is the slogan of Mojiti, a company based in Beijing which has enabled commenting for video. Users can annotate any video on YouTube, Google, MySpace and about twenty other providers with text, shape and images. the annotations can be animated as well. The interface for making comments is unusually simple and straightforward. On first glance this is an important step forward in web 2.0 applications. [note: the demos all show text fields with solid backgrounds obscuring the video. in fact it’s quite easy to make the text box transparent or to turn off the annotations at any point to see the unalloyed video]

Category Archives: video

the power of collaboration and remix culture — the exquisite corpse goes video

Yet one more reason to check in to Alex Itin’s remarkable blog if you haven’t recently or ever. As you may have read here several weeks ago, alex started a group on Flickr, The Library Project, for people to post works that have been created by two or more artists, building serially on each other’s efforts. Last October Alex posted a beautiful video he made as an homage to the mystical Alpine light know as die alpen lumen. In a nod to the exquisite corpse form of The Library Project, a Japanese artist, Eat A Bug, posted a film he made in response. Serious kudos to alex and all his fellow artists who are demonstrating the power of collaboration and remix culture.

dutch fund audiovisual heritage to the tune of 173 million euros

Larry Lessig writes in Free Culture:

Why is it that the part of our culture that is recorded in newspapers remains perpetually accessible, while the part that is recorded on videotape is not? How is it that we’ve created a world where researchers trying to understand the effect of media on nineteenth-century America will have an easier time than researchers trying to understand the effect of media on twentieth-century America?

Twentieth century Holland, it turns out, will be easier to decipher:

The Netherlands Government announced in its annual budget proposal the support for the project “Images for the Future” (in Dutch). Images for the Future is a large-scale conservation and digitalisation operation comprising 285,000 hours of film, television and radio recordings, and 2.9 million photos. The investment of 173 million euro, is spread over a period of seven years.

…It is unprecedented in its scale and ambition. All these films, programmes and photos will be made available for educational and creative purposes. An infrastructure for digital distribution will also be developed. A basic collection will be made available without copyright or under a Creative Commons licence. Making this heritage digitally available will lead to innovative applications in the area of new media and the development of valuable services for the public. The income/expense analysis included in the project plan shows that on balance the project will produce a positive social effect in the Dutch economy to the value of 20 to 60 million euros.

— from Association of Moving Image Archivists list-server

Pretty inspiring stuff.

Eddie Izzard once described the Netherlandish brand of enlightenment in a nutshell: “The Dutch speak four languages and smoke marijuana!” We now see that they also deem it wise policy to support a comprehensive cultural infrastructure for the 21st century, enabling their citizens to read, quote and reuse the media that shapes their world (while they whiz around on bicycles over tidy networks of canals). Not so here in the States where the government works for the monopolies, keeping big media on the dole through Sonny Bono-style protectionism. We should pass our benighted politicos a little of what the Dutch are smoking.

the library project: a networked art experiment

Digital collaboration with me-jade, dou_ble_you and others in the Flickr Library Project

As he recently reflected upon here, Alex Itin has long been working at the border zones of art forms, moving in recent years to the strange intersection of paint and pixels. His blog is one of the most wildly inventive uses of that form, combining blazing low-res images of his paintings with text, photographs, short films, animated GIFs and audio mashups. All of this is done within the constraints of the blog’s scroll-like form — a constraint which Alex embraces, even relishes. I sometimes imagine the scroll endlessly emitting from Alex’s head like tape from a cash register, a continuous record of his transactions with the world.

ITIN place has been on the web for nearly two years now. In his second year, Alex began to explore new avenues out of the blog, establishing a presence on social media sites like Flickr, YouTube, Vimeo (a classier YouTube) and MySpace. Through these networked rovings, Alex has found a larger audience for his work, attracting new “readers” back to the blog where the various transmitted videos and images are reassembled in the scroll. He’s also established relationships with a number of other artists making interesting use of the web, particularly on Flickr and Vimeo. Recently, Alex invited a number of folks from the Flickr community to participate in a collaborative art project — a kind of exquisite corpse game via post. Here’s Alex:

The idea is that one artist takes a hardcover from a book, tears out the pages and draws in one half (or half draws in both halves) of the binder/diptyque. In a nod to Ray Johnson, the two books are mailed (swapped) and Each of these will be finished by the other. The results are posted in a Flicker group called (what else) The Library Project. From this group, hopefully a show will be curated for New York, or Paris, or Basel, or Berlin, or wherever anyone wants to show this project. It should be deliciously portable… get working…get collaborating…get reading!

As of this writing, the Library has racked up 278 members and has 205 images in its pool. A few of these are collaborations that have already made their trek across land, sea and air, others are purely digital combinations, while still others are simply book-inspired works submitted in the spirit of the project.

Alex has been documenting the process on his blog, weaving in some of the images. Styles combine, narratives emerge. In one video (excerpted here) he films himself receiving his first half-completed book from a Canadian artist known as driftwould. He unpacks the drawings and lets out a “wow,” than a sort of humbled sigh. It’s a nice moment of return to the physical world after several years of probing the digital ether.

And here’s how that turned out:

Read Alex’s documentation here and here.

Stay tuned for more — the project has only just begun. Plus, we’ve begun designing a fantastic new interface for Alex’s blog archives, which we’ll talk more about soon.

plato’s cave

HiddenHistory on Vimeo

Ben’s post last week on the darker side of flash shone like a light bulb. I’d spent the morning manipulating a scanned image of Ditr Roth, by taking this video clip from Vimeo and downloading the source quicktime (which Vimeo allows you to do) importing that into i-movie and exporting thirteen still images as jpegs to sequence into an animated gif. Then I started pulling wav. files off cds and layering tracks and looping them and turning them into mpegs. In other words, it was a day like any other, but when I read Social Powerpoint, I considered how many little media format borders I’d just crossed and how many times I cross those borders on any given day in any given post and how much I take that freedom for granted. So, is flash like that damn wall they keep threatening to build in Texas, or built once in Germany and before that in China (and as a bird, or a bowerbird knows….walls never really work if you can fly over them, or go around)?

I don’t know enough about flash coding, but I worry that these walls are all already there in the very way that people read different media. In the way that their eyeballs see them and their earballs hear them. A photograph and a drawing will both appear on a digital page as jpegs, but it still seems a little tricky to get people to look at them in relation to each other. In painting, you take two paintings and put them side by side: BANG, you have a diptych. It becomes a third thing. I thought that logic would translate very easily to a still image and a moving one, or a sound and word, but It seems that people like compartments. They like to have their still photos at flickr and their video on You tube and their music on i-tunes, and their book on tape as a podcast, etc. If things appear on a digital page together, they are meant to be surrounded by a trompe l’oeil metallic players just so that there’s no aesthetic miscegenation going on. It’s what we’re used to.

I tend to use a bunch of media sharing services for IT IN place both as a way to host media and as a way of advertising. One of the realities I’ve come to deal with is that many more people are going to see my work as discrete media objects on flickr and vimeo than will ever make it to the blog to read these things together in the way that I intended. People seem to get something out of the picutres and the videos as pictures and videos, etc., but I always feel they are missing half the point. I think of it as reading sentence fragments, or stanzas and never seeing the whole poem.

At this point, each media is like a different language and trying to put them all together into a single whole is a Wasteland exercise… and the wasteland is patrolled by Minutemen and snakes.

Maybe, in some ways throwing these fragments out into the digital desert is part of the poetry. Maybe the networked landscape offers the thrill of archeology for the reader, like digging up little photo, sound, and video tiles that lead the reader on to find the mosaic. Today someone left a comment on flickr:

“your pieces are like secret boxes.. when i click the link it’s like lifting a lid and inside there is always something surprisingly ‘other’ and beautiful..”

….I could tack a hundred paintings on a hundred walls and never get a such a nice sentence in return.

But then there is the voice of my mother and also the significant other saying, “So how do you make money?”

It’s important to point out that for me the nexus of meaning is in mark making (wether as writing, or drawing which I think are intimately and evolutionarily (?) cave connected). My practice always revolves around drawing… All the different media I use are like a series of mirrors that multiply all the possible ways to see and understand things, but as an art animal, my primary way of knowing where I stand in the funhouse is to make a mark and so I think my practice revolves around the drawings… they are the map, if you will. While not exactly having any sort of business model, I always figured digital media would lead people to want to see and maybe own the “original” drawings and paintings. Of course, I thought of it this way, because that’s just what people traditionally have done: they sell things to people who collect things. It’s what we’re used to.

Maybe the past few months of deciphering fluxus history (and it’s anti-art leanings) has put the zap on my head, but lately I’m a bit lost in a Labyrinth of my own creation. The blog has sort of become the work of art and none of it’s discrete parts (read media) are more or less important…not when I’m successful in a post. It may be Greek and Latin and French and German and English and Japanese, but it has to be read together if you want to get the jokes. I don’t know… maybe I’m speaking in tongues. I have a feeling the youtube generation will be malf blahming flah wast di blamspoontoop dang glover….

* addendum: as I wrote this, three people on flickr enquired about buying work.

– my Flickr page

– my Vimeo page

an excursion into old media

![]()

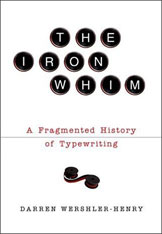

Last summer on a trip to Canada I picked up a copy of Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: a Fragmented History of Typewriting. It’s a look at our relationship with one particular piece of technology through a compound eye, investigating why so many books striving to be “literary” have typewriter keys on the cover, novelists’ feelings for their typewriters, and the complicated relationship between typewriter making and gunsmithing, among a great many other things. The book ends too soon, as Wershler-Henry doesn’t extend his thinking about typewriters and writing into broader conclusions about how technology affects writing (for that see Hugh Kenner’s The Mechanic Muse) but it’s still worth tracking down.

Last summer on a trip to Canada I picked up a copy of Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: a Fragmented History of Typewriting. It’s a look at our relationship with one particular piece of technology through a compound eye, investigating why so many books striving to be “literary” have typewriter keys on the cover, novelists’ feelings for their typewriters, and the complicated relationship between typewriter making and gunsmithing, among a great many other things. The book ends too soon, as Wershler-Henry doesn’t extend his thinking about typewriters and writing into broader conclusions about how technology affects writing (for that see Hugh Kenner’s The Mechanic Muse) but it’s still worth tracking down.

It did start me thinking about my use of technology. Back in junior high I was taught to type on hulking IBM Selectrics, but the last time I’d used a typewriter was to type up my college application essays. (This demonstrates my age: my baby brother’s interactions with typewriters have been limited to once finding the family typewriter in the basement; though he played with it, he says that he “never really produced anything of note on it,” and he found my query about whether or not he’d typed his college essays so ridiculous as not to merit reply.) Had I been missing out? A little investigation revealed a thriving typewriter market on eBay; for $20 (plus shipping & handling) I bought myself a Hermes Baby Featherweight. With a new ribbon and some oiling it works well, though it’s probably from the 1930s.

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a Numark PT-01) and cheap. It’s also because much of the music I’ve been listening to lately doesn’t get released on CD: dance music is still mostly vinyl-based, though it’s made the jump to MP3s without much trouble. There wasn’t much reasoning past that: after buying my record player I started buying records, almost all things I’d previously heard as MP3s. And, of course, I’d never owned a record player and I was curious what it would be like.

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a Numark PT-01) and cheap. It’s also because much of the music I’ve been listening to lately doesn’t get released on CD: dance music is still mostly vinyl-based, though it’s made the jump to MP3s without much trouble. There wasn’t much reasoning past that: after buying my record player I started buying records, almost all things I’d previously heard as MP3s. And, of course, I’d never owned a record player and I was curious what it would be like.

![]()

So what happened when I started using this technology of an older generation? The first thing you notice about using a typewriter (and I’m specifically talking about using a non-electric typewriter) is how much sense it makes. When my typewriter arrived, it was filthy. I scrubbed the gunk off the top, then unscrewed the bottom of it to get at the gunk inside it. Inside, typewriters turn out to be simple machines. A key is a lever that triggers the hammer with the key on it. The energy from my action of pressing the key makes the hammer hit the paper. There are some other mechanisms in there to move the carriage and so on, but that’s basically it.

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise: this guy has made a record player out of paper. If you look at the record, you can see from the grooves where the tracks begin and end; quiet passages don’t look the same as loud passages. You don’t get any such information from a CD: a burned CD looks different depending on how much information it has on it, but the bottom from every CD from the store looks completely identical. Without a label, you can’t tell whether a disc is an audio CD, a CD-ROM, or a DVD.

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise: this guy has made a record player out of paper. If you look at the record, you can see from the grooves where the tracks begin and end; quiet passages don’t look the same as loud passages. You don’t get any such information from a CD: a burned CD looks different depending on how much information it has on it, but the bottom from every CD from the store looks completely identical. Without a label, you can’t tell whether a disc is an audio CD, a CD-ROM, or a DVD.

![]()

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

What my excursion into old technology makes me notice is how comparatively opaque our current technology is. It’s not hard to figure out how a typewriter works: were a monkey to decide that she wanted to write Hamlet, she could figure out how to use a typewriter without any problem. (Though I’m sure it exists, I couldn’t dig up any footage on YouTube of a monkey using a record player. This cat operating a record player bodes well for them, though.) It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for even a monkey and a cat working together to figure out how to use a laptop to do the same thing.

What my excursion into old technology makes me notice is how comparatively opaque our current technology is. It’s not hard to figure out how a typewriter works: were a monkey to decide that she wanted to write Hamlet, she could figure out how to use a typewriter without any problem. (Though I’m sure it exists, I couldn’t dig up any footage on YouTube of a monkey using a record player. This cat operating a record player bodes well for them, though.) It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for even a monkey and a cat working together to figure out how to use a laptop to do the same thing.

Obviously, designing technologies for monkeys is a foolish idea. Computers are useful because they’re abstract. I can do things with it that the makers of my Hermes Baby Featherweight couldn’t begin to imagine in 1936 (although I am quite certain than my MacBook Pro won’t be functional in seventy years). It does give me pause, however, to realize that I have no real idea at all what’s happening between when I press the A key and when an A appears on my screen. In a certain sense, the workings of my computer are closed to me.

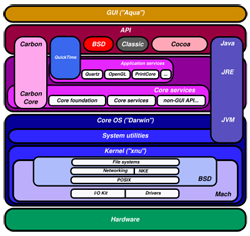

![]()

Let me add some nuance to a previous statement: not only are computers abstract, they have layers of abstraction in them. Somewhere deep inside my computer there is Unix, then on top of that there’s my operating system, then on top of that there’s Microsoft Word, and then there’s the paper I’m trying to write. (It’s more complicated than this, I know, but allow me this simplification for argument’s sake.) But these layers of abstraction are tremendously useful for the users of a computer: you don’t have to know what Unix or an operating system is to write a paper in Microsoft Word, you just need to know how to use Word. It doesn’t matter whether you’re using a Mac or a PC.

The world wide web takes this structure of abstraction layers even further. With the internet, it doesn’t matter which computer you’re on as long as you have an internet connection and a web browser. Thus I can go to another country and sit down at an internet café and check my email, which is pretty fantastic.

And yet there are still problems. Though everyone can use the Internet, it’s imperfect. The same webpage will almost certainly look different on different browsers and on different computers. This is annoying if you’re making a web page. Here at the Institute, we’ve spent ridiculous amounts of time trying to ascertain that video will play on different computers and in different web browsers, or wondering whether websites will work for people who have small screens.

A solution that pops up more and more often is Flash. Flash content works on any computer that has the Flash browser plugin, which most people have. Flash content looks exactly the same on every computer. As Ben noted yesterday, Flash video made YouTube possible, and now we can all watch videos of cats using record players.

But there’s something that nags about Flash, the same thing that bothers Ben about Flash, and in my head it’s consonant with what I notice about computers after using a typewriter or a record player. Flash is opaque. Somebody makes the Flash & you open the file on your computer, but there’s no way to figure out exactly how it works. The View Source command in your web browser will show you the relatively simple HTML that makes up this blog entry; should you be so inclined, you could figure out exactly how it worked. You could take this entry and replace all the pictures with ones that you prefer, or you could run the text through a faux-Cockney filter to make it sound even more ridiculous than it does. You can’t do the same thing with Flash: once something’s in Flash, it’s in Flash.

A couple years ago, Neal Stephenson wrote an essay called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” which looked at why it made a difference whether you had an open or closed operating system. It’s a bit out of date by now, as Stephenson has admitted: while the debate is the same, the terms have changed. It doesn’t really matter which operating system you use when more and more of our work is being done on web applications. The question of whether we use open or closed systems is still important: maybe it’s important to more of us, now that it’s about how we store our text, our images, our audio, our video.

A couple years ago, Neal Stephenson wrote an essay called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” which looked at why it made a difference whether you had an open or closed operating system. It’s a bit out of date by now, as Stephenson has admitted: while the debate is the same, the terms have changed. It doesn’t really matter which operating system you use when more and more of our work is being done on web applications. The question of whether we use open or closed systems is still important: maybe it’s important to more of us, now that it’s about how we store our text, our images, our audio, our video.

social powerpointing, or, the darker side of flash

SlideShare is a new web application that lets you upload PowerPoint (.ppt and .pps) or OpenOffice (.odp) slideshows to the web for people to use and share. The site (which is in an invite-only beta right now, though accounts are granted within minutes of a request) feels a lot like the now-merged Google Video and YouTube. Slideshows come up with a unique url, copy-and-paste embed code for bloggers, tags, a comment stream and links to related shows. Clicking a “full” button on the viewer controls enlarges the slideshow to fill up most of the screen. Here’s one I found humorously diagramming soccer strategies from various national teams:

Another resemblance to Google Video and YouTube: SlideShare rides the tidal wave of Flash-based applications that has swept through the web over the past few years. By achieving near-ubiquity with its plugin, Flash has become the gel capsule that makes rich media content easy to swallow across platform and browser (there’s a reason that the web video explosion happened when it did, the way it did). But in a sneaky way, this has changed the nature of our web browsers, transforming them into something that more resembles a highly customizable TV set. And by this I mean to point out that Flash inhibits the creative reuse of the materials being delivered since Flash-wrapped video (or slideshows) can’t, to my knowledge, be easily broken apart and remixed.

Where once the “view source” ethic of web browsers reigned, allowing you to retrieve the underlying html code of any page and repurpose all or parts of it on your own site, the web is becoming a network of congealed packages — bite-sized broadcast units that, while nearly effortless to disseminate through linking and embedding, are much less easily reworked or repurposed (unless the source files are made available). The proliferation of rich media and dynamic interfaces across the web is no doubt exciting, but it’s worth considering this darker side.

mckenzie wark interview in halo

This interview with McKenzie Wark was conducted inside an online version of the Halo 2 video game as part of the upcoming fourth episode of This Spartan Life, “a talk show in gamespace.” Many thanks to Chris Burke and the TSL team for doing such a fantastic job. Click the image to play (it’s a little under 14 minutes):

From the interview, here’s McKenzie on collaborating with readers inside his book:

“It sort of brings out what writing always is anyway, which is that, in a sense, you’re always the DJ of other people’s thoughts and ideas, and this just makes that manifest.”

Also see this interesting thread in the GAM3R 7H30RY forum from a while back — a discussion between McKenzie and Chris about “glitching” and other forms of trifling or hacking within the game (the bread and butter of machinima filmmakers), and whether this can lead to real freedom. There’s a moment later on in the video where the debate gets wonderfully concretized in the physical landscape of the game world.

We “shot” the footage back in August at Chris’s studio in Brooklyn. I managed to snap a couple of hazy pictures with my camera phone:

On the left you see the room where Chris and the two camera operators have their consoles. On the right is McKenzie in his own little cave. Everything is recorded through video feeds running out of the Xboxes. Ken and Chris talk over headsets and move around the game environment while the two “cameras” follow behind (the cameras are just the perspectives of the other two gamers). The chaos during Ken’s reading at the end is the work of other online gamers from around the country — TSL groupies who like helping out with shoots and generally raising hell. Seeing Chris try to coordinate this rambunctious crew long distance was highly entertaining.

(If you haven’t seen it, also check out This Spartan Life’s interview with Bob from their first episode. A real treat.)

“i photograph to remember” moves to the ipod

Pedro Meyer, founder of ZoneZero, the pioneering photography site, just wrote to say that he’s working on an Ipod version of I Photograph to Remember, the cdrom he made in the early 90s. It’s a deeply moving portrait documenting the last years of his parents’ life. Pedro invites readers of if:book to download a beta version HERE. He’s hoping for feedback so please send comments.

I thought it might be interesting to describe the debut of IPTR at the Digital World Conference in Beverly Hills in 1991. To appreciate this you have to understand that at that time no one had ever really seen anything on a computer screen with emotional content. The audience consisted of hyperactive, mostly male, senior executives who normally couldn’t sit still or be quiet for five minutes. But for thirty-two minutes, from the moment the lights went down till the closing credits, there wasn’t even the sound of breathing. People were literally stunned as they suddenly realized that the number-crunching, text processing machine on their desk could convey complex, profound feelings.

book trailers, but no network

We often conceive of the network as a way to share culture without going through the traditional corporate media entities. The topology of the network is created out of the endpoints; that is where the value lies. This story in the NY Times prompted me to wonder: how long will it take media companies to see the value of the network?

The article describes a new marketing tool that publishers are putting into their marketing arsenal: the trailer. As in a movie trailer, or sometimes an informercial, or a DVD commentary track.

“The video formats vary as widely as the books being pitched. For well-known authors, the videos can be as wordy as they are visual. Bantam Dell, a unit of Random House, recently ran a series in which Dean Koontz told funny stories about the writing and editing process. And Scholastic has a video in the works for “Mommy?,” a pop-up book illustrated by Maurice Sendak that is set to reach stores in October. The video will feature Mr. Sendak against a background of the book’s pop-ups, discussing how he came up with his ideas for the book.”

Who can fault them for taking advantage of the Internet’s distribution capability? It’s cheap, and it reaches a vast audience, many of whom would never pick up the Book Review. In this day and age, it is one of the most cost effective methods of marketing to a wide audience. By changing the format of the ad from a straight marketing message to a more interesting video experience, the media companies hope to excite more attention for their new releases. “You won’t get young people to buy books by boring them to death with conventional ads,” said Jerome Kramer, editor in chief of The Book Standard.”

But I can’t help but notice that they are only working within the broadcast paradigm, where advertising, not interactivity, is still king. All of these forms (trailer, music video, infomercial) were designed for use with television; their appearance in the context of the Internet further reinforces the big media view of the ‘net as a one-way broadcast medium. A book is a naturally more interactive experience than watching a movie. Unconventional ads may bring more people to a product, but this approach ignores one of the primary values of reading. What if they took advantage of the network’s unique virtues? I don’t have the answers for this, but only an inkling that publishing companies would identify successes sooner and mitigate flops earlier, that the feedback from the public would benefit the bottom line, and that readers will be more engaged with the publishing industry. But the first step is recognizing that the network is more than a less expensive form of television.