The institute is pleased to announce the release of the blog Without Gods. Mitchell Stephens is using this blog as a public workshop and forum for his work on his latest book which focuses on the history of atheism.

The wikipedia debate continues as Chris Anderson of Wired Magazine weighs in that people are uncomfortable with wikipedia because they cannot comprehend that emergent systems can produce “correct” answers on the marcoscale even if no one is really watching the microscale. Lisa poses that Anderson goes too far in the defense of wikipedia and that blind faith in the system is equally disconcerting, if not more so.

ITP Winter 2005 show had several institute related projects. Among them were explorations in digital graphic reinterpretation of poetry, student social networks, navigating New York through augmented reality, and manipulating video to document the city by freezing time and space.

Lisa discovered an interesting historical parallel in an article from Dial dating back to 1899. The specialized bookseller’s demise is lamented with the introduction of department store selling books as lost leader, not unlike today’s criticisms of Amazon. As libraries are increasing their relationships with the private sector, Lisa notes that some bookstores are playing a role in fostering intellectual and culture communities, a role which libraries traditionally held.

Lisa looked at Reed Johnson assertion in the Los Angeles Times that 2005 was the year that mass media has given way to the consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution.

The discourse on game space continues to evolve with Edward Castronova’s new book Synthetic Worlds. As millions of people spend more time in the immersive environments, Castronova looks at how the real and the virtual are blending through the lens of an economist.

In another advance for content creation volunteerism, LibriVox is creating and distributing audio files of public domain literature. Ranging from the Wizard of Oz to the US Constitution, Lisa was impressed by the quality of the recordings, which are voiced and recorded by volunteers who feel passionate about a particular work.

Monthly Archives: December 2005

without gods: an experiment

Just in time for the holidays, a little god-free fun…

Just in time for the holidays, a little god-free fun…

The institute is pleased to announce the launch of Without Gods, a new blog by New York University journalism professor and media historian Mitchell Stephens that will serve as a public workshop and forum for the writing of his latest book. Mitch, whose previous works include A History of News and the rise of the image the fall of the word, is in the early stages of writing a narrative history of atheism, to be published in 2007 by Carroll and Graf. The book will tell the story of the human struggle to live without gods, focusing on those individuals, “from Greek philosophers to Romantic poets to formerly Islamic novelists,” who have undertaken the cause of atheism – “a cause that promises no heavenly reward.”

Without Gods will be a place for Mitch to think out loud and begin a substantive exchange with readers. Our hope is that the conversation will be joined, that ideas will be challenged, facts corrected, queries and probes answered; that lively and intelligent discussion will ensue. As Mitch says: “We expect that the book’s acknowledgements will eventually include a number of individuals best known to me by email address.”

Without Gods is the first in a series of blogs the institute is hosting to challenge the traditional relationship between authors and readers, to learn how the network might more directly inform the usually solitary business of authorship. We are interested to see how a partial exposure of the writing process might affect the eventual finished book, and at the same time to gently undermine the notion that a book can ever be entirely finished. We invite you to read Without Gods, to spread the word, and to take part in this experiment.

wikipedia and ‘alien logic:’ the debate gets spiritual

If you like Mitchell Stephen’s book-blog about the history of atheism, you might want to compare Mitchell’s approach to that of “The Long Tail,” a book-blog written by Chris Anderson of Wired Magazine. Like Stephens, Anderson is trying to work out his ideas for a future book online: his book looks at the technology-driven atomizaton of our economy and culture, a phenomenon Anderson (and Wired) doesn’t seem particularly troubled by.

On December 18, Anderson wrote a post about what he saw as the real reason people are uncomfortable with Wikipedia: according to Anderson, we’re unable to reconcile with the “alien logic” of probabilistic and emergent systems, which produce “correct” answers on the macro-scale because “they are statistically optimized to excel over time and large numbers” — even though no one is really minding the store.

On December 18, Anderson wrote a post about what he saw as the real reason people are uncomfortable with Wikipedia: according to Anderson, we’re unable to reconcile with the “alien logic” of probabilistic and emergent systems, which produce “correct” answers on the macro-scale because “they are statistically optimized to excel over time and large numbers” — even though no one is really minding the store.

On one hand, Anderson’s been saying what I (and lots of other people) have been saying repeatedly over the past few weeks: acknowledge that sometimes Wikipedia gets things wrong, but also pay attention to the overwhelming number of times the open-source encyclopedia gets things right. At the same time, I’m not comfortable with Anderson’s suggestion that we can’t “wrap our heads around” the essential rightness of probabalistic engines — especially when he compares this to not being able to wrap our heads around probibalistic systems. This call for greater faith in the algorithm also troubles Nicholas Carr, who responds agnostically:

Maybe it’s just the Christmas season, but all this talk of omniscience and inscrutability and the insufficiency of our mammalian brains brings to mind the classic explanation for why God’s ways remain mysterious to mere mortals: “Man’s finite mind is incapable of comprehending the infinite mind of God.” Chris presents the web’s alien intelligence as something of a secular godhead, a higher power beyond human understanding… I confess: I’m an unbeliever. My mammalian mind remains mired in the earthly muck of doubt. It’s not that I think Chris is wrong about the workings of “probabilistic systems.” I’m sure he’s right. Where I have a problem is in his implicit trust that the optimization of the system, the achievement of the mathematical perfection of the macroscale, is something to be desired….Might not this statistical optimization of “value” at the macroscale be a recipe for mediocrity at the microscale – the scale, it’s worth remembering, that defines our own individual lives and the culture that surrounds us?

Carr’s point is well-taken: what is valuable about Wikipedia to many of us is not that it is an engine for self-regulation, but that it allows individual human beings to come together to create a shared knowledge resource. Anderson’s call for faith in the system is swinging the pendulum too far in the other direction: while other defenders of Wikipedia have pointed out ways to tinker with the encyclopedia’s human interface, Anderson implies that the human interface — at the individual level — doesn’t quite matter. I don’t find this particularly conforting: in fact, this idea seems much scarier than Seigenthaler’s warning that Wikipedia is a playground for “volunteer vandals.”

itp winter 2005 show

New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program recently had its Winter 2005 show. As always, the show was packed with numerous projects and visitors. Some of the work touched upon ideas we think about at the institute.

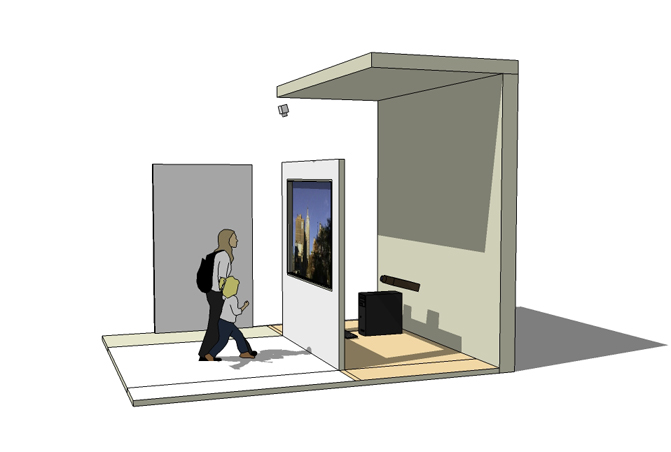

A few projects explored new ways to mediate New York. Leif Mangelsen and Jung Oh, in Time Scanned, created static panoramic images by stitching together slivers of digital video to document New York over time and space. Moving beyond the traditional guide book and map, the augmented reality project, DataCity looked at how we navigate New York. In this case, Shagun Singh, Jon Kirchherr and Saranont Limpananont proposed to layer contextual information on an interactive display system to enhance the experience of traveling through the city.

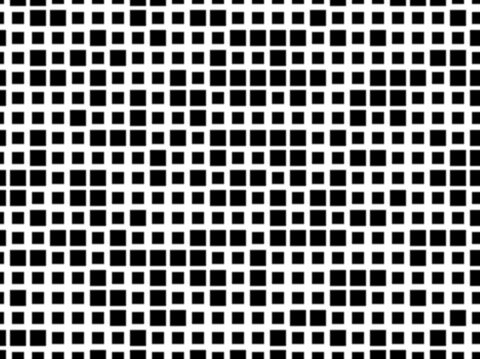

Saiyanthan Sriskandarajah created, The Wasteland, a digital representation of T.S. Eliot’s poem. Each letter is encoded into a binary format and then printed with a large format printer. The end result is an abstracted digital representation of a literary work.

Saiyanthan Sriskandarajah created, The Wasteland, a digital representation of T.S. Eliot’s poem. Each letter is encoded into a binary format and then printed with a large format printer. The end result is an abstracted digital representation of a literary work.

Joshua Knowles, Adam Asarnow, Charles Pratt, and Rocio Barcia created Itp.licio.us which was a new twist to the facebook, and explored folksonomy, privacy, and social networks by asking fellow first year students to tag each other. The successful end result (students received an average of 29.4 tags) also addressed issues of internet mediated social interaction and making public the personal information of what classmates think of others.

Although, the twice a year itp shows can be a bit of an overwhelming experience, they offer a glimpse (albeit scaled down) of emerging applications of technology which are often just around the corner for mainstream use.

the future of the book(store), circa 1899 and 2005

Leafing through an 1899 issue of the literary magazine The Dial, I came across an article called “The Distribution of Books” which resonated with the present moment at several uncanny junctures, and got me thinking about the evolving relationship between publishers, libraries, bookstores, and Google Book Search — thoughts which themselves evolved after a conversation with a writer from Pages magazine about the future of bookstores.

“The Distribution of Books” focused mainly on changes in the way books were marketed and distributed, warning that bookstores might go out of business if they failed to change their own business practices in response. “Once more the plaint of the bookseller is heard in the land,” lamented the author, “and one would be indeed stony-hearted who could view his condition without concern.”

According to “The Distribution of Books,” what should have been the privileged domain of the bookseller was being eroded at the century’s end by the book sales of “the great dealers in miscellaneous merchandise.” The article was referring to the department stores that sold books at a loss in order to lure in customers: a bit less than a century later, critics would make the same claims about Amazon, that great dealer in miscellaneous merchandise now celebrating its tenth anniversary. “The Distribution of Books” also complains of the direct marketing practices of publishers who attempted to market to readers directly. This past year, similar complaints were made after Random House joined Scholastic and Simon and Schuster this year in establishing a direct-sale online presence.

Of course, 2005 is not 1899, and this is what makes the Dial piece so startling in its familiarity: in 1899, after all, the distinction between publisher and bookseller was much fresher than now. Hybrid merchant/tradesman who printed, marketed and distributed books at the same time had been the norm for a much longer interval than the shop owner who ordered books from a variety of different publishing houses. In this sense, the publisher’s “new” practice of selling books directly was in fact a modification of bookselling practices that predated the specialized bookshop. Ultimately, the Dial piece is less about the demise of the bookseller than about the imagined demise of a relatively recent phenomenon — the specialized book seller with an investment in promoting the culture of books generally rather than the work of a specific author or publisher.

This tension between specialization and generalization also revealed itself in the article’s most indignant passage, in which the author expressed outrage over the idea that libraries might themselves get involved in bookselling. According to the Dial, bookstore owners had been subjected to:

an onslaught so unexpected and so startling it left [them] gasping for breath — [a suggestion] made a few months ago by librarian Dewey, who calmly proposed that the public libraries throughout the country should be book-selling as well as book-circulating agencies… Booksellers have always looked askance at public libraries, not understanding how they create an appetite for reading that is sure in the end to redound to the bookseller’s advantage, but their suspicious fears never anticipated the explosion in their camp of such a bombshell as this.

After delivering the “bombshell,” the author goes on to reassure the reader that Dewey’s suggestion (yes, that would be Melvil Dewey, inventor of the Dewey Decimal System) could never be taken seriously in America: such a venture on the part of the nation’s libraries would represent a socialistic entangling of the spheres of government and industry. Books sold by libraries would be sold without an eye to profit, conjectured the author, and publishing —-and perhaps the notion of the private sector itself — would collapse. “If the state or the municipality were to go into the business of selling books at cost, what should prevent it from doing the like with groceries?”

While the Dial piece made me think about the ways in which the perceived “new” threats to today’s bookstores might not be so new, it also made me consider how Dewey’s proposal might emerge in modified form in the digital era. While present-day libraries haven’t been proposing the sale of books, they certainly are planning to get into the business of marketing and distribution, as the World Digital Library attests. They are also proposing, as Librarian of Congress librarian James Billington has said, a shift toward significant partnerships with for-profit businesses which have (for various reasons) serious economic stakes in sifting through digital materials. And, as Ben noted a few weeks ago, libraries themselves have been using various strategies from online retailers to catalog and present information.

Just as libraries are starting to embrace the private sector, many bookstores are heading in the other direction: driven to the verge of extinction by poor profits, they are reinventing themselves as nonprofits that serve a valuable social and cultural function. Sure, books are still for sale, but the real “value” of a bookstore is now lies not in its merchandise, but in the intellectual or cultural community it fosters: in that respect, some bookstores are thus akin to the subscription libraries of the past.

Is it so impossible to imagine a future in which one walks into a digital distribution center, orders a latte, and uses an Amazon-type search engine to pull up the ebook that can be read at one’s reading station after the requisite number of ads have flashed on the screen? Is this a library? Is this a bookstore? Does it matter? Should it?

mass culture vs technoculture?

It’s the end of the year, and thus time for the jeremiads. In a December 18 Los Angeles Times article, Reed Johnson warns that 2005 was the year when “mass culture” — by which Johnson seemed to mean mass media generally — gave way to a consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution. According to Johnson:

It’s the end of the year, and thus time for the jeremiads. In a December 18 Los Angeles Times article, Reed Johnson warns that 2005 was the year when “mass culture” — by which Johnson seemed to mean mass media generally — gave way to a consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution. According to Johnson:

This was the year in which Hollywood, despite surging DVD and overseas sales, spent the summer brooding over its blockbuster shortage, and panic swept the newspaper biz as circulation at some large dailies went into free fall. Consumers, on the other hand, couldn’t have been more blissed out as they sampled an explosion of information outlets and entertainment options: cutting-edge music they could download off websites into their iPods and take with them to the beach or the mall; customized newcasts delivered straight to their Palm Pilots; TiVo-edited, commercial-free programs plucked from a zillion cable channels. The old mass culture suddenly looked pokey and quaint. By contrast, the emerging 21st century mass technoculture of podcasting, video blogging, the Google Zeitgeist list and “social networking software” that links people on the basis of shared interest in, say, Puerto Rican reggaeton bands seems democratic, consumer-driven, user-friendly, enlightened, opinionated, streamlined and sexy.

Or so it seems, Johnson continues: before we celebrate too much, we need to remember the difference between consumers and citizens. We are technoconsumers, not technocitizens, and as we celebrate our possibilites, we forget that “much of the supposedly independent and free-spirited techno-culture is being engineered (or rapidly acquired) by a handful of media and technology leviathans: News Corp., Apple, Microsoft, Yahoo, and Google, the budding General Motors of the Information Age.”

I hadn’t thought of Google as the GM of the Information Age. I’m not at all sure, actually, that the analogy works, given the different ways in which GM and Google leverage the US economy — fifty years hence, Google plant closures won’t be decimating middle America. But I’m very much behind Johnson’s call for more attention to media consolidation in the age of convergence. Soon, it’s going to be time for the Columbia Journalism Review to add the leviathans listed above to its Who Owns What page, which enables users to track the ownership of most old media products, but currently comes up short in tracking new media. Actually, they should consider updating it as of tomorrow, when the final details of Google’s billion dollar deal for five percent of AOL are made public.

I hadn’t thought of Google as the GM of the Information Age. I’m not at all sure, actually, that the analogy works, given the different ways in which GM and Google leverage the US economy — fifty years hence, Google plant closures won’t be decimating middle America. But I’m very much behind Johnson’s call for more attention to media consolidation in the age of convergence. Soon, it’s going to be time for the Columbia Journalism Review to add the leviathans listed above to its Who Owns What page, which enables users to track the ownership of most old media products, but currently comes up short in tracking new media. Actually, they should consider updating it as of tomorrow, when the final details of Google’s billion dollar deal for five percent of AOL are made public.

line between the real and game space… a peek into the future?

As Lisa noted in her comment to an previous post on class and gaming, the Economist reviewed the new book by Edward Castronova entitled, Synthetic Worlds : The Business and Culture of Online Games.

Castronova, also wrote an essay that was included in the Game Design Reader that was behind the “Making Games Matter” panel we attended. This essay marks the first analysis of the economics of people and their interactions in a virtual reality. Interesting to note, it has yet to be formally published in an academic economics journal.

In these studies, Castronova calculates the economics of the virtual by looking at what people are willing to pay in real currency for online gaming characters and their associated costs. As previously posted, people are making their livings in these virtual spaces by creating and selling their avatars. We are entering an era where the boundaries between the real and virtual are blurring.

Although some affluent gamers are buying their way into the higher echelons of game spaces such as EverQuest, there is still the opportunity for anyone with enough time and skill to create advanced characters. Where as in the real world, there are only a limited number of players in the NBA and CEO positions in the Fortune 500 companies. There is enough “room” in the game space to allow for many top tier characters, because the vast majority of the “normal” characters are bots run by the gaming engine.

Is the online game space the utopian society where everyone can be equal and rich and powerful? Is this a peek at the future of the real world when robots take over all the jobs that people don’t want to perform?

librivox — free public domain books read aloud by volunteers

Just read a Dec. 16th Wired article about a Canadian Hugh McGuire’s brilliant new venture Librivox. Librivox is creating and distributing free audiobooks by asking volunteers to create audio files of works of literature in the public domain. The files are hosted on the Internet Archive and are available in MP3 and OGG formats.

Thus far, Librivox — which has only been up for a few months — has recorded about 30 titles, relying on dozens of volunteers. The website promotes the project as the “acoustical liberation of the public domain” and claims that the ultimate goal is to liberate all public domain works of literature. For now, titles cataloged on the website include L Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent and the U.S. Constitution.

Thus far, Librivox — which has only been up for a few months — has recorded about 30 titles, relying on dozens of volunteers. The website promotes the project as the “acoustical liberation of the public domain” and claims that the ultimate goal is to liberate all public domain works of literature. For now, titles cataloged on the website include L Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent and the U.S. Constitution.

Using Librivox couldn’t be easier: clicking on an entry will bring you to a screen which allows you to select a Wikipedia entry on the book in question, the e-Gutenberg file of the book, an alternate Zip file of the book, and the Librivox audio version, available chapter by chapter with the names of each volunteer reader noted prominently next to the chapter information.

I listened to parts of about a half-dozen book chapters to get a sense of the quality of the recordings, and I was impressed. The volunteers have obviously chosen books they are passionate about, and the recordings are lively, quite clear and easy to listen to. As a regular audiobook listener, I was struck by the fact that while most literary audiobooks are read by authors who tend to work hard at conveying a sense of character, the Librivox selections seemed to convey, more than anything, the reader’s passion for the text itself; ie, for the written word. Here at the Institute we’ve been spending a fair amount of time trying to figure out when a book loses it’s book-ness, and I’d argue that while some audiobooks blur the boundary between book and performance, the Librivox books remind us that a book reduced to a stream of digitally produced sound can still be very much a book.

The site’s definitely worth a visit, and, if you’ve got a decent voice and a few spare hours, there’s information about how to become a volunteer reader yourself. And finally, don’t miss the list of other audiolit projects on the lower right-hand corner of the homepage: there are many voices out there, reading many books — including Japanese Classical Literature For Bedtime, if you’re so inclined.

last week: wikipedia, r kelly, gaming and google panels, and more…

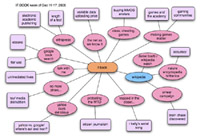

Here’s an overview of what we’ve been posting over the last week. As well, a few of us having been talking about ways to graphically represent text, so I thought I would include a mind map of this overview.

As a follow up to the increasingly controversial wikipedia front, Daniel Brandt uncovered that Brian Chase posted false information about John Seignthaler that was reported here last week. To add fuel to the fire, Nature weighed in that Encyclopedia Britannica may not be as reliable as Wikipedia.

Business Week noted a possible future of pricing for data transfer. Currently, carries such as phone and cable companies are developing technology to identify and control what types of media (voice, images, text or video) are being uploaded. This ability opens the door to being able to charge for different uses of data transfer, which would have a huge impact on uploading content for personal creative use of the internet.

Liz Barry and Bill Wetzel shared some of their experiences from their “Talk to Me” Project. With their “talk to me” sign in tow, they travel around New York and the rest of the US looking for conversation. We were impressed at how they do not have a specific agenda besides talking to people. In the mediated age, they are not motivated by external political/ religious/ documentary intentions. What they do document is available on their website, and we look forward to see what they come up with next.

The Google Book Search debate continues as well, via a panel discussion hosted by the American Bar Association. Interestingly, publishers spoke as if the wide scale use of ebooks is imminent. More importantly and even if this particular case settles out of court, the courts have a pressing need to define copyright and fair use guidelines for these emerging uses.

With the protest of the WTO meetings in Hong Kong this past week, new journalism forms took one step forward. The website Curbside @ WTO covered the meetings with submissions from journalism students, bloggers and professional journalists.

McDonalds filed a patent which suggests that it intends to offer clips of movies instead of the traditional toys in their kids oriented Happy Meals. Lisa pondered if a video clip can successfully replace a toy, and if it does, what the effects on children’s imaginations might be.

R. Kelly’s experiments in form and the “serial song” through his Trapped in the Closet recordings. While R Kelly has varying success in this endeavor, Dan compared the experience of not only the serial novel, but also Julie Powell’s foray into transferring her blog into book form and what she might have learned from R. Kelly (its hard to make unified pieces maintain an overall coherency.)

The world of academic publishing was challenged with a proposal calling to create an electronic academic press. This segment seems especially ripe for the shift to digital publishing as many journals with small circulations face raising printing and production costs.

Sol and others from the institute attended “Making Games Matter,” a panel with contributors from The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology, edited by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. The discussion covered among other things: involving the academy in creating a discourse for gaming and game design, obstacles in studying and creating games, and the game “industry” itself. The book and panel called out for games and gaming to undergo a formal study akin to the novel and the experience of reading. Also, in the gaming world, the class economics of the real and virtual began to emerge as a Chinese firm pays employees to build up characters in MMOGs to sell to affluent gamers.

off to seoul

Over the next couple of weeks I will be traveling in South Korea, the land that invented moveable type (1234), and which to this day is cooking up the future of the book on a high flame: from massivly multiplayer online games, to Samsung’s Ubiquitous Dream Hall, to the massively multiplayer citizen journalism site OhmyNews. It will take me about 20 hours to get there but I feel I’ll be stepping a few years into the future. I expect… well, I have no idea what to expect. And all this futurama is only the tip of the iceberg. I have a camera and it shouldn’t be too hard to find an internet connection, so expect a few postcards.