In an interview in CNET today, Daniel Brandt of Wikipedia Watch — the man who tracked down Brian Chase, the author of the false biography of John Seigenthaler on Wikipedia — details the process he used to track Chase down. I found it an interesting reality check on the idea of online anonymity. I was also a bit nonplussed by the fact that Brandt created a phony identity for himself in order to discover who had created a fake version of the real Seigenthaler. According to Brandt:

All I had was the IP address and the date and timestamp, and the various databases said it was a BellSouth DSL account in Nashville. I started playing with the search engines and using different tools to try to see if I could find out more about that IP address. They wouldn’t respond to trace router pings, which means that they were blocked at a firewall, probably at BellSouth…But very strangely, there was a server on the IP address. You almost never see that, since at most companies, your browsers and your servers are on different IP addresses. Only a very small company that didn’t know what it was doing would have that kind of arrangement. I put in the IP address directly, and then it comes back and said, “Welcome to Rush Delivery.” It didn’t occur to me for about 30 minutes that maybe that was the name of a business in Nashville. Sure enough they had a one-page Web site. So the next day I sent them a fax. [they didn’t respond, and] The next night, I got the idea of sending a phony e-mail, I mean an e-mail under a phony name, phony account. When they responded, sure enough, the originating IP address matched the one that was in Seigenthaler’s column.

Overall, I’m still having mixed feelings about Brandt’s “bust” of Brian Chase — mostly because of the way the event has skewed discussion of Wikipedia, but partly because Chase’s outing seems to have damaged the hapless-seeming Chase much more than Seigenthaler had been damaged by the initial fake post. The CNET interview suggests that Brandt might also have some regrets about the fallout over Chase, though Brandt frames his concern as yet another critique of Wikipedia. Brandt claims he is uncomfortable about the fact that Chase has a Wikipedia biography, since “when this poor guy is trying to send out his resume,” employers will google him, find the Wikipedia entry, and refuse to hire him: since Wikipedia entries are not as ephemeral as news articles, he adds, the entry is actually “an invasion of privacy even more than getting your name in the newspaper.” This seems to be an odd bit of reasoning, since Brandt, after all, was the one who made Chase notorious.

When asked by the CNET interviewer how he would “fix” Wikipedia, Brandt maintained an emphasis on the idea that biographical entries are Wikipedia’s Achilles heel, an belief which is tied, perhaps, to his own reasons for taking Wikipedia to task — a prominent draft resister in the 1960s, Brandt discovered that his own Wikipedia post had links he considered unflattering. He explained to CNET that his first priority would be to “freeze” biographies on the site which had been checked for accuracy:

I would go and take all the biographical articles on living persons and take them out of the publicly editable Wikipedia and put them in a sandbox that’s only open to registered users. That keeps out all spiders and scrapers. And then you work on all these biographies and get them up to snuff and then put them back in the main Wikipedia for public access but lock them so they cannot be edited. If you need to add more information, you go through the process again. I know that’s a drastic change in ideology because Wikipedia’s ideology says that the more tweaks you get from the masses, the better and better the article gets and that quantity leads to improved quality irrevocably. Their position is that the Seigenthaler thing just slipped through the crack. Well, I don’t buy that because they don’t know how many other Seigenthaler situations are lurking out there.

“Seigenthaler situations.” This term could either come in to use as a term to refer to the dubious accuracy of an online post — or, alternately, to refer to a phobic response to open-source knowledge construction. Time will tell.

Meanwhile, in the pro-Wikipedia world, an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education today notes that a group of Wikipedia fans have decided to try to create a Wikiversity, a learning center based on Wiki open-source principles. According to the Chronicle, “It’s not clear exactly how extensive Wikiversity would be. Some think it should serve only as a repository for educational materials; others think it should also play host to online courses; and still others want it to offer degrees.” I’m curious to see if anything like a Wikiversity could get off the group, and how it will address the tension around open-source knowledge that been foregrounded by the Wikipedia-bashing that has taken place over the past few weeks.

Finally, there’s a great defense of Wikipedia in Danah Boyd’s Apophenia. Among other things, Boyd writes:

We should be teaching our students how to interpret the materials they get on the web, not banning them from it. We should be correcting inaccuracies that we find rather than protesting the system. We have the knowledge to be able to do this, but all too often, we’re acting like elitist children. In this way, i believe academics are more likely to lose credibility than Wikipedia.

Liz Barry and Bill Wetzel, the people behind

Liz Barry and Bill Wetzel, the people behind

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did

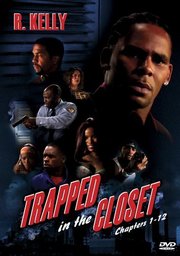

Most of the people reading this blog probably don’t give R. Kelly – the R&B singer known for his buttery voice and slippery morals – the attention that I do, which is completely understandable. But unfortunate, because he’s very much worth keeping an eye on. For the past six months, he’s been engaged in the most formally interesting experiment in pop music in a while. I’m referring, of course, to “Trapped in the Closet”. Bear with me a bit: while it might seem like I’m off on a frolic of my own, this will get around to having something to do with the future of the book.

Most of the people reading this blog probably don’t give R. Kelly – the R&B singer known for his buttery voice and slippery morals – the attention that I do, which is completely understandable. But unfortunate, because he’s very much worth keeping an eye on. For the past six months, he’s been engaged in the most formally interesting experiment in pop music in a while. I’m referring, of course, to “Trapped in the Closet”. Bear with me a bit: while it might seem like I’m off on a frolic of my own, this will get around to having something to do with the future of the book. For the next seven chapters, Kelly moved directly to video: he’s just released a DVD video of the first twelve chapters, where he and others act out the drama he’s narrating for thirty-nine minutes. New characters are introduced and the plot becomes steadily more labyrinthine (a midget and an allergy to cherries figure prominently) and fails to resolve much of anything. Kelly’s said to be busy thinking up a dozen more installments to the story. Through it all, the music remains the same; each episode is still three minute pop song, which do get played on the radio as such. Wikipedia does have a

For the next seven chapters, Kelly moved directly to video: he’s just released a DVD video of the first twelve chapters, where he and others act out the drama he’s narrating for thirty-nine minutes. New characters are introduced and the plot becomes steadily more labyrinthine (a midget and an allergy to cherries figure prominently) and fails to resolve much of anything. Kelly’s said to be busy thinking up a dozen more installments to the story. Through it all, the music remains the same; each episode is still three minute pop song, which do get played on the radio as such. Wikipedia does have a  An example at hand: a friend gave my girlfriend a copy of

An example at hand: a friend gave my girlfriend a copy of  It might be best explained by looking at the difference between Mastering the Art of French Cooking & Powell’s book. The former was conceived as a unified whole: it’s a single big idea, elucidated in steps, from the simple to the complicated. Later parts of that book are built upon the former: they don’t work well by themselves unless you’ve already absorbed the earlier information. Julie & Julia is constructed as a series of snapshots from the life of the author, each of which seeks to be individually interesting in and of itself. How does this play out in the pages of the book? An easy example: Powell’s sex life keeps popping up in a rather gratuitous fashion. The subject isn’t without relevance in a culinary work (

It might be best explained by looking at the difference between Mastering the Art of French Cooking & Powell’s book. The former was conceived as a unified whole: it’s a single big idea, elucidated in steps, from the simple to the complicated. Later parts of that book are built upon the former: they don’t work well by themselves unless you’ve already absorbed the earlier information. Julie & Julia is constructed as a series of snapshots from the life of the author, each of which seeks to be individually interesting in and of itself. How does this play out in the pages of the book? An easy example: Powell’s sex life keeps popping up in a rather gratuitous fashion. The subject isn’t without relevance in a culinary work ( A Dec 6th article in

A Dec 6th article in