a Charlie Brown Christmas Special with Outkast’s hit single. It is not clear if this video was posted by a pro user, or who made the video and if any rights were cleared. Although, for instance, YouTube takes down content when asked to by copyright holders, many holders do not complain because that media (for instance 80s music videos) have limited or no replay value. With video remixes, creators have traditionally given away their work and allow it to be shared because there was no or little earning potential for the remixes. However with Lulu.tv’s model, this media is suddenly able to generate money. Remixers who have traditionally allows the viral distribution of their work, now they have an economic incentive to host their content in one specific location and hence control the distrbution of the work (sound familiar?)

I’m quite glad that Lulu.tv is experimenting in this vein. If it succeeds, the end effect will push the once fringe media and distribution even deeper into the mainstream. For people concerned with overreaching copyright protection, this could be also be disastrous depending on how we as a culture decide to accept it. The copyright holders could use Lulu.tv has a further argument for yet stronger protections to intellectual property. On the other hand, it could mainstream the idea that remixing is a transformative use. The tensions between media producers, copyright holders, distributors and viewers continue to be evolve and are important to document and note as they move forward.

on ebay: collaborative fiction, one page at a time

Phil McArthur is not a writer. But while recovering from a recent fight with cancer, he began to dream about producing a novel. Sci-fi or horror most likely — the kind of stuff he enjoys to read. But what if he could write it socially? That is, with other people? What if he could send the book spinning like a top and just watch it go?

Say he pens the first page of what will eventually become a 250-page thriller and then passes the baton to a stranger. That person goes on to write the second page, then passes it on again to a third author. And a fourth. A fifth. And so on. One page per day, all the way to 250. By that point it’s 2007 and they can publish the whole thing on Lulu.

The fruit of these musings is (or will be… or is steadily becoming) “Novel Twists”, a ongoing collaborative fiction experiment where you, I or anyone can contribute a page. The only stipulations are that entries are between 250 and 450 words, are kept reasonably clean, and that you refrain from killing the protagonist, Andy Amaratha — at least at this early stage, when only 17 pages have been completed. Writers also get a little 100-word notepad beneath their page to provide a biographical sketch and author’s notes. Once they’ve published their slice, the subsequent page is auctioned on Ebay. Before too long, a final bid is accepted and the next appointed author has 24 hours to complete his or her page.

Networked vanity publishing, you might say. And it is. But McArthur clearly isn’t in it for the money: bids are made by the penny, and all proceeds go to a cancer charity. The Ebay part is intended more to boost the project’s visibility (an article in yesterday’s Guardian also helps), and “to allow everyone a fair chance at the next page.” The main point is to have fun, and to test the hunch that relay-race writing might yield good fiction. In the end, McArthur seems not to care whether it does or not, he just wants to see if the thing actually can get written.

Surrealists explored this territory in the 1920s with the “exquisite corpse,” a game in which images and texts are assembled collaboratively, with knowledge of previous entries deliberately obscured. This made its way into all sorts of games we played when we were young and books that we read (I remember that book of three-panel figures where heads, midriffs and legs could be endlessly recombined to form hilarious, fantastical creatures). The internet lends itself particularly well to this kind of playful medley.

questions on libraries, books and more

Last week, Vince Mallardi contacted me to get some commentary for a program he is developing for the Library Binding Institute in May. I suggested that he send me some questions, and I would take a pass at them, and post them on the blog. My hope that is, Vince, as well as our colleagues and readers will comment upon my admittedly rough thoughts I have sketched out, in response to his rather interesting questions.

1. What is your vision of the library of the future if there will be libraries?

Needless to say, I love libraries, and have been an avid user of both academic and public libraries since the time I could read. Libraries will be in existence for a long time. If one looks at the various missions of a library, including the archiving, categorization, and sharing of information, these themes will only be more relevant in the digital age for both print and digital text. There is text whose meaning is fundamentally tied to its medium. Therefore, the creation and thus preservation of physical books (and not just its digitization) is still important. Of course, libraries will look and function in a very different way from how we conceptualize libraries today.

As much as, I love walking through library stacks, I realize that it is a luxury of the North, which was made more clear to me at the recent Access to Knowledge conference my colleague and I were fortunate enough to attend. In the economic global divide of the North and South, the importance of access to knowledge supersedes my affinity for paper books. I realize that in the South, digital libraries are a much efficient use of resources to promote sustainable knowledge, and hopefully economic, growth.

2. How much will self-publishing benefit book manufacturers, indeed save them?

Recently, I have been very intrigued with the notion of Print On Demand (POD) of books. My hope is that the stigma will be removed from the so-called “vanity press.” Start-up ventures, such as LuLu.com, have the potential to allow voices to flourish, where in the past they lacked access to traditional book publishing and manufacturing.

Looking at the often cited observation that 57% of Amazon book sales comes from books in the Long Tail (here defined as the catalogue not typically available in the 100,000 books found in a B&N superstore,) I wonder if the same economic effect could be reaped in the publishing side of books. Increasing efficiency of digital production, communication, and storage, relieve economic pressures of the small run printing of books. With print on demand, costs such as maintaining inventory are removed, as well, the risk involved in estimating the demand for first runs is reduced. Similarly, as I stated in my first response, the landscape of book manufacturing will have to adapt as well. However, I do see potential for the creation of more books rather than less.

3. What co-existence do you foresee between the printed and electronic book, as co-packaged, interactive via barcodes or steganography? etc.

Paper based books will still have its role in communication in the future. Paper is still a great technology for communication. For centuries, paper and books were the dominate medium because that was the best technology available. However, with film, television, radio and now digital forms, it is not longer always true. Thus the use of print text must be based upon the decision by the author that paper is the best medium for her creative purposes. Moving books into the digital allows for forms that cannot exist as a paper book, for instance the inclusion of audio and video. I can easily see a time when an extended analysis of a Hitchcock movie will be an annotated movie, with voice over commentary, text annotation and visual overlays. These features cannot be reproduced in traditional paper books.

Rather, that try to predict specific applications, products or outcomes, I would prefer to open the discussion to a question of form. There is fertile ground to explore the relationship between paper and digital books, however it is too early for me to state exactly what that will entail. I look forward to seeing what creative interplay of print text and digital text authors will produce in the future. The co-existence between the print and electronic book in a co-packaged form will only be useful and relevant, if the author consciously writes and designs her work to require both forms. Creating a pdf of Proust’s Swann Way’s is not going to replace the print version. Likewise, printing out Moulthrop’s Victory Garden do not make sense either.

4. Can there be literacy without print? To the McLuhan Gutenberg Galaxy proposition.

Print will not fade out of existence, so the question is a theoretical one. Although, I’m not an expert in McLuhan, I feel that literacy will still be as vital in the digital age as it is today, if not more so. The difference between the pre-movable type age and the electronic age, is that we will still have the advantages of mass reproduction and storage that people did not have in an oral culture. In fact, because the marginal cost of digital reproduction is basically zero, the amount of information we will be subjected to will only increase. This massive amount of information which we will need to process and understand will only heighten the need for not only literacy, but media literacy as well.