The institute is pleased to announce the release of the blog Without Gods. Mitchell Stephens is using this blog as a public workshop and forum for his work on his latest book which focuses on the history of atheism.

The wikipedia debate continues as Chris Anderson of Wired Magazine weighs in that people are uncomfortable with wikipedia because they cannot comprehend that emergent systems can produce “correct” answers on the marcoscale even if no one is really watching the microscale. Lisa poses that Anderson goes too far in the defense of wikipedia and that blind faith in the system is equally disconcerting, if not more so.

ITP Winter 2005 show had several institute related projects. Among them were explorations in digital graphic reinterpretation of poetry, student social networks, navigating New York through augmented reality, and manipulating video to document the city by freezing time and space.

Lisa discovered an interesting historical parallel in an article from Dial dating back to 1899. The specialized bookseller’s demise is lamented with the introduction of department store selling books as lost leader, not unlike today’s criticisms of Amazon. As libraries are increasing their relationships with the private sector, Lisa notes that some bookstores are playing a role in fostering intellectual and culture communities, a role which libraries traditionally held.

Lisa looked at Reed Johnson assertion in the Los Angeles Times that 2005 was the year that mass media has given way to the consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution.

The discourse on game space continues to evolve with Edward Castronova’s new book Synthetic Worlds. As millions of people spend more time in the immersive environments, Castronova looks at how the real and the virtual are blending through the lens of an economist.

In another advance for content creation volunteerism, LibriVox is creating and distributing audio files of public domain literature. Ranging from the Wizard of Oz to the US Constitution, Lisa was impressed by the quality of the recordings, which are voiced and recorded by volunteers who feel passionate about a particular work.

Category Archives: libraries

the future of the book(store), circa 1899 and 2005

Leafing through an 1899 issue of the literary magazine The Dial, I came across an article called “The Distribution of Books” which resonated with the present moment at several uncanny junctures, and got me thinking about the evolving relationship between publishers, libraries, bookstores, and Google Book Search — thoughts which themselves evolved after a conversation with a writer from Pages magazine about the future of bookstores.

“The Distribution of Books” focused mainly on changes in the way books were marketed and distributed, warning that bookstores might go out of business if they failed to change their own business practices in response. “Once more the plaint of the bookseller is heard in the land,” lamented the author, “and one would be indeed stony-hearted who could view his condition without concern.”

According to “The Distribution of Books,” what should have been the privileged domain of the bookseller was being eroded at the century’s end by the book sales of “the great dealers in miscellaneous merchandise.” The article was referring to the department stores that sold books at a loss in order to lure in customers: a bit less than a century later, critics would make the same claims about Amazon, that great dealer in miscellaneous merchandise now celebrating its tenth anniversary. “The Distribution of Books” also complains of the direct marketing practices of publishers who attempted to market to readers directly. This past year, similar complaints were made after Random House joined Scholastic and Simon and Schuster this year in establishing a direct-sale online presence.

Of course, 2005 is not 1899, and this is what makes the Dial piece so startling in its familiarity: in 1899, after all, the distinction between publisher and bookseller was much fresher than now. Hybrid merchant/tradesman who printed, marketed and distributed books at the same time had been the norm for a much longer interval than the shop owner who ordered books from a variety of different publishing houses. In this sense, the publisher’s “new” practice of selling books directly was in fact a modification of bookselling practices that predated the specialized bookshop. Ultimately, the Dial piece is less about the demise of the bookseller than about the imagined demise of a relatively recent phenomenon — the specialized book seller with an investment in promoting the culture of books generally rather than the work of a specific author or publisher.

This tension between specialization and generalization also revealed itself in the article’s most indignant passage, in which the author expressed outrage over the idea that libraries might themselves get involved in bookselling. According to the Dial, bookstore owners had been subjected to:

an onslaught so unexpected and so startling it left [them] gasping for breath — [a suggestion] made a few months ago by librarian Dewey, who calmly proposed that the public libraries throughout the country should be book-selling as well as book-circulating agencies… Booksellers have always looked askance at public libraries, not understanding how they create an appetite for reading that is sure in the end to redound to the bookseller’s advantage, but their suspicious fears never anticipated the explosion in their camp of such a bombshell as this.

After delivering the “bombshell,” the author goes on to reassure the reader that Dewey’s suggestion (yes, that would be Melvil Dewey, inventor of the Dewey Decimal System) could never be taken seriously in America: such a venture on the part of the nation’s libraries would represent a socialistic entangling of the spheres of government and industry. Books sold by libraries would be sold without an eye to profit, conjectured the author, and publishing —-and perhaps the notion of the private sector itself — would collapse. “If the state or the municipality were to go into the business of selling books at cost, what should prevent it from doing the like with groceries?”

While the Dial piece made me think about the ways in which the perceived “new” threats to today’s bookstores might not be so new, it also made me consider how Dewey’s proposal might emerge in modified form in the digital era. While present-day libraries haven’t been proposing the sale of books, they certainly are planning to get into the business of marketing and distribution, as the World Digital Library attests. They are also proposing, as Librarian of Congress librarian James Billington has said, a shift toward significant partnerships with for-profit businesses which have (for various reasons) serious economic stakes in sifting through digital materials. And, as Ben noted a few weeks ago, libraries themselves have been using various strategies from online retailers to catalog and present information.

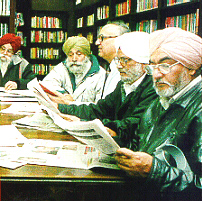

Just as libraries are starting to embrace the private sector, many bookstores are heading in the other direction: driven to the verge of extinction by poor profits, they are reinventing themselves as nonprofits that serve a valuable social and cultural function. Sure, books are still for sale, but the real “value” of a bookstore is now lies not in its merchandise, but in the intellectual or cultural community it fosters: in that respect, some bookstores are thus akin to the subscription libraries of the past.

Is it so impossible to imagine a future in which one walks into a digital distribution center, orders a latte, and uses an Amazon-type search engine to pull up the ebook that can be read at one’s reading station after the requisite number of ads have flashed on the screen? Is this a library? Is this a bookstore? Does it matter? Should it?

more on wikipedia

As summarized by a Dec. 5 article in CNET, last week was a tough one for Wikipedia — on Wednesday, a USA today editorial by John Seigenthaler called Wikipedia “irresponsible” for not catching significant mistakes in his biography, and Thursday, the Wikipedia community got up in arms after discovering that former MTV VJ and longtime podcaster Adam Curry had edited out references to other podcasters in an article about the medium.

In response to the hullabaloo, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales now plans to bar anonymous users from creating new articles. The change, which went into effect today, could possibly prevent a repeat of the Seigenthaler debacle; now that Wikipedia would have a record of who posted what, presumably people might be less likely to post potentially libelous material. According to Wales, almost all users who post to Wikipedia are already registered users, so this won’t represent a major change to Wikipedia in practice. Whether or not this is the beginning of a series of changes to Wikipedia that push it away from its “hive mind” origins remains to be seen.

I’ve been surprised at the amount of Wikipedia-bashing that’s occurred over the past few days. In a historical moment when there’s so much distortion of “official” information, there’s something peculiar about this sudden outrage over the unreliability of an open-source information system. Mostly, the conversation seems to have shifted how people think about Wikipedia. Once an information resource developed by and for “us,” it’s now an unreliable threat to the idea of truth imposed on us by an unholy alliance between “volunteer vandals” (Seigenthaler’s phrase) and the outlaw Jimmy Wales. This shift is exemplified by the post that begins a discussion of Wikipedia that took place over the past several days on the Association of Internet Researchers list serve. The scholar who posted suggested that researchers boycott Wikipedia and prohibit their students from using the site as well until Wikipedia develops “an appropriate way to monitor contributions.” In response, another poster noted that rather than boycotting Wikipedia, it might be better to monitor for the site — or better still, write for it.

Another comment worthy of consideration from that same discussion: in a post to the same AOIR listserve, Paul Jones notes that in the 1960s World Book Encyclopedia, RCA employees wrote the entry on television — scarcely mentioning television pioneer Philo Farnsworth, longtime nemesis of RCA. “Wikipedia’s failing are part of a public debate,” Jones writes, “Such was not the case with World Book to my knowledge.” In this regard, the flak over Wikipedia might be considered a good thing: at least it gives those concerned with the construction of facts the opportunity to debate with the issue. I’m just not sure that making Wikipedia the enemy contributes that much to the debate.

sober thoughts on google: privatization and privacy

Siva Vaidhyanathan has written an excellent essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education on the “risky gamble” of Google’s book-scanning project — some of the most measured, carefully considered comments I’ve yet seen on the issue. His concerns are not so much for the authors and publishers that have filed suit (on the contrary, he believes they are likely to benefit from Google’s service), but for the general public and the future of libraries. Outsourcing to a private company the vital task of digitizing collections may prove to have been a grave mistake on the part of Google’s partner libraries. Siva:

The long-term risk of privatization is simple: Companies change and fail. Libraries and universities last…..Libraries should not be relinquishing their core duties to private corporations for the sake of expediency. Whichever side wins in court, we as a culture have lost sight of the ways that human beings, archives, indexes, and institutions interact to generate, preserve, revise, and distribute knowledge. We have become obsessed with seeing everything in the universe as “information” to be linked and ranked. We have focused on quantity and convenience at the expense of the richness and serendipity of the full library experience. We are making a tremendous mistake.

This essay contains in abundance what has largely been missing from the Google books debate: intellectual courage. Vaidhyanathan, an intellectual property scholar and “avowed open-source, open-access advocate,” easily could have gone the predictable route of scolding the copyright conservatives and spreading the Google gospel. But he manages to see the big picture beyond the intellectual property concerns. This is not just about economics, it’s about knowledge and the public interest.

What irks me about the usual debate is that it forces you into a position of either resisting Google or being its apologist. But this fails to get at the real bind we all are in: the fact that Google provides invaluable services and yet is amassing too much power; that a private company is creating a monopoly on public information services. Sooner or later, there is bound to be a conflict of interest. That is where we, the Google-addicted public, are caught. It’s more complicated than hip versus square, or good versus evil.

Here’s another good piece on Google. On Monday, The New York Times ran an editorial by Adam Cohen that nicely lays out the privacy concerns:

Google says it needs the data it keeps to improve its technology, but it is doubtful it needs so much personally identifiable information. Of course, this sort of data is enormously valuable for marketing. The whole idea of “Don’t be evil,” though, is resisting lucrative business opportunities when they are wrong. Google should develop an overarching privacy theory that is as bold as its mission to make the world’s information accessible – one that can become a model for the online world. Google is not necessarily worse than other Internet companies when it comes to privacy. But it should be doing better.

Two graduate students in Stanford in the mid-90s recognized that search engines would the most important tools for dealing with the incredible flood of information that was then beginning to swell, so they started indexing web pages and working on algorithms. But as the company has grown, Google’s admirable-sounding mission statement — “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” — has become its manifest destiny, and “information” can now encompass the most private of territories.

At one point it simply meant search results — the answers to our questions. But now it’s the questions as well. Google is keeping a meticulous record of our clickstreams, piecing together an enormous database of queries, refining its search algorithms and, some say, even building a massive artificial brain (more on that later). What else might they do with all this personal information? To date, all of Google’s services are free, but there may be a hidden cost.

“Don’t be evil” may be the company motto, but with its IPO earlier this year, Google adopted a new ideology: they are now a public corporation. If web advertising (their sole source of revenue) levels off, then investors currently high on $400+ shares will start clamoring for Google to maintain profits. “Don’t be evil to us!” they will cry. And what will Google do then?

images: New York Public Library reading room by Kalloosh via Flickr; archive of the original Google page

virtual libraries, real ones, empires

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Libraries are inherently islands of freedom and antidotes to fanaticism. They are temples of pluralism where books that contradict one another stand peacefully side by side just as intellectual antagonists work peacefully next to each other in reading rooms. It is legitimate and in our nation’s interest that the new technology be used internationally, both by the private sector to promote economic enterprise and by the public sector to promote democratic institutions. But it is also necessary that America have a more inclusive foreign cultural policy — and not just to blunt charges that we are insensitive cultural imperialists. We have an opportunity and an obligation to form a private-public partnership to use this new technology to celebrate the cultural variety of the world.

What’s interesting about this quote (among other things) is that Billington seems to be suggesting that a World Digital Library would function in much the same manner as a real-world library, and yet he’s also arguing for the importance of actual physical proximity. He writes, after all, about books literally, not virtually, touching each other, and about researchers meeting up in a shared reading room. There seems to be a tension here, in other words, between Billington’s embrace of the idea of a world digital library, and a real anxiety about what a “library” becomes when it goes online.

I also feel like there’s some tension here — in Billington’s editorial and in the whole World Digital Library project — between “inclusiveness” and “imperialism.” Granted, if the United States provides Brazilians access to their own national literature online, this might be used by some as an argument against the idea that we are “insensitive cultural imperialists.” But there are many varieties of empire: indeed, as many have noted, the sun stopped setting on Google’s empire a while ago.

To be clear, I’m not attacking the idea of the World Digital Library. Having watch the Smithsonian invest in, and waffle on, some of their digital projects, I’m all for a sustained commitment to putting more material online. But there needs to be some careful consideration of the differences between online libraries and virtual ones — as well as a bit more discussion of just what a privately-funded digital library might eventually morph into.

books behind bars – the Google library project

How useful will this service be for in-depth research when copyrighted books (which will account for a huge percentage of searchable texts) cannot be fully accessed? In such cases, a person will be able to view only a selection of pages (depending on agreements with publishers), and will find themselves bombarded with a variety of retail options. On a positive note, the search will be able to refer the user to any local libraries where the desired book is available, but still, the focus here remains squarely on digital texts as simply a means of getting to print texts.

Absent a major paradigm shift with regard to the accessibility and inherent virtue of electronic texts, this ambitious project will never achieve its full potential. For someone searching outside the public domain, the Google library project may amount to nothing more than a guided tour through a prison of incarcerated texts. I’ve found this to be true so far with Google Scholar – it turned up a lot of interesting stuff, but much of it was password protected or required purchase.

article in Filter: Google — 21st Century Dewey Decimal System (washingtonpost.com)

NYPL ebook collection leaves much to be desired

I just checked out two titles from the New York Public Library’s ebook catalog, only to learn, to my great astonishment, that those books are now effectively “checked out,” and cannot be downloaded again by anyone else until my copies time out.

It boggles the mind that NYPL would go to the trouble of establishing a collection of electronic titles, only to wipe out every advantage offered by digital texts. In fact, they do more than simply keep the ebooks on the level of print, they limit them further than that, since there are generally multiple copies of most print titles in the NYPL system.

The people responsible for this catalog have either entirely failed to grasp the concept of infinitely accessible, screen-based books, or they grasp it all too well and are trying to stunt it at its inception, perhaps out of fear of extinction of the print librarian. More likely, they are under heavy pressure by a paranoid copyright regime. Whatever the reason, the new ebook catalog shows a total lack of imagination and offers nearly no tangible benefit for the reader.

Beyond that, the books themselves are poorly designed and unpleasant to read. My downloaded copy of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (which, by the way, I found in the “Romance” section) evidences no more than ten minutes worth of design work, and appears to be simply a cut-and-pasted ASCII file from Gutenberg with a garish graphic slapped on the cover. My copy of Chain of Command by Seymour Hersh was a bit more respectable – more or less a pdf facsimile of the print edition.

On an amusing note, the “literary criticism” section is populated almost entirely by Cliff’s Notes.