In the first ‘Books and the man’ post I took the example of Alexander Pope to argue that the idea of ‘high’ literature is inseparable from economic conditions that enable a writer to turn himself into a brand and sell copyrighted material to his readership. In this post I want to look at what happens to creative work in a medium whose very nature militates against copyright.

The internet encourages artists to give stuff away for free, and to capitalise (somehow) on abundance and reproducibility. Ben’s recent roundup of copyright-related readings quotes Jeff Jarvis to this effect: “It has taken 13 years of internet history for media companies to learn that, to give up the idea that they control something scarce they can charge consumers for.” So the answer, says Jay Rosen, is advertising: “Advertising tied to search means open gates for all users”. But while this works just fine for regularly-updated information-type content, how are works of imagination to be funded? As media professor Tim Jackson pointed out some years ago in Towards A New Media Aesthetic, the infinite reproducibility of content on the web threatens the livelihood of artists and writers to a degree that critics such as Keen believe will bring about the collapse of civilization as we know it.

Keen’s wrong. There were artists before there was copyright, and there will be afterwards. Leaving aside my speculations about experiments such as Meta-Markets, cultural forms are starting to emerge online that make use of the internet’s mutability, endlessness, unreliability and infinitely-reproducible nature. But they’re not ‘high art’, in the sense that Pope pioneered. Rather, they hark back to an earlier period of literature when aristocratic patronage was the norm, and there was little distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art except in the sense of being calibrated to the tastes of the target audience.

I’ve written here previously about the ways in which alternate reality gaming is the first genuinely net-native storytelling form. I complained that this exciting form was emerging and was already being colonised by the advertising industry, through sponsorship and similar. Where and how, I wondered, would the ‘independent’ ARGs emerge?

I’d like to eat my words. Calling for ‘independent’ ARGs invoked the perspective of those cultural assumptions of ‘independence’ that both created and were created by the scarcity business model of copyright. In doing so, I ignored the fact that the internet doesn’t use a scarcity model – and hence that the concept of ‘independence’ doesn’t work in the same way. And internet users don’t seem to care that much about it.

I asked Perplex City creator Dan Hon whether he thought there was a bias, or any qualitative difference, between ‘independent’ and sponsored ARGs. He told me that ARG enthusiasts don’t reall care: “It’s normally the execution of the game that will have the most impact.”

So for enthusiasts of the internet’s first native storytelling form, the issue of whether corporate sponsorship is acceptable (an idea which would beanathema to anyone raised in the modernist tradition of authorship) is completely meaningless. If anything, Dan reckons ‘independence’ counts against you: “There absolutely isn’t any value-laden bias towards indie-ARGs – in fact, if anything there’s a negative bias against them. Many players […] are quite happy to give warnings that the indie args are liable to spontaneously implode just because the people behind them are “too indie”. A quick nose around the ‘ARGs with Potential’ section on the Unfiction boards turns up enough ‘This looks like a dodgy indie affair’ style remarks to back up this statement.

So while the arts world “was divided between shock and hilarity” when Fay Weldon got jewellers Bulgari to pay an undisclosed amount for frequent mentions in a 2001 novel, there are no anxieties in the ARG community about seeing advertising converge with the arts. Perhaps one could argue that ARGers are typically computer gaming enthusiasts too, and if they can cope with expensive Playstation games they can cope with Playstation-sponsored stories.

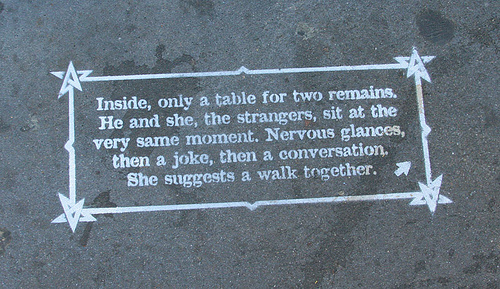

But. Take a look at Where Are The Joneses?, a collaboratively-written, professionally-filmed and Creative Commons-licenced online sitcom devised by former Channel 4 new media schemer David Bausola. Not an ARG; but a near-perfect instance of bottom-up culture. Written by its community, quality-checked by the production team, funny, absorbing, released on open licence – and an advert for Ford Motors.

If you catch him in an expansive mood, David will tell you that the marketing industry will survive only if it stops trying to influence culture and just starts making it. The flip side of that is that vested interests will, increasingly, explicitly find their way into creative works produced online. And, in my view, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

A glance at some of the scions of the pre-eighteenth-century canon gives a hint at the role that aristocratic patronage played in the arts. To hear some of the anti-internet rearguard speak, one might think that To Penshurst was written independently of the relation between Sir Robert Sidney and Ben Jonson; one might think that the arts has always been unsullied by power; that the encroachment of the the latter (in the form of commerce) on the former is a sign of our imminent cultural disintegration.

But contrary to Keen’s assertion that the mechanisms of copyright are indispensable to cultural dynamism, the English cultural renaissance that gave us Shakespeare, Bacon, Sidney, Donne, Marvell et al was largely driven by aristocratic patronage. Copyright hadn’t been invented yet. And if the world of art and culture is to survive in a post-copyright environment, it may be time to look furthe back in the past than the eighteenth century, and re-examine previous models. Which means looking again at patronage, which in turn, today, makes a strong case for embracing the advert. With the distinctions between brand patronage and creative culture already collapsing, it may be time for artists to wake up to the power they could wield by embracing and negotiating with the vested interests of corporate sponsors. If they do, the result may yet be a digital Renaissance.

We are proud to announce that the brilliant media scholar and critic

We are proud to announce that the brilliant media scholar and critic