In ten years, the world wide web has become an indispensable fact of life. Where do we take it next? At the conference’s closing plenary session, Peter Lunenfeld asked a similar question: “What is the next big dream that will keep us going? Are we out of ideas?” He then offered something called “urban computing” as a possible answer.

Here is my attempt (rather long, I apologize) to jump on that dream…

I live in New York, and in the past few years I’ve observed a transformation. My neighborhood coffee shop looks like an advertisement for Apple. At any given time, no less than two thirds of the customers are glued to their laptops, with mugs of coffee steaming in perilous proximity.  Power cords snake among the tables and plug into strips deployed around the cafe floor. Go to the counter and they’ll be happy to give you a dog-eared business card bearing the password to their wireless network. Of course, people have been toting around notebook computers since they first became available in the mid-80s, and they’ve certainly been no stranger to coffee shops. But with the introduction of Wi-Fi people are flocking in droves. Some kind of exodus has begun.

Power cords snake among the tables and plug into strips deployed around the cafe floor. Go to the counter and they’ll be happy to give you a dog-eared business card bearing the password to their wireless network. Of course, people have been toting around notebook computers since they first became available in the mid-80s, and they’ve certainly been no stranger to coffee shops. But with the introduction of Wi-Fi people are flocking in droves. Some kind of exodus has begun.

It’s a familiar sight throughout the more cosmopolitan neighborhoods of the city. Go to any Starbucks on the Upper West Side and you’re competing with half a dozen other customers for a space on their too-few powerstrips. And their Wi-Fi service isn’t even free. And come spring, I predict the same will occur in the city’s parks, especially those downtown, which are rapidly being integrated into a massive wireless infrastructure. No single entity is responsible for this, rather a lattice of different initiatives working toward a common goal: free high speed Wi-Fi coverage across Manhattan.

Mobile web and messaging technologies have already created a new breed of roving web users. Cell phones, PDAs, text messaging, Blue Tooth, RSS, podcasting (the list goes on..) have swept into our daily life like a tidal wave. More and more, we’re able to read, search, capture, edit, and send on the go, and with satellite-fed positioning technologies, we can pinpoint our location at any given time. What we have is the beginnings of a kind of “augmented reality” where information relates intimately to place, and vice versa. The world itself can now be as searchable, linkable, and informative as the web – a synthesis, or overlay, of real and virtual realities.

So the next big dream could be the evolution of the web into something more than a desktop system – into something that we can use while moving, and interact with anywhere.

Category Archives: Libraries, Search and the Web

collecting and archiving the future book

The collection and preservation of digital artworks has been a significant issue for museum curators for many years now. The digital book will likely present librarians with similar challenges, so it seems useful to look briefly at what curators have been grappling with.

At the Decade of Web Design Conference hosted by the Institute for Networked Cultures. Franziska Nori spoke about her experience as researcher and curator of digital culture for digitalcraft at the Museum for Applied Art in Frankfurt am Main. The project set out to document digital craft as a cultural trend. Digital crafts were defined as “digital objects from everyday life,” mostly websites. Collecting and preserving these ephemeral, ever-changing objects was difficult, at best. A choice had to be made between manual selection, or automatic harvesting. Nori and her associates chose manual selection. The advantage of manual selection was that critical faculties could be employed. The disadvantage was that subjective evaluations regarding an object’s relevance were not always accurate, and important work might be left out. If we begin to treat blogs, websites, and other electronic ephemera as cultural output worthy of preservation and study (i.e. as books), we will have to find solutions to similar problems.

The pace at which technology renews and outdates presents a further obstacle. There are, currently, two ways to approach durability of access to content. The first, is to collect and preserve hardware and software platforms, but this is extremely expensive and difficult to manage. The second solution, is to emulate the project in updated software. In some cases, the artist must write specs for the project, so it can be recreated at a later date. Both these solutions are clearly impractical for digital librarians who must manage hundreds of thousand of objects. One possible solution for libraries, is to encourage proliferation of objects. Open source technology might make it possible for institutions to share data/objects, thus creating “back-up” systems for fragile digital archives.

Nori ended her presentation with two observations. “Most societies create their identity through an awareness of their history.” This, she argues, compells us to find ways to preserve digital communications for posterity. She notes that cultural historians, artists, and researchers “are worried about a future where these artifacts will not be accessible.”

from aspen to A9

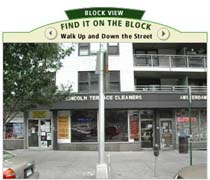

Amazon’s search engine A9 has recently unveiled a new service: yellow pages “like you’ve never seen before.”

“Using trucks equipped with digital cameras, global positioning system (GPS) receivers, and proprietary software and hardware, A9.com drove tens of thousands of miles capturing images and matching them with businesses and the way they look from the street.”

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

I can imagine online services like Mapquest getting into, or wanting to get into, this kind of image-banking. But I wouldn’t expect trucks with camera mounts to become a common sight on city streets. More likely, A9 is building up a first-run image bank to demonstrate what is possible. As people catch on, it would seem only natural that they would start accepting user contributions.  Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

A9’s new service does have a predecessor though, and it’s nearly 30 years old. In the late 70s, the Architecture Machine Group, which later morphed into the MIT Media Lab, developed some of the first prototypes of “interactive media.” Among them was the Aspen Movie Map, developed in 1978-79 by Andrew Lippman – a program that allowed the user to navigate the entirety of this small Colorado city, in whatever order they chose, in winter, spring, summer or fall, and even permitting them to enter many of the buildings. The Movie Map is generally viewed as the first truly interactive computer program. Now, with the explosion of digital photography, wireless networked devices, and image-caching across social networks, we might at last be nearing its realization on a grand scale.

hyperlinking the eye of the beholder

What if instead of just taking dorky pictures of your friends you could use your camera phone as an image swab, culling visual samples of the world around you and plugging them into a global database? Every transmitted picture would then be cross referenced with the global image bank and come back with information about what you just shot. A kind of “visual Google.”

What if instead of just taking dorky pictures of your friends you could use your camera phone as an image swab, culling visual samples of the world around you and plugging them into a global database? Every transmitted picture would then be cross referenced with the global image bank and come back with information about what you just shot. A kind of “visual Google.”

This may not be so far away. Take a look at this interview in TheFeature with computer vision researcher Hartmut Neven. Neven talks about “hyperlinking the world” through image-recognition software he has developed for handheld devices such as camera phones. If it were to actually expand to the scale Neven envisions (we’re talking billions of images), could it really work? Hard to say, but it’s quite a thought – sort of a global brain of Babel. Think of the brain as a library where information is accessed by sense (in this case vision) queries. Then make it earth-sized.

Here, in Neven’s words, is how it would work:

“You take a picture of something, send it to our servers, and we either provide you with more information or link you to the place that will. Let’s say you’re standing in front of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre. You take a snapshot with your cameraphone and instantly receive an audio-visual narrative about the painting. Then you step out of the Louvre and see a cafe. Should you go in? Take a shot from the other side of the street and a restaurant guide will appear on your phone. You sit down inside, but perhaps your French is a little rusty. You take a picture of the menu and a dictionary comes up to translate. There is a huge variety of people in these kinds of situations, from stamp collectors, to people who want to check their skin melanoma, to police officers who need to identify the person in front of them.”

But the technology has some very frightening implications as well, chief among them its potential for biometric human identification through “iris scanning and skin texture analysis.” This could have some fairly sensible uses, like an added security layer for banking and credit, but we’re dreaming if we think that will be the extent of it. Already, the Los Angeles Police Department is testing facial recognition programs based on Neven’s work – a library of “digital mugshots” that can be cross referenced with newly captured images from the street. Add this to a second Patriot Act and you’ve got a pretty nasty cocktail.

what’s a library?

In a recent discussion in these pages, Gary Frost has suggested that the Google library model would be premised on an inter-library loan system, “extending” the preeminence of print. Sure, enabling “inside the book” browsing of library collections will allow people to engage remotely with print volumes on distant shelves, and will help them track down physical copies if they so desire. But do we really expect this to be the primary function of such a powerful resource?

In a recent discussion in these pages, Gary Frost has suggested that the Google library model would be premised on an inter-library loan system, “extending” the preeminence of print. Sure, enabling “inside the book” browsing of library collections will allow people to engage remotely with print volumes on distant shelves, and will help them track down physical copies if they so desire. But do we really expect this to be the primary function of such a powerful resource?

We have to ask what this Google library intitiative is really aiming to do. What is the point? Is it simply a search tool for accessing physical collections, or is it truly a library in its own right? A library encompasses architecture, other people, temptations, distractions, whispers, touch. If the Google library is nothing more than a dynamic book locator, then it will have fallen terribly short of its immense potential to bring these afore-mentioned qualities into virtual space. Inside-the-book browsing is a sad echo of actual tactile browsing in a brick-and-mortar library. It’s a tease, or more likely, a sales hook. I think that’s far more likely to be the way people would use Google to track down print copies – consistent with Google’s current ad-based revenue structure.

But a library is not a retail space – it is an open door to knowledge, a highway with no tolls. How can we reinvent this in networked digital space?

more thoughts on salinas

Instead of becoming obsolete or extinct, local libraries should become portals to the global catalogue – a place where every conceivable text is directly obtainable. Instead of a library card, I might have a portable PC tablet that I use for all my e-texts, and I could plug into the stacks to download or search material. In this way, each library is every library.

But community libraries shouldn’t simply be a node on the larger network. They should cultivate their unique geographical and cultural situation and build themselves into repositories of local knowledge. By being freed, literally, of the weight of general print collections, local branches could really focus on cultivating rich, site-specific resources and multimedia archives of the surrounding environment.

In Salinas, for example, there are two bookshelves of Chicano literature at the Cesar Chavez Library – a precious, unique resource that will soon be inaccessible as libraries close to solve the city’s budget crisis. With all library collections digitized, you wouldn’t have to physically be in Salinas to access the Chicano shelves, but Salinas would remain the place where the major archival work is conducted, and where the storehouse of material artifacts is located.

In Salinas, for example, there are two bookshelves of Chicano literature at the Cesar Chavez Library – a precious, unique resource that will soon be inaccessible as libraries close to solve the city’s budget crisis. With all library collections digitized, you wouldn’t have to physically be in Salinas to access the Chicano shelves, but Salinas would remain the place where the major archival work is conducted, and where the storehouse of material artifacts is located.

It would be a shame for libraries to lose their local character, or for knowledge to become standardized because of big equalizers like Google. But when federal and municipal money is so tight that libraries are actually closing down, can we really expect the digitization of libraries to be achieved by anyone but the big commercial entities (like Google)? And if they’re the ones in charge, can we really count on getting the kind of access to books that libraries once provided? (image: Cesar Chavez Library, Salinas)

another ann arbor thought: borders and google

Ann Arbor is also the birthplace of Borders Books, a megabookstore similar to Barnes & Noble. It started in the 70s as a small used bookstore and evolved into a superstore which, according to their website, serves “some 30 million customers annually in over 1,200 stores.”

The Borders’ website credits their success to, “a revolutionary inventory system that tailored each store’s selection to the community it served.” In other words, they applied small bookstore strategy–get to know the particulars of a customer’s reading habits–on a larger scale. Since Google has chosen Ann Arbor as one locus of its nascent megalibrary, I got to thinking, what might these two distributors have in common (besides A2)? Google might be taking a cue from Borders when it designs the cyberlibrarian to accompany its digital collection. The small bookstore owner learns, through interaction, what a particular community wants. Borders’ inventory system tracked what the client was buying and selling. Google may, likewise, be able to track your buying and selling, your searching and asking. Perhaps the automaton Google librarian will “know” you based on information accumulated by all the various Google searches you have conducted. Problem is, that’s marketing strategy, not educational strategy. Will the Google librarian be able to make intuitive leaps leading the browser to things he/she is not familiar with rather than to more of what he/she already knows? How will search engines answer the need for this kind of expertise?

closing down salinas

The 150,000 citizens of Salinas, California will soon be without a single public library – a drastic measure taken by the city to solve a drastic budget crisis. After a pair of last-minute ballot measures failed to win funds for the city’s embattled libraries, the doors will soon close on what is for many curious minds, the only resource in town.

The 150,000 citizens of Salinas, California will soon be without a single public library – a drastic measure taken by the city to solve a drastic budget crisis. After a pair of last-minute ballot measures failed to win funds for the city’s embattled libraries, the doors will soon close on what is for many curious minds, the only resource in town.

Is the local community library going extinct? (image: John Steinbeck Library, Salinas)

after a holiday visit to ann arbor: the u of m library & google

I have fond memories of studying in the University of Michigan libraries, (as a high school student, and later as a U of M undergraduate). The physical space of the library, the seemingly endless stacks of books, which allowed deep exploration of even the most obscure topics, and gave me a sense of how vast, (and how limited) the universe of human thought really is. How is this going to be translated in the virtual space of Google’s digital library?

Isn’t it the job of the University library to provide a young scholar with opportunities to “see” the scope of human knowledge? While at the same time, offering a kind of temple space for the engagement of these books. Without the marble staircases, the chandeliers, the stone pilasters, the big oak tables, the reference room, the stained glass windows, the hushed silence, how will we get the message that books are important, and that understanding them requires a particular “space.” The physical space of the library serves as a metaphor and a reminder of the serious mental space that needs to be carved out for productive study. What will we lose when that space becomes “virtual?” Are we “saving” space by putting everything in the computer? Or are we losing it?

google takes on u. of michigan library – the numbers

– 7,000,000: Volumes in the U-M library to be digitized.

– 2,380,000,000: Estimated number of pages.

– 743,750,000,000: Estimated number of words.

– 1,600: Years it would take U-M to digitize all 7 million volumes without Google’s special technology.

– Fewer than 7: Years it will take to digitize the volumes with Google’s technology.

– $1 billion: Estimated value of the project to U-M.

Source: John Wilkin, associate university librarian, library information technology and technical and access services, University of Michigan

U-M’s entire library to be put on Google – Detroit Free Press