![]() Another funny thing about Larry Sanger’s idea of a progressive fork off of Wikipedia is that he can do nothing, under the terms of the Free Documentation License, to prevent his expert-improved content from being reabsorbed by Wikipedia. In other words, the better the Citizendium becomes, the better Wikipedia becomes — but not vice versa. In the Citizendium (the name still refuses to roll off the tongue), forks are definitive. The moment a new edit is made, an article’s course is forever re-charted away from Wikipedia. So, assuming anything substantial comes of the Citizendium, feeding well-checked, better written content to Wikipedia could end up being its real value. But would it be able to sustain itself under such uninspiring circumstances? The result might be that the experts themselves fork back as well.

Another funny thing about Larry Sanger’s idea of a progressive fork off of Wikipedia is that he can do nothing, under the terms of the Free Documentation License, to prevent his expert-improved content from being reabsorbed by Wikipedia. In other words, the better the Citizendium becomes, the better Wikipedia becomes — but not vice versa. In the Citizendium (the name still refuses to roll off the tongue), forks are definitive. The moment a new edit is made, an article’s course is forever re-charted away from Wikipedia. So, assuming anything substantial comes of the Citizendium, feeding well-checked, better written content to Wikipedia could end up being its real value. But would it be able to sustain itself under such uninspiring circumstances? The result might be that the experts themselves fork back as well.

Category Archives: wikipedia

a fork in the road II: shirky on citizendium

Clay Shirky has some interesting thoughts on why Larry Sanger’s expert-driven Wikipedia spinoff Citizendium is bound to fail. At the heart of it is Sanger’s notion of expertise, which is based largely on institutional warrants like academic credentials, yet lacks in Citizendium the institutional framework to effectively impose itself. In other words, experts are “social facts” that rely on culturally manufactured perceptions and deferences, which may not be transferrable to an online project like the Citizendium. Sanger envisions a kind of romance between benevolent academics and an adoring public that feels privileged to take part in a distributed apprenticeship. In reality, Shirky says, this hybrid of Wikipedia-style community and top-down editorial enforcement is likely to collapse under its own contradictions. Shirky:

Citizendium is based less on a system of supportable governance than on the belief that such governance will not be necessary, except in rare cases. Real experts will self-certify; rank-and-file participants will be delighted to work alongside them; when disputes arise, the expert view will prevail; and all of this will proceed under a process that is lightweight and harmonious. All of this will come to naught when the citizens rankle at the reflexive deference to editors; in reaction, they will debauch self-certification…contest expert preogatives, rasing the cost of review to unsupportable levels…take to distributed protest…or simply opt-out.

Shirky makes a point at the end of his essay that I found especially insightful. He compares the “mechanisms of deference” at work in Wikipedia and in the proposed Citizendium. In other words, how in these two systems does consensus crystallize around an editorial action? What makes people say, ok, I defer to that?

The philosophical issue here is one of deference. Citizendium is intended to improve on Wikipedia by adding a mechanism for deference, but Wikipedia already has a mechanism for deference — survival of edits. I recently re-wrote the conceptual recipe for a Menger Sponge, and my edits have survived, so far. The community has deferred not to me, but to my contribution, and that deference is both negative (not edited so far) and provisional (can always be edited.)

Deference, on Citizendium will be for people, not contributions, and will rely on external credentials, a priori certification, and institutional enforcement. Deference, on Wikipedia, is for contributions, not people, and relies on behavior on Wikipedia itself, post hoc examination, and peer-review. Sanger believes that Wikipedia goes too far in its disrespect of experts; what killed Nupedia and will kill Citizendium is that they won’t go far enough.

My only big problem with this piece is that it’s too easy on Wikipedia. Shirky’s primary interest is social software, so the big question for him is whether a system will foster group interaction — Wikipedia’s has proven to do so, and there’s reason to believe that Citizendium’s will not, fair enough. But Shirky doesn’t acknowledge the fact that Wikipedia suffers from some of the same problems that he claims will inevitably plague Citizendium, the most obvious being insularity. Like it or not, there is in Wikipedia de facto top-down control by self-appointed experts: the cliquish inner core of editors that over time has becomes increasingly hard to penetrate. It’s not part of Wikipedia’s policy, it certainly goes against the spirit of the enterprise, but it exists nonetheless. These may not be experts as defined by Sanger, but they certainly are “social facts” within the Wikipedia culture, and they’ve even devised semi-formal credential systems like barnstars to adorn their user profiles and perhaps cow more novice users. I still agree with Shirky’s overall prognosis, but it’s worth thinking about some of the problems that Sanger is trying to address, albeit in a misconceived way.

a fork in the road for wikipedia

Estranged Wikipedia cofounder Larry Sanger has long argued for a more privileged place for experts in the Wikipedia community. Now his dream may finally be realized. A few days ago, he announced a new encyclopedia project that will begin as a “progressive fork” off of the current Wikipedia. Under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, anyone is free to reproduce and alter content from Wikipedia on an independent site as long as the new version is made available under those same terms. Like its antecedent, the new Citizendium, or “Citizens’ Compendium”, will rely on volunteers to write and develop articles, but under the direction of self-nominated expert subject editors. Sanger, who currently is in the process of recruiting startup editors and assembling an advisory board, says a beta of the site should be up by the end of the month.

We want the wiki project to be as self-managing as possible. We do not want editors to be selected by a committee, which process is too open to abuse and politics in a radically open and global project like this one is. Instead, we will be posting a list of credentials suitable for editorship. (We have not constructed this list yet, but we will post a draft in the next few weeks. A Ph.D. will be neither necessary nor sufficient for editorship.) Contributors may then look at the list and make the judgment themselves whether, essentially, their CVs qualify them as editors. They may then go to the wiki, place a link to their CV on their user page, and declare themselves to be editors. Since this declaration must be made publicly on the wiki, and credentials must be verifiable online via links on user pages, it will be very easy for the community to spot false claims to editorship.

We will also no doubt need a process where people who do not have the credentials are allowed to become editors, and where (in unusual cases) people who have the credentials are removed as editors. (link)

Initially, this process will be coordinated by “an ad hoc committee of interim chief subject editors.” Eventually, more permanent subject editors will be selected through some as yet to be determined process.

Another big departure from Wikipedia: all authors and editors must be registered under their real name.

More soon…

Reports in Ars Technica and The Register.

wikipedia-britannica debate

The Wall Street Journal the other day hosted an email debate between Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales and Encyclopedia Britannica editor-in-chief Dale Hoiberg. Irreconcilible differences, not surprisingly, were in evidence. ![]()

![]() But one thing that was mentioned, which I had somehow missed recently, was a new governance experiment just embarked upon by the German Wikipedia that could dramatically reduce vandalism, though some say at serious cost to Wikipedia’s openness. In the new system, live pages will no longer be instantaneously editable except by users who have been registered on the site for a certain (as yet unspecified) length of time, “and who, therefore, [have] passed a threshold of trustworthiness” (CNET). All edits will still be logged, but they won’t be reflected on the live page until that version has been approved as “non-vandalized” by more senior administrators. One upshot of the new German policy is that Wikipedia’s front page, which has long been completely closed to instantaneous editing, has effectively been reopened, at least for these “trusted” users.

But one thing that was mentioned, which I had somehow missed recently, was a new governance experiment just embarked upon by the German Wikipedia that could dramatically reduce vandalism, though some say at serious cost to Wikipedia’s openness. In the new system, live pages will no longer be instantaneously editable except by users who have been registered on the site for a certain (as yet unspecified) length of time, “and who, therefore, [have] passed a threshold of trustworthiness” (CNET). All edits will still be logged, but they won’t be reflected on the live page until that version has been approved as “non-vandalized” by more senior administrators. One upshot of the new German policy is that Wikipedia’s front page, which has long been completely closed to instantaneous editing, has effectively been reopened, at least for these “trusted” users.

In general, I believe that these sorts of governance measures are a sign not of a creeping conservatism, but of the growing maturity of Wikipedia. But it’s a slippery slope. In the WSJ debate, Wales repeatedly assails the elitism of Britannica’s closed editorial model. But over time, Wikipedia could easily find itself drifting in that direction, with a steadily hardening core of overseers exerting ever tighter control. Of course, even if every single edit were moderated, it would still be quite a different animal from Britannica, but Wales and his council of Wikimedians shouldn’t stray too far from what made Wikipedia work in the first place, and from what makes it so interesting.

In a way, the exchange of barbs in the Wales-Hoiberg debate conceals a strange magnetic pull between their respective endeavors. Though increasingly seen as the dinosaur, Britannica has made small but not insignificant moves toward openess and currency on its website (Hoiberg describes some of these changes in the exchange), while Wikipedia is to a certain extent trying to domesticate itself in order to attain the holy grail of respectability that Britannica has long held. Think what you will about Britannica’s long-term prospects, but it’s a mistake to see this as a clear-cut story of violent succession, of Wikipedia steamrolling Britannica into obsolescence. It’s more interesting to observe the subtle ways in which the two encyclopedias cause each other to evolve.

Wales certainly has a vision of openness, but he also wants to publish the world’s best encyclopedia, and this includes releasing something that more closely resembles a Britannica. Back in 2003, Wales proposed the idea of culling Wikipedia’s best articles to produce a sort of canonical version, a Wikipedia 1.0, that could be distributed on discs and printed out across the world. Versions 1.1, 1.2, 2.0 etc. would eventually follow. This is a perfectly good idea, but it shouldn’t be confused with the goals of the live site. I’m not saying that the “non-vandalized” measure was constructed specifically to prepare Wikipedia for a more “authoritative” print edition, but the trains of thought seem to have crossed. Marking versions of articles as non-vandalized, or distinguishing them in other ways, is a good thing to explore, but not at the expense of openness at the top layer. It’s that openness, crazy as it may still seem, that has lured millions into this weird and wonderful collective labor.

on business models in web publishing

Here at the Institute, we’re generally more interested in thinking up new forms of publishing than in figuring out how to monetize them. But one naturally perks up at news of big money being made from stuff given away for free. Doc Searls points to a few items of such news.

First, that latest iteration of the American dream: blogging for big bucks, or, the self-made media mogul. Yes, a few have managed to do it, though I don’t think they should be taken as anything more than the exceptions that prove the rule that most blogs are smaller scale efforts in an ecology of niches, where success is non-monetary and more of the “nanofame” variety that iMomus, David Weinberger and others have talked about (where everyone is famous to fifteen people). But there is that dazzling handful of popular bloggers that rival the mass media outlets, and they’re raking in tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars in ad revenues.

Some sites mentioned in the article:

— TechCrunch: “$60,000 in ad revenue every month” (not surprising — its right column devoted to sponsors is one of the widest I’ve seen)

— Boing Boing: “on track to gross an estimated $1 million in ad revenue this year”

— paidContent.org: over a million a year

— Fark.com: “on pace to become a multimillion-dollar property.

Then, somewhat surprisingly, is The New York Times. Handily avoiding the debacle predicted a year ago by snarky bloggers like myself when the paper decided to relocate its op-ed columnists and other distinctive content behind a pay wall, the Times has pulled in $9 million from nearly 200,000 web-exclusive Times Select subscribers, while revenues from the Times-owned About.com continue to skyrocket. There’s a feeling at the company that they’ve struck a winning formula (for now) and will see how long they can ride it:

When I ask if TimesSelect has been successful enough to suggest that more material be placed behind the wall, Nisenholtz [senior vice president for digital operations] replies, “The strategy isn’t to move more content from the free site to the pay site; we need inventory to sell to advertisers. The strategy is to create a more robust TimesSelect” by using revenue from the service to pay for more unique content. “We think we have the right formula going,” he says. “We don’t want to screw it up.”

***Subsequent thought: I’m not so sure. Initial indicators may be good, but I still think that the pay wall is a ticket to irrelevance for the Times’ columnists. Their readership is large and (for now) devoted enough to maintain the modestly profitable fortress model, but I think we’ll see it wither over time.***

Also, in the Times, there’s this piece about ad-supported wiki hosting sites like Wikia, Wetpaint, PBwiki or the swiftly expanding WikiHow, a Wikipedia-inspired how-to manual written and edited by volunteers. Whether or not the for-profit model is ultimately compatible with the wiki work ethic remains to be seen. If it’s just discrete ads in the margins that support the enterprise, then contributors can still feel to a significant extent that these are communal projects. But encroach further and people might begin to think twice about devoting their time and energy.

***Subsequent thought 2: Jesse made an observation that makes me wonder again whether the Times Company’s present success (in its present framework) may turn out to be short-lived. These wiki hosting networks are essentially outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing” as the latest jargon goes, the work of the hired About.com guides. Time will tell which is ultimately the more sustainable model, and which one will produce the better resource. Given what I’ve seen on About.com, I’d place my bets on the wikis. The problem? You, or your community, never completely own your site, so you’re locked into amateur status. With Wikipedia, that’s the point. But can a legacy media company co-opt so many freelancers without pay? These are drastically different models. We’re probably not dealing with an either/or here.***

We’ve frequently been asked about the commercial potential of our projects — how, for instance, something like GAM3R 7H30RY might be made to make money. The answer is we don’t quite know, though it should be said that all of our publishing experiments have led to unexpected, if modest, benefits — bordering on the financial — for their authors. These range from Alex selling some of his paintings to interested commenters at IT IN place, to Mitch gradually building up a devoted readership for his next book at Without Gods while still toiling away at the first chapter, to McKenzie securing a publishing deal with Harvard within days of the Chronicle of Higher Ed. piece profiling GAM3R 7H30RY (GAM3R 7H30RY version 1.2 will be out this spring, in print).

Build up the networks, keep them open and toll-free, and unforseen opportunities may arise. It’s long worked this way in print culture too. Most authors aren’t making a living off the sale of their books. Writing the book is more often an entree into a larger conversation — from the ivory tower to the talk show circuit, and all points in between. With the web, however, we’re beginning to see the funnel reversed: having the conversation leads to writing the book. At least in some cases. At this point it’s hard to trace what feeds into what. So many overlapping conversations. So many overlapping economies.

wikipedia thread

There’s a really interesting post and related comments on KairosNews about the addition of an administrative layer to Wikipedia.

notable wikipedians

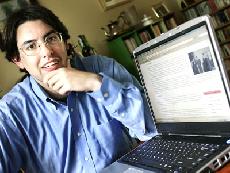

Simon Pulsifer: “the king of Wikipedia”

“He lives at home and doesn’t have a girlfriend.”

(photo: Bill Grimshaw/The Globe and Mail)

I just came across this story in The Toronto Globe and Mail about a young man from Ottawa by the name of Simon Pulsifer who, under the moniker SimonP, is Wikipedia’s most prolific contributor: “with 78,000 entries edited and 2,000 to 3,000 new articles to his name. He can’t remember the exact number.”

Pulsifer is also the subject of an article in Wikipedia, which, like many of the vanity stubs devoted to the encyclopedia’s editors, was nominated for deletion, only to be voted a keeper after some discussion. Justin Hall, a colleague of ours at USC, often cited as the first blogger, and a distinguished Wikipedian in his own right, offered the following in defense of the Pulsifer page:

As Wikipedia grows in importance and global reach, the most passionate participants in this collective editing experiment become important global intellectuals. Simon Pulsifer is one of the first public Wikipedians – with a great number of articles, a passion for editing under-developed subjects, and a strong sense of the mission of Wikipedia. He might not care to have an article about him here, but already mainstream media outlets (a Canadian newspaper) and online news sites (digg.com) have saluted his work. That attention and importance is only likely to increase. Let’s keep this article because Simon Pulsifer has already reached a greater number of people than many of the “historic” individuals described on Wikipedia.

Both Pulsifer and Hall are members of what could be considered the Wikipedia elite, the “notable Wikipedians“. Many of these probably deserve a good share of the credit for Wikipedia’s success. Now, though, I’m more interested in how Wikipedia’s corps of editors might gradually expand to include a greater slice of the public: teacher, students, and people from all walks of life.

Zealous Wikipedia hobbyists like Pulsifer, god love ’em, will hopefully, over time, be considered the exceptions that prove the general rule of participation: editing as a more modest pursuit that one builds into one’s intellectual life and lifelong learning regimen. If enough people begin to take part in this way, Wikipedia could become more diverse, more exhaustive, and more accurate than it already is. The Pulsifers and Halls might end up being its governors, its civil servants, its politicians. Of course, it is the process that is most important: the kind of civic participation and engagement over points of dissent that collaborating on Wikipedia entails. Bob explained this eloquently last week. Or, as Pulsifer describes it:

You write an article and you think you’ve made it as good as it can be and then you put it out there for everyone to see and edit. And within just a few minutes, you have started a dialogue over how best to represent a subject.

the trouble with wikis in china

I’ve just been reading about this Chinese online encyclopedia, modeled after Wikipedia, called “e-Wiki,” which last month was taken offline by its owner under pressure from the PRC government. Reporters Without Borders and The Sydney Morning Herald report that it was articles on Taiwan and the Falun Gong (more specifically, an article on an activist named James Lung with some connection to FG) that flagged e-Wiki for the censors.

Baidu: the heavy paw of the state.

Meanwhile, “Baidupedia,” the user-written encyclopedia run by leading Chinese search engine Baidu is thriving, with well over 300,000 articles created since its launch in April. Of course, “Baidu Baike,” as the site is properly called, is heavily censored, with all edits reviewed by invisible behind-the-scenes administrators before being published.

Wikipedia’s article on Baidu Baike points out the following: “Although the earlier test version was named ‘Baidu WIKI’, the current version and official media releases say the system is not a wiki system.” Which all makes sense: to an authoritarian, wikis, or anything that puts that much control over information in the hands of the masses, is anathema. Indeed, though I can’t read Chinese, looking through it, pages on Baidu Baike do not appear to have the customary “edit” links alongside sections of text. Rather, there’s a text entry field at the bottom of the page with what seems to be a submit button. There’s a big difference between a system in which edits are submitted for moderation and a totally open system where changes have to be managed, in the open, by the users themselves.

All of which underscores how astonishingly functional Wikipedia is despite its seeming vulnerability to chaotic forces. Wikipedia truly is a collectively owned space. Seeing how China is dealing with wikis, or at least, with their most visible cultural deployment, the collective building of so-called “reliable knowledge,” or encyclopedias, underscores the political implications of this oddly named class of web pages.

Dan, still reeling from three days of Wikimania, as well as other meetings concerning MIT’s One Laptop Per Child initiative, relayed the fact that the word processing software being bundled into the 100-dollar laptops will all be wiki-based, putting the focus on student collaboration over mesh networks. This may not sound like such a big deal, but just take a moment to ponder the implications of having all class writing assignments being carried out wikis. The different sorts of skills and attitudes that collaborating on everything might nurture. There a million things that could go wrong with the One Laptop Per Child project, but you can’t accuse its developers of lacking bold ideas about education.

But back to the Chinese. An odd thing remarked on the talk page of the Wikipedia article is that Baidu Baike actually has an article about Wikipedia that includes more or less truthful information about Wikipedia’s blockage by the Great Firewall in October ’05, as well as other reasonably accurate, and even positive, descriptions of the site. Wikipedia contributor Miborovsky notes:

Interestingly enough, it does a decent explanation of WP:NPOV (Wikipedia’s Neutral Point of View policy) and paints Wikipedia in a positive light, saying “its activities precisely reflects the web-culture’s pluralism, openness, democractic values and anti-authoritarianism.”

But look for Wikipedia on Baidu’s search engine (or on Google, Yahoo and MSN’s Chinese sites for that matter) and you’ll get nothing. And there’s no e-Wiki to be found.

jaron lanier’s essay on “the hazards of the new online collectivism”

In late May John Brockman’s Edge website published an essay by Jaron Lanier — “Digital Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism”. Lanier’s essay caused quite a flurry of comment both pro and con. Recently someone interested in the work of the Institute asked me my opinion. I thought that in light of Dan’s reportage from the Wikimania conference in Cambridge i would share my thoughts about Jaron’s critique of Wikipedia . . .

I read the article the day it was first posted on The Edge and thought it so significant and so wrong that I wrote Jaron asking if the Institute could publish a version in a form similar to Gamer Theory that would enable readers to comment on specific passages as well as on the whole. Jaron referred me to John Brockman (publisher of The Edge), who although he acknowledged the request never got back to us with an answer.

From my perspective there are two main problems with Jaron’s outlook.

a) Jaron misunderstands the Wikipedia. In a traditional encyclopedia, experts write articles that are permanently encased in authoritative editions. The writing and editing goes on behind the scenes, effectively hiding the process that produces the published article. The standalone nature of print encyclopedias also means that any discussion about articles is essentially private and hidden from collective view. The Wikipedia is a quite different sort of publication, which frankly needs to be read in a new way. Jaron focuses on the “finished piece”, ie. the latest version of a Wikipedia article. In fact what is most illuminative is the back-and-forth that occurs between a topic’s many author/editors. I think there is a lot to be learned by studying the points of dissent; indeed the “truth” is likely to be found in the interstices, where different points of view collide. Network-authored works need to be read in a new way that allows one to focus on the process as well as the end product.

b) At its core, Jaron’s piece defends the traditional role of the independent author, particularly the hierarchy that renders readers as passive recipients of an author’s wisdom. Jaron is fundamentally resistant to the new emerging sense of the author as moderator — someone able to marshal “the wisdom of the network.”

I also think it is interesting that Jaron titles his article Digital Maoism, with which he hopes to tar the Wikipedia with the brush of bottom-up collectivism. My guess is that Jaron is unaware of Mao’s famous quote: “truth emerges in the course of struggle [around ideas]”. Indeed, what I prize most about the Wikipedia is that it acknowledges the messiness of knowledge and the process by which useful knowledge and wisdom accrete over time.

wikimania: the importance of naming things

I’ll write up what happened on the second day of Wikimania soon – I saw a lot of talks about education – but a quick observation for now. Brewster Kahle delivered a speech after lunch entitled “Universal Access to All Knowledge”, detailing his plans to archive just about everything ever & the various issues he’s confronted along the way, not least Jack Valenti. Kahle learned from Valenti: it’s important to frame the terms of the debate. Valenti explained filesharing by declaring that it was Artists vs. Pirates, an obscuring dichotomy, but one that keeps popping up. Kahle was happy that he’d succeeded in creating a catch phrase in naming “orphan works” – a term no less loaded – before the partisans of copyright could.

I’ll write up what happened on the second day of Wikimania soon – I saw a lot of talks about education – but a quick observation for now. Brewster Kahle delivered a speech after lunch entitled “Universal Access to All Knowledge”, detailing his plans to archive just about everything ever & the various issues he’s confronted along the way, not least Jack Valenti. Kahle learned from Valenti: it’s important to frame the terms of the debate. Valenti explained filesharing by declaring that it was Artists vs. Pirates, an obscuring dichotomy, but one that keeps popping up. Kahle was happy that he’d succeeded in creating a catch phrase in naming “orphan works” – a term no less loaded – before the partisans of copyright could.

Wikimania is dominated by Wikipedia, but it’s not completely about Wikipedia – it’s about wikis more generally, of which Wikipedia is by far the largest. There are people here using wikis to do immensely different things – create travel guides, create repositories of lesson plans for K–12 teachers, using wikis for the State Department’s repositories of information. Many of these are built using MediaWiki, the software that runs Wikipedia, but not all by any means. All sorts of different platforms have been made to create websites that can be edited by users. All of these fall under the rubric “wiki”. we could just as accurately refer to wikis as “collaboratively written websites”, the least common denominator of all of these sites. I’d argue that the word has something to do with the success of the model: nobody would feel any sense of kinship about making “collaboratively written websites” – that’s a nebulous concept – but when you slap the name “wiki” on it, you have something easily understood, a form about which people can become fanatical.