A split is under way in the culture industry at present, between ever more high-budget centrally-created and released products designed to net the ‘live experience’ ticket or product-buying punter, and new forms of distributed, Net-mediated creativity. This is evidenced throughout the culture industry; but while ARGs (alternate reality games) are a strong candidate for being understood as the ‘literary’ output of this new culture, there is little discussion of increasing attempts to transform this emerging genre straight into a vehicle for advertising. In the light of my own rather old-fashioned literary idealism, I want first to situate ARGs in the context of this split between culture-as-industry and culture-as-community, to argue the case for ARGs as participatory literature, and finally to ponder the appropriateness of leaving them to the mercies of the PR industry.

the culture industry and the new collaboration

Anti-pirating adverts have been common since video came into wide use. But the other day I saw one at the cinema that got me thinking. Rather than taking the line that copying media is a crime, it showed scenes from Apocalypto, while pointing out that such a spectacular film is much better enjoyed on a huge cinema screen. It struck me as a shrewd take: rather than making ominous noises about crime, the advert aimed to drive cinema attendance by foregrounding the format-specific benefits (darkened room, audience, popcorn, huge screen) of the cinema experience .

It reminded me of a conversation I had with musician-turned-intellectual Pat Kane. Since the advent of iTunes and the like, he said, gigging is often a musician’s main source of income. I had a look at live performance prices, and discovered that whereas in 2001 high-end tickets cost $60, in 2006 Paul McCartney (amongst others) charged $250 per ticket. The premium is for the format-specific features of the experience: the atmosphere, the ‘authenticity’, the transient moment. Everything else is downloadable.

But the catch is that you have to sell material that suits the ‘live’ immersive experience. That means all-singing, all-dancing extravaganza gigs (Madonna crucified on a mirrored cross in Rome, anyone?) and super-colossal epic ‘excitement’ films, full of special effects, chases, explosions and the like. Consider the top ten grossing films 2000-06: three Harry Potters, three Lord of the Ringses, three X-Men films, three Star Warses, three Matrix films, Spider-man, two Batmans, The Chronicles of Narnia, Day After Tomorrow, Jurassic Park 3, Terminator 3 and War of the Worlds. Alongside that there were typically at least two high-budget CGI films in the top ten each year Exciting fantasy epics are on the up, because if you produce anything else the punters are more likely to skip the cinema experience and just download it.

So the networked replicability of content drives a trend for high-budget, high-concept cultural content for which you can justifiably charge at the door. But other forms are on the up. The NYT just ran a story about M dot Strange, who brought a huge YouTube audience to his Sundance premiere. And December’s Wired called the LonelyGirl15 phenomenon on YouTube ‘The future of TV’. It’s not as if general cinema release is the only way to make your name. Sandi Thom‘s rise to fame through a series of webcasts tells the same story.

Here, we see artists who reverse the paradigm: rather than seeking to thrill a passive audience, they intrigue an active one. Rather than seeking to retain control, they farm parts of the story out. As Lonelygirl15’s story grows, each characer will get a vlog: rather than produce the whole thing themselves, the originators will work out a basic storyline and then pair writers and directors with actors and let them loose.

I don’t wish to argue here that this second paradigm of community-based participative creation is necessarily ‘better’, or that it will supplant existing cultural forms. But it is emerging rapidly as a major cultural force, and merits examination both in its own right and for clues to the operation of Net-native forms of literature.

fact or fiction? who cares?

A frequent characteristic of these kinds of networked co-creation is debate about the ‘reality’ of its products. LonelyGirl15 whipped up a storm on ARG Network while people tried to work out if she was an ARG trailhead, an advertising campaign, or a real teenager. Similarly, many have suspected Sandi Thom’s webcast story of including a layer of fiction. But this has not hurt Sandi’s career any more than it killed interest in LonelyGirl15. Built into these discussions is a sense that this (like much ambiguity) is not a bug but a feature, and is actually intrinsic to the operation of the net. After all, the promise underpinning Second Life, MUDs, messageboards and much of the Net’s traffic is radical self-reinvention beyond the bounds of one’s life and physical body. Fiction is part of Net reality.

Literary theorists have held fiction in special regard for thousands of years; if fiction is intrinsic to the ‘reality’ of the Net, what happens to storytellers? Is there a kind of literature native to the Net?

ARGs: net-native literature

Though it’s a relatively young phenomenon, and I have no doubt that other forms will emerge, the strongest candidates at present for consideration as such are ARGs (alternate reality games). Unlike PVP online games, they are at least partially written (textual), and rely heavily on participants’ collaboration through messageboards. If you’re trying to catch up, you essentially read the ‘story’ as it is ‘written’ by its participants in fora dedicated to solving them. They have a clear story, but are dependent for their unfolding on community participation – and may be changed by this participation: in 2001, Lockjaw ended prematurely when participants brought a class-action lawsuit against the fictional genetic engineering company at the heart of the story. Or perhaps it didnt – I’ve seen one reference to this event, but other attempts simply lead me deeper into a story that may or may not still be active.

Thus, like LonelyGirl15 and her ilk, ARGs also bridge fact and fiction. This is part of their pleasure, and it is pervasive: I had a Skype conversation yesterday with Ansuman Biswas, an artist who has been sucked into the now-unfolding MEIGEIST game when its creators referenced his work in the course of casting story clues. Ansuman delightedly sent me the link to the initial thread on the game at unfiction, where participants have been debating whether Ansuman exists or not. Even though I was talking to him at the time I almost found myself wondering, too.

Where ARGs as a creative form diverge from print literature (at least, from modern print literature) is in their use of pastiche, patchwork and mash-up. One of the delights of storytelling is the sense of an organising intelligence at work in a chaos of otherwise random events. ARGs provide this, but in a way appropriate to the Babel of content available on the Net. Participants know that someone is orchestrating a storyline, but that it will not unfold without the active contribution of the decoders, web-surfers, inveterate Googlers and avid readers tracking leads, clues, possible hints and unfolding events through the chaos of the Web. Rather than striving for that uber-modernist concept, ‘originality’, an ARG is predicated on the pre-existence of the rest of the Net, and works like a DJ with the content already present. In this, it has more in common with the magpie techniques of Montaigne (1533-92), or the copious ‘authoritative’ quotations of Chaucer than contemporary notions of the author-as-originator.

the PR money-shot

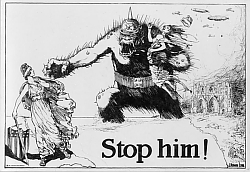

The downside of some ARG activity is the rapid incursions of the marketing machine into the format, and a corresponding tendency towards high-budget games with a PR money-shot. For example, I Love Bees turned out to be a trailer for Halo 2. This spills over into offline publication: Cathy’s Book, itself an interactive multimedia concept co-written by Sean Stewart, one of the puppetmasters of the 2001 ARG ‘The Beast, made headlines last year when it included product placements from Clinique. So where YouTube, myspace, webcasts and the like appear to be working in some ways to open up and democratise creative activity as a community activity, it is as yet unclear whether the same is true of ARGs. Is it acceptable for immersive fiction to be so seamlessly integrated with the needs of the advertising world? Is the idealism of Aristotle and Sidney still worth keeping? Or is such purism obsolete?

where are the artists?

Either way, this new genre represents, I believe, the first stirrings of a Net-native form of storytelling. ARGs have all the characteristics of networked cultural production: they unfold through the collaboration of a networked problem-solving community; they use multiple media, mixtures of fact and fiction, and a distributed reader/participant base. Their operation, and their susceptibility to co-opting by the marketing industry poses many questions; but the very nature of the form suggests that the way to address these is through engagement, not criticism. So, ultimately, this is a call for writers and artists interested in what the form is and could become: to situate Net writing in the context of why writers have always written, to explore its potential, and to ensure that it remains a form that belongs to us, rather than being sold back to us in darkened theatres with a bagful of memorabilia.

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together.

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together. If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.

If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.