According to a Dec 11 New York Times article, Daniel Brandt, a book indexer who runs the site Wikipedia Watch, helped to flush out the man who posted the false biography of USA Today and Freedom Forum founder John Seigenthaler on Wikipedia. After Brandt discovered the post issued from a small delivery company in Nashville, the man in question — 38-year-old Brian Chase — sent a letter of apology to Seigenthaler and resigned from his job as operations manager at the company.

According to the Times, Chase claims that he didn’t realize that Wikipedia was used as a serious research tool: he posted the information to shock a co-worker who was familiar with the Seigenthaler family. Seigenthaler, who complained in a USA Today editorial last week about the protections afforded to the “volunteer vandals” who post anonymously in cyberspace, told the New York Times that he would not seek damages from Chase.

Responding to the fallout from Seigenthaler’s USA Today editorial, Wikipedia founder James Wales changed Wikipedia’s policies so that posters now must all be registered with Wikipedia. But, as Brandt shows, it’s takes work to remain anonymous in cyberspace. Though I’m not sure that I beleive Chase’s professed astonishment that anyone would take his post seriously (why else would it shock his co-worker?), it seems clear that he didn’t think what he was doing so outrageous that he ought to make a serious effort to hide his tracks.

Meanwhile, Wales has become somewhat irked by Seignthaler’s continuing attacks on Wikipedia. Posting to the threaded discussion of the issue on the mailing list of the Association for Internet Researchers, Wikipedia’s founder expressed exasperation about Seigenthaler’s telling the Associated Press this morning that “Wikipedia is inviting [more regulation of the internet] by its allowing irresponsible vandals to write anything they want about anybody.” Wales wrote:

*sigh* Facts about our policies on vandalism are not hard to come by. A statement like Seigenthaler’s, a statement that is egregiously false, would not last long at all at Wikipedia.

For the record, it is just absurd to say that Wikipedia allows “irresponsible vandals to write anything they want about anybody.”

–Jimbo

Monthly Archives: December 2005

ElectraPress

Kathleen Fitzpatrick has put forth a very exciting proposal calling for the formation of an electronic academic press. Recognizing the crisis in academic publishing, particularly with the humanities, Fitzpatrick argues that:

The choice that we in the humanities are left with is to remain tethered to a dying system or to move forward into a mode of publishing and distribution that will remain economically and intellectually supportable into the future.

i’ve got my fingers crossed that Kathleen and her future colleagues have the courage to go way beyond PDF and print-on-demand; the more Electrapress embraces new forms of born-digital documents especially in an open-access pubishing environment, the more interesting the new enterprise will be.

class, cheating and gaming

The New York Times reports that a company in China is hiring people to play Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOG), like World of Warcraft or EverQuest. Employees develop avatars (or characters) and earn resources. Then, the company sells these efforts to affluent online gamers who do not have the time or inclination to play the early stages of the games themselves.

Finding hacks or ways to get around the intended game play is nothing new. I will confess that I have used cheat codes and hacks in playing video games. One of the first ones I’ve ever used, was in Super Mario Brothers on the original Nintendo Entertainment System. The Multiple 1-Ups: World 3-1 was a big favorite.

The article also briefly mentions something that I’ve been fascinated by: selling the results of your game play on auctions site, such as ebay. These services have turned game play into commodities, and we can actually determine valuations and costs of game play.

It made me to think about the character Hiro Protagonist in Neal Stephenson’s Snowcrash, a pizza delivery guy in the real world and lethal warrior in the “Metaverse.” He was an exception to the norm and socio-economic status usually carried over into the virtual reality because more realistic avatars were expensive. To actually see that happen in the game spaces of MMOGs by the purchasing of advanced players is quite amazing.

Why do I find that these gamers are cheating? In the era of non-linear information, I select and read only the parts of a text I deem to be relevant. I’ve skipped over parts of movies and watched another part again and again. Isn’t this the same thing? The troubling aspect of this phenomenon is that it is bringing class differentiation into game space. Although gaming itself is a leisure activity, the idea that you can spend your way into succeeding at a MMOG, removes my perceived innocence of that game space.

where we’ve been, where we’re going

This past week at if:book we’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between this weblog and the work we do. We decided that while if:book has done a fine job reflecting and provoking the conversations we have at the Institute, we wanted to make sure that it also seems as coherent to our readers as it does to us. With that in mind, we’ve decided to begin posting a weekly roundup of our blog posts, in which we synthesize (as much a possible) what we’ve been thinking and talking about from Monday to Friday.

So here goes. This week we spent a lot of time reflecting on simulation and virtuality. In part, this reflection grew out of our collective reading of a Tom Zengotita’s book Mediated, which discusses (among other things) the link between alienation from the “real” through digital mediation and increased solipsism. Bob seemed especially interested in the dialectic relationship between, on one hand, the opportunity for access afforded by ever-more sophisticated form of simulation, and, on the other, the sense that something must be lost when as the encounter with the “real” recedes entirely.

This, in turn, led to further conversation about what we might think of as the “loss of the real” in the transition from books on paper to books on a computer screen. On one hand, there seems to be a tremendous amount of anxiety that Google Book Search might somehow make actual books irrelevant and thus destroy reading and writing practices linked to the bound book. On the other hand, one could take the position of Cory Doctorow that books as objects are overrated, and challenge the idea that a book needs to be digitally embodied to be “real.”

As the debate over Google Book Search continually reminds us, one of the most challenging things in sifting through discussions of emerging media forms is learning to tell the difference between nostalgia and useful critical insight. Often the two are hopelessly intertwined; in this week’s debates about Wikipedia, for example, discussion of how to make the open-source encyclopedia more useful was often tempered by the suggestion that encyclopedias of the past were always be superior to Wikipedia, an assertion easily challenged by a quick browse through some old encyclopedias.

Finally, I want to mention that we finally got around to setting up a del.icio.us account. There will be a formal link on the blog up soon, but you can take a look now. It will expand quickly.

the poetry archive – nice but a bit mixed up

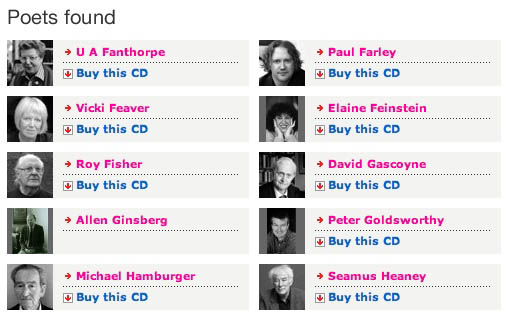

Last week U.K. Poet Laureate Andrew Motion and recording producer Richard Carrington rolled out The Poetry Archive, a free (sort of) web library that aims to be “the world’s premier online collection of recordings of poets reading their work” — “to help make poetry accessible, relevant and enjoyable to a wide audience.”  The archive naturally focuses on British poets, but offers a significant selection of english-language writers from the U.S. and the British Commonwealth countries. Seamus Heaney is serving as president of the archive.

The archive naturally focuses on British poets, but offers a significant selection of english-language writers from the U.S. and the British Commonwealth countries. Seamus Heaney is serving as president of the archive.

For each poet, a few streamable mp3s are available, including some rare historic recordings dating back to the earliest days of sound capture, from Robert Browning to Langston Hughes. The archive also curates a modest collection of children’s poetry, and invites teachers to use these and other recordings in the classroom, also providing tips for contacting poets so schools, booksellers and community organizations (again, this is focused on Great Britain) can arrange readings and workshops. While some of this advice seems useful, but it reads more like a public relations/ecudation services page on a publisher’s website. Is this a public archive or a poets’ guild?

The Poetry Archive is a nice resource as both historic repository and contemporary showcase, but the mission seems a bit muddled. They say they’re an archive, but it feels more like a CD store.

Throughout, the archive seems an odd mix of public service and professional leverage for contemporary poets. That’s all well and good, but it could stand a bit more of the former. Beyond the free audio offerings (which are quite skimpy), CDs are available for purchase that include a much larger selection of recordings. The archive is non-profit, and they seem to be counting in significant part on these sales to maintain operations. Still, I would add more free audio, and focus on selling individual recordings and playlists as downloads — the iTunes model. Having streaming teasers and for-sale CDs as the only distribution models seems wrong-headed, and a bit disingenuous if they are to call themselves an archive. It would also be smart to sell subscriptions to the entire archive, with institutional rates for schools. Podcasting would also be a good idea — a poem a day to take with you on your iPod, weaving poetry into daily life.

There’s a growing demand on the web for the spoken word, from audiobooks, podcasts, to performed poetry. The archive would probably do a lot better if they made more of their collection free, and at the same time provided a greater variety of ways to purchase recordings.

tipping point?

An article by Eileen Gifford Fenton and Roger C. Schonfeld in this morning’s Inside Higher Ed claims that over the past year, libraries have accelerated the transition towards purchasing only electronic journals, leaving many publishers of print journals scrambling to make the transition to an online format:

Faced with resource constraints, librarians have been required to make hard choices, electing not to purchase the print version but only to license electronic access to many journals — a step more easily made in light of growing faculty acceptance of the electronic format. Consequently, especially in the sciences, but increasingly even in the humanities, library demand for print has begun to fall. As demand for print journals continues to decline and economies of scale of print collections are lost, there is likely to be a tipping point at which continued collecting of print no longer makes sense and libraries begin to rely only upon journals that are available electronically.

According to Fenton and Schonfeld, this imminent “tipping point” will be a good thing for larger publishing houses which have already begun to embrace an electronic-only format, but smaller nonprofit publishers might “suffer dramatically” if they don’t have the means to convert to an electronic format in time. If they fail, and no one is positioned to help them, “the alternative may be the replacement of many of these journals with blogs, repositories, or other less formal distribution models.”

Fenton and Schonfeld’s point that electronic distribution might substantially change the format of some smaller journals echoes other expressions of concern about the rise of “informal” academic journals and repositories, mainly voiced by scientists who worry about the decline of peer review. Most notably, the Royal Society of London issued a statement on Nov. 24 warning that peer-reviewed scientific journals were threatened by the rise of “open access journals, archives and repositories.”

According to the Royal Society, the main problem in the sciences is that government and nonprofit funding organizations are pressing researchers to publish in open-access journals, in order to “stop commercial publishers from making profits from the publication of research that has been funded from the public purse.” While this is a noble principle, the Society argued, it undermines the foundations of peer review and compels scientists to publish in formats that might be unsustainable:

The worst-case scenario is that funders could force a rapid change in practice, which encourages the introduction of new journals, archives and repositories that cannot be sustained in the long term, but which simultaneously forces the closure of existing peer-reviewed journals that have a long-track record for gradually evolving in response to the needs of the research community over the past 340 years. That would be disastrous for the research community.

There’s more than a whiff of resistance to change in the Royal Society’s citing of 340 years of precedent; more to the point however, their position statement downplays the depth of the fundamental opposition between the open access movement in science and traditional journals. As Roger Chartier notes in a recent issue of Critical Inquiry, “Two different logics are at issue here: the logic of free communication, which is associated with the ideal of the Enlightenment that upheld at the sharing of knowledge, and the logic of publishing based on the notion of author’s rights and commercial gain.”

As we’ve discussed previously on if:book. the fate of peer review in electronic age is an open question: as long as peer review is tied to the logic of publishing, its fate will be determined at least as much by the still evolving market for electronic distribution as by the needs of the various research communities which have traditionally valued it as a method of assessment.

pulitzers will accept online journalism

Online news is now fair game for all fourteen journalism categories of the Pulitzer Prize (previously only the Public Service category accepted online entries). However, online portions of prize submissions must be text-based, and the only web-exclusive content accepted will be in the breaking news reporting and breaking news photography categories.  But this presumably opens the door to some Katrina-related Pulitzers this April. I would put my bets on nola.com, the New Orleans Times-Picayune site that kept reports flying online throughout the hurricane.

But this presumably opens the door to some Katrina-related Pulitzers this April. I would put my bets on nola.com, the New Orleans Times-Picayune site that kept reports flying online throughout the hurricane.

Of course, the significance of this is mainly symbolic. When the super-prestigious Pulitzer (that’s him to the right) starts to re-align its operations, you know there are bigger plate tectonics at work. This would seem to herald an eventual embrace of blogs, most obviously in the areas of commentary, beat reporting, community service, and explanatory reporting (though investigative reporting may not be far off). The committee would do well to consider adding a “news analysis” category for all the fantastic websites, many of them blogs, that help readers make sense of the news and act as a collective watchdog for the press.

Also, while the Pulitzer changes evince a clear preference for the written word, it seems inevitable that inter-media journalism will continue to gain in both quality and legitimacy. We’ll probably look back on all the Katrina coverage as the watershed moment. Newspapers (some of them anyway) will figure out that to stay relevant, and distinctive enough not to be pulled apart by aggregators like Google or Yahoo news search, they will have to weave a richer tapestry of traditional reporting, commentary, features, and rich multimedia: a unique window to the world.

Nola.com didn’t just provide good, constant coverage, it saved lives. It was an indispensible, unique portal that could not be matched by any aggregator (though harnessing the power of aggregation is part of what made it successful). The crisis of the hurricane put in relief what could be a more everyday strategy for newspapers. The NY Times currently is experimenting with this, developing a range of multimedia features and cordoning off premium content behind its Select pay wall. While I don’t think they’ve yet figured out the right combination of premium content to attract large numbers of paying web subscribers, their efforts shouldn’t necessarily be dismissed.

Discussions on the future of the news industry usually center around business models and the problem of solvency with a web-based model. These questions are by no means trivial, but what they tend to leave out is how the evolving forms of journalism might affect what readers consider valuable. And value is, after all, what you can charge for. It’s fatalistic to assume that the web’s entropic power will just continue to wear down news institutions until they vanish. The tendency on the web toward fragmentation is indeed strong, but I wouldn’t underestimate the attraction of a quality product.

A couple of years ago, file sharing seemed to spell doom for the music industry, but today online music retailers are outselling most physical stores. Perhaps there is a way for news as well, but the news will have to change. Dan Gillmor is someone who has understood this for quite some time, and I quote from a rather prescient opinion piece he wrote back in 1997 when the Pulitzers were just beginning to wonder what to do about all this new media (this came up today on the Poynter Online-News list):

When we take journalism into the digital realm, media distinctions lose their meaning. My newspaper is creating multimedia journalism, including video reports, for our Web site. We strongly believe that the online component of our work augments what we sometimes call the “dead-tree” edition, the newspaper itself. Meanwhile, CNN is running text articles on its Web site, adding context to video reports.

So you have to ask a simple question or two: Online, what’s a newspaper? What’s a broadcaster?

Suppose CNN posts a particularly fine video report on its Web site, augmented by old-fashioned text and graphics. If the Pulitzer Prizes are o pen to online content, the CNN report should be just as valid an entry as, say, a newspaper series posted online and augmented with video.

And what about the occasionally exceptional journalism we’re seeing from Web sites (or on CD-ROMs) produced by magazines, newsletters, online-only companies or even self-appointed gadflies? Corporate propaganda obviously will fail the Pulitzer test, but is a Microsoft-sponsored expose of venality by a competitor automatically invalid when it’s posted on the Microsoft Network news site or MSNBC? Drawing these lines will take serious wisdom, unless the Pulitzer people decide simply to ignore trends and keep the prizes the way they are, in which case the awards will become quaint – or worse, irrelevant.

I’m also intrigued by another change made by the Pulitzer committee (from the A.P.):

In a separate change, the upcoming Pulitzer guidelines for the feature writing category will give ”prime consideration to quality of writing, originality and concision.” The previous guidelines gave ”prime consideration to high literary quality and originality.”

Drop the “literary” and add “concision.” A move to brevity and a more colloquial character are already greatly in evidence in the blogosphere and it’s beginning to feed back into the establishment press. Employing once again the trusty old Pulitzer as barometer, this suggests that that most basic of journalistic forms — “the story” — is changing.

a new way to pen pal

Here is another example of users latching onto unexpected features of a technology. Time magazine reports on the surprising popularity of their “Skype Me” mode which allows Skype users to basically cold call each other. This feature seems to be popular with people abroad (especially in China) looking for opportunities to practice their English with people in the US, in a way that resembles pen pals.

One might say that is really just one big chat room, although chat rooms are still text based. The interesting part of the Skype Me community is that it shifts pen pals from a text based activity to an oral based one. The impact that Skype has on pen pals highlights the interplay which digital technology encourages between written and oral forms. Is this a case of the Internet expanding the reach of a community or another example of technology reducing the emphasis on developing writing skills?

google libraries podcast now available

interview with cory doctorow in openbusiness

There’s an interview with Cory Doctorow in Openbusiness this morning. Doctorow, who distributes his books for free on the internet, envisions a future in which writers see free electronic distibution as a valuable component of their writing and publishing process. This means, in turn, that writers and publishers need to realize that ebooks and paper books have distinct differences:

Ebooks need to embrace their nature. The distinctive value of ebooks is orthogonal to the value of paper books, and it revolves around the mix-ability and send-ability of electronic text. The more you constrain an ebook’s distinctive value propositions — that is, the more you restrict a reader’s ability to copy, transport or transform an ebook — the more it has to be valued on the same axes as a paper-book. Ebooks *fail* on those axes.

On first read, I thought that Doctorow, much like Julia Keller in her Nov. 27 Chicago Tribune article, wanted to have it both ways: he acknowledges that, in some ways, ebooks challenge the idea of the paper books, but he also suggests that the paper book will remain unaffected by these challenges. But then I read more of Doctorow’s ideas about writing, and realized that, for Doctorow, the malleability of the digital format only draws attention to the fact that books are not always as “congealed” as their material nature suggests:

I take the view that the book is a “practice” — a collection of social and economic and artistic activities — and not an “object.” Viewing the book as a “practice” instead of an object is a pretty radical notion, and it begs the question: just what the hell is a book?

I like this idea of the book as practice, though I don’t think it’s an idea that would, or could, be embraced by all writers. It’s interesting to ponder the ways in which some writers are much more invested in the “thingness” of books than others — usually, I find myself thinking about the kinds of readers who tend to be more invested in the idea of books as objects.