Open Source’s hour on the Googlization of libraries was refreshingly light on the copyright issue and heavier on questions about research, reading, the value of libraries, and the public interest. With its book-scanning project, Google is a private company taking on the responsibilities of a public utility, and Siva Vaidhyanathan came down hard on one of the company’s chief legal reps for the mystery shrouding their operations (scanning technology, algorithms and ranking system are all kept secret). The rep reasonably replied that Google is not the only digitization project in town and that none of its library partnerships are exclusive. But most of his points were pretty obvious PR boilerplate about Google’s altruism and gosh darn love of books. Hearing the counsel’s slick defense, your gut tells you it’s right to be suspicious of Google and to keep demanding more transparency, clearer privacy standards and so on. If we’re going to let this much information come into the hands of one corporation, we need to be very active watchdogs.

Our friend Karen Schneider then joined the fray and as usual brought her sage librarian’s perspective. She’s thrilled by the possibilities of Google Book Search, seeing as it solves the fundamental problem of library science: that you can only search the metadata, not the texts themselves. But her enthusiasm is tempered by concerns about privatization similar to Siva’s and a conviction that a research service like Google can never replace good librarianship and good physical libraries. She also took issue with the fact that Book Search doesn’t link to other library-related search services like Open Worldcat. She has her own wrap-up of the show on her blog.

Rounding out the discussion was Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, a cybertext studies blogger and professor of english at the University of Maryland. Kirschenbaum addressed the question of how Google, and the web in general, might be changing, possibly eroding, our reading practices. He nicely put the question in perspective, suggesting that scattershot, inter-textual, “snippety” reading is in fact the older kind of reading, and that the idea of sustained, deeply immersed involvement with a single text is largely a romantic notion tied to the rise of the novel in the 18th century.

A satisfying hour, all in all, of the sort we should be having more often. It was fun brainstorming with Brendan Greeley, the Open Source on “blogger-in-chief,” on how to put the show together. Their whole bit about reaching out to the blogosphere for ideas and inspiration isn’t just talk. They put their money where their mouth is. I’ll link to the podcast when it becomes available.

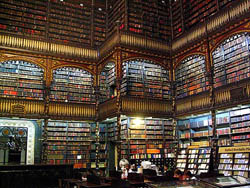

image: Real Gabinete Português de Literatura, Rio de Janeiro – Claudio Lara via Flickr

Category Archives: Libraries, Search and the Web

thinking about google books: tonight at 7 on radio open source

While visiting the Experimental Television Center in upstate New York this past weekend, Lisa found a wonderful relic in a used book shop in Owego, NY — a small, leatherbound volume from 1962 entitled “Computers,” which IBM used to give out as a complimentary item. An introductory note on the opening page reads:

The machines do not think — but they are one of the greatest aids to the men who do think ever invented! Calculations which would take men thousands of hours — sometimes thousands of years — to perform can be handled in moments, freeing scientists, technicians, engineers, businessmen, and strategists to think about using the results.

This echoes Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 essay on computing and networked knowledge, “As We May Think”, which more or less prefigured the internet, web search, and now, the migration of print libraries to the world wide web. Google Book Search opens up fantastic possibilities for research and accessibility, enabling readers to find in seconds what before might have taken them hours, days or weeks. Yet it also promises to transform the very way we conceive of books and libraries, shaking the foundations of major institutions. Will making books searchable online give us more time to think about the results of our research, or will it change the entire way we think? By putting whole books online do we begin the steady process of disintegrating the idea of the book as a bounded whole and not just a sequence of text in a massive database?

The debate thus far has focused too much on the legal ramifications — helped in part by a couple of high-profile lawsuits from authors and publishers — failing to take into consideration the larger cognitive, cultural and institutional questions. Those questions will hopefully be given ample air time tonight on Radio Open Source.

Tune in at 7pm ET on local public radio or stream live over the web. The show will also be available later in the week as a podcast.

the role of note taking in the information age

An article by Ann Blair in a recent issue of Critical Inquiry (vol 31 no 1) discusses the changing conceptions of the function of note-taking from about the sixth century to the present, and ends with a speculation on the way that textual searches (such as Google Book Search) might change practices of note-taking in the twenty-first century. Blair argues that “one of the most significant shifts in the history of note taking” occured in the beginning of the twentieth century, when the use of notes as memorization aids gave way to the use of notes as a aid to replace the memorization of too-abundant information. With the advent of the net, she notes:

Today we delegate to sources that we consider authoritative the extraction of information on all but a few carefully specialized areas in which we cultivate direct experience and original research. New technologies increasingly enable us to delegate more tasks of remembering to the computer, in that shifting division of labor between human and thing. We have thus mechanized many research tasks. It is possible that further changes would affect even the existence of note taking. At a theoretical extreme, for example, if every text one wanted were constantly available for searching anew, perhaps the note itself, the selection made for later reuse, might play a less prominent role.

The result of this externalization, Blair notes, is that we come to think of long-term memory as something that is stored elsewhere, in “media outside the mind.” At the same time, she writes, “notes must be rememorated or absorbed in the short-term memory at least enough to be intelligently integrated into an argument; judgment can only be applied to experiences that are present to the mind.”

Blair’s article doesn’t say that this bifurcation between short-term and long-term memory is a problem: she simply observes it as a phenomenon. But there’s a resonance between Blair’s article and Naomi Baron’s recent Los Angeles Times piece on Google Book Search: both point to the fact that what we commonly have defined as scholarly reflection has increasingly become more and more a process of database management. Baron seems to see reflection and database management as being in tension, though I’m not completely convinced by her argument. Blair, less apocalyptic than Baron, nonetheless gives me something to ponder. What happens to us if (or when) all of our efforts to make the contents of our extrasomatic memory “present to our mind” happen without the mediation of notes? Blair’s piece focuses on the epistemology rather than the phenomenology of note taking — still, she leads me to wonder what happens if the mediating function of the note is lost, when the triangular relation between book, scholar and note becomes a relation between database and user.

killing the written word?

A November 28 Los Angeles Times editorial by American University linguistics professor Naomi Barron adds another element to the debate over Google Print [now called Google Book Search, though Baron does not use this name]: Baron claims that her students are already clamoring for the abridged, extracted texts and have begun to feel that book-reading is passe. She writes:

Much as automobiles discourage walking, with undeniable consequences for our health and girth, textual snippets-on-demand threaten our need for the larger works from which they are extracted… In an attempt to coax students to search inside real books rather than relying exclusively on the Web for sources, many professors require references to printed works alongside URLs. Now that those “real” full-length publications are increasingly available and searchable online, the distinction between tangible and virtual is evaporating…. Although [the debate over Google Print] is important for the law and the economy, it masks a challenge that some of us find even more troubling: Will effortless random access erode our collective respect for writing as a logical, linear process? Such respect matters because it undergirds modern education, which is premised on thought, evidence and analysis rather than memorization and dogma. Reading successive pages and chapters teaches us how to follow a sustained line of reasoning.

As someone who’s struggled to get students to go to the library while writing their papers, I think Baron’s making a very important and immediate pedagogical point: what will professors do after Google Book Search allows their students to access bits of “real books” online? Will we simply establish a policy of not allowing the online excerpted material to “count” in our tally of student’s assorted research materials?

On the other hand, I can see the benefits of having a student use Google Book Search in their attempt to compile an annotated bibliography for a research project, as long as they were then required to look at a version of the longer text (whether on or off-line). I’m not positive that “random effortless access” needs to be diametrically opposed to instilling the practice of sustained reading. Instead, I think we’ve got a major educational challenge on our hands whose exact dimensions won’t be clear until Google Book Search finally gets going.

Also: thanks to UVM English Professor Richard Parent for posting this article on his blog, which has some interesting ruminations on the future of the book.

katrina archive on internet archive

The Internet Archive has just established an archive dedicated to preserving the online response to the Katrina catastrophe. According to the Archive:

The Internet Archive and many individual contributors worked together to put together a comprehensive list of websites to create a historical record of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina and the massive relief effort which followed. This collection has over 25 million unique pages, all text searchable, from over 1500 sites. The web archive commenced on September 4th.

If you try to link to the Internet Archive today, you might not get through, because everyone is on the site talking about the Grateful Dead’s decision to allow free downloading

google print on deck at radio open source

Open Source, the excellent public radio program (not to be confused with “Open Source Media”) that taps into the blogosphere to generate its shows, has been chatting with me about putting together an hour on the Google library project. Open Source is a unique hybrid, drawing on the best qualities of the blogosphere — community, transparency, collective wisdom — to produce an otherwise traditional program of smart talk radio. As host Christopher Lydon puts it, the show is “fused at the brain stem with the world wide web.” Or better, it “uses the internet to be a show about the world.”

The Google show is set to air live this evening at 7pm (ET) (they also podcast). It’s been fun working with them behind the scenes, trying to figure out the right guests and questions for the ideal discussion on Google and its bookish ambitions. My exchange has been with Brendan Greeley, the Radio Open Source “blogger-in-chief” (he’s kindly linked to us today on their site). We agreed that the show should avoid getting mired in the usual copyright-focused news peg — publishers vs. Google etc. — and focus instead on the bigger questions. At my suggestion, they’ve invited Siva Vaidhyanathan, who wrote the wonderful piece in the Chronicle of Higher Ed. that I talked about yesterday (see bigger questions). I’ve also recommended our favorite blogger-librarian, Karen Schneider (who has appeared on the show before), science historian George Dyson, who recently wrote a fascinating essay on Google and artificial intelligence, and a bunch of cybertext studies people: Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, N. Katherine Hayles, Jerome McGann and Johanna Drucker. If all goes well, this could end up being a very interesting hour of discussion. Stay tuned.

UPDATE: Open Source just got a hold of Nicholas Kristof to do an hour this evening on Genocide in Sudan, so the Google piece will be pushed to next week.

sober thoughts on google: privatization and privacy

Siva Vaidhyanathan has written an excellent essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education on the “risky gamble” of Google’s book-scanning project — some of the most measured, carefully considered comments I’ve yet seen on the issue. His concerns are not so much for the authors and publishers that have filed suit (on the contrary, he believes they are likely to benefit from Google’s service), but for the general public and the future of libraries. Outsourcing to a private company the vital task of digitizing collections may prove to have been a grave mistake on the part of Google’s partner libraries. Siva:

The long-term risk of privatization is simple: Companies change and fail. Libraries and universities last…..Libraries should not be relinquishing their core duties to private corporations for the sake of expediency. Whichever side wins in court, we as a culture have lost sight of the ways that human beings, archives, indexes, and institutions interact to generate, preserve, revise, and distribute knowledge. We have become obsessed with seeing everything in the universe as “information” to be linked and ranked. We have focused on quantity and convenience at the expense of the richness and serendipity of the full library experience. We are making a tremendous mistake.

This essay contains in abundance what has largely been missing from the Google books debate: intellectual courage. Vaidhyanathan, an intellectual property scholar and “avowed open-source, open-access advocate,” easily could have gone the predictable route of scolding the copyright conservatives and spreading the Google gospel. But he manages to see the big picture beyond the intellectual property concerns. This is not just about economics, it’s about knowledge and the public interest.

What irks me about the usual debate is that it forces you into a position of either resisting Google or being its apologist. But this fails to get at the real bind we all are in: the fact that Google provides invaluable services and yet is amassing too much power; that a private company is creating a monopoly on public information services. Sooner or later, there is bound to be a conflict of interest. That is where we, the Google-addicted public, are caught. It’s more complicated than hip versus square, or good versus evil.

Here’s another good piece on Google. On Monday, The New York Times ran an editorial by Adam Cohen that nicely lays out the privacy concerns:

Google says it needs the data it keeps to improve its technology, but it is doubtful it needs so much personally identifiable information. Of course, this sort of data is enormously valuable for marketing. The whole idea of “Don’t be evil,” though, is resisting lucrative business opportunities when they are wrong. Google should develop an overarching privacy theory that is as bold as its mission to make the world’s information accessible – one that can become a model for the online world. Google is not necessarily worse than other Internet companies when it comes to privacy. But it should be doing better.

Two graduate students in Stanford in the mid-90s recognized that search engines would the most important tools for dealing with the incredible flood of information that was then beginning to swell, so they started indexing web pages and working on algorithms. But as the company has grown, Google’s admirable-sounding mission statement — “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” — has become its manifest destiny, and “information” can now encompass the most private of territories.

At one point it simply meant search results — the answers to our questions. But now it’s the questions as well. Google is keeping a meticulous record of our clickstreams, piecing together an enormous database of queries, refining its search algorithms and, some say, even building a massive artificial brain (more on that later). What else might they do with all this personal information? To date, all of Google’s services are free, but there may be a hidden cost.

“Don’t be evil” may be the company motto, but with its IPO earlier this year, Google adopted a new ideology: they are now a public corporation. If web advertising (their sole source of revenue) levels off, then investors currently high on $400+ shares will start clamoring for Google to maintain profits. “Don’t be evil to us!” they will cry. And what will Google do then?

images: New York Public Library reading room by Kalloosh via Flickr; archive of the original Google page

virtual libraries, real ones, empires

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

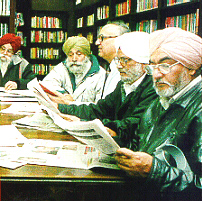

Libraries are inherently islands of freedom and antidotes to fanaticism. They are temples of pluralism where books that contradict one another stand peacefully side by side just as intellectual antagonists work peacefully next to each other in reading rooms. It is legitimate and in our nation’s interest that the new technology be used internationally, both by the private sector to promote economic enterprise and by the public sector to promote democratic institutions. But it is also necessary that America have a more inclusive foreign cultural policy — and not just to blunt charges that we are insensitive cultural imperialists. We have an opportunity and an obligation to form a private-public partnership to use this new technology to celebrate the cultural variety of the world.

What’s interesting about this quote (among other things) is that Billington seems to be suggesting that a World Digital Library would function in much the same manner as a real-world library, and yet he’s also arguing for the importance of actual physical proximity. He writes, after all, about books literally, not virtually, touching each other, and about researchers meeting up in a shared reading room. There seems to be a tension here, in other words, between Billington’s embrace of the idea of a world digital library, and a real anxiety about what a “library” becomes when it goes online.

I also feel like there’s some tension here — in Billington’s editorial and in the whole World Digital Library project — between “inclusiveness” and “imperialism.” Granted, if the United States provides Brazilians access to their own national literature online, this might be used by some as an argument against the idea that we are “insensitive cultural imperialists.” But there are many varieties of empire: indeed, as many have noted, the sun stopped setting on Google’s empire a while ago.

To be clear, I’m not attacking the idea of the World Digital Library. Having watch the Smithsonian invest in, and waffle on, some of their digital projects, I’m all for a sustained commitment to putting more material online. But there needs to be some careful consideration of the differences between online libraries and virtual ones — as well as a bit more discussion of just what a privately-funded digital library might eventually morph into.

explosion

![]() A Nov. 18 post on Adam Green’s Darwinian Web makes the claim that the web will “explode” (does he mean implode?) over the next year. According to Green, RSS feeds will render many websites obsolete:

A Nov. 18 post on Adam Green’s Darwinian Web makes the claim that the web will “explode” (does he mean implode?) over the next year. According to Green, RSS feeds will render many websites obsolete:

The explosion I am talking about is the shifting of a website’s content from internal to external. Instead of a website being a “place” where data “is” and other sites “point” to, a website will be a source of data that is in many external databases, including Google. Why “go” to a website when all of its content has already been absorbed and remixed into the collective datastream.

Does anyone agree with Green? Will feeds bring about the restructuring of “the way content is distributed, valued and consumed?” More on this here.

world digital library

The Library of Congress has announced plans for the creation of a World Digital Library, “a shared global undertaking” that will make a major chunk of its collection freely available online, along with contributions from other national libraries around the world. From The Washington Post:

The Library of Congress has announced plans for the creation of a World Digital Library, “a shared global undertaking” that will make a major chunk of its collection freely available online, along with contributions from other national libraries around the world. From The Washington Post:

…[the] goal is to bring together materials from the United States and Europe with precious items from Islamic nations stretching from Indonesia through Central and West Africa, as well as important materials from collections in East and South Asia.

Google has stepped forward as the first corporate donor, pledging $3 million to help get operations underway. At this point, there doesn’t appear to be any direct connection to Google’s Book Search program, though Google has been working with LOC to test and refine its book-scanning technology.