We’ve been working on our mission statement (another draft to be posted soon), and it’s given me a chance to reconsider what being part of the Institute for the Future of the Book means. Then, last week, I saw this: a Jupiter Research report claims that people are spending more time in front of the screen than with a book in their hand.

“the average online consumer spends 14 hours a week online, which is the same amount of time they watch TV.”

That is some 28 hours in front of a screen. Other analysts would say it’s higher, because this seems to only include non-work time. Of course, since we have limited time, all this screen time must be taking away from something else.

The idea that the Internet would displace other discretionary leisure activities isn’t new. Another report (pdf) from the Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society suggests that Internet usage replaces all sorts of things, including sleep time, social activities, and television watching. Most controversial was this report’s claim that internet use reduces sociability, solely on the basis that it reduces face-to-face time. Other reports suggest that sociability isn’t affected. (disclaimer – we’re affiliated with the Annenberg Center, the source of the latter report).

Regardless of time spent alone vs. the time spent face-to-face with people, the Stanford study is not taking into account the reason people are online. To quote David Weinberger:

“The real world presents all sorts of barriers that prevent us from connecting as fully as we’d like to. The Web releases us from that. If connection is our nature, and if we’re at our best when we’re fully engaged with others, then the Web is both an enabler and a reflection of our best nature.”

—Fast Company

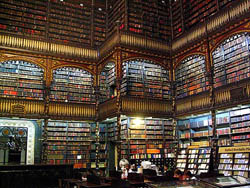

Hold onto that thought and let’s bring this back around to the Jupiter report. People use to think that it was just TV that was under attack. Magazines and newspapers, maybe, suffered too; their formats are similar to the type of content that flourishes online in blog and written-for-the-web article format. But books, it was thought, were safe because they are fundamentally different, a special object worthy of veneration.

“In addition to matching the time spent watching TV, the Internet is displacing the use of other media such as radio, magazines and books. Books are suffering the most; 37% of all online users report that they spend less time reading books because of their online activities.”

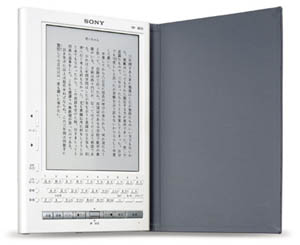

The Internet is acting as a new distribution channel for traditional media. We’ve got podcasts, streaming radio, blogs, online versions of everything. Why, then, is it a surprise that we’re spending more time online, reading more online, and enjoying fewer books? Here’s the dilemma: we’re not reading books on screens either. They just haven’t made the jump to digital.

While there has been a general decrease in book reading over the years, such a decline may come as a shocking statistic. (Yes, all statistics should be taken with a grain of salt). But I think that in some ways this is the knock of opportunity rather than the death knell for book reading.

…intensive online users are the most likely demographic to use advanced Internet technology, such as streaming radio and RSS.

So it is ‘technology’ that is keeping people from reading books online, but rather the lack of it. There is something about the current digital reading environment that isn’t suitable for continuous, lengthy monographs. But as we consider books that are born digital and take advantage of the networked environment, we will start to see a book that is shaped by its presentation format and its connections. It will be a book that is tailored for the online environment, in a way that promotes the interlinking of the digital realm, and incorporates feedback and conversation.

At that point we’ll have to deal with the transition. I found an illustrative quote, referring to reading comic books:

“You have to be able to read and look at the same time, a trick not easily mastered, especially if you’re someone who is used to reading fast. Graphic novels, or the good ones anyway, are virtually unskimmable. And until you get the hang of their particular rhythm and way of storytelling, they may require more, not less, concentration than traditional books.”

—Charles McGrath, NY Times Magazine

We’ve entered a time when the Internet’s importance is shaping the rhythms of our work and entertainment. It’s time that books were created with an awareness of the ebb and flow of this new ecology—and that’s what we’re doing at the Institute.

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian. Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year). Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

As for the device, well, the

As for the device, well, the