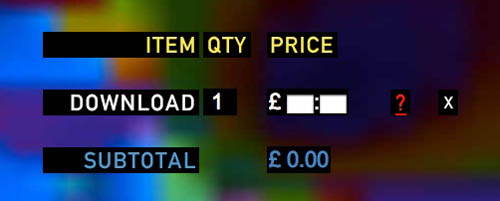

To fans long famished for a new Radiohead album (we’ve been waiting since ’03, with an admittedly lovely Thom Yorke solo effort last year to tide us over), there came today some very welcome news: their latest record, “In Rainbows,” is due to be released October 10th (hallelujah!). What’s worth noting here is how they’re doing it. With the release of their “COM LAG” EP in 2004, a collection of mainly b-sides from “Thief,” Radiohead wrapped up a 6-record contract with EMI. Rather than renewing or seeking a deal with another label, the band bucked the industry, opting to take charge of its own distribution. Well today they announced their first major act as their own boss, a simple website where you can pre-order (and soon purchase) their new album in two forms: 1) a beautiful collector’s discbox (pictured above) containing a CD (with bonus tracks and digital photos), two vinyl records, artwork and lyric booklets, all “encased in a hardback book and slipcase”; and 2) a digital download. Price of the discbox is 40 British pounds. Price of the download: it’s up to you.

Clearly, the band figures that these days mp3s fall more in the gift economy sector of making and distributing music. The big money is to be made off of touring, or, to a lesser degree, through the sale of lovingly crafted physical artifacts packed with all the juicy supplemental stuff that fans revel in. But yes, it’s true: a small transaction fee notwithstanding, the download can theoretically be obtained for nothing. I expect, though, that this good faith gesture might predispose fans (including this one) to voluntarily cough up 5 to 10 bucks (or rather, quid). It’s a very cool move on Radiohead’s part, one that acknowledges the fact that valuation of digital media is today very much an open question, and that figuring out the answer is best done not by the industries but through dialogue between the makers and the listeners (and all those folks in between).

Click the ?:

Another quick thought: by offering a pay-what-you-want download of the entire album, Radiohead is in a way cleverly pushing back the larger trend in music buying/sharing/pirating of disaggregation: i.e. tracks as the fundamental unit rather than whole records. They’re one of those bands whose music still justifies the album form and is crafted to fit that shape. Naturally they’ll do what they can to ensure that people experience it that way.

Category Archives: mp3

the life and afterlife of vinyl records

I often find myself talking to people about their relationships to books and printed matter. I wonder out loud, if we are the transitional (read: last) generation who will revere both print and screen. Because books have been the primary mode of storing and communicating knowledge for over five hundred years, we have a strong attachment to print text. The shift to from the page to the digital, and all its implications are difficult to grasp. Through these conversations, I have found that modern recorded music and especially the vinyl record, are useful cultural reference points for myself and others in understanding how media technology evolves and our preferences with it. For people born before, say the Reagan administration, they mostly likely have bought and used a variety of recorded music media, including vinyl records and audio cassette tapes. Further, they generally know people born during or after the Reagan administration who have never played, owned and even heard a LP record. This point demonstrates how we have witnessed the conversion of media technology from the analogue to the digital. Further, we can clearly see a subsequent generation who has a very different relationship to recorded music, rooted in a solely digital frame of reference.

The evolution and adoption of recorded music technology have occurred over a compressed period of time as compared to the historic primacy of the book. Early movable type was available in China in the 11th century. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century gives print a legacy that dwarfs the 20th century dominance of the vinyl record. It is not surprising that print is more entrenched in our culture. The vinyl record was able to be inexpensively mass produced, although vinyl records were fragile and their players were not easily transportable. New media technologies and formats appeared. In one case, the audio cassette tape complemented the LP, because the format and player was smaller and portable, and you could also make recordings on them. In another case of the digital CD, LPs were replaced because CDs had higher quality sound and did not scratch as easily as vinyl. We should also note that some technologies failed, such as the 8 track, which did not gain traction and faded to the background of ironic 70s pop culture references. This reminds us that we need to take each “next great” invention with a healthy bit of skepticism. Because the transitions from LPs to CDs and now to MP3s occurred in a span of twenty years, we have the benefit of living through the shifts. Therefore, the transition is less disconcerting even if its transition is not complete or fully understood. The current shift from CD to MP3 introduces us to a host of transitional issues that we will soon face with print books.

With the MP3, recorded music no longer has a physical form, just as digital text no longer embodies the physical page. Music’s transition from the analogue to the digital is far from complete. Musicians, distributors, and listeners are still adapting to the changes that going digital is causing. Musicians have new methods of recording and are experimenting with new ways reaching their audiences. Distributors of music are struggling to develop new business models in the digital, online and networked world. Listeners have a new relationship with music, now that they can access their entire music collection from an iPod. Music’s pioneering shift to the digital shows what lies ahead for the digital book in many ways. For example, we are learning from initial applications of DRM, including Apple restrictions on songs bought in the iTunes Music Store, Sony’s disastrous attempt to deploy its DRM Rootkit and Sun’s Open DRM initiatives. Some ideas will work, and some will not. These early implementations of DRM will certainly inform how it is applied to digital texts.

|

|

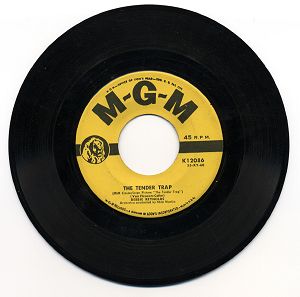

We can also see how the aspects of these older forms reappear in interesting ways. This continuity removes some of the disorientation that occurs in any period of transition. In middle school, I bought my first 45 single, the theme song from Beverly Hills Cop, “Axel F” by Harold Faltermeyer. As a format, the 45 single had its height of popularity in the 50s and 60s. In the 1970s, recording industry shifted their focus on creating and promoting album-oriented music. Today, the emergence of the MP3 music file marked the return of the single. As the preferred format for buying and downloading MP3s, tastes have cycled back to popularize the single in a digital form. Further, we maintain our nostalgia for the plastic insert that 45s required to be able to be played on LP record players. Nostalgia and forms reappearing is a common occurrence in the evolution of media.

Likewise, despite the fact that the LP is no longer as widely produced and used as it once was, it still has cultural relevance. Looking at the LP shows glimpses of a possible future for the print book in the digital age. One future of the print book, which Bob has mentioned, is the book as art object. This transformation is being foretold by the transformation of the vinyl LP as art object. The vinyl LP for newly recorded music is now a niche market. The only people I know, who still actively purchase vinyl records are DJs and indie rock purists. For the rest of us, we have moved on to CDs and MP3s. I have not owned a record player in years. However, if you go into my bedroom, you will see LPs prominently displayed. I have two (different) original “Beyond the Fringe” cast recordings of LPs hanging on my wall. Within these frames, the vinyl record is now an art object. Partially because the CD jewel box is much smaller, the LP is able to leverage its size and proportion of its record cover to maintain relevance of an cultural artifact. The Equator Bookstore in Los Angeles has taken a similar attitude towards the book. Their website explains that “all books are hand-picked by ownership and are sold in collectable condition, cleaned and wrapped in protective archival covering.” Thus, the owners are curating a collection of archival objects. They sell books as art objects, akin to the records hanging on my walls. (Although, interestingly, they also have a small publishing arm, which suggests that they are interested in publishing the book art object of the future.)

Because we have seen a radical shift in the ways people listen to music within our own lifetime, we can apply this experience to our understanding of the older, more entrenched and slower to adapt form of the book. Through this process, we see that we will maintain our attachments to older forms of media. Through nostalgia, transformation, repurposing of these beloved forms, a legacy is sustained. This occurrence should come as no surprise, as media, technology and culture has always been built upon older iterations of itself.

vive le interoperability!

A smart column in Wired by Leander Kahney explains why France’s new legislation prying open the proprietary file format lock on iPods and other entertainment devices is an important stand taken for the public good:

A smart column in Wired by Leander Kahney explains why France’s new legislation prying open the proprietary file format lock on iPods and other entertainment devices is an important stand taken for the public good:

French legislators aren’t just looking at Apple. They’re looking ahead to a time when most entertainment is online, a shift with profound consequences for consumers and culture in general. French lawmakers want to protect the consumer from one or two companies holding the keys to all of its culture, just as Microsoft holds the keys to today’s desktop computers.

Apple, by legitimizing music downloading with iTunes and the iPod, has been widely credited with making the internet safe for the culture industries after years of hysteria about online piracy. But what do we lose in the bargain? Proprietary formats lock us into specific vendors and specific devices, putting our media in cages. By cornering the market early, Apple is creating a generation of dependent customers who are becoming increasingly shackled to what one company offers them, even if better alternatives come along. France, on the other hand, says let everything be playable on everything. Common sense says they’re right.

Now Apple is the one crying piracy, calling France the great enabler. While I agree that piracy is a problem if we’re to have a functioning cultural economy online, I’m certain that proprietary controls and DRM are not the solution. In the long run, they do for culture what Microsoft did for software, creating unbreakable monopolies and placing unreasonable restrictions on listeners, readers and viewers. They also restrict our minds. Just think of the cumulative cognitive effect of decades of bad software Microsoft has cornered us into using. Then look at the current ipod fetishism. The latter may be more hip, but they both reveal the same narrowed thinking.

One thing I think the paranoid culture industries fail to consider is that piracy is a pain in the ass. Amassing a well ordered music collection through illicit means is by no means easy — on the contrary, it can be a tedious, messy affair. Far preferable is a good online store selling mp3s at reasonable prices. There you can find stuff quickly, be confident that what you’re getting is good and complete, and get it fast. Apple understood this early on and they’re still making a killing. But locking things down in a proprietary format takes it a step too far. Keep things open and may the best store/device win. I’m pretty confident that piracy will remain marginal.

LONGPLAYER

when i was growing up they started issuing LP albums which played at 33 1/3 rpm, vastly increasing the amount of playing time on one side of a record. before the LP, audio was recorded and distributed on brittle discs made of shellac, running at 78rpm. 78s had a capacity of about 12 minutes; LPs upped that to about 30 minutes which made it possible for classical music fans to listen to an entire movement without changing discs and enabled  the development of the rock and roll album.

the development of the rock and roll album.

in 2,000 Jem Finer, a UK-based artist released Longplayer, a 1000-year musical composition that runs continuously and without repetition from its start on January 1, 2000 until its completion on December 31, 2999. Related conceptually to the Long Now project which seeks to build a ten-thousand year clock, Longplayer uses generative forms of music to make a piece that plays for ten to twelve human lifetimes. Longplayer challenges us to take a longer view which takes account of the generations that will come after us.

the longplayer also reminds me of an idea i’ve been intrigued by — the possiblity of (networked) books that never end because authors keep adding layers, tangents and new chapters.

Finer published a book about Longplayer which includes a vinyl disc (LP actually) with samples.

the poetry archive – nice but a bit mixed up

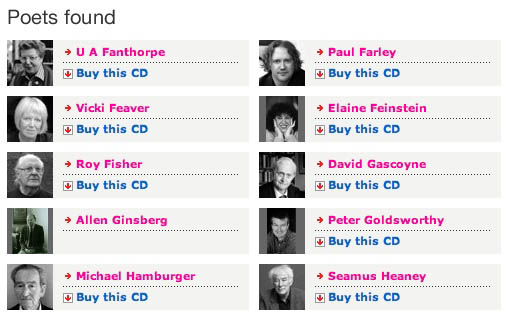

Last week U.K. Poet Laureate Andrew Motion and recording producer Richard Carrington rolled out The Poetry Archive, a free (sort of) web library that aims to be “the world’s premier online collection of recordings of poets reading their work” — “to help make poetry accessible, relevant and enjoyable to a wide audience.”  The archive naturally focuses on British poets, but offers a significant selection of english-language writers from the U.S. and the British Commonwealth countries. Seamus Heaney is serving as president of the archive.

The archive naturally focuses on British poets, but offers a significant selection of english-language writers from the U.S. and the British Commonwealth countries. Seamus Heaney is serving as president of the archive.

For each poet, a few streamable mp3s are available, including some rare historic recordings dating back to the earliest days of sound capture, from Robert Browning to Langston Hughes. The archive also curates a modest collection of children’s poetry, and invites teachers to use these and other recordings in the classroom, also providing tips for contacting poets so schools, booksellers and community organizations (again, this is focused on Great Britain) can arrange readings and workshops. While some of this advice seems useful, but it reads more like a public relations/ecudation services page on a publisher’s website. Is this a public archive or a poets’ guild?

The Poetry Archive is a nice resource as both historic repository and contemporary showcase, but the mission seems a bit muddled. They say they’re an archive, but it feels more like a CD store.

Throughout, the archive seems an odd mix of public service and professional leverage for contemporary poets. That’s all well and good, but it could stand a bit more of the former. Beyond the free audio offerings (which are quite skimpy), CDs are available for purchase that include a much larger selection of recordings. The archive is non-profit, and they seem to be counting in significant part on these sales to maintain operations. Still, I would add more free audio, and focus on selling individual recordings and playlists as downloads — the iTunes model. Having streaming teasers and for-sale CDs as the only distribution models seems wrong-headed, and a bit disingenuous if they are to call themselves an archive. It would also be smart to sell subscriptions to the entire archive, with institutional rates for schools. Podcasting would also be a good idea — a poem a day to take with you on your iPod, weaving poetry into daily life.

There’s a growing demand on the web for the spoken word, from audiobooks, podcasts, to performed poetry. The archive would probably do a lot better if they made more of their collection free, and at the same time provided a greater variety of ways to purchase recordings.

playaways hit the market

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

I’m a bit puzzled by the Playaways. I can understand why publishing industry executives would be excited about them, but I’m not so about consumers. The self-contained players are being marketed to an audience that wants an audiobook but doesn’t want to be bothered with CD or MP3 players. The happy customers pictured on the Playaway website are both young and middle aged, but I suspect the real audience for these players would be older Americans who have sworn off computer literacy, and I don’t know that these folks are listening to audio books through headphones.

Speaking of older Americans, if you go down into my parent’s basement, you’ll see a few big shopping bags of books-on-tape that they bought, listened to once, and then found too expensive to throw out yet impossible to give away. This seems clearly to be the future of the Playaways, which can be listened to repeatedly (if you keep changing the batteries) but can’t play anything else than the book they were intended to play. The throwaway nature of the Playaway (suggested, of course, by the very name of the device) is addressed on the company’s website, which provides helpful suggestions on how to get rid of the things once you don’t want ’em anymore. According to the website, you can even ask the Playaway people to send you a stamped envelope addressed to a charitable organization that would be happy to take your Playaway.

This begs the obvious question: what if that organization wants to get rid of the Playway? And so on?

How many times will Playaway shell out a stamp to keep their players out of the landfill?