If you like Mitchell Stephen’s book-blog about the history of atheism, you might want to compare Mitchell’s approach to that of “The Long Tail,” a book-blog written by Chris Anderson of Wired Magazine. Like Stephens, Anderson is trying to work out his ideas for a future book online: his book looks at the technology-driven atomizaton of our economy and culture, a phenomenon Anderson (and Wired) doesn’t seem particularly troubled by.

On December 18, Anderson wrote a post about what he saw as the real reason people are uncomfortable with Wikipedia: according to Anderson, we’re unable to reconcile with the “alien logic” of probabilistic and emergent systems, which produce “correct” answers on the macro-scale because “they are statistically optimized to excel over time and large numbers” — even though no one is really minding the store.

On December 18, Anderson wrote a post about what he saw as the real reason people are uncomfortable with Wikipedia: according to Anderson, we’re unable to reconcile with the “alien logic” of probabilistic and emergent systems, which produce “correct” answers on the macro-scale because “they are statistically optimized to excel over time and large numbers” — even though no one is really minding the store.

On one hand, Anderson’s been saying what I (and lots of other people) have been saying repeatedly over the past few weeks: acknowledge that sometimes Wikipedia gets things wrong, but also pay attention to the overwhelming number of times the open-source encyclopedia gets things right. At the same time, I’m not comfortable with Anderson’s suggestion that we can’t “wrap our heads around” the essential rightness of probabalistic engines — especially when he compares this to not being able to wrap our heads around probibalistic systems. This call for greater faith in the algorithm also troubles Nicholas Carr, who responds agnostically:

Maybe it’s just the Christmas season, but all this talk of omniscience and inscrutability and the insufficiency of our mammalian brains brings to mind the classic explanation for why God’s ways remain mysterious to mere mortals: “Man’s finite mind is incapable of comprehending the infinite mind of God.” Chris presents the web’s alien intelligence as something of a secular godhead, a higher power beyond human understanding… I confess: I’m an unbeliever. My mammalian mind remains mired in the earthly muck of doubt. It’s not that I think Chris is wrong about the workings of “probabilistic systems.” I’m sure he’s right. Where I have a problem is in his implicit trust that the optimization of the system, the achievement of the mathematical perfection of the macroscale, is something to be desired….Might not this statistical optimization of “value” at the macroscale be a recipe for mediocrity at the microscale – the scale, it’s worth remembering, that defines our own individual lives and the culture that surrounds us?

Carr’s point is well-taken: what is valuable about Wikipedia to many of us is not that it is an engine for self-regulation, but that it allows individual human beings to come together to create a shared knowledge resource. Anderson’s call for faith in the system is swinging the pendulum too far in the other direction: while other defenders of Wikipedia have pointed out ways to tinker with the encyclopedia’s human interface, Anderson implies that the human interface — at the individual level — doesn’t quite matter. I don’t find this particularly conforting: in fact, this idea seems much scarier than Seigenthaler’s warning that Wikipedia is a playground for “volunteer vandals.”

Category Archives: wikipedia

last week: wikipedia, r kelly, gaming and google panels, and more…

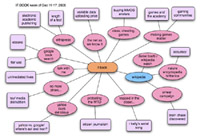

Here’s an overview of what we’ve been posting over the last week. As well, a few of us having been talking about ways to graphically represent text, so I thought I would include a mind map of this overview.

As a follow up to the increasingly controversial wikipedia front, Daniel Brandt uncovered that Brian Chase posted false information about John Seignthaler that was reported here last week. To add fuel to the fire, Nature weighed in that Encyclopedia Britannica may not be as reliable as Wikipedia.

Business Week noted a possible future of pricing for data transfer. Currently, carries such as phone and cable companies are developing technology to identify and control what types of media (voice, images, text or video) are being uploaded. This ability opens the door to being able to charge for different uses of data transfer, which would have a huge impact on uploading content for personal creative use of the internet.

Liz Barry and Bill Wetzel shared some of their experiences from their “Talk to Me” Project. With their “talk to me” sign in tow, they travel around New York and the rest of the US looking for conversation. We were impressed at how they do not have a specific agenda besides talking to people. In the mediated age, they are not motivated by external political/ religious/ documentary intentions. What they do document is available on their website, and we look forward to see what they come up with next.

The Google Book Search debate continues as well, via a panel discussion hosted by the American Bar Association. Interestingly, publishers spoke as if the wide scale use of ebooks is imminent. More importantly and even if this particular case settles out of court, the courts have a pressing need to define copyright and fair use guidelines for these emerging uses.

With the protest of the WTO meetings in Hong Kong this past week, new journalism forms took one step forward. The website Curbside @ WTO covered the meetings with submissions from journalism students, bloggers and professional journalists.

McDonalds filed a patent which suggests that it intends to offer clips of movies instead of the traditional toys in their kids oriented Happy Meals. Lisa pondered if a video clip can successfully replace a toy, and if it does, what the effects on children’s imaginations might be.

R. Kelly’s experiments in form and the “serial song” through his Trapped in the Closet recordings. While R Kelly has varying success in this endeavor, Dan compared the experience of not only the serial novel, but also Julie Powell’s foray into transferring her blog into book form and what she might have learned from R. Kelly (its hard to make unified pieces maintain an overall coherency.)

The world of academic publishing was challenged with a proposal calling to create an electronic academic press. This segment seems especially ripe for the shift to digital publishing as many journals with small circulations face raising printing and production costs.

Sol and others from the institute attended “Making Games Matter,” a panel with contributors from The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology, edited by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. The discussion covered among other things: involving the academy in creating a discourse for gaming and game design, obstacles in studying and creating games, and the game “industry” itself. The book and panel called out for games and gaming to undergo a formal study akin to the novel and the experience of reading. Also, in the gaming world, the class economics of the real and virtual began to emerge as a Chinese firm pays employees to build up characters in MMOGs to sell to affluent gamers.

watching wikipedia watch

In an interview in CNET today, Daniel Brandt of Wikipedia Watch — the man who tracked down Brian Chase, the author of the false biography of John Seigenthaler on Wikipedia — details the process he used to track Chase down. I found it an interesting reality check on the idea of online anonymity. I was also a bit nonplussed by the fact that Brandt created a phony identity for himself in order to discover who had created a fake version of the real Seigenthaler. According to Brandt:

All I had was the IP address and the date and timestamp, and the various databases said it was a BellSouth DSL account in Nashville. I started playing with the search engines and using different tools to try to see if I could find out more about that IP address. They wouldn’t respond to trace router pings, which means that they were blocked at a firewall, probably at BellSouth…But very strangely, there was a server on the IP address. You almost never see that, since at most companies, your browsers and your servers are on different IP addresses. Only a very small company that didn’t know what it was doing would have that kind of arrangement. I put in the IP address directly, and then it comes back and said, “Welcome to Rush Delivery.” It didn’t occur to me for about 30 minutes that maybe that was the name of a business in Nashville. Sure enough they had a one-page Web site. So the next day I sent them a fax. [they didn’t respond, and] The next night, I got the idea of sending a phony e-mail, I mean an e-mail under a phony name, phony account. When they responded, sure enough, the originating IP address matched the one that was in Seigenthaler’s column.

Overall, I’m still having mixed feelings about Brandt’s “bust” of Brian Chase — mostly because of the way the event has skewed discussion of Wikipedia, but partly because Chase’s outing seems to have damaged the hapless-seeming Chase much more than Seigenthaler had been damaged by the initial fake post. The CNET interview suggests that Brandt might also have some regrets about the fallout over Chase, though Brandt frames his concern as yet another critique of Wikipedia. Brandt claims he is uncomfortable about the fact that Chase has a Wikipedia biography, since “when this poor guy is trying to send out his resume,” employers will google him, find the Wikipedia entry, and refuse to hire him: since Wikipedia entries are not as ephemeral as news articles, he adds, the entry is actually “an invasion of privacy even more than getting your name in the newspaper.” This seems to be an odd bit of reasoning, since Brandt, after all, was the one who made Chase notorious.

When asked by the CNET interviewer how he would “fix” Wikipedia, Brandt maintained an emphasis on the idea that biographical entries are Wikipedia’s Achilles heel, an belief which is tied, perhaps, to his own reasons for taking Wikipedia to task — a prominent draft resister in the 1960s, Brandt discovered that his own Wikipedia post had links he considered unflattering. He explained to CNET that his first priority would be to “freeze” biographies on the site which had been checked for accuracy:

I would go and take all the biographical articles on living persons and take them out of the publicly editable Wikipedia and put them in a sandbox that’s only open to registered users. That keeps out all spiders and scrapers. And then you work on all these biographies and get them up to snuff and then put them back in the main Wikipedia for public access but lock them so they cannot be edited. If you need to add more information, you go through the process again. I know that’s a drastic change in ideology because Wikipedia’s ideology says that the more tweaks you get from the masses, the better and better the article gets and that quantity leads to improved quality irrevocably. Their position is that the Seigenthaler thing just slipped through the crack. Well, I don’t buy that because they don’t know how many other Seigenthaler situations are lurking out there.

“Seigenthaler situations.” This term could either come in to use as a term to refer to the dubious accuracy of an online post — or, alternately, to refer to a phobic response to open-source knowledge construction. Time will tell.

Meanwhile, in the pro-Wikipedia world, an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education today notes that a group of Wikipedia fans have decided to try to create a Wikiversity, a learning center based on Wiki open-source principles. According to the Chronicle, “It’s not clear exactly how extensive Wikiversity would be. Some think it should serve only as a repository for educational materials; others think it should also play host to online courses; and still others want it to offer degrees.” I’m curious to see if anything like a Wikiversity could get off the group, and how it will address the tension around open-source knowledge that been foregrounded by the Wikipedia-bashing that has taken place over the past few weeks.

Finally, there’s a great defense of Wikipedia in Danah Boyd’s Apophenia. Among other things, Boyd writes:

We should be teaching our students how to interpret the materials they get on the web, not banning them from it. We should be correcting inaccuracies that we find rather than protesting the system. We have the knowledge to be able to do this, but all too often, we’re acting like elitist children. In this way, i believe academics are more likely to lose credibility than Wikipedia.

nature magazine says wikipedia about as accurate as encyclopedia brittanica

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did something similar, though less formal, a couple of months back — read the first comment). According to an article published today:

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did something similar, though less formal, a couple of months back — read the first comment). According to an article published today:

Entries were chosen from the websites of Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica on a broad range of scientific disciplines and sent to a relevant expert for peer review. Each reviewer examined the entry on a single subject from the two encyclopaedias; they were not told which article came from which encyclopaedia. A total of 42 usable reviews were returned out of 50 sent out, and were then examined by Nature’s news team. Only eight serious errors, such as misinterpretations of important concepts, were detected in the pairs of articles reviewed, four from each encyclopaedia. But reviewers also found many factual errors, omissions or misleading statements: 162 and 123 in Wikipedia and Britannica, respectively.

It’s interesting to see Nature coming to the defense of Wikipedia at the same time that so many academics in the humanities and social science have spoken out against it: it suggests that the open source culture of academic science has led to a greater tolerance for Wikipedia in the scientific community. Nature’s reviewers were not entirely thrilled with Wikipidia: for example, they found the Britannica articles to be much more well-written and readable. But they also noted that Britannica’s chief problem is the time and effort it takes for the editorial department to update material as a scientific field evolves or changes: Wikipedia updates often occur practically in real time.

One not-so-suprising fact unearthed by Nature’s staffers is that the scientific community contained about twice as many Wikipedia users as Wikipedia authors. The best way to ensure that the science in Wikipedia is sound, the magazine argued, is for scientists to commit to writing about what they know.

wikipedia update: author of seigenthaler smear confesses

According to a Dec 11 New York Times article, Daniel Brandt, a book indexer who runs the site Wikipedia Watch, helped to flush out the man who posted the false biography of USA Today and Freedom Forum founder John Seigenthaler on Wikipedia. After Brandt discovered the post issued from a small delivery company in Nashville, the man in question — 38-year-old Brian Chase — sent a letter of apology to Seigenthaler and resigned from his job as operations manager at the company.

According to the Times, Chase claims that he didn’t realize that Wikipedia was used as a serious research tool: he posted the information to shock a co-worker who was familiar with the Seigenthaler family. Seigenthaler, who complained in a USA Today editorial last week about the protections afforded to the “volunteer vandals” who post anonymously in cyberspace, told the New York Times that he would not seek damages from Chase.

Responding to the fallout from Seigenthaler’s USA Today editorial, Wikipedia founder James Wales changed Wikipedia’s policies so that posters now must all be registered with Wikipedia. But, as Brandt shows, it’s takes work to remain anonymous in cyberspace. Though I’m not sure that I beleive Chase’s professed astonishment that anyone would take his post seriously (why else would it shock his co-worker?), it seems clear that he didn’t think what he was doing so outrageous that he ought to make a serious effort to hide his tracks.

Meanwhile, Wales has become somewhat irked by Seignthaler’s continuing attacks on Wikipedia. Posting to the threaded discussion of the issue on the mailing list of the Association for Internet Researchers, Wikipedia’s founder expressed exasperation about Seigenthaler’s telling the Associated Press this morning that “Wikipedia is inviting [more regulation of the internet] by its allowing irresponsible vandals to write anything they want about anybody.” Wales wrote:

*sigh* Facts about our policies on vandalism are not hard to come by. A statement like Seigenthaler’s, a statement that is egregiously false, would not last long at all at Wikipedia.

For the record, it is just absurd to say that Wikipedia allows “irresponsible vandals to write anything they want about anybody.”

–Jimbo

where we’ve been, where we’re going

This past week at if:book we’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between this weblog and the work we do. We decided that while if:book has done a fine job reflecting and provoking the conversations we have at the Institute, we wanted to make sure that it also seems as coherent to our readers as it does to us. With that in mind, we’ve decided to begin posting a weekly roundup of our blog posts, in which we synthesize (as much a possible) what we’ve been thinking and talking about from Monday to Friday.

So here goes. This week we spent a lot of time reflecting on simulation and virtuality. In part, this reflection grew out of our collective reading of a Tom Zengotita’s book Mediated, which discusses (among other things) the link between alienation from the “real” through digital mediation and increased solipsism. Bob seemed especially interested in the dialectic relationship between, on one hand, the opportunity for access afforded by ever-more sophisticated form of simulation, and, on the other, the sense that something must be lost when as the encounter with the “real” recedes entirely.

This, in turn, led to further conversation about what we might think of as the “loss of the real” in the transition from books on paper to books on a computer screen. On one hand, there seems to be a tremendous amount of anxiety that Google Book Search might somehow make actual books irrelevant and thus destroy reading and writing practices linked to the bound book. On the other hand, one could take the position of Cory Doctorow that books as objects are overrated, and challenge the idea that a book needs to be digitally embodied to be “real.”

As the debate over Google Book Search continually reminds us, one of the most challenging things in sifting through discussions of emerging media forms is learning to tell the difference between nostalgia and useful critical insight. Often the two are hopelessly intertwined; in this week’s debates about Wikipedia, for example, discussion of how to make the open-source encyclopedia more useful was often tempered by the suggestion that encyclopedias of the past were always be superior to Wikipedia, an assertion easily challenged by a quick browse through some old encyclopedias.

Finally, I want to mention that we finally got around to setting up a del.icio.us account. There will be a formal link on the blog up soon, but you can take a look now. It will expand quickly.

more on wikipedia

As summarized by a Dec. 5 article in CNET, last week was a tough one for Wikipedia — on Wednesday, a USA today editorial by John Seigenthaler called Wikipedia “irresponsible” for not catching significant mistakes in his biography, and Thursday, the Wikipedia community got up in arms after discovering that former MTV VJ and longtime podcaster Adam Curry had edited out references to other podcasters in an article about the medium.

In response to the hullabaloo, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales now plans to bar anonymous users from creating new articles. The change, which went into effect today, could possibly prevent a repeat of the Seigenthaler debacle; now that Wikipedia would have a record of who posted what, presumably people might be less likely to post potentially libelous material. According to Wales, almost all users who post to Wikipedia are already registered users, so this won’t represent a major change to Wikipedia in practice. Whether or not this is the beginning of a series of changes to Wikipedia that push it away from its “hive mind” origins remains to be seen.

I’ve been surprised at the amount of Wikipedia-bashing that’s occurred over the past few days. In a historical moment when there’s so much distortion of “official” information, there’s something peculiar about this sudden outrage over the unreliability of an open-source information system. Mostly, the conversation seems to have shifted how people think about Wikipedia. Once an information resource developed by and for “us,” it’s now an unreliable threat to the idea of truth imposed on us by an unholy alliance between “volunteer vandals” (Seigenthaler’s phrase) and the outlaw Jimmy Wales. This shift is exemplified by the post that begins a discussion of Wikipedia that took place over the past several days on the Association of Internet Researchers list serve. The scholar who posted suggested that researchers boycott Wikipedia and prohibit their students from using the site as well until Wikipedia develops “an appropriate way to monitor contributions.” In response, another poster noted that rather than boycotting Wikipedia, it might be better to monitor for the site — or better still, write for it.

Another comment worthy of consideration from that same discussion: in a post to the same AOIR listserve, Paul Jones notes that in the 1960s World Book Encyclopedia, RCA employees wrote the entry on television — scarcely mentioning television pioneer Philo Farnsworth, longtime nemesis of RCA. “Wikipedia’s failing are part of a public debate,” Jones writes, “Such was not the case with World Book to my knowledge.” In this regard, the flak over Wikipedia might be considered a good thing: at least it gives those concerned with the construction of facts the opportunity to debate with the issue. I’m just not sure that making Wikipedia the enemy contributes that much to the debate.

the next dictionary

I found this Hartford Courant article on slashdot.

Martin Benjamin heads up an eleven year old project to create an online Swahili dictionary called the Kamusi Project. Despite 80 million speakers, the current Swahili dictionary is over 30 years old. Setting this project apart from other online dictionaries, these entries are created by, not only academics, but also by volunteers ranging from former Peace Corp workers to African linguistic hobbyists. The site also includes a discussion board for the community of users and developers.

It is also important to mention that, like wikipedia, donations and volunteers support this collaborative project. Unlike wikipedia, it does not have the broad audience and publicity that wikipedia enjoys, which makes funding a continual issue.

wikipedia hard copy

Believe it or not, they’re printing out Wikipedia, or rather, sections of it. Books for the developing world. Funny that just days ago Gary remarked:

“A Better Wikipedia will require a print version…. A print version would, for better or worse, establish Wikipedia as a cosmology of information and as a work presenting a state of knowledge.”

Prescient.

a better wikipedia will require a better conversation

There’s an interesting discussion going on right now under Kim’s Wikibooks post about how an open source model might be made to work for the creation of authoritative knowledge — textbooks, encyclopedias etc. A couple of weeks ago there was some dicussion here about an article that, among other things, took some rather cheap shots at Wikipedia, quoting (very selectively) a couple of shoddy passages. Clearly, the wide-open model of Wikipedia presents some problems, but considering the advantages it presents (at least in potential) — never out of date, interconnected, universally accessible, bringing in voices from the margins — critics are wrong to dismiss it out of hand. Holding up specific passages for critique is like shooting fish in a barrel. Even Wikipedia’s directors admit that most of the content right now is of middling quality, some of it downright awful. It doesn’t then follow to say that the whole project is bunk. That’s a bit like expelling an entire kindergarten for poor spelling. Wikipedia is at an early stage of development. Things take time.

Instead we should be talking about possible directions in which it might go, and how it might be improved. Dan for one, is concerned about the market (excerpted from comments):

What I worry about…is that we’re tearing down the old hierarchies and leaving a vacuum in their wake…. The problem with this sort of vacuum, I think, is that capitalism tends to swoop in, simply because there are more resources on that side….

…I’m not entirely sure if the world of knowledge functions analogously, but Wikipedia does presume the same sort of tabula rasa. The world’s not flat: it tilts precariously if you’ve got the cash. There’s something in the back of my mind that suspects that Wikipedia’s not protected against this – it’s kind of in the state right now that the Web as a whole was in 1995 before the corporate world had discovered it. If Wikipedia follows the model of the web, capitalism will be sweeping in shortly.

Unless… the experts swoop in first. Wikipedia is part of a foundation, so it’s not exactly just bobbing in the open seas waiting to be swept away. If enough academics and librarians started knocking on the door saying, hey, we’d like to participate, then perhaps Wikipedia (and Wikibooks) would kick up to the next level. Inevitably, these newcomers would insist on setting up some new vetting mechanisms and a few useful hierarchies that would help ensure quality. What would these be? That’s exactly the kind of thing we should be discussing.

The Guardian ran a nice piece earlier this week in which they asked several “experts” to evaluate a Wikipedia article on their particular subject. They all more or less agreed that, while what’s up there is not insubstantial, there’s still a long way to go. The biggest challenge then, it seems to me, is to get these sorts of folks to give Wikipedia more than just a passing glance. To actually get them involved.

For this to really work, however, another group needs to get involved: the users. That might sound strange, since millions of people write, edit and use Wikipedia, but I would venture that most are not willing to rely on it as a bedrock source. No doubt, it’s incredibly useful to get a basic sense of a subject. Bloggers (including this one) link to it all the time — it’s like the conversational equivalent of a reference work. And for certain subjects, like computer technology and pop culture, it’s actually pretty solid. But that hits on the problem right there. Wikipedia, even at its best, has not gained the confidence of the general reader. And though the Wikimaniacs would be loathe to admit it, this probably has something to do with its core philosophy.

Karen G. Schneider, a librarian who has done a lot of thinking about these questions, puts it nicely:

Wikipedia has a tagline on its main page: “the free-content encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” That’s an intriguing revelation. What are the selling points of Wikipedia? It’s free (free is good, whether you mean no-cost or freely-accessible). That’s an idea librarians can connect with; in this country alone we’ve spent over a century connecting people with ideas.

However, the rest of the tagline demonstrates a problem with Wikipedia. Marketing this tool as a resource “anyone can edit” is a pitch oriented at its creators and maintainers, not the broader world of users. It’s the opposite of Ranganathan’s First Law, “books are for use.” Ranganathan wasn’t writing in the abstract; he was referring to a tendency in some people to fetishize the information source itself and lose sight that ultimately, information does not exist to please and amuse its creators or curators; as a common good, information can only be assessed in context of the needs of its users.

I think we are all in need of a good Wikipedia, since in the long run it might be all we’ve got. And I’m in now way opposed to its spirit of openness and transparency (I think the preservation of version histories is a fascinating element and one which should be explored further — perhaps the encyclopedia of the future can encompass multiple versions of the “the truth”). But that exhilarating throwing open of the doors should be tempered with caution and with an embrace of the parts of the old system that work. Not everything need be thrown away in our rush to explore the new. Some people know more than other people. Some editors have better judgement than others. There is such a thing as a good kind of gatekeeping.

If these two impulses could be brought into constructive dialogue then we might get somewhere. This is exactly the kind of conversation the Wikimedia Foundation should be trying to foster.