Two products that will most likely never be owned by the same teenager: The hundred dollar Laptop from MIT and the hundred dollar “pentop” computerized pen called the Fly. While the hundred dollar laptop (as we’ve said a few times on this site already) is promoted as a device to bring children of underdeveloped countries into the silicon era, the Fly is a device that will help technology-saturated 8 to 14 year olds keep track of soccer practice, learn to read, and solve arithmetic equations. Equipped with a microphone and OCR software, the Fly will read aloud what you write: if you use the special paper that comes with the product, you can draw a calculator and the calculator becomes functional. It’s all very Harold and the Purple Crayon .

Two products that will most likely never be owned by the same teenager: The hundred dollar Laptop from MIT and the hundred dollar “pentop” computerized pen called the Fly. While the hundred dollar laptop (as we’ve said a few times on this site already) is promoted as a device to bring children of underdeveloped countries into the silicon era, the Fly is a device that will help technology-saturated 8 to 14 year olds keep track of soccer practice, learn to read, and solve arithmetic equations. Equipped with a microphone and OCR software, the Fly will read aloud what you write: if you use the special paper that comes with the product, you can draw a calculator and the calculator becomes functional. It’s all very Harold and the Purple Crayon .

In his review of the Fly’s capabilities in todays New York Times, David Pogue is largely enthusiastic about the device, finding it both practical and appealing (if a tad buggy in its original version). Most of all, he seems to think the Fly’s too-cool-for-school additional features are necessary innovation in a market that he says has begun to dry up — digital educational products for children. According to Pogue:

When it comes to children’s technology, a sort of post-educational age has dawned. Last year, Americans bought only one-third as much educational software as they did in 2000. Once highflying children’s software companies have dwindled or disappeared. The magazine once called Children’s Software Review is now named Children’s Technology Review, and over half of its coverage now is dedicated to entertainment titles (for Game Boy, PlayStation and the like) that have no educational component.

If Pogue is right, and educational software is on its way out, does this mean that everything has moved over to the web? And what implication does this downturn have for the hundred dollar laptop project?

Category Archives: OCR

having browsed google print a bit more…

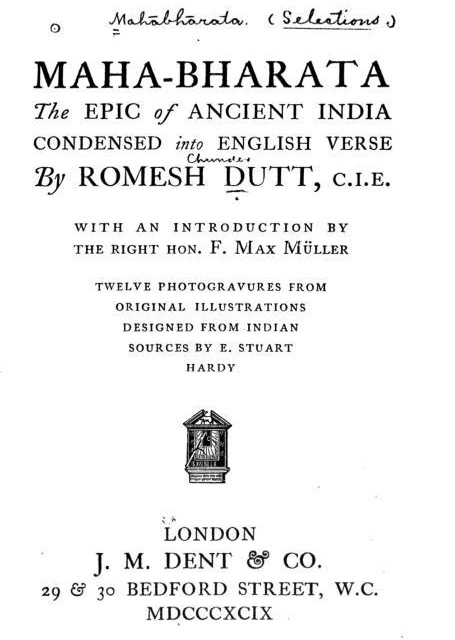

…I realize I was over-hasty in dismissing the recent additions made since book scanning resumed earlier this month. True, many of the fine wines in the cellar are there only for the tasting, but the vintage stuff can be drunk freely, and there are already some wonderful 19th century titles, at this point mostly from Harvard. The surest way to find them is to search by date, or by title and date. Specify a date range in advanced search or simply enter, for example, “date: 1890” and a wealth of fully accessible texts comes up, any of which can be linked to from a syllabus. An astonishing resource for teachers and students.

The conclusion: Google Print really is shaping up to be a library, that is, of the world pre-1923 — the current line of demarcation between copyright and the public domain. It’s a stark reminder of how over-extended copyright is. Here’s an 1899 english printing of The Mahabharata:

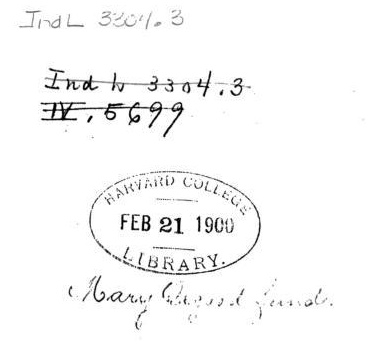

A charming detail found on the following page is this old Harvard library stamp that got scanned along with the rest:

google print’s not-so-public domain

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

The problem is, there really isn’t all that much there. Google’s gotten a lot of bad press for its supposedly cavalier attitude toward copyright, but spend a few minutes browsing Google Print and you’ll see just how publisher-centric the whole affair is. The idea of a text being in the public domain really doesn’t amount to much if you’re only talking about antique manuscripts, and these are the only books that they’ve made fully accessible. Daisy Miller‘s copyright expired long ago but, with the exception of Harvard’s illustrated 1892 copy, all the available scanned editions are owned by modern publishers and are therefore only snippeted. This is not an online library, it’s a marketing program. Google Print will undeniably have its uses, but we shouldn’t confuse it with a library.

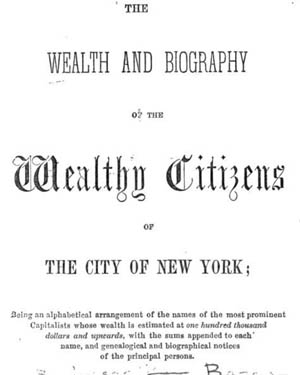

(An interesting offering from the stacks of the New York Public Library is this mid-19th century biographic registry of the wealthy burghers of New York: “Capitalists whose wealth is estimated at one hundred thousand dollars and upwards…”)