lately i’ve been thinking about how the institute for the future of the book should be experimental in form as well as content – an organization whose work, when appropriate, is carried out in real time in a relatively public forum. one of the key themes of our first year has been the way a network adds value to an enterprise, whether that be a thought experiment, an attempt to create a collective memory, a curated archive of best practices, or a blog that gathers and processes the world around it. i sense we are feeling our way to new methods of organizing work and distributing the results, and i want to figure out ways to make that aspect of our effort more transparent, more available to the world. this probably calls for a reevaluation of (or a re-acquaintance with) our idea of what an institute actually is, or should be.

the university-based institute arose in the age of print. scholars gathering together to make headway in a particular area of inquiry wrote papers, edited journals, held symposia and printed books of the proceedings. if books are what humans have used to move big ideas around, institutes arose to focus attention on particular big ideas and to distribute the result of that attention, mostly via print. now, as the medium shifts from printed page to networked screen, the organization and methods of “institutes” will change as well.

how they will change is what we hope to find out, and in some small way, influence. so over the next year or so we’ll be trying out a variety of different approaches to presenting our work, and new ways of facilitating debate and discussion. hopefully, we’ll draw some of you in along the way.

here’s a first try. we’ve decided (see thinking out loud) to initiate a weekly discussion at the institute where we read a book (or article or….) and then have a no-holds discussion about it — hoping to at least begin to understand some of the first order questions about what we are doing and how it fits into our perspectives on society. mostly we’re hoping to get to a place where we are regularly asking these questions in our work (whether designing software, studying the web, holding a symposium, or encouraging new publishing projects), measuring technological developments against a sense of what kind of society we’d like to live in and how a particular technology might help or hinder our getting there.

the first discussion is focused on neil postman’s “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century.” following is the audio we recorded broken into annotated chapters. we would be interested in getting people’s feedback on both form and content. (jump to the discussion)

Category Archives: ebook

marketing books on mobile phones

Harper Collins Australia’s new MobileReader service beams information about new titles and authors, and even book excerpts, to a cellphone. They’re beginning with promotions of Dean Koontz, Paul Coelho and others.

(via textually)

“the minotaur project” featured at ELO

Kim’s hypermedia poem cluster, “The Minotaur Project,” is currently featured at the Electronic Literature Organization. Highly recommended.

introducing nexttext

The dawn of personal computing and the web has changed the way we learn, yet the tools of instruction have been sluggish to evolve. Nowhere is this more clear than with the printed textbook.

So the institute has launched nexttext, a project that seeks to accelerate the textbook’s evolution, onward from its current incarnation, the authoritative brick, toward something more fluid, more complete, and more alive – more fitting with this networked age.

Our aim is to encourage – through identifying existing experiments and facilitating new ones – the development of born-digital learning materials that will enhance, expand, and ultimately replace the printed textbook. To begin, we’ve set up a curated site showcasing the most significant digital learning experiments currently in the field. Our hunch is that by bringing these projects (and eventually, their creators) together in a single place, along with publishers and funders willing to take a risk, a concrete vision of the digital textbook for the near future might emerge. And actually happen.

So check out the site, comment, and by all means recommend other projects you think belong there. What’s up now is a seed group – things that have gotten our wheels turning so far – to be grown and expanded by the collective intelligence of the community.

thinking out loud

on sunday one of my colleagues, kim white, posted a short essay on if:book, Losing America, which eloquently stated her horror at realizing how far america has slipped from its oft-stated ideals of equality and justice. as kim said “I thought America (even under the current administration) had something to do with being civilized, humane and fair. I don’t anymore.”

kim ended her piece with a parenthetical statement:

(The above has nothing and everything to do with the future of the book.)

the four of us met around a table in the institute’s new williamsburg digs yesterday and discussed why we thought kim’s statement did or didn’t belong on if:book. the result — a resounding YES.

if you’ve been reading if:book for awhile you’ve probably encountered the phrase, “we use the word book to refer to the vehicle humans use to move big ideas around society.” of course many, if not most books are about entertainment or personal improvement, but still the most important social role of books (and their close dead-tree cousins, newspapers, magazines etc.) has been to enable a conversation across space and time about the crucial issues facing society.

we realize that for the institute to make a difference we need to be asking more the right questions.although our blog covers a wide-range of technical developments relating to the evolution of communication as it goes digital, we’ve tried hard not to be simple cheerleaders for gee-whiz technology. the acid-test is not whether something is “cool” but whether and in what ways it might change the human condition.

which is why kim’s post seems so pertinent. for us it was a wake-up call reinforcing our notion that what we do exists in a social, not a technological context. what good will it be if we come up with nifty new technology for communication if the context for the communication is increasingly divorced from a caring and just social contract. Kim’s post made us realize that we have been underemphasizing the social context of our work.

as we discuss the implications of all this, we’ll try as much as possible to make these discussions “public” and to invite everyone to think it through with us.

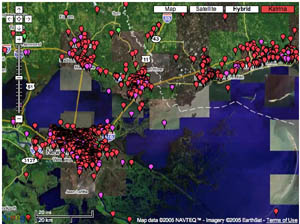

katrina and the interactive atlas

Interactive maps help those of us not in the region to grasp the terrain of devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina. These maps are suggestive of a new paradigm for the digital page – an interactive canvas, or territory, through which the reader can zoom through orders of magnitude.

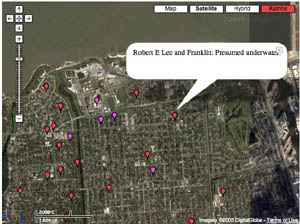

Most talked about is the “visual wiki” at scipionus.com – a re-tooling of Google maps that invites users to post tabs with information pertaining to specific locales (as fine-grained as streetcorners). Tabs are editable and are supposed to be used only for concrete reports, though many have posted pleas for news of specific missing persons or of the condition of certain blocks. Some samples:

“Saw news video 9/2/05 of corner street sign at 10th St. & Pontchartrain Blvd. Water level was about 6 in. below. green street signs.”

“the Ashley’s are in Prattville AL”

“4400 Calumet — dry on Weds?”

“as of 5:00 pm.. the streets from wilson canal to transcontinental are COMPLETELY DRY! source from somebody who stayed and called to tell us the info.”

“Dylan Nash anyone?? call 919-7307018”

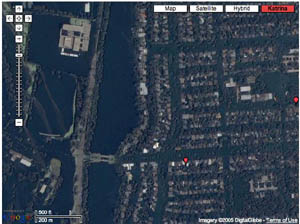

The maps include post-Katrina satellite imagery, which reveals, upon zooming in, horrifying grids of inundated streets, stadiums filled up like soup tureens, city parks transformed into swamps. Wired recently ran a piece about sciponius.

Before & After:

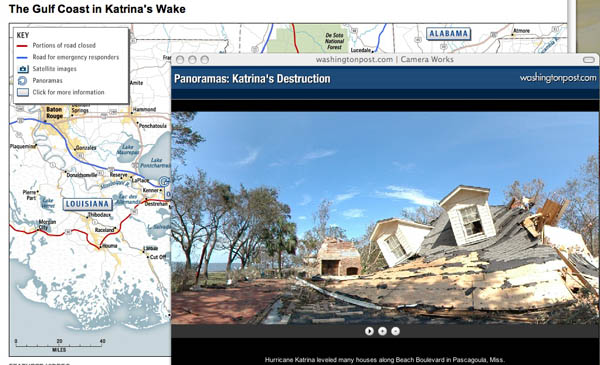

I was also impressed by the interactive maps on washingtonpost.com.

Click on spinning wheels at various points along the coastline and windows pop up with scrolling panoramic shots. Quite stunning. You can click the screen and drag the scroll in either direction, stop it, speed it up, and even pull it up and down to reveal glimpses of the sky or ground. Photojournalism is given new room to play on online newspapers.

(No Need to Click Here – I’m just claiming my feed at Feedster feedster:d50fedfc363272797584521a06a79da5)

the selected, annotated outbox of dave eggers

Email killed the practice of letter-writing so suddenly that we haven’t a chance to think about the consequences. The Times Book Review ran an essay this weekend on the problem this poses for literary historians, biographers and archivists, who long have relied on collected letters and papers to fill in the gaps between a writer’s published work. In the same review, the Times covers a new biography of the legendary critic Edmund Wilson largely based on his correspondences, and last week covered a new collection of the letters of poet James Wright. Letters are often treated as literature in themselves.

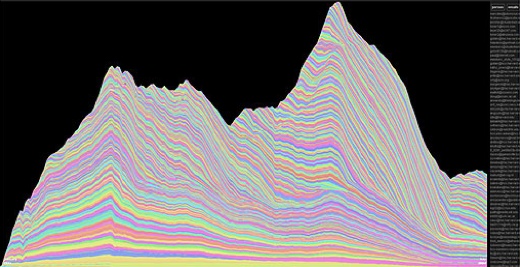

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

There isn’t necessarily anything less rich about email correspondence. It excels at capturing a vibrant volley of words with great immediacy, whereas paper letters permit deeper communiques, fewer and father between. But in some cases, these characterizations do not hold up. With reliable postal service, letters can fly back and forth quite rapidly. And just because an email suddenly appears in your box does not mean that it will be immediately read, let alone replied to. Sometimes we write long email letters, expecting that the receiver is busy and will take time to reply. These differences, true and false, are worth evaluating.

But if collected emails are to become a literary tool, there is no question that we will need more reliable ways of archiving and preserving digital correspondence. We will also need new editorial approaches for collecting and publishing them. A printed volume, or series of volumes, might be insufficient for presenting a massive 4 gigabyte email archive by Dave Eggers (No one wants to read the phone book from cover to cover). And according to the Times piece, Eggers’ agent Andrew Wylie is mulling over such a project. What would make more sense is an electronic edition that is essentially a selected or complete annotated Eggers Outbox, with folders and tags provided for categorization, a powerful search function, and the ability to organize according to your own interests. There would also be browsing and skimming tools that would allow a reader to move rapidly across vast tracts of correspondence and still find what they are looking for. And maybe, a way to email the author yourself and become a part of the living archive.

if:book one of five blogs for blogday

Writing and the Digital Life, a brand new weblog with interests very similar to ours, just went live today and has kindly named us among five blogs for “blogday.” I look forward to reading their site.

treasuremytext: a networked SMS book

treasuremytext is a free British service that allows you to save text messages from your phone to the web on an anonymous, communal log, or “slog.” Recent messages appear in a column on the main site where they can be read by all and sundry, subscribed to by feed, and even loaded onto an iPod as plain text files. jill/txt has a transcript from about two weeks back:

trying to convince myself that there was nothing there but i still find myself thinking about you

night nimet . . . . i miss you

How about sorting that taxi out for next week? For real?

Ok smart arse when you are there then! And then i will fix your issues for you, all of them!

U have beautifull eyes

Dont ring ill b down bout halfpast babes

Me to hes just arrived txt u l8r baby

Nite nite xxx

Nite nite fat sexy bum.Txt u tomoz nite nite xxxx

Not exactly prize-winning stuff, but has a nice dreamy flow of chatter plucked out of the air. Reminds me a bit of a game I played in elementary school where you go around a circle and improvise a story in broken-off pieces. Reading the site today, the entries seem to have taken on a smuttier tone. And a good number aren’t in English. But an intriguing experiment nonetheless.

But it would be more interesting if the logs had some focus. Something like the City Chromosomes project, which is building a networked chronicle of the city of Antwerp, all by SMS.

the blog as a record of reading

An excellent essay in last month’s Common-Place, “Blogging in the Early Republic” by W. Caleb McDaniel, examines the historical antecedents of the present blogging craze, looking not to the usual suspects – world shakers like Martin Luther and Thomas Paine – but to an obscure 19th century abolitionist named Henry Clarke Wright. Wright was a prolific writer and tireless lecturer on a variety of liberal causes. He was also “an inveterate journal keeper,” filling over a hundred diaries through the course of his life. And on top of that, he was an avid reader, the diaries serving as a record of his voluminous consumption. McDaniel writes:

While private, the journals were also public. Wright mailed pages and even whole volumes to his friends or read them excerpts from the diaries, and many pages were later published in his numerous books. Thus, as his biographer Lewis Perry notes, in the case of Wright, “distinctions between private and public, between diaries and published writings, meant little.”

Wright’s journaling habit is interesting not for any noticeable impact it had on the politics or public discourse of his day; nor (at least for our purposes) for anything particularly memorable he may have written. Nor is it interesting for the fact that he was an active journal-keeper, since the practice was widespread in his time. Wright’s case is worth revisiting because it is typical — typical not just of his time, but of ours. It tells a strikingly familiar story: the story of a reader awash in a flood of information.

Wright, in his lifetime, experienced an incredible proliferation of printed materials, especially newspapers. The print revolution begun in Germany 400 years before had suddenly gone into overdrive.

The growth of the empire of newspapers had two related effects on the practices of American readers. First, the new surplus of print meant that there was more to read. Whereas readers in the colonial period had been intensive readers of selected texts like the Bible and devotional literature, by 1850 they were extensive readers, who could browse and choose from a staggering array of reading choices. Second, the shift from deference to democratization encouraged individual readers to indulge their own preferences for particular kinds of reading, preferences that were exploited and targeted by antebellum publishers. In short, readers had more printed materials to choose from, more freedom to choose, and more printed materials that were tailored to their choices.

Wright’s journaling was his way of metabolizing this deluge of print, and his story draws attention to a key aspect of blogging that is often overshadowed by the more popular narrative – that of the latter-day pamphleteer, the lone political blogger chipping away at mainstream media hegemony. The fact is that most blogs are not political. The star pundits that have risen to prominence in recent years are by no means representative of the world’s roughly 15 million bloggers. Yet there is one crucial characteristic that is shared by all of them – by the knitting bloggers, the dog bloggers, the macrobiotic cooking bloggers, along with the Instapundits and Daily Koses: they are all records of reading.

The blog provides a means of processing and selecting from an overwhelming abundance of written matter, and of publishing that record, with commentary, for anyone who cares to read it. In some cases, these “readings” become influential in themselves, and multiple readers engage in conversations across blogs. But treating blogging first as a reading practice, and second as its own genre of writing, political or otherwise, is useful in forming a more complete picture of this new/old phenomenon. To be sure, today’s abundance makes the surge in 18th century printing look like a light sprinkle. But the fundamental problem for readers is no different. Fortunately, blogs provide us with that much more power to record and annotate our readings in a way that can be shared with others. We return to Bob’s observation that something profound is happening to our media consumption patterns.

As McDaniel puts it:

…readers, in a culture of abundant reading material, regularly seek out other readers, either by becoming writers themselves or by sharing their records of reading with others. That process, of course, requires cultural conditions that value democratic rather than deferential ideals of authority. But to explain how new habits of reading and writing develop, those cultural conditions matter as much–perhaps more–than economic or technological innovations. As Tocqueville knew, the explosion of newspapers in America was not just a result of their cheapness or their means of production, any more than the explosion of blogging is just a result of the fact that free and user-friendly software like Blogger is available. Perhaps, instead, blogging is the literate person’s new outlet for an old need. In Wright’s words, it is the need “to see more of what is going on around me.” And in print cultures where there is more to see, it takes reading, writing, and association in order to see more.

(image: “old men reading” by nobody, via Flickr)