The other day a fellow named Nate Stearns posted a remark on the recent post about using CommentPress in classroom situations.

This is a great idea for AP Language and Comp classes where we naturally and habitually pick apart a wide variety of essays, histories, and journalism….I could imagine whole networks of overworked high school APers tearing apart, say, Thoreau’s Walden or King’s Letter from Birmingham jail.

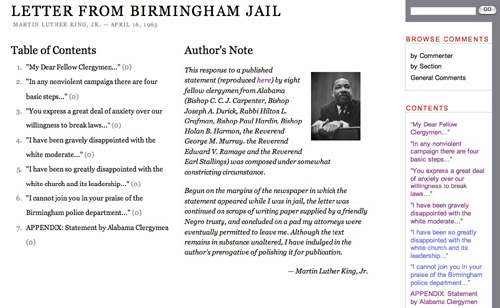

As a test, I quickly threw together an edition of MLK’s famous epistle, throwing in also as an appendix the statement by eight Alabama clergyman to which it was responding.

I’m repeating now our offer to repost, by request, this or any other available text on a unique CommentPress site dedicated to your high school or college class. It’s up to you whether we password-protect the site or leave it open. There’s a strong case to be made for insulating class discussion from public scrutiny, or worse, abuse -? especially in a high school context. In a collegiate setting, though, I can see why it might make sense to raise the stakes a bit, as Daniel Anderson suggested in another comment:

In teaching there is real leverage in having a group in place with motivation–the problem is that is extrinsic motivation in many case–grades. So, adding the public layer is really helpful in that it brings a complementary sense of creating something for others and, hopefully, internal motivation.

So there it is. We’re VERY eager to see CommentPress in action and so are offering this modest service of setting up installations. School is back in session, or will be any day now, so if you’d like us to set something up to kick off the year, drop us a note in the comments here, or email me at ben@futureofthebook.org. (Nate, just say the word and we’ll happily reproduce the MLK text for you.) Feel free to pick off the list we threw together last week, but by no means feel limited to that.

Incidentally, it was an interesting exercise breaking up King’s text into pages. The letter has no formally delineated sections but it does have about six distinct rhetorical “movements,” which I did my best to draw out here. If you request a CommentPress edition from us, feel free to be incredibly explicit as to how you’d like the text broken up and how you’d like the sections titled. For the Letter, I simply used quotations from the first sentence of paragraph of that section, which seems to do a decent job of indicating the essence of each of King’s arguments and hopefully to draw the reader in with the sound of his voice. Speaking of voice, there’s no free recording of King reading the whole Letter, but if there had been we could have easily included it as an optional audio track. If any of you have an audio version of the text you want to use, or images for that matter, point us to it/them and we might be able to work those in.