Stacy Schiff takes a long, hard look at Wikipedia in a thoughtful essay in the latest New Yorker. She begins with a little historical perspective on encyclopedias, fitting Wikipedia into a distinguished, centuries-long lineage of subversion that includes, most famously, the Encyclopédie of 1780, composed by leading French philosophes of the day such as Diderot, Rousseau and Voltaire. Far from being the crusty, conservative genre we generally take it to be, the encyclopedia has long served as an arena for the redeployment of knowledge power:

Stacy Schiff takes a long, hard look at Wikipedia in a thoughtful essay in the latest New Yorker. She begins with a little historical perspective on encyclopedias, fitting Wikipedia into a distinguished, centuries-long lineage of subversion that includes, most famously, the Encyclopédie of 1780, composed by leading French philosophes of the day such as Diderot, Rousseau and Voltaire. Far from being the crusty, conservative genre we generally take it to be, the encyclopedia has long served as an arena for the redeployment of knowledge power:

In its seminal Western incarnation, the encyclopedia had been a dangerous book. The Encyclopédie muscled aside religious institutions and orthodoxies to install human reason at the center of the universe–and, for that muscling, briefly earned the book’s publisher a place in the Bastille. As the historian Robert Darnton pointed out, the entry in the Encyclopédie on cannibalism ends with the cross-reference “See Eucharist.”

But the dust kicked up by revolution eventually settles. Heir to the radical Encyclopédie are the stolid, dependable reference works we have today, like Britannica, geared not at provoking questions, but at providing trustworthy answers.

Wikipedia’s radicalism is its wresting of authority away from the established venues — away from the very secular humanist elite that produced works like the Encyclopédie and sparked the Enlightenment. Away from these and toward a new networked class of amateur knowledge workers. The question, then, and this is the question we should all be asking, especially Wikipedia’s advocates, is where does this latest revolution point? Will this relocation of knowledge production away from accredited experts to volunteer collectives — collectives that aspire no less toward expertise, but in the aggregate performance rather than as individuals — lead to a new enlightening, or to a dark, muddled decline?

Or both? All great ideas contain their opposites. Reason, the flame at the heart of the Enlightenment, contained, as Max Horkheimer famously explained, the seeds of its own descent into modern, mechanistic barbarism. The open source movement, applied first to software, and now, through Wikipedia, to public knowledge, could just as easily descend into a morass of ignorance and distortion, especially as new economies rise up around collaborative peer production and begin to alter the incentives for participation. But it also could be leading us somewhere more vital than our received cultural forms — more vital and better suited to help us confront the ills of our time, many of them the result of the unbridled advance of that glorious 18th century culture of reason, science and progress that shot the Encyclopédie like a cork out of a bottle of radical spirits.

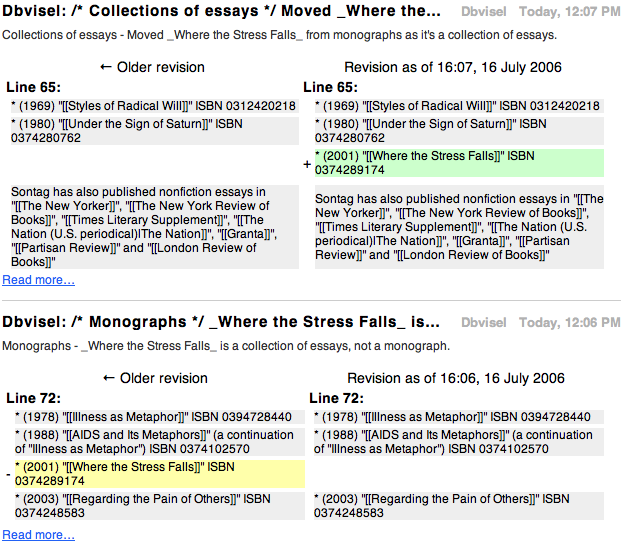

Which is all the more reason that we should learn how to read Wikipedia in the fullest way: by exploring the discussion pages and revision histories that contextualize each article, and to get involved ourselves as writers and editors. Take a look at the page on global warming, and then pop over to its editorial discussion, with over a dozen archived pages going back to December, 2001. Dense as hell, full of struggle. Observe how this new technology, the Internet, through the dynamics of social networks and easy publishing tools, enables a truer instance of that most Enlightenment of ideas: a reading public.

All of which led me to ponder an obvious but crucial notion: that a book’s power is derived not solely from its ideas and language, but also from the nature of its production — how and by whom it is produced, our awareness of that process, and our understanding of where the work as a whole stands within the contemporary arena of ideology and politics. It’s true, Britannica and its ilk are descendants of a powerful reordering of human knowledge, but they have become an established order of their own. What Wikipedia does is tap a long-mounting impulse toward a new reordering. Schiff quotes Charles Van Doren, who served as an editor at Britannica:

Because the world is radically new, the ideal encyclopedia should be radical, too…. It should stop being safe–in politics, in philosophy, in science.

The accuracy of this or that article is not what is at issue here, but rather the method by which the articles are written, and what that tells us. Wikipedia is a personal reeducation, a medium that is its own message. To roam its pages is to be in contact, whether directly or subliminally, with a powerful new idea of how information gets made. And it’s far from safe.

Where this takes us is unclear. In the end, after having explored many of the possible dangers, Schiff acknowledges, in a lovely closing paragraph, that the change is occurring whether we like it or not. Moreover, she implies — and this is really important — that the technology itself is not the cause, but simply an agent interacting with preexisting social forces. What exactly those forces are — that’s something to discuss.

As was the Encyclopédie, Wikipedia is a combination of manifesto and reference work. Peer review, the mainstream media, and government agencies have landed us in a ditch. Not only are we impatient with the authorities but we are in a mood to talk back. Wikipedia offers endless opportunities for self-expression. It is the love child of reading groups and chat rooms, a second home for anyone who has written an Amazon review. This is not the first time that encyclopedia-makers have snatched control from an élite, or cast a harsh light on certitude. Jimmy Wales may or may not be the new Henry Ford, yet he has sent us tooling down the interstate, with but a squint back at the railroad. We’re on the open road now, without conductors and timetables. We’re free to chart our own course, also free to get gloriously, recklessly lost.

There was something of a valedictory feeling around Wikimania yesterday, springing perhaps from Jimmy Wales’s plenary talk: the feeling that a magnificent edifice had been constructed, and all that remained was to convince people to actually use it. If we build it, they will come & figure it out. Wales declared that it was time to stop focusing on quantity in Wikipedia and to start focusing on quality: Wikipedia has pages for just about everything that needs a page, although many of the pages aren’t very good. I won’t disagree with that, but there’s something else that needs to happen: the negotiation involved as their new technology increasingly hits the rest of the world.

There was something of a valedictory feeling around Wikimania yesterday, springing perhaps from Jimmy Wales’s plenary talk: the feeling that a magnificent edifice had been constructed, and all that remained was to convince people to actually use it. If we build it, they will come & figure it out. Wales declared that it was time to stop focusing on quantity in Wikipedia and to start focusing on quality: Wikipedia has pages for just about everything that needs a page, although many of the pages aren’t very good. I won’t disagree with that, but there’s something else that needs to happen: the negotiation involved as their new technology increasingly hits the rest of the world.

It’s interesting to track how the mainstream media covers the big, sprawling story that is Wikipedia.

It’s interesting to track how the mainstream media covers the big, sprawling story that is Wikipedia.