lately i’ve been thinking about how the institute for the future of the book should be experimental in form as well as content – an organization whose work, when appropriate, is carried out in real time in a relatively public forum. one of the key themes of our first year has been the way a network adds value to an enterprise, whether that be a thought experiment, an attempt to create a collective memory, a curated archive of best practices, or a blog that gathers and processes the world around it. i sense we are feeling our way to new methods of organizing work and distributing the results, and i want to figure out ways to make that aspect of our effort more transparent, more available to the world. this probably calls for a reevaluation of (or a re-acquaintance with) our idea of what an institute actually is, or should be.

the university-based institute arose in the age of print. scholars gathering together to make headway in a particular area of inquiry wrote papers, edited journals, held symposia and printed books of the proceedings. if books are what humans have used to move big ideas around, institutes arose to focus attention on particular big ideas and to distribute the result of that attention, mostly via print. now, as the medium shifts from printed page to networked screen, the organization and methods of “institutes” will change as well.

how they will change is what we hope to find out, and in some small way, influence. so over the next year or so we’ll be trying out a variety of different approaches to presenting our work, and new ways of facilitating debate and discussion. hopefully, we’ll draw some of you in along the way.

here’s a first try. we’ve decided (see thinking out loud) to initiate a weekly discussion at the institute where we read a book (or article or….) and then have a no-holds discussion about it — hoping to at least begin to understand some of the first order questions about what we are doing and how it fits into our perspectives on society. mostly we’re hoping to get to a place where we are regularly asking these questions in our work (whether designing software, studying the web, holding a symposium, or encouraging new publishing projects), measuring technological developments against a sense of what kind of society we’d like to live in and how a particular technology might help or hinder our getting there.

the first discussion is focused on neil postman’s “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century.” following is the audio we recorded broken into annotated chapters. we would be interested in getting people’s feedback on both form and content. (jump to the discussion)

Category Archives: publishing

marketing books on mobile phones

Harper Collins Australia’s new MobileReader service beams information about new titles and authors, and even book excerpts, to a cellphone. They’re beginning with promotions of Dean Koontz, Paul Coelho and others.

(via textually)

new york times and several philly papers cutting staff

“Times Company Announces 500 Job Cuts”

“Philly Newspapers Announce 100 Job Cuts”

From an internal email sent by Bill Keller (NY Times Executive Editor) breaking the bad news (leaked to Gawker):

I won’t pretend that it will be painless. Between the buyouts earlier this summer and the demands placed on us by the IHT and the Website — not to mention the heroic commitment we’ve made to covering the aftermath of Katrina – we don’t have a lot of slack. Like the rest of you, I found the recent spate of retirement parties more saddening than celebratory, both for the obvious personal reasons and because they represented a sapping of our collective wisdom and experience. Throughout these lean years you have worked your hearts out to perform our daily miracle, and I wish I could tell you relief was in sight.

Bob Cauthorn comments on Rebuilding Media about newspapers on the precipice:

The pro-industry spin will talk about combining web-site and print readers, which is disingenuous in exactly 1,465 ways. For example, does someone from Islamabad dipping in for one story on your web site have equal value as a seven-day-a- week local print subscriber?…

…The notion of platform shift — people moving from print to web just, you know, because — is a comfort to the media establishment as it suggests people still really, really, really love their product, they’re just selecting a different distribution mechanism.

Nonsense. The platform shift doctrine is a dangerous — and for some media companies, ultimately fatal — illusion that blinds the industry to necessary changes in the core product. Platform shift is the argument for the status quo: We don’t have to do anything different.

Speaking of not doing anything different, the Wall Street Journal ran this story about magazines experimenting with “digital editions”: “electronic versions of their publications that replicate every page of the print edition down to the table of contents and the ads.”

Cauthorn goes on about possibly breathing new life into print:

If newspapers fix their print products circulation will grow — change format, revive local coverage, alter the hierarchical approach to the news, open the ears of the newsrooms and get reporters back on the street where they belong. If you want to get really daring, re-imagine print newspapers as a three-day a week product rather than as a seven-day a week product.

As a practical matter, print newspapers only make money three days a week anyway. Imagine the interplay between a seven day a week digital product and a densely focused (and wildly profitable) three-day a week print product. Each doing different things. Each serving readers and advertisers in different ways.

The Guardian has just totally revamped its print identity, abandoning the broadsheet for the more petite Berliner format and adopting a slicker style. It’ll be worth watching whether this catches on. New packaging might make newspapers cuter, but not necessarily better.

ron silliman: “the chinese notebook”

5. Language is, first of all, a political question.

Like the problem of hunger in the world, the problem with publishing in the United States isn’t one of supply but one of distribution.

Like the problem of hunger in the world, the problem with publishing in the United States isn’t one of supply but one of distribution.

What’s worried me lately: that I go to airport bookshops and always see the same books. Because I live in New York, I can go to any number of specialized bookshops & find just about anything I want. The same is not true in many other parts of the country; the same is certainly not true in many other parts of the world. What worries me about airport bookshops is how few books they carry: how narrow a range of ideas is presented. May God help you if you’d like to buy anything other than Dan Brown in the Minneapolis/St. Paul airport. This is an exaggeration, but not by much. James Patterson is also available, as are the collected works of J. K. Rowling, and, for a limited time, those of J. R. R. Tolkien.

Into this emptiness is paraded the miracle of electronic publishing. As pushed by Jason Epstein, amongst others, the idea of print-on-demand will solve the question of supply forever more – you could go to a bookstore, request a book, and Barnes & Noble would print it out for you. (Let’s not think about copyright for the moment.) Jason Epstein believes these machines will be small enough to fit into an airport bookstore. This hasn’t happened yet, and I’m doubtful that it will any time soon, if at all. Booksellers have the supply & distribution issue down cold for Brown & Patterson & J. K. Rowling – they have no incentive to invest in these machines. When was the last time you, member of the reading public, went to complain to Barnes & Noble about their selection?

Until this marvelous future creates itself out of publishers’ good will towards humanity, people are presenting texts online, with varying degrees of success. If you have a laptop in the MSP airport (& a credit card to pay for wireless internet there), or, for that matter, any computer connected to the internet, you can go to ubu.com and browse their archive of documents of the avant-garde. Among the treasures are /ubu editions, an imprint that electronically reprints various texts as PDFs. They’re free. I have a copy of Ron Silliman’s The Chinese Notebook, a reprint of a 26-page poem which originally appeared in The Age of Huts. Ubu reprinted it (and the other two parts of The Age of Huts) with Silliman’s permission.

6. I wrote this sentence with a ballpoint pen. If I had used another, would it be a different sentence?

/Ubu editions (edited by Brian Kim Stefans) aren’t really electronic books, and don’t conceive of themselves as such. Rather, they are a way of electronically distributing a book. This PDF is 8.5” x 11”. While you can read it from a screen – I did – it’s meant to be printed out at home & read on paper. That said, this isn’t a quick and dirty presentation. Somebody (a mysterious “Goldsmith”) has gone to the trouble of making it an attractive object. It has a title page with attractive, interesting, and appropriate art (an interactive study by Mel Bochner from Aspen issue 5–6; ubu.com graciously hosts this online as well). There’s a copyright page that explains the previous. There’s even a half title page – somebody clearly knows something about book design. (How useful a half title page is in a book that’s meant to be printed out I’m not sure. It’s a pretty half title page, but it’s using another piece of your paper to print itself.) There’s also a final page, rounding off the total to 30 pages; if you print this off double-sided, you’ll have your very own beautiful stack of paper.

(Which is better than nothing.)

8. This is not speech. I wrote it.

Silliman’s text is (as these quotes might suggest) a list of 223 numbered thoughts about poetry and writing that forms a (self-contained) poem in prose. It is explicitly concerned with the form of language.

Karl Marx anticipating Walter J. Ong: “Is the Iliad possible when the printing press, and even printing machines, exist? Is it not inevitable that with the emergence of the press, the singing and the telling and the muse cease; that is, that the conditions necessary for epic poetry disappear?” (The German Ideology, p. 150; quoted in Neil Postman’s A Bridge to the 18th Century: How the Past Can Improve Our Future).

17. Everything here tends away from an aesthetic decision, which, in itself, is one.

Silliman’s text is nicely set – not beautifully, but well enough, using Baskerville. Baskerville is a neoclassical typeface, cool and rational, a product of the 18th century. Did Silliman think about this? Was the designer thinking about this? Is this how his book looked in print? in the eponymous Chinese notebook in which he wrote it? I don’t know, although my recognition of the connotations of the type inflects itself on my reading of Silliman’s poem.

21. Poem in a notebook, manuscript, magazine, book, reprinted in an anthology. Scripts and contexts differ. How could it be the same poem?

Would Silliman’s poem be the same poem if it were presented as, say, HTML? Could it be presented as HTML? This section of The Age of Huts is prose and could be without too many changes; other sections are more dependent on lines and spacing. Once a poem is in a PDF (or on a printed page), it is frozen, like a bug in amber; in HTML, type wiggles around at the viewer’s convenience. (I speak of the horrors HTML can wreak on poetry from some experience: in the evenings, I set non-English poems (in print, for the most part) for Circumference.)

47. Have we come so very far since Sterne or Pope?

Neil Postman, in his book, wonders about the same thing, answers “no”, and explains that in fact we’ve gone backwards. Disappointingly, there’s little reference to Sterne in Postman’s book, although he does point out that Oliver Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield was more widely read in the eighteenth century: possibly the literary public has never cared for the challenging.

Project Gutenberg happily presents their version of Tristram Shandy online in a plain text version: at certain points, the reader sees “(two marble plates)” or “(two lines of Greek)” and is left to wonder how much the text has changed between the page and the screen. Sterne’s novel, like Pope’s poetry, is agreeably self-aware: how Sterne would have laughed at “(page numbering skips ten pages)” in an edition without page numbers. There are a few lapses in ubu.com’s presentation of Silliman, but they’re comparably minor: some of the entries in Silliman’s list aren’t separated by a blank space, leading one to suspect the pagination was thrown out of whack in Quark. When something’s free . . .

53. Is the possibility of publishing this work automatically a part of the writing? Does it alter decisions in the work? Could I have written that if it did not?

A writer writes to communicate with a reader unknown. Publishers publish to make money. These statements are not always true – there’s no shortage of craven writers if there’s a sad dearth of virtuous publishers – but they can be taken as general rules of thumb. Where does electronic publishing fit into this set of equations? Certainly when Silliman was writing this twenty years ago he wasn’t thinking seriously about distributing his work over the Internet.

(Silliman has, for what it’s worth, an excellent blog, suggesting that had the possiblity been around twenty years ago, he would have been thinking about it.)

56. As economic conditions worsen, printing becomes prohibitive. Writers posit less emphasis on the page or book.

Why does ubu.com’s reprinting of Ron Silliman’s poetry seem more interesting to me than what Project Gutenberg is doing? Even the cheapest edition of Tristram Shandy that I can buy looks better than what they put out. (Ashamed of their text edition, one supposes, they’ve put out an HTML version of the book, which is an improvement, but not enough of one that I’d consider reading it for six hundred pages.) More to the point: it’s not that hard to find a copy of Tristram Shandy. You can even find one in one of the better airport bookstores. It’s out of copyright and any would-be publisher who wants to can print their own version of it without bothering with paying for rights.

I could not, alas, go to a bookstore and buy myself a copy of The Age of Huts because it’s been out of print for years. Thanks a lot, publishing. Good work. I could go to Amazon.com and buy a “used/collectible” copy for $113.20 – but precisely none of that money would go to Ron Silliman. But I don’t want a collectible copy: I’m interested in reading Silliman, not hoarding him. (Perhaps I start to contradict myself here.)

223. This is it.

But there are still questions. How do we ascribe value to a piece of art in a market economy? Are Plato’s ideas less valuable than those of Malcolm Gladwell because you can easily pick up the collected works of the first for less than 10% of what the two books of the second would cost you? when you can download old English translations for free on the Internet?

How valuable is a free poem on the Internet? How much more valuable is an attractive edition of a free poem on the Internet? even if you have to print it out to read it?

Why aren’t more people doing this?

introducing nexttext

The dawn of personal computing and the web has changed the way we learn, yet the tools of instruction have been sluggish to evolve. Nowhere is this more clear than with the printed textbook.

So the institute has launched nexttext, a project that seeks to accelerate the textbook’s evolution, onward from its current incarnation, the authoritative brick, toward something more fluid, more complete, and more alive – more fitting with this networked age.

Our aim is to encourage – through identifying existing experiments and facilitating new ones – the development of born-digital learning materials that will enhance, expand, and ultimately replace the printed textbook. To begin, we’ve set up a curated site showcasing the most significant digital learning experiments currently in the field. Our hunch is that by bringing these projects (and eventually, their creators) together in a single place, along with publishers and funders willing to take a risk, a concrete vision of the digital textbook for the near future might emerge. And actually happen.

So check out the site, comment, and by all means recommend other projects you think belong there. What’s up now is a seed group – things that have gotten our wheels turning so far – to be grown and expanded by the collective intelligence of the community.

thinking out loud

on sunday one of my colleagues, kim white, posted a short essay on if:book, Losing America, which eloquently stated her horror at realizing how far america has slipped from its oft-stated ideals of equality and justice. as kim said “I thought America (even under the current administration) had something to do with being civilized, humane and fair. I don’t anymore.”

kim ended her piece with a parenthetical statement:

(The above has nothing and everything to do with the future of the book.)

the four of us met around a table in the institute’s new williamsburg digs yesterday and discussed why we thought kim’s statement did or didn’t belong on if:book. the result — a resounding YES.

if you’ve been reading if:book for awhile you’ve probably encountered the phrase, “we use the word book to refer to the vehicle humans use to move big ideas around society.” of course many, if not most books are about entertainment or personal improvement, but still the most important social role of books (and their close dead-tree cousins, newspapers, magazines etc.) has been to enable a conversation across space and time about the crucial issues facing society.

we realize that for the institute to make a difference we need to be asking more the right questions.although our blog covers a wide-range of technical developments relating to the evolution of communication as it goes digital, we’ve tried hard not to be simple cheerleaders for gee-whiz technology. the acid-test is not whether something is “cool” but whether and in what ways it might change the human condition.

which is why kim’s post seems so pertinent. for us it was a wake-up call reinforcing our notion that what we do exists in a social, not a technological context. what good will it be if we come up with nifty new technology for communication if the context for the communication is increasingly divorced from a caring and just social contract. Kim’s post made us realize that we have been underemphasizing the social context of our work.

as we discuss the implications of all this, we’ll try as much as possible to make these discussions “public” and to invite everyone to think it through with us.

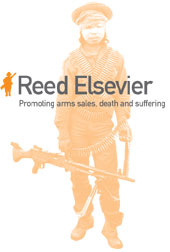

reed elsevier and the arms trade

![]() They say that sunlight is the best disinfectant. And so I’m pointing to this upsetting story about educational publishing giant Reed Elsevier’s complicity in international violence through a subsidiary (Spearhead Exhibitions) that runs one of the world’s largest arms fairs. There are the beginnings of a movement for academics and others to demand that R.E. drop this sordid business.

They say that sunlight is the best disinfectant. And so I’m pointing to this upsetting story about educational publishing giant Reed Elsevier’s complicity in international violence through a subsidiary (Spearhead Exhibitions) that runs one of the world’s largest arms fairs. There are the beginnings of a movement for academics and others to demand that R.E. drop this sordid business.

(via Crooked Timber)

digital torah

Varda Books, in collaboration with The Jewish Publication Society, has over the last few years been publishing a series of electronic editions of sacred Jewish texts, commentaries, historical studies, and critical resources, all leveraging the dynamic analytic capabilities of digital media. Popular on Varda’s online retail site, ebookshuk, are book “bundles” – collections of sacred texts and critical commentaries that enable nimble and complex intertextual analysis, or, as described for the “JPS Digital Torah Library,” serve as the “cornerstone of one’s personal, open-standards, inter-linked, cross-file-searchable, digital Jewish library.” Other bundles include “Judaic Scholar Digital Reference Library I” and “The Rabbinic Bookshelf.”

Varda Books, in collaboration with The Jewish Publication Society, has over the last few years been publishing a series of electronic editions of sacred Jewish texts, commentaries, historical studies, and critical resources, all leveraging the dynamic analytic capabilities of digital media. Popular on Varda’s online retail site, ebookshuk, are book “bundles” – collections of sacred texts and critical commentaries that enable nimble and complex intertextual analysis, or, as described for the “JPS Digital Torah Library,” serve as the “cornerstone of one’s personal, open-standards, inter-linked, cross-file-searchable, digital Jewish library.” Other bundles include “Judaic Scholar Digital Reference Library I” and “The Rabbinic Bookshelf.”

Jewish scriptural study and the Talmud have often been cited as among the earliest great hypertext traditions. Layered interpretations and non-linear modes of reading have long been central to this tradition, which continues to evolve into digital space.

lizards! defying the laws of mass market physics

Found this yesterday on changethis.com – a site devoted to publishing and disseminating manifestos. Documents are smartly designed pdfs, spread primarily through the viral channels of the blogosphere and personal email mentions.

Found this yesterday on changethis.com – a site devoted to publishing and disseminating manifestos. Documents are smartly designed pdfs, spread primarily through the viral channels of the blogosphere and personal email mentions.

In “The Long Tail” Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson predicts a new age of abundance, in which the Internet elevates niche markets and makes mass market quotas irrelevant. Of course, this is already happening, much to the distress of mass media dinosaurs, who are scrambling to protect their creaking architecture of revenue.

The “long tail” refers to the slender expanse of obscure niche sales enjoyed by a web retailer, as represented on an x-y graph. It extends from the body of high volume, mainstream sales (Wal-Mart and the like) like the caudal appendage of a lizard.

Read Manifesto: The Long Tail

Intertextual Community

When I read about Shelly Jackson’s new project–to “publish” a story by tattooing each of its 2,095 words onto the body of a different person–I thought what a great idea, and I wondered if it might actually be telling us something about the direction books are going. As the digital book begins to emerge–glorious, ephemeral, and electric–are we going to feel compelled to make something even more intimate and rarified as counterpoint?

When I read about Shelly Jackson’s new project–to “publish” a story by tattooing each of its 2,095 words onto the body of a different person–I thought what a great idea, and I wondered if it might actually be telling us something about the direction books are going. As the digital book begins to emerge–glorious, ephemeral, and electric–are we going to feel compelled to make something even more intimate and rarified as counterpoint?

“Skin Literature”