In marked contrast to J K Rowling, whose battles against the publication of a fan-created Potter encyclopedia we’ve covered here, fantasy author Naomi Novik‘s website hosts a wiki in which fans of her writing help to co-create an encyclopedic guide to her Temeraire novels. It’s no coincidence that Novik is one of a handful of fanfic writers who’ve made the transition to publication as ‘original’ authors. She also chairs the Organization for Transformative Works, an archive dedicated to fanfic or ‘transformative’ work.

Novik’s approach reflects a growing recognition by many in the content industries that mass audience engagement with a given fictional world is can deliver benefits worth that outweigh any perceived losses due to copyright infringement by ‘derivative’ work. Echoing the tacit truce between the manga industry and its participatory fan culture (covered here last November), Novik’s explicit welcoming of fan participation in her fictional universes points towards a model of authorship that goes beyond a crude protectionism of the supposed privileged position of ‘author’ towards a recognition that, while creativity and participation are in some senses intrinsic to the read/write Web, not all creators are created equal – nor wish to be.

While a simplistic egalitarianism would propose that participatory media flatten all creative hierarchies, the reality is that many are content to engage with and develop a pre-existing fiction, and have no desire to originate such. Beyond recognising this fact, the challenge for post-Web2.0 writers is to evolve structures that reflect and support this relationship, without simply inscribing the originator/participator split as a cast-in-stone digital-era reworking of the author/reader dyad.

Category Archives: fiction

stories and places

I found this new site, 217babel.com set up by Brighton based journalist and writer William Shaw, to be a nice example of an online fiction that actually gets you reading rather than admiring it awhile and then glazing over or clicking away. A clean page, simple navigation and, most importantly, words that hook. Knock on the door and take a look.

Last year Shaw created another inspired piece: 41 Places, a city-wide artwork of 41 true stories, installed in the place where they happened – stories of people who live, work and play in Brighton, narrative non-fiction miniatures become something between a giant work of art, scattered through the city, and a treasure hunt of stories. The narratives were collected by Shaw between September 2006 and April 2007 and designed and installed by Richard Wölfstrome, John Easterby and Tom Snell.

on writing less

“Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parceque je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.” Pascal, Lettres provinciales, 16, Dec.14,1656.

I used to co-edit Pick Me Up, a cult London digital newsletter. After some years perfecting the flamboyant and self-congratulatory prose style that wins points as an Oxford undergrad, it was a whole new aesthetic. Minimal design, lots of white space. Keep the language plain, tell the story in simple words. We’d pass articles back and forth, ruthlessly prune one anothers’ words for anything too flash. I quickly stopped being precious about ‘my’ words: the aim was to make the language invisible.

Here’s my favorite ever Pick Me Up story.

Back then (we went our separate ways around 2 years ago), we were just-underground: our stories regularly hijacked by broadsheets and advertising campaigns. But since then the writing register I learned there has proliferated. It’s become the hip corporate copywriting style: Howies, Innocent Smoothies, any Web2.0 startup’s ‘About Us’ page.

Looking back, my involvement with Pick Me Up was the point where I started to think hard about the unique qualities of writing for the Web. But while plain language has become the bedrock of corporate communications, especially online, the ‘literary’ register resists its incursions. Wordsworth’s efforts notwithstanding, short sentences, plain language, and simple structure signify simple-mindedness. Discussing Japanese mobile phone fiction, Jane Sullivan writes in The Age

What’s the downside? Quality control, apparently. So far the mobile phone format has meant that the style of writing is generally unadventurous -? short, simple sentences, lots of dialogue, pauses to indicate thought -? and the stories themselves are hackneyed tales of romance.

I think it was Nietzsche who said that difficulty is often mistaken for greatness in a writer, because readers mistake their own pride at deciphering a text for an inherent profundity within it. Never mind that Pascal’s bon mot has been attributed to writers as long-gone and canonical as Cicero; forget brevity being the soul of wit; simplicity indicates poor quality.

Similarly. It’s become an article of faith in web design that any content below the fold (ie requiring a visitor to scroll down) will attract dramatically fewer viewings; this reflects a well-founded pragmatism oriented toward the need to hook a reader straight away. But few of the ‘literary’ webspaces I’ve come across in my research over the last few months pay much attention to this principle. I’ve lost count of the number of blog ‘novels’ I’ve come across, glanced through, bookmarked with every intention of returning for a closer read, and then forgotten. Part of the problem, again and again, is that I’m confronted with thousands of words of Arial ten-point and a scroll bar – along with the long sentences, elaborate structures and rich vocabulary that for many are the marker of literary quality. The net result is that these literary webspaces field a prose style and layout that – while it might make perfectly decent print reading – provides a sucky user experience.

My literacy credentials are more than respectable. I’m happy plowing my way through thorny texts – in the right form. But with billions of pages on the Web clamoring for attention, I get irritated with those that insist, however noble and literary their intentions, on making that most basic online error of loading too much text into one place. While the idea of savoring a sprawling, muscular Jamesian sentence in the wifi-free zone of the subway delights me, the idea of being asked to do so online fills me with horror.

Whatever you may think of the actual story, the first episode in Pengin’s WeTellStories experiment, The 21 Steps, suggests a growing recognition of the need to adapt storytelling modes online. It’s a decent balance of Web-native visualization and textual storytelling. The reader doesn’t have to deal with more than 20 or so words per click, 40-50 per ‘chapter’. The whole thing takes 5-10 minutes to read. This, in my view, is about where Web storytelling needs to be pitched.

Penguin’s production is an all-singing, all-dancing multimedia experince produced by an ARG studio. But simpler, text-based offerings are if anything more subject to the brutal need to edit for the Web reader’s attention span. Dickens’ chapter length was constrained in many cases by magazine serialization; now that DailyLit.com delivers daily bite-sized email or RSS doses of books to subscribers, will this affect the way future storytellers shape their work?

There is no disputing the fact that the Web is not the most comfortable medium for long-form reading (see Ian Bogost’s cracking article, and the ensuing discussion, for more on this). And the social media boom is spearheading a change in written language toward a simpler, plainer, more demotic register. So does this mean we are – over two centuries after Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads proposed a new literature embracing ‘the language of ordinary men’ – finally abandoning the privileging of prosiness as a marker of cultural quality? How does this square with the equation, so often taken for granted, between long-form writing and cultural virtue? Does it signify a cultural decline? Or is this just another kind of literacy, a new register for the emerging high priests of our evolving discourse to master and manipulate?

Either way, it’s hard to escape the fact that today we read, online, across multiple platforms including but not limited to a textual one. And yet, like a filmmaker grimly trying to observe the Aristotelian unities, many writers obstinately struggle to popularize material on the Web that is profoundly unsuited to being read there. I look forward to seeing more storytellers who embrace not only good writing but also the basic principles of good Web design – especially the one about not writing too much.

As a final note: I’m aware of the irony of my having just written a thousand words on brevity. My posts at if:book are the sole exception I make to general Web writing rule of 3 short paragraphs maximum; I have mixed feelings about making the exception. But for the sake of keeping it to a thousand I’ll save that discussion for another time.

this is a game. no really, it is

This morning, I received an envelope through the post. It contained two chapters of a pulp murder mystery, along with an invitation to a private gathering with the same title as the booklets: Looking For Headless. The gathering will take place in an anonymous City of London complex of rooms for hire by the hour.

It feels like the rabbit hole for a promising ARG. The accompanying letter describes how Georges Bataille formed a secret society, Acéphale, in 1938. Now, in 2008, two Swedish artists have discovered a Bahamas-based offshore company named Headless, which they have been investigating for the last year. At the meeting, I presume, I and the other invitees (whoever they are) will learn more.

A key characteristic of an ARG is the convention ‘This Is Not A Game’. Puppetmasters work to sustain the illusion that the game’s elements are part of the ‘real’ world – that’s a real person who emailed you, this is a real corporate website. Though players know the game is a game, there’s stil a thrill at the edges: should I phone that company, is it in-game, will I just get some confused receptionist? What’s real, who is complicit? But here the program is running backwards. Headless is, in fact, real. Owned by the Sovereign Trust Gibraltar. Little other information is available. Goldin+Senneby, the artist duo behind the project, state that they are interested in business as fiction, and in acts of withdrawal perpetrated through corporate structures.

ARG-like, the edge is ambiguous. The art-world jargon the artists use to discuss the project feels – perhaps deliberately – like yet another act of withdrawal. The two chapters of ‘Looking for Headless’ I received contain real transcripts of real detective reports, use the real names of real people, are authored by a real person – John Barlow . Though he has never met the people who commissioned him to work on this project, Barlow has scripted himself into the story. But parts of it are pure fiction. Reading the first two chapters of Looking for Headless is unnerving: which parts of this happened, and which did Barlow invent? In a story about the shadowy realm of offshore tax management, it is hard to be certain. Have the meeting’s invitees, as – it is implied – the reincarnation of Acéphale – Headless – been incorporated into a game, an art project, a work of fiction, or something altogether more sinister?

Today, Barlow left for Nassau, Bahamas to continue his investigation of Headless. He’ll be blogging his experiences here. It is not clear whether he will be blogging factual accounts, or embroidered ones. Or if, caught between pervasive, digitally-mediated self-narration and an emerging sphere of digital storytelling whose core insistence is that a game is not a game, we have lost the ability to tell the difference.

first of penguin’s interactive fictions up

Ben posted a few weeks back about an intriguing new interactive project in the pipeline from Penguin. WeTellStories, produced for Penguin by ARG studio SixToStart is now out in the open. Comprising six stories based on Penguin Classics, released one a week for the next six weeks, WeTellStories aims to create born-digital riffs on classic books.

I played through (‘read’ doesn’t quite describe it) the first of these earlier today: The 21 Steps by Charles Cumming, based on Buchan’s classic thriller The Thirty-Nine Steps. The 21 Steps is told through narrative bubbles that pop up as the story picks its way across a Google Earth-like satellite map, and describes the experience of a man suddenly caught up in sinister events that he can’t seem to escape.

Overall the experience works. The writing is spare enough to keep the pacing high, vital when the other umpteen billion pages I could possibly be surfing are all clamoring for my attention. The dot moving across the map creates a sense of movement forward (as well as some frustration as it crawls between narrative points), and the Google Earth styling is familiar enough as a reading environment for me to focus on enjoying the story rather than diverting too much energy to decoding peripheral material. The interface is simple and tactile in ways that advance the story without distracting from its development, either by offering diverging routes through it or overloading the central ‘chase’ narrative with multimedia clutter. And the satnav pictures add a pleasurable feeling of recognition (‘Look! There’s my house!’) to offset an essentially far-fetched story.

For a single-visit online story experience, it was nearly too long: I found myself checking how many instalments I still had to get through. The ending was somewhat anticlimactic. And though WeTellStories has been rumored to have ARG elements, and is produced by an ARG studio, I did a hunt around for potential ARG-style ‘further reading’ rabbit holes and found nothing. So either it’s too subtle for a journeywoman ARG fan like me, or the overarching ‘game’ element really is just the invitation to follow all six stories and then answer some questions to win a prize.

If so, I’ll be disappointed. But it’s early days still, and there may be more up SixToStart’s sleeve than I’ve seen so far. It’s encouraging to see ‘traditional’ publishers exploring inventive ways of riffing on their swollen backlists’ cachet and immeasurably rich narrative wealth. And The 21 Steps comes closer than most ‘authored’ digital fictions I’ve encountered to achieving some harmony between narrative and delivery mechanism. So though I’m being nitpicky, the project so far hints at the possiblity that we’re beginning to see online creative work that’s finding ways of marrying the Web’s fragmented, kinetic megalomania with the discipline needed for a gripping story.

flight paths 2.0

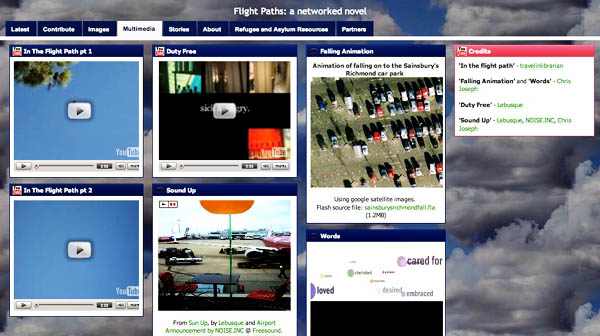

Back in December we announced the launch of Flight Paths, a “networked novel” that is currently being written by Kate Pullinger and Chris Joseph with feedback and contributions from readers. At that point, the Web presence for the project was a simple CommentPress blog where readers could post stories, images, multimedia and links, and weigh in on the drafting of terms and conditions for participation. Since then, Kate and Chris have been working on setting up a more flexible curatorial environment, and just this week they unveiled a lovely new Flight Paths site made in Netvibes.

Netvibes is a web-based application (still in beta) that allows you to build personalized start pages composed of widgets and modules which funnel in content from various data sources around the net (think My Yahoo! or iGoogle but with much more ability to customize). This is a great tool to try out for a project that is being composed partly out of threads and media fragments from around the Web. The blog is still embedded as a central element, and is still the primary place for reader-collaborators to contribute, but there are now several new galleries where reader-submitted works can be featured and explored. It’s a great new platform and an inventive solution to one of CommentPress’s present problems: that it’s good at gathering content but not terribly good at presenting it. Take a look, and please participate if you feel inspired.

Multimedia gallery on the new Flight Paths site

penguin of forking paths

Following on last year’s wiki novel, Penguin will soon launch another digital fiction experiment, this time focused on nonlinear storytelling. From Jeremy Ettinghausen on the Penguin blog:

…in a few weeks Penguin will be embarking on an experiment in storytelling (yes, another one, I hear you sigh). We’ve teamed up with some interesting folk and challenged some of our top authors to write brand new stories that take full advantage of the functionalities that the internet has to offer – this will be great writing, but writing in a form that would not have been possible 200, 20 or even 2 years ago. If you want to be alerted when this project launches sign up here – all will be revealed in March.

The “interesting folk” link goes to Unfiction, the main forum for the alternative reality gaming community. Intriguing…

art of compression: barry yourgrau’s keitai fictions

The Millions has an interesting interview with the South African-born, New York-resident writer Barry Yourgrau, who recently published a collection of “keitai” (cell phone) fiction in Japan. Known for bite-sized surrealist fables (as here), the hyper-compression of the cell phone display seemed like a natural challenge for Yourgrau, and he is now, to my knowledge, the first foreign writer to write successfully in Japan for the tiny screen. You can read a number of his keitai stories (which average about 350 words) on his blog, and hear him give a reading of the delightfully malevolent “Houndstooth,” which tells of a deadly fashion plague ravaging the Burberry-obsessed youth of Japan, on NPR.

Yourgrau believes that the popularity of keitai fiction in Japan, especially among younger readers, is due primarily to the fact that most young Japanese access the Internet through their phones (which are a generation more advanced than what’s available in the US) rather than on desktop computers. Kids don’t have a lot of privacy in their homes, he explains further, so they spend most of their time out and about on the streets, using keitai for entertainment and social navigation.

Yourgrau believes that the popularity of keitai fiction in Japan, especially among younger readers, is due primarily to the fact that most young Japanese access the Internet through their phones (which are a generation more advanced than what’s available in the US) rather than on desktop computers. Kids don’t have a lot of privacy in their homes, he explains further, so they spend most of their time out and about on the streets, using keitai for entertainment and social navigation.

And the fictions are as mobile as their users, migrating fluidly from one technological context to another. Many keitai novels, Yourgrau explains, frequently “emerge from pools of people on web pages” before migrating onto keitai screens. Upon scoring a success on phones, they then frequently make their way onto the bestseller list in print form (the image is the print edition of Yourgrau’s recent keitai cycle). A few have even been made into films.

Western publishers would do well to study this free-flowing model. A story need not be bound to one particular delivery mechanism, be it a cell phone, web page (or book). In fact, the ecology of forms can make a more comprehensive narrative universe. This is not only the accepted wisdom of cross-media marketing franchisers and brand blizzardeers (Spiderman the comic, Spiderman the action figure, the lunchbox, the movie, the game, the Halloween costume etc.), but an age-old principle underlying the transmission of culture. The Arthurian legends, for instance, weren’t spun in one single authoritative text, but in many different textual itertations over time, a plethora of visual depictions, oral storytelling, songs, objets d’art etc.

In the case of keitai fiction, there’s seems to be a relation between compression of form and expansiveness of transmission. Interestingly, Yourgrau writes his phone stories longhand with a pencil, then types them up on a computer:

I write my fiction longhand first. I need the pencil/pen in hand to connect to emotions. I then type up. For the first several books I used a typewriter, now I’m (late) on computer. But I find the computer too suited to Flow, not the weight of the individual word. I’ve half a mind to switch back to a typewriter…..

There’s an interesting paradox here: that the compression that makes for good Web or cell phone writing is not afforded by the actual tools of electronic composition, which much more favor a kind of verbal sprawl. With that in mind, it’s not surprising that several of the most successful keitai novels were composed entirely on phones, one carpal tunnel syndrome-inducing keypad stroke at a time. To digress… one wonders whether the bloat of much contemporary fiction is a direct effect of word processors and the ease of Inernet research. That would support the broader observation that the net, far from killing off books, seems to have acted like a bellows, greatly boosting (at least for the time being) the number of pages produced in print.

In any case, I can readily imagine why Yourgrau’s surreal miniatures fit so well in the keitai form, both as random time-fillers and as little social cherry bombs to detonate among friends -? stories plucked out of the air. I’ll conclude this not so compressed ramble with one of Yourgrau’s concise keitai hauntings:

EDGAR ALLAN POE RICE BALL (MEDIEVAL LANDSCAPE)

Disease strikes a distant town. The victims develop loathsome sores all over their bodies; at the same time they’re maddened by extreme lascivious impulses. Down street after street door after door is splashed with a crude red cross: inside, the lunatic disfigured coupling rages on nonstop – ?men, women, even children – ?until exhausted dawn, until death.

In the hills beyond town, a monk makes his way along a darkening road. He chews a stale rice ball for his supper as he goes, so as not to interrupt his march. His sandaled feet move one in front of the other inexorably. His staff leaves a trail of dots behind him in the dusty distances. At last he comes around the side of a hill and he stops. The prospect of the dim town spreads before him. A look of disturbance moves over his face, as he slowly chews the last of his rice ball. Even here the uneasy wind carries the grisly minglings of lamentation and carnal grunting The monk becomes watchful; he looks uneasily around him and grips his staff in both hands. Two figures are moving feverishly in the darkness ahead. They seem to prance toward him, half-naked, hideous, moaning hoarse endearments. The monk calls to his god as he raises his staff and prepares to meet them.

literature electrique

I’ve been meaning to post something for a while about The Reprover, or Le Reprobateur, a hugely impressive work of digital fiction by François Coulon, Paris-based digital writer. It includes excellent cartoons, live video of the main character and a witty text in French and elaborate English which expands and contracts – the same sentence blooming different additional clauses each time you pass a mouse across it. This is a deeply disconcerting effect at first, but once you’ve got used to it, a whole new kind of three dimensional reading emerges. It’s a fascinating idea which could only work on the web.

I’ve been meaning to post.. but haven’t got round to it. That’s why I need a Reprobateur, “someone who would be there simply to give us a bad conscience.” Part psychoanalyst, part priest, part bloke in a suit, the Reprover is a wonderful creation. The story is set in the 80s and you can navigate around it by spinning a 3D polyhedron. “It’s literature plus electricity!” says Coulon.

It’s also plus so many tricks and distractions that it’s hard to settle into – there’s too much fun to be had clicking, spinning and adjusting the layers of soundtrack to actually immerse oneself in the story. The Reprover is beautifully produced and costs real money: 16 Euros or 160 for institutions, but you can get an excellent taster by going to http://www.totonium.com.

I’ve been going back to this one several times for more. Once you’re signed up you can contact the narrator for free advice from your very own Reprover. You’ll wonder how you coped all those years without one.

a safe haven for fan culture

The Organization for Transformative Works is a new “nonprofit organization established by fans to serve the interests of fans by providing access to and preserving the history of fanworks and fan culture in its myriad forms.”

Interestingly, the OTW defines itself -? and by implication, fan culture in general -? as a “predominately female community.” The board of directors is made up of a distinguished and, diverging from fan culture norms, non-anonymous group of women academics spanning film studies, english, interaction design and law, and chaired by the bestselling fantasy author Naomi Novik (J.K. Rowling is not a member). In comments on his website, Ethan Zuckerman points out that

…it’s important to understand the definition of “fan culture” – media fandom, fanfic and vidding, a culture that’s predominantly female, though not exclusively so. I see this statement in OTW’s values as a reflection on the fact that politically-focused remixing of videos has received a great deal of attention from legal and media activists (Lessig, for instance) in recent years. Some women who’ve been involved with remixing television and movie clips for decades, producing sophisticated works often with incredibly primitive tools, are understandably pissed off that a new generation of political activists are being credited with “inventing the remix”.

In a nod to Virginia Woolf, next summer the OTW will launch “An Archive of One’s Own,” a space dedicated to the preservation and legal protection of fan-made works:

An Archive Of Our Own’s first goal is to create a new open-source software package to allow fans to host their own robust, full-featured archives, which can support even an archive on a very large scale of hundreds of thousands of stories and has the social networking features to make it easier for fans to connect to one another through their work.

Our second goal is to use this software to provide a noncommercial and nonprofit central hosting place for fanfiction and other transformative fanworks, where these can be sheltered by the advocacy of the OTW and take advantage of the OTW’s work in articulating the case for the legality and social value of these works.

OTW will also publish an academic journal and a public wiki devoted to fandom and fan culture history. All looks very promising.