Anyone who’s ever seen a book has seen ISBNs, or International Standard Book Numbers — that string of ten digits, right above the bar code, that uniquely identifies a given title. Now come ESBNs, or Electronic Standard Book Numbers, which you’d expect would be just like ISBNs, only for electronic books. And you’d be right, but only partly.  ESBNs, which just came into existence this year, uniquely identify not only an electronic title, but each individual copy, stream, or download of that title — little tracking devices that publishers can embed in their content. And not just books, but music, video or any other discrete media form — ESBNs are media-agnostic.

ESBNs, which just came into existence this year, uniquely identify not only an electronic title, but each individual copy, stream, or download of that title — little tracking devices that publishers can embed in their content. And not just books, but music, video or any other discrete media form — ESBNs are media-agnostic.

“It’s all part of the attempt to impose the restrictions of the physical on the digital, enforcing scarcity where there is none,” David Weinberger rightly observes. On the net, it’s not so much a matter of who has the book, but who is reading the book — who is at the book. It’s not a copy, it’s more like a place. But cyberspace blurs that distinction. As Alex Pang explains, cyberspace is still a place to which we must travel. Going there has become much easier and much faster, but we are still visitors, not natives. We begin and end in the physical world, at a concrete terminal.

When I snap shut my laptop, I disconnect. I am back in the world. And it is that instantaneous moment of travel, that light-speed jump, that has unleashed the reams and decibels of anguished debate over intellectual property in the digital era. A sort of conceptual jetlag. Culture shock. The travel metaphors begin to falter, but the point is that we are talking about things confused during travel from one world to another. Discombobulation.

This jetlag creates a schism in how we treat and consume media. When we’re connected to the net, we’re not concerned with copies we may or may not own. What matters is access to the material. The copy is immaterial. It’s here, there, and everywhere, as the poet said. But when you’re offline, physical possession of copies, digital or otherwise, becomes important again. If you don’t have it in your hand, or a local copy on your desktop then you cannot experience it. It’s as simple as that. ESBNs are a byproduct of this jetlag. They seek to carry the guarantees of the physical world like luggage into the virtual world of cyberspace.

But when that distinction is erased, when connection to the network becomes ubiquitous and constant (as is generally predicted), a pervasive layer over all private and public space, keeping pace with all our movements, then the idea of digital “copies” will be effectively dead. As will the idea of cyberspace. The virtual world and the actual world will be one.

For publishers and IP lawyers, this will simplify matters greatly. Take, for example, webmail. For the past few years, I have relied exclusively on webmail with no local client on my machine. This means that when I’m offline, I have no mail (unless I go to the trouble of making copies of individual messages or printouts). As a consequence, I’ve stopped thinking of my correspondence in terms of copies. I think of it in terms of being there, of being “on my email” — or not. Soon that will be the way I think of most, if not all, digital media — in terms of access and services, not copies.

But in terms of perception, the end of cyberspace is not so simple. When the last actual-to-virtual transport service officially shuts down — when the line between worlds is completely erased — we will still be left, as human beings, with a desire to travel to places beyond our immediate perception. As Sol Gaitan describes it in a brilliant comment to yesterday’s “end of cyberspace” post:

In the West, the desire to blur the line, the need to access the “other side,” took artists to try opium, absinth, kef, and peyote. The symbolists crossed the line and brought back dada, surrealism, and other manifestations of worlds that until then had been held at bay but that were all there. The virtual is part of the actual, “we, or objects acting on our behalf are online all the time.” Never though of that in such terms, but it’s true, and very exciting. It potentially enriches my reality. As with a book, contents become alive through the reader/user, otherwise the book is a dead, or dormant, object. So, my e-mail, the blogs I read, the Web, are online all the time, but it’s through me that they become concrete, a perceived reality. Yes, we read differently because texts grow, move, and evolve, while we are away and “the object” is closed. But, we still need to read them. Esse rerum est percipi.

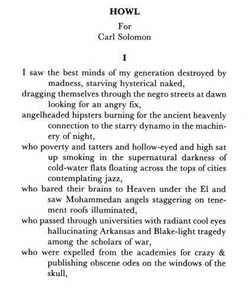

Just the other night I saw a fantastic performance of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl that took the poem — which I’d always found alluring but ultimately remote on the page — and, through the conjury of five actors, made it concrete, a perceived reality. I dug Ginsburg’s words. I downloaded them, as if across time. I was in cyberspace, but with sweat and pheremones. The Beats, too, sought sublimity — transport to a virtual world. So, too, did the cyberpunks in the net’s early days. So, too, did early Christian monastics, an analogy that Pang draws:

Just the other night I saw a fantastic performance of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl that took the poem — which I’d always found alluring but ultimately remote on the page — and, through the conjury of five actors, made it concrete, a perceived reality. I dug Ginsburg’s words. I downloaded them, as if across time. I was in cyberspace, but with sweat and pheremones. The Beats, too, sought sublimity — transport to a virtual world. So, too, did the cyberpunks in the net’s early days. So, too, did early Christian monastics, an analogy that Pang draws:

…cyberspace expresses a desire to transcend the world; Web 2.0 is about engaging with it. The early inhabitants of cyberspace were like the early Church monastics, who sought to serve God by going into the desert and escaping the temptations and distractions of the world and the flesh. The vision of Web 2.0, in contrast, is more Franciscan: one of engagement with and improvement of the world, not escape from it.

The end of cyberspace may mean the fusion of real and virtual worlds, another layer of a massively mediated existence. And this raises many questions about what is real and how, or if, that matters. But the end of cyberspace, despite all the sweeping gospel of Web 2.0, continuous computing, urban computing etc., also signals the beginning of something terribly mundane. Networks of fiber and digits are still human networks, prone to corruption and virtue alike. A virtual environment is still a natural environment. The extraordinary, in time, becomes ordinary. And undoubtedly we will still search for lines to cross.