This is potentially a big deal for scholarly publishing in the sciences. Inspired by popular “preprint” servers like the Cornell-hosted arXiv.org, the journal Nature just launched a site, “Nature Precedings”, where unreviewed scientific papers can be posted under a CC license, then discussed, voted upon, and cited according to standards usually employed for peer-reviewed scholarship.

Over the past decade, preprint archives have become increasingly common as a means of taking the pulse of new scientific research before official arbitration by journals, and as a way to plant a flag in front of the gatekeepers’ gates in order to outmaneuver competition in a crowded field. Peer review journals are still the sine qua non in terms of the institutional warranting of scholarship, and in the process of academic credentialling and the general garnering of prestige, but the Web has emerged as the arena where new papers first see the light of day and where discussion among scholars begins to percolate. More and more, print publication has been transforming into a formal seal of approval at the end of a more unfiltered, networked process. Clearly, Precedings is Nature‘s effort to claim some of the Web territory for itself.

From a cursory inspection of the site, it appears that they’re serious about providing a stable open access archive, referencable in perpetuity through broadly accepted standards like DOI (Digital Object Identifier) and Handles (which, as far as I can tell, are a way of handling citations of revised papers). They also seem earnest about hosting an active intellectual community, providing features like scholar profiles and a variety of feedback mechanisms. This is a big step for Nature, especially following their tentative experiment last year with opening up peer review. At that time they seemed almost keen to prove that a re-jiggering of the review process would fail to yield interesting results and they stacked their “trial” against the open approach by not actually altering the process, or ultimately, the stakes, of the closed-door procedure. Not surprisingly, few participated and the experiment was declared an interesting failure. Obviously their thinking on this matter did not end there.

Hosting community-moderated works-in-development might just be a new model for scholarly presses, and Nature might just be leading the way. We’ll be watching this one.

More on David Weinberger’s blog.

Category Archives: nature

perelman’s proof / wsj on open peer review

Last week got off to an exciting start when the Wall Street Journal ran a story about “networked books,” the Institute’s central meme and very own coinage. It turns out we were quoted in another WSJ item later that week, this time looking at the science journal Nature, which over the summer has been experimenting with opening up its peer review process to the scientific community (unfortunately, this article, like the networked books piece, is subscriber only).

I like this article because it smartly weaves in the story of Grigory (Grisha) Perelman, which I had meant to write about earlier. Perelman is a Russian topologist who last month shocked the world by turning down the Fields medal, the highest honor in mathematics. He was awarded the prize for unraveling a famous geometry problem that had baffled mathematicians for a century.

I like this article because it smartly weaves in the story of Grigory (Grisha) Perelman, which I had meant to write about earlier. Perelman is a Russian topologist who last month shocked the world by turning down the Fields medal, the highest honor in mathematics. He was awarded the prize for unraveling a famous geometry problem that had baffled mathematicians for a century.

There’s an interesting publishing angle to this, which is that Perelman never submitted his groundbreaking papers to any mathematics journals, but posted them directly to ArXiv.org, an open “pre-print” server hosted by Cornell. This, combined with a few emails notifying key people in the field, guaranteed serious consideration for his proof, and led to its eventual warranting by the mathematics community. The WSJ:

…the experiment highlights the pressure on elite science journals to broaden their discourse. So far, they have stood on the sidelines of certain fields as a growing number of academic databases and organizations have gained popularity.

One Web site, ArXiv.org, maintained by Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., has become a repository of papers in fields such as physics, mathematics and computer science. In 2002 and 2003, the reclusive Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman circumvented the academic-publishing industry when he chose ArXiv.org to post his groundbreaking work on the Poincaré conjecture, a mathematical problem that has stubbornly remained unsolved for nearly a century. Dr. Perelman won the Fields Medal, for mathematics, last month.

(Warning: obligatory horn toot.)

“Obviously, Nature’s editors have read the writing on the wall [and] grasped that the locus of scientific discourse is shifting from the pages of journals to a broader online conversation,” wrote Ben Vershbow, a blogger and researcher at the Institute for the Future of the Book, a small, Brooklyn, N.Y., , nonprofit, in an online commentary. The institute is part of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center for Communication.

Also worth reading is this article by Sylvia Nasar and David Gruber in The New Yorker, which reveals Perelman as a true believer in the gift economy of ideas:

Perelman, by casually posting a proof on the Internet of one of the most famous problems in mathematics, was not just flouting academic convention but taking a considerable risk. If the proof was flawed, he would be publicly humiliated, and there would be no way to prevent another mathematician from fixing any errors and claiming victory. But Perelman said he was not particularly concerned. “My reasoning was: if I made an error and someone used my work to construct a correct proof I would be pleased,” he said. “I never set out to be the sole solver of the Poincaré.”

Perelman’s rejection of all conventional forms of recognition is difficult to fathom at a time when every particle of information is packaged and owned. He seems almost like a kind of mystic, a monk who abjures worldly attachment and dives headlong into numbers. But according to Nasar and Gruber, both Perelman’s flouting of academic publishing protocols and his refusal of the Fields medal were conscious protests against what he saw as the petty ego politics of his peers. He claims now to have “retired” from mathematics, though presumably he’ll continue to work on his own terms, in between long rambles through the streets of St. Petersburg.

Regardless, Perelman’s case is noteworthy as an example of the kind of critical discussions that scholars can now orchestrate outside the gate. This sort of thing is generally more in evidence in the physical and social sciences, but ought too to be of great interest to scholars in the humanities, who have only just begun to explore the possibilities. Indeed, these are among our chief inspirations for MediaCommons.

Academic presses and journals have long functioned as the gatekeepers of authoritative knowledge, determining which works see the light of day and which ones don’t. But open repositories like ArXiv have utterly changed the calculus, and Perelman’s insurrection only serves to underscore this fact. Given the abundance of material being published directly from author to public, the critical task for the editor now becomes that of determining how works already in the daylight ought to be received. Publishing isn’t an endpoint, it’s the beginning of a process. The networked press is a guide, a filter, and a discussion moderator.

Nature seems to grasp this and is trying with its experiment to reclaim some of the space that has opened up in front of its gates. Though I don’t think they go far enough to effect serious change, their efforts certainly point in the right direction.

transmitting live from cambridge: wikimania 2006

I’m at the Wikimania 2006 conference at Harvard Law School, from where I’ll be posting over the course of the three-day conference (schedule). The big news so far (as has already been reported in a number of blogs) came from this morning’s plenary address by Jimmy Wales, when he announced that Wikipedia content was going to be included in the Hundred Dollar Laptop. Exactly what “Wikipedia content” means isn’t clear to me at the moment – Wikipedia content that’s not on a network loses a great deal of its power – but I’m sure details will filter out soon.

I’m at the Wikimania 2006 conference at Harvard Law School, from where I’ll be posting over the course of the three-day conference (schedule). The big news so far (as has already been reported in a number of blogs) came from this morning’s plenary address by Jimmy Wales, when he announced that Wikipedia content was going to be included in the Hundred Dollar Laptop. Exactly what “Wikipedia content” means isn’t clear to me at the moment – Wikipedia content that’s not on a network loses a great deal of its power – but I’m sure details will filter out soon.

This move is obvious enough, perhaps, but there are interesting ramifications of this. Some of these were brought out during the audience question period during the next panel that I attended, in which Alex Halavis talked about issues of evaluating Wikipedia’s topical coverage, and Jim Giles, the writer of the Nature study comparing the Wikipedia & the Encyclopædia Britannica. The subtext of both was the problem of authority and how it’s perceived. We measure the Wikipedia against five hundred years of English-language print culture, which the Encyclopædia Britannica represents to many. What happens when the Wikipedia is set loose in a culture that has no print or literary tradition? The Wikipedia might assume immense cultural importance. The obvious point of comparison is the Bible. One of the major forces behind creating Unicode – and fonts to support the languages used in the developing world – is SIL, founded with the aim of printing the Bible in every language on Earth. It will be interesting to see if Wikipedia gets as far.

on the future of peer review in electronic scholarly publishing

Over the last several months, as I’ve met with the folks from if:book and with the quite impressive group of academics we pulled together to discuss the possibility of starting an all-electronic scholarly press, I’ve spent an awful lot of time thinking and talking about peer review — how it currently functions, why we need it, and how it might be improved. Peer review is extremely important — I want to acknowledge that right up front — but it threatens to become the axle around which all conversations about the future of publishing get wrapped, like Isadora Duncan’s scarf, strangling any possible innovations in scholarly communication before they can get launched. In order to move forward with any kind of innovative publishing process, we must solve the peer review problem, but in order to do so, we first have to separate the structure of peer review from the purposes it serves — and we need to be a bit brutally honest with ourselves about those purposes, distinguishing between those purposes we’d ideally like peer review to serve and those functions it actually winds up fulfilling.

The issue of peer review has of course been brought back to the front of my consciousness by the experiment with open peer review currently being undertaken by the journal Nature, as well as by the debate about the future of peer review that the journal is currently hosting (both introduced last week here on if:book). The experiment is fairly simple: the editors of Nature have created an online open review system that will run parallel to its traditional anonymous review process.

From 5 June 2006, authors may opt to have their submitted manuscripts posted publicly for comment.

Any scientist may then post comments, provided they identify themselves. Once the usual confidential peer review process is complete, the public ‘open peer review’ process will be closed. Editors will then read all comments on the manuscript and invite authors to respond. At the end of the process, as part of the trial, editors will assess the value of the public comments.

As several entries in the web debate that is running alongside this trial make clear, though, this is not exactly a groundbreaking model; the editors of several other scientific journals that already use open review systems to varying extents have posted brief comments about their processes. Electronic Transactions in Artificial Intelligence, for instance, has a two-stage process, a three-month open review stage, followed by a speedy up-or-down refereeing stage (with some time for revisions, if desired, inbetween). This process, the editors acknowledge, has produced some complications in the notion of “publication,” as the texts in the open review stage are already freely available online; in some sense, the journal itself has become a vehicle for re-publishing selected articles.

Peer review is, by this model, designed to serve two different purposes — first, fostering discussion and feedback amongst scholars, with the aim of strengthening the work that they produce; second, filtering that work for quality, such that only the best is selected for final “publication.” ETAI’s dual-stage process makes this bifurcation in the purpose of peer review clear, and manages to serve both functions well. Moreover, by foregrounding the open stage of peer review — by considering an article “published” during the three months of its open review, but then only “refereed” once anonymous scientists have held their up-or-down vote, a vote that comes only after the article has been read, discussed, and revised — this kind of process seems to return the center of gravity in peer review to communication amongst peers.

I wonder, then, about the relatively conservative move that Nature has made with its open peer review trial. First, the journal is at great pains to reassure authors and readers that traditional, anonymous peer review will still take place alongside open discussion. Beyond this, however, there seems to be a relative lack of communication between those two forms of review: open review will take place at the same time as anonymous review, rather than as a preliminary phase, preventing authors from putting the public comments they receive to use in revision; and while the editors will “read” all such public comments, it appears that only the anonymous reviews will be considered in determining whether any given article is published. Is this caution about open review an attempt to avoid throwing out the baby of quality control with the bathwater of anonymity? In fact, the editors of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics present evidence (based on their two-stage review process) that open review significantly increases the quality of articles a journal publishes:

Our statistics confirm that collaborative peer review facilitates and enhances quality assurance. The journal has a relatively low overall rejection rate of less than 20%, but only three years after its launch the ISI journal impact factor ranked Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics twelfth out of 169 journals in ‘Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences’ and ‘Environmental Sciences’.

These numbers support the idea that public peer review and interactive discussion deter authors from submitting low-quality manuscripts, and thus relieve editors and reviewers from spending too much time on deficient submissions.

By keeping anonymous review and open review separate, without allowing the open any precedence, Nature is allowing itself to avoid asking any risky questions about the purposes of its process, and is perhaps inadvertently maintaining the focus on peer review’s gatekeeping function. The result of such a focus is that scholars are less able to learn from the review process, less able to put comments on their work to use, and less able to respond to those comments in kind.

If anonymous, closed peer review processes aren’t facilitating scholarly discourse, what purposes do they serve? Gatekeeping, as I’ve suggested, is a primary one; as almost all of the folks I’ve talked with this spring have insisted, peer review is necessary to ensuring that the work published by scholarly outlets is of sufficiently high quality, and anonymity is necessary in order to allow reviewers the freedom to say that an article should not be published. In fact, this question of anonymity is quite fraught for most of the academics with whom I’ve spoken; they have repeatedly responded with various degrees of alarm to suggestions that their review comments might in fact be more productive delivered publicly, as part of an ongoing conversation with the author, rather than as a backchannel, one-way communication mediated by an editor. Such a position may be justifiable if, again, the primary purpose of peer review is quality control, and if the process is reliably scrupulous. However, as other discussants in the Nature web debate point out, blind peer review is not a perfect process, subject as it is to all kinds of failures and abuses, ranging from flawed articles that nonetheless make it through the system to ideas that are appropriated by unethical reviewers, with all manner of cronyism and professional jealousy inbetween.

So, again, if closed peer review processes aren’t serving scholars in their need for feedback and discussion, and if they can’t be wholly relied upon for their quality-control functions, what’s left? I’d argue that the primary purpose that anonymous peer review actually serves today, at least in the humanities (and that qualifier, and everything that follows from it, opens a whole other can of worms that needs further discussion — what are the different needs with respect to peer review in the different disciplines?), is that of institutional warranting, of conveying to college and university administrations that the work their employees are doing is appropriate and well-thought-of in its field, and thus that these employees are deserving of ongoing appointments, tenure, promotions, raises, and whathaveyou.

Are these the functions that we really want peer review to serve? Vast amounts of scholars’ time is poured into the peer review process each year; wouldn’t it be better to put that time into open discussions that not only improve the individual texts under review but are also, potentially, productive of new work? Isn’t it possible that scholars would all be better served by separating the question of credentialing from the publishing process, by allowing everything through the gate, by designing a post-publication peer review process that focuses on how a scholarly text should be received rather than whether it should be out there in the first place? Would the various credentialing bodies that currently rely on peer review’s gatekeeping function be satisfied if we were to say to them, “no, anonymous reviewers did not determine whether my article was worthy of publication, but if you look at the comments that my article has received, you can see that ten of the top experts in my field had really positive, constructive things to say about it”?

Nature‘s experiment is an honorable one, and a step in the right direction. It is, however, a conservative step, one that foregrounds the institutional purposes of peer review rather than the ways that such review might be made to better serve the scholarly community. We’ve been working this spring on what we imagine to be a more progressive possibility, the scholarly press reimagined not as a disseminator of discrete electronic texts, but instead as a network that brings scholars together, allowing them to publish everything from blogs to books in formats that allow for productive connections, discussions, and discoveries. I’ll be writing more about this network soon; in the meantime, however, if we really want to energize scholarly discourse through this new mode of networked publishing, we’re going to have to design, from the ground up, a productive new peer review process, one that makes more fruitful interaction among authors and readers a primary goal.

rosenzweig on wikipedia

Roy Rosenzweig, a history professor at George Mason University and colleague of the institute, recently published a very good article on Wikipedia from the perspective of a historian. “Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past” as a historian’s analysis complements the discussion from the important but different lens of journalists and scientists. Therefore, Rosenzweig focuses on, not just factual accuracy, but also the quality of prose and the historical context of entry subjects. He begins with in depth overview of how Wikipedia was created by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger and describes their previous attempts to create a free online encyclopedia. Wales and Sanger’s first attempt at a vetted resource, called Nupedia, sheds light on how from the very beginning of the project, vetting and reliability of authorship were at the forefront of the creators.

Rosenzweig adds to a growing body of research trying to determine the accuracy of Wikipedia, in his comparative analysis of it with other online history references, along similar lines of the Nature study. He compares entries in Wikipedia with Microsoft’s online resource Encarta and American National Biography Online out of the Oxford University Press and the American Council of Learned Societies. Where Encarta is for a mass audience, American National Biography Online is a more specialized history resource. Rosenzweig takes a sample of 52 entries from the 18,000 found in ANBO and compares them with entries in Encarta and Wikipeida. In coverage, Wikipedia contain more of from the sample than Encarta. Although the length of the articles didn’t reach the level of ANBO, Wikipedia articles were more lengthy than the entries than Encarta. Further, in terms of accuracy, Wikipedia and Encarta seem basically on par with each other, which confirms a similar conclusion (although debated) that the Nature study reached in its comparison of Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The discussion gets more interesting when Rosenzweig discusses the effect of collaborative writing in more qualitative ways. He rightfully notes that collaborative writing often leads to less compelling prose. Multiple stlyes of writing, competing interests and motivations, varying levels of writing ability are all factors in the quality of a written text. Wikipedia entries may be for the most part factually correct, but are often not that well written or historically relevant in terms of what receives emphasis. Due to piecemeal authorship, the articles often miss out on adding coherency to the larger historical conversation. ANBO has well crafted entries, however, they are often authored by well known historians, including the likes of Alan Brinkley covering Franklin Roosevelt and T. H. Watkins penning an entry on Harold Ickes.

However, the quality of writing needs to be balanced with accessibility. ANBO is subscription based, where as Wikipedia is free, which reveals how access to a resource plays a role in its purpose. As a product of the amateur historian, Rosenzweig comments upon the tension created when professional historians engage with Wikipedia. For example, he notes that it tends to be full of interesting trivia, but the seasoned historian will question its historic significance. As well, the professional historian has great concern for citation and sourcing references, which is not as rigorously enforced in Wikipedia.

Because of Wikipedia’s widespread and growing use, it challenges the authority of the professional historian, and therefore cannot be ignored. The tension is interesting because it raises questions about the professional historians obligation to Wikipedia. I am curious to know if Rosenzweig or any of the other authors of similar studies went back and corrected errors that were discovered. Even if they do not, once errors are published, an article quickly gets corrected. However, in the process of research, when should the researcher step in and make correction they discover? Rosenzweig documents the “burn out” that any experts feels when authors attempt to moderate of entries, including early expert authors. In general, what is the professional ethical obligation for any expert to engage maintaining Wikipedia? To this point, Rosenzweig notes there is an obligation and need to provide the public with quality information in Wikipedia or some other venue.

Rosenzweig has written a comprehensive description of Wikipedia and how it relates to the scholarship of the professional historian. He concludes by looking forward and describes what the professional historian can learn from open collaborative production models. Further, he notes interesting possibilities such as the collaborative open source textbook as well as challenges such as how to properly cite (a currency of the academy) collaborative efforts. My hope is that this article will begin to bring more historians and others in the humanities into productive discussion on how open collaboration is changing traditional roles and methods of scholarship.

nature re-jiggers peer review

Nature, one of the most esteemed arbiters of scientific research, has initiated a major experiment that could, if successful, fundamentally alter the way it handles peer review, and, in the long run, redefine what it means to be a scholarly journal. From the editors:

…like any process, peer review requires occasional scrutiny and assessement. Has the Internet bought new opportunities for journals to manage peer review more imaginatively or by different means? Are there any systematic flaws in the process? Should the process be transparent or confidential? Is the journal even necessary, or could scientists manage the peer review process themselves?

Nature’s peer review process has been maintained, unchanged, for decades. We, the editors, believe that the process functions well, by and large. But, in the spirit of being open to considering alternative approaches, we are taking two initiatives: a web debate and a trial of a particular type of open peer review.

The trial will not displace Nature’s traditional confidential peer review process, but will complement it. From 5 June 2006, authors may opt to have their submitted manuscripts posted publicly for comment.

In a way, Nature’s peer review trial is nothing new. Since the early days of the Internet, the scientific community has been finding ways to share research outside of the official publishing channels — the World Wide Web was created at a particle physics lab in Switzerland for the purpose of facilitating exchange among scientists. Of more direct concern to journal editors are initiatives like PLoS (Public Library of Science), a nonprofit, open-access publishing network founded expressly to undercut the hegemony of subscription-only journals in the medical sciences. More relevant to the issue of peer review is a project like arXiv.org, a “preprint” server hosted at Cornell, where for a decade scientists have circulated working papers in physics, mathematics, computer science and quantitative biology. Increasingly, scientists are posting to arXiv before submitting to journals, either to get some feedback, or, out of a competitive impulse, to quickly attach their names to a hot idea while waiting for the much slower and non-transparent review process at the journals to unfold. Even journalists covering the sciences are turning more and more to these preprint sites to scoop the latest breakthroughs.

Nature has taken the arXiv model and situated it within a more traditional editorial structure. Abstracts of papers submitted into Nature’s open peer review are immediately posted in a blog, from which anyone can download a full copy. Comments may then be submitted by any scientist in a relevant field, provided that they submit their name and an institutional email address. Once approved by the editors, comments are posted on the site, with RSS feeds available for individual comment streams. This all takes place alongside Nature’s established peer review process, which, when completed for a particular paper, will mean a freeze on that paper’s comments in the open review. At the end of the three-month trial, Nature will evaluate the public comments and publish its conclusions about the experiment.

A watershed moment in the evolution of academic publishing or simply a token gesture in the face of unstoppable change? We’ll have to wait and see. Obviously, Nature’s editors have read the writing on the wall: grasped that the locus of scientific discourse is shifting from the pages of journals to a broader online conversation. In attempting this experiment, Nature is saying that it would like to host that conversation, and at the same time suggesting that there’s still a crucial role to be played by the editor, even if that role increasingly (as we’ve found with GAM3R 7H30RY) is that of moderator. The experiment’s success will ultimately hinge on how much the scientific community buys into this kind of moderated semi-openness, and on how much control Nature is really willing to cede to the community. As of this writing, there are only a few comments on the open papers.

Accompanying the peer review trial, Nature is hosting a “web debate” (actually, more of an essay series) that brings together prominent scientists and editors to publicly examine the various dimensions of peer review: what works, what doesn’t, and what might be changed to better harness new communication technologies. It’s sort of a peer review of peer review. Hopefully this will occasion some serious discussion, not just in the sciences, but across academia, of how the peer review process might be re-thought in the context of networks to better serve scholars and the public.

(This is particularly exciting news for the Institute, since we are currently working to effect similar change in the humanities. We’ll talk more about that soon.)

another round: britannica versus wikipedia

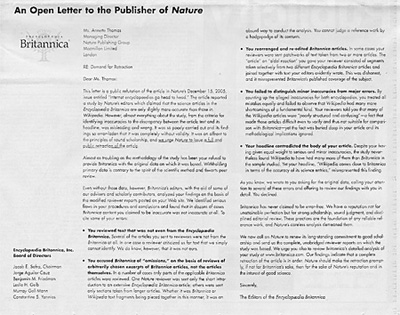

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

Several interesting things are going on here. Because Britannica chose to place an ad in the Times, it shifted the argument and debate away from the peer review / editorial context into one of rhetoric and public relations. Further, their conscious move to take the argument to the “public” or the “masses” with an open letter is ironic because the New York TImes does not display its print ads online, therefore access of the letter is limited to the Time’s print readership. (Not to mention, the letter is addressed to the Nature Publishing Group located in London. If anyone knows that a similar letter was printed in the UK, please let us know.) Readers here can click on the thumbnail image to read the entire text of the letter. Ben raised an interesting question here today, asking where one might post a similar open letter on the Internet.

Britannica cites many important criticisms of Nature’s article, including: using text not from Britannica, using excerpts out of context, giving equal weight to minor and major errors, and writing a misleading headline. If their accusations are true, then Nature should redo the study. However, to harp upon Nature’s methods is to miss the point. Britannica cannot do anything to stop Wikipedia, except to try to discredit to this study. Disproving Nature’s methodology will have a limited effect on the growth of Wikipedia. People do not mind that Wikipedia is not perfect. The JKF assassination / Seigenthaler episode showed that. Britannica’s efforts will only lead to more studies, which will inevitably will show errors in both encyclopedias. They acknowledge in today’s letter that, “Britannica has never claimed to be error-free.” Therefore, they are undermining their own authority, as people who never thought about the accuracy of Britannica are doing just that now. Perhaps, people will not mind that Britannica contains errors as well. In their determination to show the world that of the two encyclopedias which both content flaws, they are also advertising that of the two, the free one has some-what more errors.

In the end, I agree with Ben’s previous post that the Nature article in question has a marginal relevance to the bigger picture. The main point is that Wikipedia works amazingly well and contains articles that Britannica never will. It is a revolutionary way to collaboratively share knowledge. That we should give consideration to the source of our information we encounter, be it the Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia, Nature or the New York Time, is nothing new.

relentless abstraction

Quite surprisingly, Michael Crichton has an excellent op-ed in the Sunday Times on the insane overreach of US patent law, the limits of which are to be tested today before the Supreme Court. In dispute is the increasingly common practice of pharmaceutical companies, research labs and individual scientists of patenting specific medical procedures or tests. Today’s case deals specifically with a basic diagnostic procedure patented by three doctors in 1990 that helps spot deficiency in a certain kind of Vitamin B by testing a patient’s folic acid levels.

Quite surprisingly, Michael Crichton has an excellent op-ed in the Sunday Times on the insane overreach of US patent law, the limits of which are to be tested today before the Supreme Court. In dispute is the increasingly common practice of pharmaceutical companies, research labs and individual scientists of patenting specific medical procedures or tests. Today’s case deals specifically with a basic diagnostic procedure patented by three doctors in 1990 that helps spot deficiency in a certain kind of Vitamin B by testing a patient’s folic acid levels.

Under current laws, a small royalty must be paid not only to perform the test, but to even mention it. That’s right, writing it down or even saying it out loud requires payment. Which means that I am in violation simply for describing it above. As is the AP reporter whose story filled me in on the details of the case. And also Michael Crighton for describing the test in his column (an absurdity acknowledged in his title: “This Essay Breaks the Law”). Need I (or may I) say more?

And patents can reach far beyond medical procedures that prevent diseases. They can be applied to the diseases themselves, even to individual genes. Crichton:

…the human genome exists in every one of us, and is therefore our shared heritage and an undoubted fact of nature. Nevertheless 20 percent of the genome is now privately owned. The gene for diabetes is owned, and its owner has something to say about any research you do, and what it will cost you. The entire genome of the hepatitis C virus is owned by a biotech company. Royalty costs now influence the direction of research in basic diseases, and often even the testing for diseases. Such barriers to medical testing and research are not in the public interest. Do you want to be told by your doctor, “Oh, nobody studies your disease any more because the owner of the gene/enzyme/correlation has made it too expensive to do research?”

It seems everything — even “laws of nature, natural phenomena and abstract ideas” (AP) — is information that someone can own. It goes far beyond the digital frontiers we usually talk about here. Yet the expansion of the laws of ownership — what McKenzie Wark calls “the relentless abstraction of the world” — essentially digitizes everything, and everyone.

nature magazine says wikipedia about as accurate as encyclopedia brittanica

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did something similar, though less formal, a couple of months back — read the first comment). According to an article published today:

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did something similar, though less formal, a couple of months back — read the first comment). According to an article published today:

Entries were chosen from the websites of Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica on a broad range of scientific disciplines and sent to a relevant expert for peer review. Each reviewer examined the entry on a single subject from the two encyclopaedias; they were not told which article came from which encyclopaedia. A total of 42 usable reviews were returned out of 50 sent out, and were then examined by Nature’s news team. Only eight serious errors, such as misinterpretations of important concepts, were detected in the pairs of articles reviewed, four from each encyclopaedia. But reviewers also found many factual errors, omissions or misleading statements: 162 and 123 in Wikipedia and Britannica, respectively.

It’s interesting to see Nature coming to the defense of Wikipedia at the same time that so many academics in the humanities and social science have spoken out against it: it suggests that the open source culture of academic science has led to a greater tolerance for Wikipedia in the scientific community. Nature’s reviewers were not entirely thrilled with Wikipidia: for example, they found the Britannica articles to be much more well-written and readable. But they also noted that Britannica’s chief problem is the time and effort it takes for the editorial department to update material as a scientific field evolves or changes: Wikipedia updates often occur practically in real time.

One not-so-suprising fact unearthed by Nature’s staffers is that the scientific community contained about twice as many Wikipedia users as Wikipedia authors. The best way to ensure that the science in Wikipedia is sound, the magazine argued, is for scientists to commit to writing about what they know.