I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of reader collaboration, prior to GAM3R TH3ORY‘s publication but to a good deal in response to its impending arrival. This notion clearly means that after the author has done one thing, the “book” becomes the accumulation of author’s and readers’ contributions.

So I’ve been thinking about collaboration. My starting point was something mentioned on my visit to the Institute — that the book’s source needs to be distributed, and it can be altered by the reader. (This is a very big idea, btw, and it’s radically altered my notion of what an e-book format’s obligations are. But that’s another discussion.)

SInce Sophie is an authoring tool, I thought, Why don’t I author something and really see what it can do? So I’ve been working with my own notion of what a book would be like that isn’t wholly limited by its medium being print. And I thought maybe I should let Sophie’s developers in on my ambition so that there’s a possibility that the features I’m envisioning might be included in the program, at least at some point in the future.

I think it’s easiest to understand my notion of collaborating with the reader by describing my work-in-progress.

So the basic notion is fairly simple, realizable already in Flash, say, or SVG:

Imagine a story, with multiple tracks. (I’m actually envisioning a short book, so let’s say 16 or 24 pages and 5 tracks.) On any page, you can go to the next or previous page. Or you can change tracks and see the next or previous page from some other track. It seems just like a 24-page book, except that the 5 tracks provide variations on what is on each page.

That’s not too exotic. And I don’t stray too far from this notion.

The first thing I’d like to do is provide multiple series of illustrations for each track. So track A might display what i call the French illustrations, or the English, or the Klee, and so on. Thus the first capability I would want to see in my authoring/reading tool is a way to change which illustration (or series of illustrations) displays within each track. You still go backwards and forwards, but maybe I like Van Gogh’s illustrations and you like Ansel Adams’. Perhaps I should mention at this point that it’s a children’s book, so I’m not casually speaking about illustrations. They are the central aspect.

The next thing I’d like to do is to allow the reader to supply illustrations, for any page (in any track), and supplant the author’s (or publisher’s) illustrations. So that perhaps my book comes with 4 series of illustrations for each track, but a reader could add many others. If these series were shared (upload your own, download others’), then perhaps you have 9 series for track A and I have 23. There has to be an easy way for the plugging in pieces, which is more on the level I’m expecting a reader to manage, as opposed to the full set of tools the author will access.

With this, the collaboration with the reader becomes two-fold — first the creation can be shared: make your own illustrations. Then, second, each individual instance becomes distinctive. If we trade “copies,” then we see the distinctive choices we each have made. Each instance is unique, especially as it contains series of illustrations that are not shared/distributed at all. In a way this reminds me of the trading card games that my ten-year-old and his friends play. They all purchase the same cards, each possessing hundreds of cards, and collect them into unique decks that they each admire and study (and then compete against, the duel being paramount). Moreover, each has some cards that none of the others has.

In addition to accepting individual illustrations or whole series of illustrations, the book should allow its text to be edited and alternate versions selected for display. I’m not sure whether one text track would be read-only, or if clicking some button would restore the text to its default form in some track, but I’d expect the author’s initial, unedited version should be retrievable in some way.

I’m far less concerned about the text than I am about this capability with illustrations, btw.

Since my project book is intended for children, I’ve thought a lot about the nature of collaboration with them. In this instance, I think will use little or no animation — it’s not an equal collaboration if the initiating author can do tricks to gain attention that the collaborating reader cannot manage. And that is one thing that makes this a book and not an animation or a cartoon and yet still strives to keep its electronicity high.

And my effort at collaboration is more like a teacher’s — here, you write/draw something, and we’ll replace what I’ve done. Perhaps in the end all the words and pictures are yours. My role was to get you started and to provide the framework. But every new collaborator can begin with the pristine master copy that anyone can access (or maybe they’ll start with a local, already altered variant that the teacher gives them). It hasn’t escaped my notice that in fact the collaboration might be between author and a class of students, not just one reader.

So. Likely as not, this first version of Sophie won’tt contain this addition/substitution capability, or perhaps not to the extent I describe. But I hope it can be added to the future feature set, or hooks anyway that will enable some plug-in to provide this capability. Because this type of collaboration seems to me to be essential.

* * *

It seems a natural expectation that a book constructed of multiple units might have multiple paths through it.

In the case of this children’s book, I don’t expect that going from track-A-page-1 to D3 to B4, and so on, is going to provide anything useful.

But I can clearly envision publications — a guidebook, a cookbook, a college course schedule, an anthology of poetry, a collection of photographs, the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, the Sayings of the Desert Fathers — in which a reader (or a teacher) may beneficially provide paths that an author overlooks. (Each of these examples of course is an instance of wholly independent units.)

In fact, I expect that Sophie’s envisioneers have thought of such circumstances already, but I raise it here as a collateral issue — collaboration with the reader must inevitably involve everything an author touches: the text, the development of the ideas, the sequence in which they are conveyed, how they are illustrated, the conclusions drawn. In a true collaboration, the author becomes something more like a director, operating perhaps at a remove (how active will the author be in reshaping the book after its publication?). Or maybe the director analogy is too strong; perhaps it’s more like an organizer — the Merry Pranksters, Christo, Lev Waleska — who launches his/her book like a vehicle (like Voyager) and then simply rides its momentum.

Once we make the book more collaborative, we remake what it means to author a book, and the creation of a book itself may come to be something more like a play or a movie or a dance, with multiple, recognized contributors.

I’m wondering how far Sophie goes in anticipating these ideas.

Category Archives: open_source

a chink in the armor of open source?

With the coming release of Sophie and our recent attendence at the Access 2 Knowledge conference, I find myself thinking about open source software development. The operating system Linux is often used as the shining example of the open source software movement. Slashdot reported an interesting ZDNet UK article, which quoted the head maintainer of the Linux production kernal, Andrew Morton, saying that he is concerned about the large number of long standing bugs in the 2.6 kernal. Software always has bugs being worked out, even the long standing ones that Morton describes. Therefore, the statement is not all that shocking or surprising.

What intrigued me was this following statement:

“One problem is that few developers are motivated to work on bugs, according to Morton. This is particularly a problem for bugs that affect old computers or peripherals, as kernel developers working for corporations don’t tend to care about out-of-date hardware, he said. Nowadays, many kernel developers are employed by IT companies, such as hardware manufacturers, which can cause problems as they can mainly be motivated by self-interest.

“If you’re a company that employs a kernel maintainer, you don’t have an interest in working on a five-year-old peripheral that no one is selling any more. I can understand that, but it is a problem as people are still using that hardware. The presence of that bug affects the whole kernel process, and can hold up the kernel — as there are bugs, but no one is fixing them,” said Morton.

Keeping contributors motivated is crucial to open source endeavors. Reputation is a major factor in what drives people to submit code to the Linux development team. In retrospect, the importance of adding code for new features over adding mundane code for bug fixes, as part of reputation building makes sense. The street cred for fixing old bugs does not seem to be sexy enough; eventhough, some of these bugs could have long term effects on the quality of the Linux OS.

Are there solutions? One solution posited by Morton is to dedicate the entire next release to fixing long standing bugs. Although it is not clear to me how open source developers would react to this constraint. Another solution might try to expand the talent pool by encouraging young, gifted (even student) programmers to work on the bugs. Their motivations might be different from current developers, and any kind of participation might offer enough motivation.

Open source software development is still a fairly new phenomenon and is far from being completely understood. As we see more clearly how motivation factors work and what they produce in the open source production model, it will be increasingly important to document, analyze and learn from these observations. The future sustainability for open source software will rely on learning how to best maintain the developers’ incentives to contribute code. Therefore, we must remind ourselves that the open source development movement is something that must be continuously nurtured. And while we can cite Linux as a success story, the project itself is not on autopilot, nor will it ever be.

an interview with bruno pellegrini

Last week I posted about Le mie elezioni, a film about the recent Italian elections constructed from footage shot by the general public, mostly part of Italy’s videoblogging community. Le mie elezioni will be released on the 15th of May: according to an article in Il manifesto more than 150 videobloggers have submitted more than 50 hours of materials which are being furiously edited right now. You can watch a rough cut of the trailer here.

The footage is being put together into an hour-long film by the website Nessuno.TV a portal for Italian videobloggers, which is run by Bruno Pellegrini, who also teaches the sociology of communications at the Universitá di Architettura in Rome. I sent him an email asking about the project; while Bruno happened to be in the U.S. last week, but his (and our) travel schedule didn’t allow him to stop by the Institute. Nonetheless, we conducted an interview, via email. My questions are in bold; his responses are indented.

The footage is being put together into an hour-long film by the website Nessuno.TV a portal for Italian videobloggers, which is run by Bruno Pellegrini, who also teaches the sociology of communications at the Universitá di Architettura in Rome. I sent him an email asking about the project; while Bruno happened to be in the U.S. last week, but his (and our) travel schedule didn’t allow him to stop by the Institute. Nonetheless, we conducted an interview, via email. My questions are in bold; his responses are indented.

Can you describe how the project came about?

It was born in a very natural way, as some of the vloggers who already participated at BlogTV (the first ever TV station broadcasting user-generated content) suggested covering the election together. Then the idea of the movie came up.

Is this project part of a larger Italian web response to media consolidation? How widely do people share your belief that the perception that big media has failed to cover things it should be covering?

I do not think this project is specific to Italy. Although the situation in my country is embarrassing I believe it is only a little ahead compared to what is going on abroad. Big media has failed (sometimes deliberately) to cover things all over the world for the last decades and the web has given people a chance to re-balance the power. Whereever and whenever there are major needs for a democracy, you can be sure something is going to happen . . . With regards to people, only a small part is conscious about what is going on, and the others are not helped by mass information . . . In general there is a common sense of distrust of politics, media and power.

In the U.S., the 2004 elections brought out – for the first time – a huge number of political bloggers; this seemed to be the first time that the blogosphere registered in the mainstream media, and there’s the perception that the U.S. blogosphere exploded at that point. Have these elections done the same thing in Italy? Or did people turn to the Internet earlier?

Not at all, unfortunately. The Italian blogosphere is not as mature as it is in the U.S. We still lack a common identity and, most of all, consciousness of the power of being media . . . Hopefully this will happen in the next political campaign, and I suspect it will come out not from the classic political separation (left and right) but from an increasing fight between young and old people with the latter trying to keep their undeserved priviledges . . .

How big is the videoblogging community in Italy? We periodically look in on it in the U.S., and while everyone loves Rocketboom, it doesn’t really seem to have taken off here as much as everyone expected (although maybe things like YouTube and Google Video are changing that). Did you find people getting interested in videoblogging because of the project, or was there already a vibrant community?

Vibrant is not exactly the right word, maybe promising would be more appropriate. I think it is a matter of critical mass and once reached it will grow exponentially like all the network related trends.

The question of copyright. Watching the clips, I couldn’t help but notice the music – songs by the Arctic Monkeys & Caparezza playing in the background, as well as video clips from the news and I think a couple of press photographs. In the U.S. documentary film makers increasingly have problems with clearance issues – the owners of the songs charge thousands of dollars for the rights to use even a few seconds of them. We’ve been covering this issue of fair use rather closely because it seems to figure in many of the things you can do with multimedia. I’m curious how much of a problem it is in Italy – is this something you worry about there?

So far it is not a problem at all and we can deal with the fair use regulation. I believe the majors will play harder in the future, especially with music and movies, but there are already good open access libraries and the Creative Commons movement is getting stronger in Italy too.

Many thanks to Bruno Pellegrini for being so generous with his time. If people have more questions about this project, don’t hesitate to leave them in the comments section.

wealth of networks

I was lucky enough to have a chance to be at The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom book launch at Eyebeam in NYC last week. After a short introduction by Jonah Peretti, Yochai Benkler got up and gave us his presentation. The talk was really interesting, covering the basic ideas in his book and delivered with the energy and clarity of a true believer. We are, he says, in a transitional period, during which we have the opportunity to shape our information culture and policies, and thereby the future of our society. From the introduction:

I was lucky enough to have a chance to be at The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom book launch at Eyebeam in NYC last week. After a short introduction by Jonah Peretti, Yochai Benkler got up and gave us his presentation. The talk was really interesting, covering the basic ideas in his book and delivered with the energy and clarity of a true believer. We are, he says, in a transitional period, during which we have the opportunity to shape our information culture and policies, and thereby the future of our society. From the introduction:

This book is offered, then, as a challenge to contemporary legal democracies. We are in the midst of a technological, economic and organizational transformation that allows us to renegotiate the terms of freedom, justice, and productivity in the information society. How we shall live in this new environment will in some significant measure depend on policy choices that we make over the next decade or so. To be able to understand these choices, to be able to make them well, we must recognize that they are part of what is fundamentally a social and political choice—a choice about how to be free, equal, productive human beings under a new set of technological and economic conditions.

During the talk Benkler claimed an optimism for the future, with full faith in the strength of individuals and loose networks to increasingly contribute to our culture and, in certain areas, replace the moneyed interests that exist now. This is the long-held promise of the Internet, open-source technology, and the infomation commons. But what I’m looking forward to, treated at length in his book, is the analysis of the struggle between the contemporary economic and political structure and the unstructured groups enabled by technology. In one corner there is the system of markets in which individuals, government, mass media, and corporations currently try to control various parts of our cultural galaxy. In the other corner there are individuals, non-profits, and social networks sharing with each other through non-market transactions, motivated by uniquely human emotions (community, self-gratification, etc.) rather than profit. Benkler’s claim is that current and future technologies enable richer non-market, public good oriented development of intellectual and cultural products. He also claims that this does not preclude the development of marketable products from these public ideas. In fact, he sees an economic incentive for corporations to support and contribute to the open-source/non-profit sphere. He points to IBM’s Global Services division: the largest part of IBM’s income is based off of consulting fees collected from services related to open-source software implementations. [I have not verified whether this is an accurate portrayal of IBM’s Global Services, but this article suggests that it is. Anecdotally, as a former IBM co-op, I can say that Benkler’s idea has been widely adopted within the organization.]

Further discussion of book will have to wait until I’ve read more of it. As an interesting addition, Benkler put up a wiki to accompany his book. Kathleen Fitzpatrick has just posted about this. She brings up a valid criticism of the wiki: why isn’t the text of the book included on the page? Yes, you can download the pdf, but the texts are in essentially the same environment—yet they are not together. This is one of the things we were trying to overcome with the Gamer Theory design. This separation highlights a larger issue, and one that we are preoccupied with at the institute: how can we shape technology to allow us handle text collaboratively and socially, yet still maintain an author’s unique voice?

italian videobloggers create open source film

An article in today’s La Repubblica reports that Italian videobloggers are at work creating an “open source film” about the recent election there. A website called Nessuno.TV is putting together a project called Le mie elezioni (“My Elections”). Visitors to the site were invited to submit their own short films. Director Stefano Mordini plans to weld them together into an hour-long documentary in mid-May.

An article in today’s La Repubblica reports that Italian videobloggers are at work creating an “open source film” about the recent election there. A website called Nessuno.TV is putting together a project called Le mie elezioni (“My Elections”). Visitors to the site were invited to submit their own short films. Director Stefano Mordini plans to weld them together into an hour-long documentary in mid-May.

The raw materials are already on display: they’ve acquired an enormous number of short films which provide an interesting cross section of Italian society. Among many others, Davide Preti interviews a husband and wife about their opposing views on the election. Stiletto Paradossale‘s series “That Thing Called Democracy” interviews people on the street in the small towns of Serrapetrona and Caldarola about what’s important about democracy. In a neat twist, Donne liberta di stampa interview a reporter from the BBC about what she thinks about the elections. And Robin Good asks the children what they think.

The raw materials are already on display: they’ve acquired an enormous number of short films which provide an interesting cross section of Italian society. Among many others, Davide Preti interviews a husband and wife about their opposing views on the election. Stiletto Paradossale‘s series “That Thing Called Democracy” interviews people on the street in the small towns of Serrapetrona and Caldarola about what’s important about democracy. In a neat twist, Donne liberta di stampa interview a reporter from the BBC about what she thinks about the elections. And Robin Good asks the children what they think.

Not all the films are interviews. Maurizio Dovigi presents a self-filmed open letter to Berlusconi. ComuniCalo eschews video in “Una notta terribile!”, a slideshow of images from the long night in Rome spent waiting for results. And Luna di Velluto offers a sped-up self-portrait of her reaction to the news on that same nights.

It’s immediately apparent that most of these films are for the left. This isn’t an isolated occurance: the Italian left seems to have understood that the network can be a political force. In January, I noted the popularity of comic Beppe Grillo’s blog. Since then, it’s only become more popular: recent entries have averaged around 3000 comments each (this one, from four days ago, has 4123). Nor is he limiting himself to the blog: there are weekly PDF summaries of issues, MeetUp groups, and a blook/DVD combo. Compare this hyperactivity to the staid websites of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party and the Silvio Berlusconi Fans Club.

It’s immediately apparent that most of these films are for the left. This isn’t an isolated occurance: the Italian left seems to have understood that the network can be a political force. In January, I noted the popularity of comic Beppe Grillo’s blog. Since then, it’s only become more popular: recent entries have averaged around 3000 comments each (this one, from four days ago, has 4123). Nor is he limiting himself to the blog: there are weekly PDF summaries of issues, MeetUp groups, and a blook/DVD combo. Compare this hyperactivity to the staid websites of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party and the Silvio Berlusconi Fans Club.

The Italian left’s embrace of the Internet has partially been out of necessity: as Berlusconi owns most of the Italian media, views that counter his have been largely absent. There’s the perception that the mainstream media has stagnated, though there’s clearly a thirst for intelligent commentary: an astounding five million viewers tuned in to an appearance by Umberto Eco on TV two months ago. Bruno Pellegrini, who runs Nessuno.TV, suggests that the Internet can offer a corrective alternative:

We want to be a TV ‘made by those who watch it. A participatory TV, in which the spectators actively contribute to the construction of a palimpsest. We are riding the tendencies of the moment, using the technologies available with the lowest costs, and involving those young people who are convinced that an alternative to regular TV can be constructed, and we’re starting that.

They’re off to an impressive start, and I’ll be curious to see how far they get with this. One nagging thought: most of these videos would have copyright issues in the U.S. Many use background music that almost certainly hasn’t been cleared by the owners. Some use video clips and photos that are probably owned by the mainstream press. The dread hand of copyright enforcement isn’t as strong in Italy as it is in the U.S., but it still exists. It would be a shame if rights issues brought down such a worthy community project.

open source DRM?

A couple of weeks ago, Sun Microsystems released specifications and source code for DReaM, an open-source, “royalty-free digital rights management standard” designed to operate on any certified device, licensing rights to the user rather than to any particular piece of hardware. DReaM (Digital Rights Management — everywhere availble) is the centerpiece of Sun’s Open Media Commons initiative, announced late last summer as an alternative to Microsoft, Apple and other content protection systems. Yesterday, it was the subject of Eliot Van Buskirk’s column in Wired:

Sun is talking about a sea change on the scale of the switch from the barter system to paper money. Like money, this standardized DRM system would have to be acknowledged universally, and its rules would have to be easily converted to other systems (the way U.S. dollars are officially used only in America but can be easily converted into other currency). Consumers would no longer have to negotiate separate deals with each provider in order to access the same catalog (more or less). Instead, you — the person, not your device — would have the right to listen to songs, and those rights would follow you around, as long as you’re using an approved device.

The OMC promises to “promote both intellectual property protection and user privacy,” and certainly DReaM, with its focus on interoperability, does seem less draconian than today’s prevailing systems. Even Larry Lessig has endorsed it, pointing with satisfaction to a “fair use” mechanism that is built into the architecture, ensuring that certain uses like quotation, parody, or copying for the classroom are not circumvented. Van Buskirk points out, however, that the fair use protection is optional and left to the discretion of the publisher (not a promising sign). Interestingly, the debate over DReaM has caused a rift among copyright progressives. Van Buskirk points to an August statement from the Electronic Frontier Foundation criticizing DReaM for not going far enough to safeguard fair use, and for falsely donning the mantle of openness:

Using “commons” in the name is unfortunate, because it suggests an online community committed to sharing creative works. DRM systems are about restricting access and use of creative works.

True. As terms like “commons” and “open source” seep into the popular discourse, we should be increasingly on guard against their co-option. Yet I applaud Sun for trying to tackle the interoperability problem, shifting control from the manufacturers to an independent standards body. But shouldn’t mandatory fair use provisions be a baseline standard for any progressive rights scheme? DReaM certainly looks like less of a nightmare than plain old DRM but does it go far enough?

on the importance of the collective in electronic publishing

(The following polemic is cross-posted from the planning site for a small private meeting the Institute is holding later this month to discuss the possible establishment of an electronic press. Also posted on The Valve.)

One of the concerns that often gets raised early in discussions of electronic scholarly publishing is that of business model — how will the venture be financed, and how will its products be, to use a word I hate, monetized? What follows should not at all suggest that I don’t find such questions important. Clearly, they’re crucial; unless an electronic press is in some measure self-sustaining, it simply won’t last long. Foundations might be happy to see such a venture get started, but nobody wants to bankroll it indefinitely.

I also don’t want to fall prey to what has been called the “paper = costly, electronic = free” fallacy. Obviously, many of the elements of traditional academic press publishing that cost — whether in terms of time, or of money, or both — will still exist in an all-electronic press. Texts still must be edited and transformed from manuscript to published format, for starters. Plus, there are other costs associated with the electronic — computers and their programming, to take only the most obvious examples — that don’t exist in quite the same measure in print ventures.

But what I do want to argue for, building off of John Holbo’s recent post, is the importance of collective, cooperative contributions of academic labor to any electronic scholarly publishing venture. For a new system like that we’re hoping to build in ElectraPress to succeed, we need a certain amount of buy-in from those who stand to benefit from the system, a commitment to get the work done, and to make the form succeed.

I’ve been thinking about this need for collectivity through a comparison with the model of open-source software. Open source has succeeded, in large part, due to the commitments that hundreds of programmers have made, not just to their individual projects but to the system as a whole. Most of these programmers work regular, paid gigs, working on corporate projects, all the while reserving some measure of their time and devotion for non-profit, collective projects. That time and devotion are given freely because of a sense of the common benefits that all will reap from the project’s success.

So with academics. We are paid, by and large, and whether we like it or not, for delivering certain kinds of knowledge-work to paying clients. We teach, we advise, we lecture, and so forth, and all of this is primarily done within the constraints of someone else’s needs and desires. But the job also involves, or allows, to varying degrees, reserving some measure of our time and devotion for projects that are just ours, projects whose greatest benefits are to our own pleasure and to the collective advancement of the field as a whole.

If we’re already operating to that extent within an open-source model, what’s to stop us from taking a further plunge, opening publishing cooperatives, and thereby transforming academic publishing from its current (if often inadvertent) non-profit status to an even lower-cost, collectively underwritten financial model?

I can imagine two possible points of resistance within traditional humanities scholars toward such a plan, points that originate in individualism and technophobia.

Individualism, first: it’s been pointed out many times that scholars in the humanities have strikingly low rates of collaborative authorship. Politically speaking, this is strange. Even as many of us espouse communitarian (or even Marxist) ideological positions, and even as we work to break down long-held bits of thinking like the “great man” theory of history, or of literary production, we nonetheless cling to the notion that our ideas are our own, that scholarly work is the product of a singular brain. Of course, when we stop to think about it, we’re willing to admit that it’s not true — that, of course, is what the acknowledgments and footnotes of our books are for — but venturing into actual collaborations remains scary. Moreover, many of us seem to have the same kinds of nervousness about group projects that our students have: What if others don’t pull their weight? Will we get stuck with all of the work, but have to share the credit?

I want to answer that latter concern by suggesting, as John has, that a collective publishing system might operate less like those kinds of group assignments than like food co-ops: in order to be a member of the co-op — and membership should be required in order to publish through it — everyone needs to put in a certain number of hours stocking the shelves and working the cash register. As to the first mode of this individualist anxiety, though, I’m not sure what to say, except that no scholar is an island, that we’re all always working collectively, even when we think we’re most alone. Hand off your manuscript to a traditional press, and somebody’s got to edit it, and typeset it, and print it; why shouldn’t that somebody be you?

Here’s where the technophobia comes in, or perhaps it’s just a desire to have someone else do the production work masquerading as a kind of technophobia, because many of the responses to that last question seem to revolve around either not knowing how to do this kind of publishing work or not wanting to take on the burden of figuring it out. But I strongly suspect that there will come a day in the not too distant future when we look back on those of us who have handed our manuscripts over to presses for editing, typesetting, printing, and dissemination in much the same way that I currently look back on those emeriti who had their secretaries — or better still, their wives — type their manuscripts for them. For better or for worse, word processing has become part of the job; with the advent of the web and various easily learned authoring tools, editing and publishing are becoming part of the job as well.

I’m strongly of the opinion that, if academic publishing is going to survive into the next decades, we need to stop thinking about how it’s going to be saved, and instead start thinking about how we are going to save it. And a business model that relies heavily on the collective — particularly, on labor that is shared for everyone’s benefit — seems to me absolutely crucial to such a plan.

another round: britannica versus wikipedia

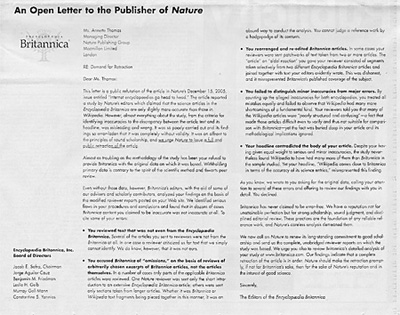

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

Several interesting things are going on here. Because Britannica chose to place an ad in the Times, it shifted the argument and debate away from the peer review / editorial context into one of rhetoric and public relations. Further, their conscious move to take the argument to the “public” or the “masses” with an open letter is ironic because the New York TImes does not display its print ads online, therefore access of the letter is limited to the Time’s print readership. (Not to mention, the letter is addressed to the Nature Publishing Group located in London. If anyone knows that a similar letter was printed in the UK, please let us know.) Readers here can click on the thumbnail image to read the entire text of the letter. Ben raised an interesting question here today, asking where one might post a similar open letter on the Internet.

Britannica cites many important criticisms of Nature’s article, including: using text not from Britannica, using excerpts out of context, giving equal weight to minor and major errors, and writing a misleading headline. If their accusations are true, then Nature should redo the study. However, to harp upon Nature’s methods is to miss the point. Britannica cannot do anything to stop Wikipedia, except to try to discredit to this study. Disproving Nature’s methodology will have a limited effect on the growth of Wikipedia. People do not mind that Wikipedia is not perfect. The JKF assassination / Seigenthaler episode showed that. Britannica’s efforts will only lead to more studies, which will inevitably will show errors in both encyclopedias. They acknowledge in today’s letter that, “Britannica has never claimed to be error-free.” Therefore, they are undermining their own authority, as people who never thought about the accuracy of Britannica are doing just that now. Perhaps, people will not mind that Britannica contains errors as well. In their determination to show the world that of the two encyclopedias which both content flaws, they are also advertising that of the two, the free one has some-what more errors.

In the end, I agree with Ben’s previous post that the Nature article in question has a marginal relevance to the bigger picture. The main point is that Wikipedia works amazingly well and contains articles that Britannica never will. It is a revolutionary way to collaboratively share knowledge. That we should give consideration to the source of our information we encounter, be it the Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia, Nature or the New York Time, is nothing new.

britannica bites back (do we care?)

![]() Late last year, Nature Magazine let loose a small shockwave when it published results from a study that had compared science articles in Encyclopedia Britannica to corresponding entries in Wikipedia. Both encyclopedias, the study concluded, contain numerous errors, with Britannica holding only a slight edge in accuracy. Shaking, as it did, a great many assumptions of authority, this was generally viewed as a great victory for the five-year-old Wikipedia, vindicating its model of decentralized amateur production.

Late last year, Nature Magazine let loose a small shockwave when it published results from a study that had compared science articles in Encyclopedia Britannica to corresponding entries in Wikipedia. Both encyclopedias, the study concluded, contain numerous errors, with Britannica holding only a slight edge in accuracy. Shaking, as it did, a great many assumptions of authority, this was generally viewed as a great victory for the five-year-old Wikipedia, vindicating its model of decentralized amateur production.

Now comes this: a document (download PDF) just published on the Encyclopedia Britannica website claims that the Nature study was “fatally flawed”:

Almost everything about the journal’s investigation, from the criteria for identifying inaccuracies to the discrepancy between the article text and its headline, was wrong and misleading.

What are we to make of this? And if Britannica’s right, what are we to make of Nature? I can’t help but feel that in the end it doesn’t matter. Jabs and parries will inevitably be exchanged, yet Wikipedia continues to grow and evolve, containing multitudes, full of truth and full of error, ultimately indifferent to the censure or approval of the old guard. It is a fact: Wikipedia now contains over a million articles in english, nearly 223 thousand in Polish, nearly 195 thousand in Japanese and 104 thousand in Spanish; it is broadly consulted, it is free and, at least for now, non-commercial.

At the moment, I feel optimistic that in the long arc of time Wikipedia will bend toward excellence. Others fear that muddled mediocrity can be the only result. Again, I find myself not really caring. Wikipedia is one of those things that makes me hopeful about the future of the web. No matter how accurate or inaccurate it becomes, it is honest. Its messiness is the messiness of life.

sharing goes mainstream

Ben’s post on the Google book project mentioned a fundamental tenet of the Institute: the network is the environment for the future of reading and writing, and that’s why we care about network-related issues. While the goal of the network isn’t reducable to a single purpose, if you could say it was any one thing it would be: sharing. It’s why Tim Berners-Lee created it in the first place—to share scientific research. It’s why people put their lives on blogs, their photos on flickr, their movies on YouTube. And it is why the people who want to sell things are so anxious about putting their goods online. The bottom line is this: the ‘net is about sharing, that’s what it’s for.

Ben’s post on the Google book project mentioned a fundamental tenet of the Institute: the network is the environment for the future of reading and writing, and that’s why we care about network-related issues. While the goal of the network isn’t reducable to a single purpose, if you could say it was any one thing it would be: sharing. It’s why Tim Berners-Lee created it in the first place—to share scientific research. It’s why people put their lives on blogs, their photos on flickr, their movies on YouTube. And it is why the people who want to sell things are so anxious about putting their goods online. The bottom line is this: the ‘net is about sharing, that’s what it’s for.

Time magazine had an article in the March 20th issue on open-source and innovation-at-the-edges (by Lev Grossman). Those aren’t new ideas around office, but when I saw the phrase the “authorship of innovation is shifting from the Few to the Many” I realized that, for the larger public, they are still slightly foreign, that the distant intellectual altruism of the Enlightenment is being recast as the open-source movement, and that the notion of an intellectual commons is being rejuvenated in the public consciousness. True, Grossman puts out the idea of shared innovation as a curiosity—it’s a testament to the momentum of our contemporary notions of copyright that the cultural environment is antagonistic to giving away ideas—but I applaud any injection of the open-source ideal into the mainstream. Especially ideas like this:

Admittedly, it’s counterintuitive: until now the value of a piece of intellectual property has been defined by how few people possess it. In the future the value will be defined by how many people possess it.

I hope the article will seed the public mind with intimations of a world where the benefits of intellectual openness and sharing are assumed, rather than challenged.

Raising the public consciousness around issues of openness and sharing is one of the goals of the Institute. We’re happy to have help from a magazine with Time’s circulation, but most of all, I’m happy that the article is turning public attention in the direction of an open network, shared content, and a rich digital commons.