There’s an interesting post by Kenneth Goldsmith at Harriet, the blog of the Poetry Foundation about writing and the Web. Kenneth Goldsmith is probably best known – or not known? – to those who read if:book as the force behind UbuWeb; there was a fascinating interview with him recently at Archinect which provides a great deal of background on his work there. He’s also an accomplished poet; see, for example, his piece Soliloquy. In his post at Harriet, Goldsmith starts with a provocative statement: “With the rise of the web, writing has met its photography.” He argues that writing needs to redefine itself for the new parameters the Web offers; it’s a provocative argument, and one that deserves to stir up a broad discussion.

Category Archives: writing

poetry in motion

I’m not sure why we didn’t note QuickMuse last year when it debuted. No matter: the concept isn’t dated and the passing year has allowed it to accrue an archive worth visiting. On the backend, QuickMuse is a project built on software by Fletcher Moore that tracks what a writer does over time; when played back, the visitor with a Javascript-enabled browser sees how the composition was written over time, sped up if desired. On the front, editor Ken Gordon has invited a number of poets to compose a poem in fifteen minutes, based, usually, on some found text. The poetry thus created isn’t necessarily the best, but that’s immaterial: it’s interesting to see how people write. (If you’d like to try this yourself, you can use Dlog.)

Composition speeds vary. Rick Moody starts writing early, making mistakes and minor corrections, but ceaselessly moving forward at a formidable clip until his fifteen minutes are up; you get the impression he could happily keep writing at the same pace for hours. The sentence “Every year South American disappears” hangs alone in Mary Jo Salter’s composition for thirty seconds; you imagine the poet turning the phrase over in her mind to find the next sentence. Lines are added, slowly, always with time passing.

What this underscores in my mind is how writing is a weirdly private act. In a sense, the reader of QuickMuse is very close to the writer, watching the poem as it unfolds; the letters appear at the exact speed at which the writer’s fingers type them in. There’s a sense of intimacy that comes with the shared time. But the thought behind the action of typing is conspicuously absent. Is the pause a pregnant moment of decision? or simply the writer not paying attention? It’s impossible to say.

time machine

The other day, a bunch of us were looking at this new feature promised for Leopard, the next iteration of the Mac operating system, and thinking about it as a possible interface for document versioning.

I’ve yet to find something that does this well. Wikis and and Google Docs give you chronological version lists. In Microsoft Word, “track changes” integrates editing history within the surface of the text, but it’s ugly and clunky. Wikipedia has a version comparison feature, which is nice, but it’s only really useful for scrutinizing two specific passages.

If a document could be seen to have layers, perhaps in a similar fashion to Apple’s Time Machine, or more like Gamer Theory‘s stacks of cards, it would immediately give the reader or writer a visual sense of how far back the text’s history goes – not so much a 3-D interface as 2.5-D. Sifting through the layers would need to be easy and tactile. You’d want ways to mark, annotate or reference specific versions, to highlight or suppress areas where text has been altered, to pull sections into a comparison view. Perhaps there could be a “fade” option for toggling between versions, slowing down the transition so you could see precisely where the text becomes liquid, the page in effect becoming a semi-transparent membrane between two versions. Or “heat maps” that highlight, through hot and cool hues, the more contested or agonized-over sections of the text (as in the Free Software Foundations commentable drafts of the GNU General Public License).

And of course you’d need to figure out comments. When the text is a moving target, which comments stay anchored to a specific version, and which ones get carried with you further through the process? What do you bring with you and what do you leave behind?

promiscuous materials

This began as a quick follow-up to my post last week on Jonathan Lethem’s recent activities in the area of copyright activism. But after a couple glasses of sake and some insomnia it mutated into something a bit bigger.

Back in March, Lethem announced that he planned to give away a free option on the film rights of his latest novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet. Interested filmmakers were invited to submit a proposal outlining their creative and financial strategies for the project, provided that they agreed to cede a small cut of proceeds if the film ends up getting distributed. To secure the option, an artist also had to agree up front to release ancillary rights to their film (and Lethem, likewise, his book) after a period of five years in order to allow others to build on the initial body of work. Many proposals were submitted and on Monday Lethem granted the project to Greg Marcks, whose work includes the feature “11:14.”

What this experiment does, and quite self-consciously, is demonstrate the curious power of the gift economy. Gift giving is fundamentally a ritual of exchange. It’s not a one-way flow (I give you this), but a rearrangement of social capital that leads, whether immediately or over time, to some sort of reciprocation (I give you this and you give me something in return). Gifts facilitate social equilibrium, creating occasions for human contact not abstracted by legal systems or contractual language. In the case of an artistic or scholarly exchange, the essence of the gift is collaboration. Or if not a direct giving from one artist to another, a matter of influence. Citations, references and shout-outs are the acknowledgment of intellectual gifts given.

By giving away the film rights, but doing it through a proposal process which brought him into conversation with other artists, Lethem purchased greater influence over the cinematic translation of his book than he would have had he simply let it go, through his publisher or agent, to the highest bidder. It’s not as if novelists and directors haven’t collaborated on film adaptations before (and through more typical legal arrangements) but this is a significant case of copyright being put to the side in order to open up artistic channels, changing what is often a business transaction — and one not necessarily even involving the author — into a passing of the creative torch.

Another Lethem experiment with gift economics is The Promiscuous Materials Project, a selection of his stories made available, for a symbolic dollar apiece, to filmmakers and dramatists to adapt or otherwise repurpose.

One point, not so much a criticism as an observation, is how experiments such as these — and you could compare Lethem’s with Cory Doctorow’s, Yochai Benkler’s or McKenzie Wark’s — are still novel (and rare) enough to serve doubly as publicity stunts. Surveying Lethem’s recent free culture experiments it’s hard not to catch a faint whiff of self-congratulation in it all. It’s oh so hip these days to align one’s self with the Creative Commons and open source culture, and with his recent foray into that arena Lethem, in his own idiosyncratic way, joins the ranks of writers shrewdly riding the wave of the Web to reinforce and even expand their old media practice. But this may be a tad cynical. I tend to think that the value of these projects as advocacy, and in a genuine sense, gifts, outweighs the self-promotion factor. And the more I read Lethem’s explanations for doing this, the more I believe in his basic integrity.

It does make me wonder, though, what it would mean for “free culture” to be the rule in our civilization and not the exception touted by a small ecstatic sect of digerati, some savvy marketers and a few dabbling converts from the literary establishment. What would it be like without the oppositional attitude and the utopian narratives, without (somewhat paradoxically when you consider the rhetoric) something to gain?

In the end, Lethem’s open materials are, as he says, promiscuities. High-concept stunts designed to throw the commodification of art into relief. Flirtations with a paradigm of culture as old as the Greek epics but also too radically new to be fully incorporated into the modern legal-literary system. Again, this is not meant as criticism. Why should Lethem throw away his livelihood when he can prosper as a traditional novelist but still fiddle at the edges of the gift economy? And doesn’t the free optioning of his novel raise the stakes to a degree that most authors wouldn’t dare risk? But it raises hypotheticals for the digital age that have come up repeatedly on this blog: what does it mean to be a writer in the infinitely reproducible non-commodifiable Web? what is the writer after intellectual property?

a new voice for copyright reform

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book, You Don’t Love Me Yet, which chronicles a struggling California rock band who, in the course of trying to compose and record a debut album, progressively lose track of who wrote their songs. Lethem has always been obsessed with laying bare his influences (he has a book of essays devoted in large part to that), but this new novel, which seems on the whole to be a slighter work than his previous two Brooklyn-based sagas, is his most direct stab to date at the complex question of originality in art.

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book, You Don’t Love Me Yet, which chronicles a struggling California rock band who, in the course of trying to compose and record a debut album, progressively lose track of who wrote their songs. Lethem has always been obsessed with laying bare his influences (he has a book of essays devoted in large part to that), but this new novel, which seems on the whole to be a slighter work than his previous two Brooklyn-based sagas, is his most direct stab to date at the complex question of originality in art.

In February Lethem published one of the better pieces that has been written lately about the adverse effects of our bloated copyright system, an essay in Harper’s entitled “The Ecstasy of Influence,” which he billed provocatively as “a plagiarism.” Lethem’s flippancy with the word is deliberate. He wants to initiate a discussion about what he sees as the ultimately paradoxical idea of owning culture. Lethem is not arguing for an abolition of copyright laws. He still wants to earn his bread as a writer. But he advocates a general relaxation of a system that has clearly grown counter to the public interest.

None of these arguments are particularly new but Lethem reposes them deftly, interweaving a diverse playlist of references and quotations from greater authorities from with the facility of a DJ. And by foregrounding the act of sampling, the essay actually enacts its central thesis: that all creativity is built on the creativity of others. We’ve talked a great deal here on if:book about the role of the writer evolving into something more like that of a curator or editor. Lethem’s essay, though hardly the first piece of writing to draw heavily from other sources, demonstrates how a curatorial method of writing does not necessarily come at the expense of a distinct authorial voice.

The Harper’s piece has made the rounds both online and off and, with the new novel, seems to have propelled Lethem, at least for the moment, into the upper ranks of copyright reform advocates. Yesterday The Washington Post ran a story on Lethem’s recent provocations. Here too is a 50-minute talk from the Authors@Google series (not surprisingly, Google is happy to lend some bandwidth to these ideas).

For some time, Cory Doctorow has been the leading voice among fiction writers for a scaling back of IP laws. It’s good now to see a novelist with more mainstream appeal stepping into the debate, with the possibility of moving it beyond the usual techno-centric channels and into the larger public sphere. I suspect Lethem’s interest will eventually move on to other things (and I don’t see him giving away free electronic versions of his books anytime soon), but for now, we’re fortunate to have his pen in the service of this cause.

of babies and bathwater

The open-sided, many-voiced nature of the Web lends itself easily to talk of free, collaborative, open-source, open-access. Suddenly a brave new world of open knowledge seems just around the corner. But understandings of how to make this world work practically for imaginative work – I mean written stories – are still in their infancy. It’s tempting to see a clash of paradigms – open-source versus proprietary content – that is threatening the fundamental terms within which all writers are encouraged to think of themselves – not to mention the established business model for survival as such.

The idea that ‘high art’ requires a business model at all has been obscured for some time (in literature at least) by a rhetoric of cultural value. This is the argument offered by many within the print publishing industry to justify its continued existence. Good work is vital to culture; it’s always the creation of a single organising consciousness; and it deserves remuneration. But the Web undermines this: if every word online is infinitely reproducible and editable, putting words in a particular order and expecting to make your living by charging access to them is considerably less effective than it was in a print universe as a model for making a living.

But while the Web erodes the opportunities to make a living as an artist producing patented content, it’s not yet clear how it proposes to feed writers who don’t copyright their work. A few are experimenting with new balances between royalty sales and other kinds of income: Cory Doctorow gives away his books online for free, and makes money of the sale of print copies. Nonfiction writers such as Chris Anderson often treat the book as a trailer for their idea, and make their actual money from consultancy and public speaking. But it’s far from clear how this could work in a widespread way for net-native content, and particularly for imaginative work.

This quality of the networked space also has implications for ideas of what constitutes ‘good work’. Ultimately, when people talk of ‘cultural value’, they usually mean the role that narratives play in shaping our sense of who and what we are. Arguably this is independent of delivery mechanisms, theories of authorship, and the practical economics of survival as an artist: it’s a function of human culture to tell stories about ourselves. And even if they end up writing chick-lit or porn to pay the bills, most writers start out recognising this and wanting to change the world through stories. But how is one to pursue this in the networked environment, where you can’t patent your words, and where collaboration is indispensable to others’ engagement with your work? What if you don’t want anyone else interfering in your story? What if others’ contributions are rubbish?

Because the truth is that some kinds of participation really don’t produce shining work. The terms on which open-source technology is beginning to make inroads into the mainstream – ie that it works – don’t hold so well for open-source writing to date. The World Without Oil ARG in some ways illustrates this problem. When I heard about the game I wrote enthusiastically about the potential I saw in it for and imaginative engagement with huge issues through a kind of distributed creativity. But Ben and I were discussing this earlier, and concluded that it’s just not working. For all I know it’s having a powerful impact on its players; but to my mind the power of stories lies in their ability to distil and heighten our sense of what’s real into an imaginative shorthand. And on that level I’ve been underwhelmed by WWO. The mass-writing experiment going on there tends less towards distillation into memorable chunks of meme and more towards a kind of issues-driven proliferation of micro-stories that’s all but abandoned the drive of narrative in favour of a rather heavy didactic exercise.

So open-sourcing your fictional world can create quality issues. Abandoning the idea of a single author can likewise leave your story a little flat. Ficlets is another experiment that foregrounds collaboration at the expense of quality. The site allows anyone to write a story of no more than (for some reason) 1,024 characters, and publish it through the site. Users can then write a prequel or sequel, and those visiting the site can rate the stories as they develop. It’s a sweetly egalitarian concept, and I’m intrigued by the idea of using Web2 ‘Hot Or Not?’ technology to drive good writing up the chart. But – perhaps because there’s not a vast amount of traffic – I find it hard to spend more than a few minutes at a time there browsing what on the whole feels like a game of Consequences, just without the joyful silliness.

In a similar vein, I’ve been involved in a collaborative writing experiment with OpenDemocracy in the last few weeks, in which a set of writers were given a theme and invited to contribute one paragraph each, in turn, to a story with a common them. It’s been interesting, but the result is sorely missing the attentions of at the very least a patient and despotic editor.

This is visible in a more extreme form in the wiki-novel experiment A Million Penguins. Ben’s already said plenty about this, so I won’t elaborate; but the attempt, in a blank wiki, to invite ‘collective intelligence’ to write a novel failed so spectacularly to create an intelligible story that there are no doubt many for whom it proves the unviability of collaborative creativity in general and, by extension, the necessity of protecting existing notions of authorship simply for the sake of culture.

So if the Web invites us to explore other methods of creating and sharing memetic code, it hasn’t figured out the right practice for creating really absorbing stuff yet. It’s likely there’s no one magic recipe; my hunch is that there’s a meta-code of social structures around collaborative writing that are emerging gradually, but that haven’t formalised yet because the space is still so young. But while a million (Linux) penguins haven’t yet written the works of Shakespeare, it’s too early to declare that participative creativity can only happen at the expense of quality .

As is doubtless plain, I’m squarely on the side of open-source, both in technological terms and in terms of memetic or cultural code. Enclosure of cultural code (archetypes, story forms, characters etc) ultimately impoverishes the creative culture as much as enclosure of software code hampers technological development. But that comes with reservations. I don’t want to see open-source creativity becoming a sweatshop for writers who can’t get published elsewhere than online, but can’t make a living from their work. Nor do I look forward with relish to a culture composed entirely of the top links on Fark, lolcats and tedious self-published doggerel, and devoid of big, powerful stories we can get our teeth into.

But though the way forwards may be a vision of the writer not as single creating consciousness but something more like a curator or editor, I haven’t yet seen anything successful emerge in this form, unless you count H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos – which was first created pre-internet. And while the open-source technology movement has evolved practices for navigating the tricky space around individual development and collective ownership, the Million Penguins debacle shows that there are far fewer practices for negotiating the relationship between individual and collective authorship of stories. They don’t teach collaborative imaginative writing in school.

Should they? The popularity of fanfic demonstrates that even if most of the fanfic fictional universes are created by one person before they are reappropriated, yet there is a demand for code that can be played with, added to, mutated and redeployed in this way. The fanfic universe is also beginning to develop interesting practices for peer-to-peer quality control. And the Web encourages this kind of activity. So how might we open-source the whole process? Is there anything that could be learned from OS coding about how to do stories in ways that acknowledge the networked, collaborative, open-sided and mutable nature of the Web?

Maybe memetic code is too different from the technical sort to let me stretch the metaphor that far. To put it another way: what social structures do writing collaborations need in order to produce great work in a way that’s both rigorous and open-sided? I think a mixture of lessons from bards, storytellers, improv theatre troupes, scriptwriting teams, open-source hacker practices, game development, Web2 business models and wiki etiquette may yet succeed in routing round the false dichotomy between proprietary quality and open-source memetic dross. And perhaps a practice developed in this way will figure out a way of enabling imaginative work (and its creators) to emerge through the Web without throwing the baby of cultural value out with the bathwater of proprietary content.

already born digital

Joan Acocella has an interesting review in The New Yorker of Darren Wershler-Henry’s recent book The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (previously discussed here on if:book). It’s worth a look just for all the juicy backstory it delivers on the typewriter as well as accounts of various writers’ intense, sometimes haunted, relationships with their machines. But Acocella also delves into an important area that apparently gets only passing consideration in the book — the way writing has changed since the advent of computers. Reading this makes you remember that with word processors we’ve all been writing “born digital” texts for quite some time:

Joan Acocella has an interesting review in The New Yorker of Darren Wershler-Henry’s recent book The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (previously discussed here on if:book). It’s worth a look just for all the juicy backstory it delivers on the typewriter as well as accounts of various writers’ intense, sometimes haunted, relationships with their machines. But Acocella also delves into an important area that apparently gets only passing consideration in the book — the way writing has changed since the advent of computers. Reading this makes you remember that with word processors we’ve all been writing “born digital” texts for quite some time:

Mallarmé spoke of the uncertainty with which we face a clean sheet of paper and try, in vain, to record our thoughts on it with some precision. As long as we were feeding paper into a typewriter, this anxiety was still present to our minds, and was revealed in the pointillism of Wite-Out, or even in the dapple of letters that were darker, pressed in confidence, as opposed to the lighter ones, pressed more hesitantly. A page produced on a manual typewriter was like a record of the torture of thought. With the P.C., the situation is altogether different. The screen, a kind of indeterminate space, does not seem violable in the same way as the page. And, because what we write on it is so effortlessly and undetectably erasable, the final text buries the evidence of our struggle, asserting that what we said was what we thought all along. Wershler-Henry suggests that the P.C.–with some help from Derrida and Baudrillard–ushered us into a world in which the difference between true and false is no longer cause for doubt or grief; falsity is taken for granted. I don’t know if he was thinking about the spurious perfection of the computer-generated page, but it would be a useful example.

Something else to think about is the effect that the computer, with its astonishing capabilities, has had on us as writers. Take just one example: the ease of moving a block of text. Highlight, hit control X, move cursor, hit control V, and, presto, that paragraph is in a new place. Of course, we were able to move things in typewritten text, too, but all that business with the scissors and the tape made us think twice, and maybe it was wise for us to hesitate before changing the order in which our brains produced our thoughts. In recent years, I have read a lot of writings that seemed to say, “This paragraph is here because it seemed an O.K. place to shove it in.” Furthermore, by allowing us to move text easily, computers influence us to write in movable units. In the novel that won Britain’s Booker Prize last year, Kiran Desai’s “The Inheritance of Loss,” there is a line space, indicating a break of thought, every three pages or so.

blooker nominees

The short list of nominees for Lulu.com’s second annual Blooker Prize, which is given to the year’s best book adapted from or based on a blog (or web comic), has been announced. This piece in the UK Times looks at how some publishers have begun more aggressively talent scouting in the blogosphere.

baudrillard and the net

Sifting through the various Baudrillard obits, I came across this passage from America, a travelogue he wrote in 1989:

…This is echoed by the other obsession: that of being ‘into’, hooked in to your own brain. What people are contemplating on their word-processor screens is the operation of their own brains. It is not entrails that we try to interpret these days, nor even hearts or facial expressions; it is, quite simply, the brain. We want to expose to view its billions of connections and watch it operating like a video-game. All this cerebral, electronic snobbery is hugely affected – far from being the sign of a superior knowledge of humanity, it is merely the mark of a simplified theory, since the human being is here reduced to the terminal excrescence of his or her spinal chord. But we should not worry too much about this: it is all much less scientific, less functional than is ordinarily thought. All that fascinates us is the spectacle of the brain and its workings. What we are wanting here is to see our thoughts unfolding before us – and this itself is a superstition.

Hence, the academic grappling with his computer, ceaselessly correcting, reworking, and complexifying, turning the exercise into a kind of interminable psychoanalysis, memorizing everything in an effort to escape the final outcome, to delay the day of reckoning of death, and that other – fatal – moment of reckoning that is writing, by forming an endless feed-back loop with the machine. This is a marvellous instrument of exoteric magic. In fact all these interactions come down in the end to endless exchanges with a machine. Just look at the child sitting in front of his computer at school; do you think he has been made interactive, opened up to the world? Child and machine have merely been joined together in an integrated circuit. As for the intellectual, he has at last found the equivalent of what the teenager gets from his stereo and his walkman: a spectacular desublimation of thought, his concepts as images on a screen.

When Baudrillard wrote this, Tim Berners-Lee and co. were writing the first pages of the WWW in Switzerland. Does the subsequent emergence of the web, the first popular networked computing medium, trump Baudrillard’s prophecy of rarified self-absorption or does this “superstition” of wanting “to see our thoughts unfolding before us,” this “interminable psychoanalysis,” simply widen into a group exercise? An obsession with being hooked into a collective brain…

I kind of felt the latter last month seeing the little phenomenon that grew up around Michael Wesch’s weirdly alluring “Web 2.0…The Machine is Us/isng Us” video (now over 1.7 million views on YouTube). The viral transmission of that clip, and the various (mostly inane) video responses it elicited, ended up feeling more like cyber-wankery than any sort of collective revelation. Then again, the form itself was interesting — a new kind of expository essay — which itself prompted some worthwhile discussion.

I think the only honest answer is that it’s both. The web both connects and insulates us, breaks down walls and provides elaborate mechanisms for self-confirmation. Change is ambiguous, and was even before we had a network connecting our machines — something that Baudrillard’s pessimism misses.

who knew?

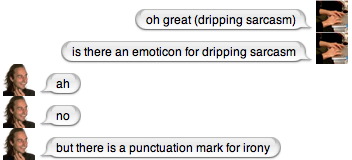

The following exchange occurred this morning during a long IM session with a close friend and colleague:

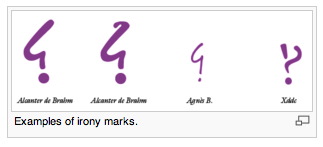

Turns out there is an actual punctuation mark in French to indicate irony which you can read about in this wikipedia article.

I don’t actually use emoticons because i find them so aesthetically uninteresting, so i love the idea of a new class of punctuation marks evolving to take the place of the smiley face in all its saccharine implementations.