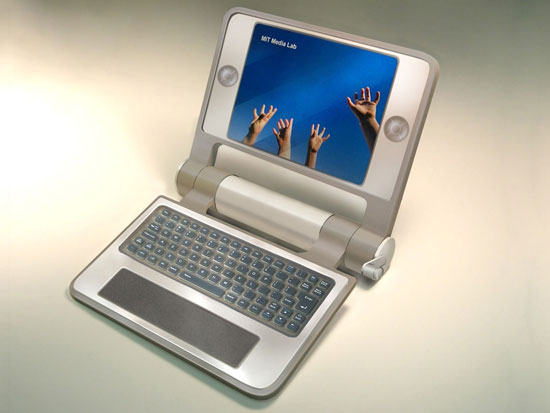

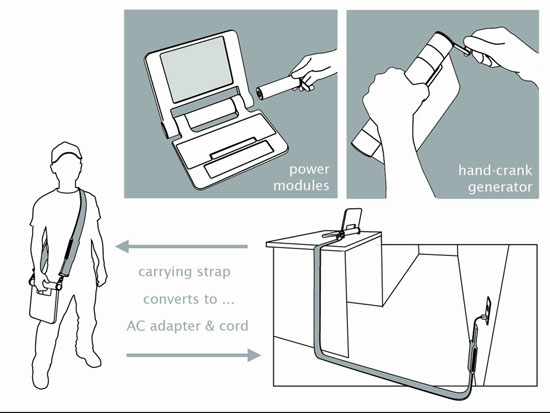

MIT has released some new images of its $100 laptop prototype, of which it hopes to have 5 to 15 million test units within the year. The laptops are much more durable than your average commercial machine, can be used as writing tablets or rotated 90 degrees as ebooks, and run on Linux – 100% free software. The idea is for the machines to provide a platform for an open source education movement throughout the South – a major hack of the current global order.

I love the hand cranks on the side, a backup charging option for remote or poorly provided areas where there is little or no electricity.

(“The $100 laptop moves closer to reality” in CNET)

Category Archives: technology

the future of the institute

lately i’ve been thinking about how the institute for the future of the book should be experimental in form as well as content – an organization whose work, when appropriate, is carried out in real time in a relatively public forum. one of the key themes of our first year has been the way a network adds value to an enterprise, whether that be a thought experiment, an attempt to create a collective memory, a curated archive of best practices, or a blog that gathers and processes the world around it. i sense we are feeling our way to new methods of organizing work and distributing the results, and i want to figure out ways to make that aspect of our effort more transparent, more available to the world. this probably calls for a reevaluation of (or a re-acquaintance with) our idea of what an institute actually is, or should be.

the university-based institute arose in the age of print. scholars gathering together to make headway in a particular area of inquiry wrote papers, edited journals, held symposia and printed books of the proceedings. if books are what humans have used to move big ideas around, institutes arose to focus attention on particular big ideas and to distribute the result of that attention, mostly via print. now, as the medium shifts from printed page to networked screen, the organization and methods of “institutes” will change as well.

how they will change is what we hope to find out, and in some small way, influence. so over the next year or so we’ll be trying out a variety of different approaches to presenting our work, and new ways of facilitating debate and discussion. hopefully, we’ll draw some of you in along the way.

here’s a first try. we’ve decided (see thinking out loud) to initiate a weekly discussion at the institute where we read a book (or article or….) and then have a no-holds discussion about it — hoping to at least begin to understand some of the first order questions about what we are doing and how it fits into our perspectives on society. mostly we’re hoping to get to a place where we are regularly asking these questions in our work (whether designing software, studying the web, holding a symposium, or encouraging new publishing projects), measuring technological developments against a sense of what kind of society we’d like to live in and how a particular technology might help or hinder our getting there.

the first discussion is focused on neil postman’s “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century.” following is the audio we recorded broken into annotated chapters. we would be interested in getting people’s feedback on both form and content. (jump to the discussion)

podcast: discussing neil postman’s “building a bridge to the 18th century”

(Annotated audio recordings of this discussion appear further down.)

(Annotated audio recordings of this discussion appear further down.)

On the dedication page of “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century,” Neil Postman quotes the poet Randall Jarrell:

Soon we shall know everything the 18th century didn’t know, and nothing it did, and it will be hard to live with us.

Though often failing to provide satisfying answers, Postman asks the kind of first-order questions one hears all too infrequently at a time when technology’s impact on our social, political and intellectual lives grows ever more profound. Postman has been accused of deep reactionism toward technology, and indeed, his hostility toward computers and telecommunications betrays an elitism that discredits some of his larger, and quite compelling observations.

In spite of this, Postman’s diagnosis is persuasive: that the idea of technological progress bequeathed by the Enlightenment has detached from reason and become a runaway train, that we are unquestioningly embracing new technologies that unleash massive change on our family and communal life, our democracy, and our capacity to think critically. We have stopped asking the single most important question that should be applied to all new technological innovations: does this technology solve a problem? If so, then at what cost? To whose benefit? And at whose expense?

Postman portrays the contemporary West as a culture without a narrative, littered with the shards of broken ideologies – depressed, unmotivated, and therefore uncritical of the new technologies that are foisted upon it by a rapacious capitalist system. The culprit, as he sees it, is postmodernism, which he lambasts (rather simplistically) as a corrosive intellectual trend, picking at the corpse of the Enlightenment, and instilling torpor and malaise at all levels of culture through its distrust of language and dogged refusal to accept one truth over another. This kind of thinking, Postman argues, is seductive, but it starves humans of their inspiration and sense of purpose.

To be saved, he goes on, and to build a better future, we would do well to look back to the philosophes of 18th century Europe, who, in the face of surging industrialization, defined a new idea of universal rational humanism – one that allowed for various interpretations within its fold, was rigorously suspicious of religious or any other kind of dogma, and yet gave the world a sense of moral uplift and progress. Postman does not suggest that we copy the 18th century, but rather give it careful study in order to draw inspiration for a new positive narrative, and for a reinvigoration of our critical outlook. This, Postman insists, offers us the best chance of surviving our future.

Postman’s note of alarm, if at times shrill, is nonetheless a refreshing antidote to the techno-optimism that pervades contemporary culture. And his recognition of our “crisis in narrative” – a formulation borrowed from Vaclav Havel – is dead on.

September 19: Bob, Dan, Kim, and Ben discuss Postman’s book at our new Brooklyn office (special prize if you pick out the sound of the ice cream truck passing by).

1. Bob’s preface – thoughts about how we do business at the institute (1:56) (download)

2. Ben’s first impressions – childhood under threat… Dan’s first impressions into discussion – a Clinton-era book, sets up a rather straw man caricature with the postmodernists, but society’s need for a narrative is compelling – why the Christian right has done so well… Postman seems to be assuming that progress is a law, that there is a directed narrative to history – problems with how he treats evolution. (6:43) (download)

3. Bob: Postman is much better at identifying problems than at coming up with solutions. Which is what makes him compelling. His stance is courageous. People assume with technology that just because something can be done it should be done. This is a tremendous problem – an affliction. If you could go back in time and be the inventor of the automobile, would you do it? People get angry at the responsibility this question imputes to them. How can we put these big questions at the center of our work? (13:34) (download)

4. Another big question… “An electronic community is only a simulation of a real community”? Flickr, Friendster, Howard Dean campaign? What is the vehicle for talking about this? What format is best for engaging these questions? Looking for new forms that illuminate or activate the questions. (15:43) (download)

5. Where/who are the public intellectuals today? [The ice cream truck passes by.] Strange bifurcation of the intellectual elite – many of the best-educated people most able to deal with abstraction make their living producing popular media that controls society. (10:07) (download)

6. Is capitalism the problem? Postman’s bias: written language will never be surpassed in its power to deal with abstract thought and cultivation of ideas. But we are arguably past the primacy of print. What is our attitude toward this? (9:39) (download)

7. What opportunities for reflection do different media afford? Films on DVD can be read and reread like a book – the viewer controls, rather than being controlled – a possibility for reflection not available in broadcast. What is the proper venue for discussing this? Capitalism is the 800 lb. gorilla in the room. How do we create, if not a mass agitation, then at least a mass discussion? Tie it to the larger pressing problems of the world and how they will be better addressed by certain forms of discourse and reflection. Averting ecological catastrophe as one possible narrative – an inspiring motivator that will get people moving. How do find our way back into history? (10:09) (download)

8. What should we read next as counterpoint/antidote to Postman? The Matrix – are we headed that way? (12:33) (download)

9. How do we organize new kinds of debates about technology and society? Other issues to be addressed – class, race and gender inequality. (11:26) (download)

thinking out loud

on sunday one of my colleagues, kim white, posted a short essay on if:book, Losing America, which eloquently stated her horror at realizing how far america has slipped from its oft-stated ideals of equality and justice. as kim said “I thought America (even under the current administration) had something to do with being civilized, humane and fair. I don’t anymore.”

kim ended her piece with a parenthetical statement:

(The above has nothing and everything to do with the future of the book.)

the four of us met around a table in the institute’s new williamsburg digs yesterday and discussed why we thought kim’s statement did or didn’t belong on if:book. the result — a resounding YES.

if you’ve been reading if:book for awhile you’ve probably encountered the phrase, “we use the word book to refer to the vehicle humans use to move big ideas around society.” of course many, if not most books are about entertainment or personal improvement, but still the most important social role of books (and their close dead-tree cousins, newspapers, magazines etc.) has been to enable a conversation across space and time about the crucial issues facing society.

we realize that for the institute to make a difference we need to be asking more the right questions.although our blog covers a wide-range of technical developments relating to the evolution of communication as it goes digital, we’ve tried hard not to be simple cheerleaders for gee-whiz technology. the acid-test is not whether something is “cool” but whether and in what ways it might change the human condition.

which is why kim’s post seems so pertinent. for us it was a wake-up call reinforcing our notion that what we do exists in a social, not a technological context. what good will it be if we come up with nifty new technology for communication if the context for the communication is increasingly divorced from a caring and just social contract. Kim’s post made us realize that we have been underemphasizing the social context of our work.

as we discuss the implications of all this, we’ll try as much as possible to make these discussions “public” and to invite everyone to think it through with us.

flash memory: “the digital paper age”?

Heads are spinning in response to Samsung’s planned release of a 16 gigabyte flash drive – a string of eight 2GB flash memory cards. Flash memory is solid state data storage, as opposed to the conventional hard drive, which contains spinning mechanical parts. The implication is that the price of memory for computers will soon drop dramatically, as will the amount of energy used to power them. Moreover, you will be able to carry millions upon millions of pages on something the size of a keychain (people will probably start using smaller ones as business cards before too long). There’s definitely something reassuring about the solidity – to rely entirely on a single, rickety hard drive, or a network, to store documents is incredibly risky and unreliable. Plus, these cards are far more tolerant of shocks, bad weather and all around abuse.

Chosun Ilbo describes the remarks of Hwang Chang-gyu, Samsung’s chief executive, who said:

…the development signaled the opening of the “digital paper age.” “In the same way that civilization rapidly progressed after paper was invented 2,000 years ago, flash memory will serve as the ‘digital paper’ to store all kind of information from documents to photos and videos in the future. Mobile storage devices like CDs and hard disks will gradually disappear over the next two or three years, and flash memory will dominate the information age.”

convergence sighting: ipod phone

![]() The Motorola ROKR, a new iTunes-compatible cellphone developed for Apple, hits the stores today for Cingular subscribers. The phone will run for $249.99 and can load up to 100 songs from a computer through a USB wire. Sounds like a rip-off to me, but indicative of things to come. It also comes equipped with a camera. The cellphone is steadily swallowing up all personal media.

The Motorola ROKR, a new iTunes-compatible cellphone developed for Apple, hits the stores today for Cingular subscribers. The phone will run for $249.99 and can load up to 100 songs from a computer through a USB wire. Sounds like a rip-off to me, but indicative of things to come. It also comes equipped with a camera. The cellphone is steadily swallowing up all personal media.

Apple also unveiled its newest iPod, the “nano,” which uses solid flash memory (like in little USB memory sticks) rather than a hard drive with moving parts. It’s roughly the size of a half dozen business cards stacked together, and can hold up to 1,000 songs.

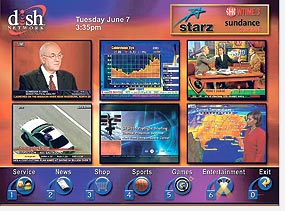

convergence sighting: the multi-channel tv screen

Several new “interactive television” services are soon to arrive that offer “mosaic” views of multiple channels, drawing TV ever nearer to full adoption of the browser, windows, and aggregator paradigms of the web (more in WSJ). It seems that once television is sufficiently like the web, it will simply be the web, or one province thereof.

microlit looms large

We’ve been hearing more and more about the phenomenon of books downloaded to a cell phone screen, so much so that even the mainstream press has been talking about a resurgence of e-books – a topic they almost entirely dropped after the efforts of Microsoft and Gemstar failed to take off a couple years back. And people are doing more than simply reading books on their phones – they can surf the web, watch soap operas and, of course, play video games as they throttle through the subway or break for lunch.

Perhaps most interesting is that while many cell phone readers are downloading conventional print texts – novels, popular nonfiction etc. – there are many more, especially in Asia, who are downloading literature that is being written exclusively for this new medium, particularly serialized novels. These stories are intended for bite-sized consumption, peppered throughout the day, week or month. And they often employ the new technology as literary device – SMS romances, mysteries spun from a single errant text message. Once again, the medium proves to be the message..

It’s hard to tell where this is going, but it’s certainly more interesting than the prefab model promoted in the first generation of e-books. There is something totally original, totally native, about this new wave of digital reading.

Take a look at this piece from yesterday’s New York Times…