The Times has published its first video “letter to the editor,” a 10-minute mini-documentary by Charles Ferguson on the decision by L. Paul Bremer and other US officials to disband the Iraqi army shortly after the US occupation began. The video is posted as a rebuttal to a recent op-ed by Bremer that tried to redistribute some of the blame for that catastrophic blunder that arguably gave birth to the Sunni insurgency.

This is no doubt a milestone for the paper, although calling it a letter to the editor is slightly disingenuous. Ferguson isn’t just your average concerned reader, he’s a highly respected filmmaker and author who has made a full length doc about Iraq, “No End in Sight,” from which much of this video’s material is taken.

Moreover, at ten minutes, and meticulously edited and produced, filled with interviews with top military brass and gov’t officials, the clip is more on par (at the very least) with a full op-ed. The main opinion page even features it as such – ?under op-ed contributors – ?rather than placing it down among the letters. Will we eventually see actual ad hoc video letters to the editor from “readers” at large? That could be interesting.

Nomenclature aside, though, this is a fantastic broadening of the Times‘ editorial output. Once again, they prove themselves to be one of the more innovative digital publishers around.

Category Archives: iraq

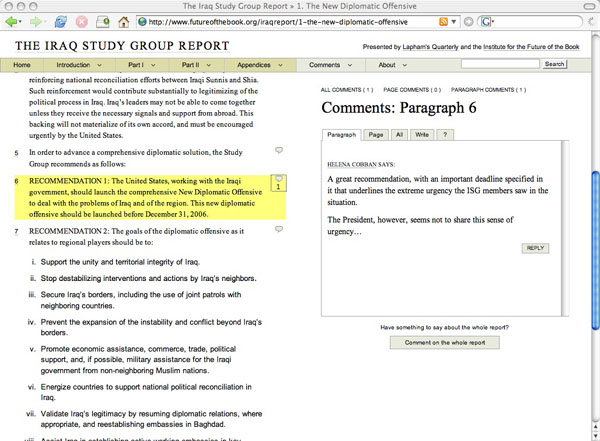

bush’s iraq speech: a critical edition

Last month we published an online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report in a new format we’re developing (in-house name is “Comment Press”) that allows readers to enter into conversation with a text and with one another. This was a first step in a creative partnership with Lewis Lapham and Lapham’s Quarterly, a new journal that will look at contemporary issues through the lens of history. Launching only a few days before Christmas, the timing was certainly against us. Only a handful of commenters showed up in those first few days, slowing down almost to a halt as the holiday hibernation period set in. Since New Year’s, however, the site has been picking up momentum and has now amassed a sizable batch of commentary on the Report from a diverse group of respondents including Howard Zinn, Frances FitzGerald and Gary Hart.

While that discussion continues to develop in the Report’s margins, we are following it up with a companion text: the transcript and video of President Bush’s address to the nation last night where he outlined his new strategy for Iraq, presented in a similarly Talmudic fashion with commentary accreting around the central text. To these two documents invited readers and other interested members of the public can continue to append their comments, criticisms and clarifications, “at liberty to find,” in Lapham’s words, “‘the way forward’ in or out of Iraq, back to the future or across the Potomac and into the trees.”

An added feature this time around is that we’re opening the door to general commenters, although with a fairly high barrier to entry. This is an experiment with a more rigorously moderated kind of web discussion and a chance for Lapham and his staff to begin to explore what it means to be editors in the network environment. Anyone is welcome to apply for entry into the discussion by providing a little background on themselves and a sample first comment. If approved by the Lapham’s Quarterly editors (this will all happen within the same day), they will be given a login, at which point they can fire at will on both the speech and the report.

Together these two publications comprise Operation Iraqi Quagmire, a journalistic experiment and a gesture toward a new way of handling public documents in a networked democracy.

***Note: we strongly recommend viewing this on Firefox***

live, on the web, it’s the iraq study group report!

Since leaving Harper’s last spring, Lewis Lapham has been developing plans for a new journal, Lapham’s Quarterly, which will look at important contemporary subjects (one per issue) through the lens of history. Not long ago, Lewis approached the Institute about helping him and his colleagues to develop a web component of the Quarterly, which he imagined as a kind of unorthodox news site where history and source documents would serve as a decoder ring for current events — a trading post of ideas, facts, and historical parallels where readers would play a significant role in piecing together the big picture. To begin probing some of the possibilities for this collaboration, we came up with an exciting and timely experiment: we’ve taken the granular commenting format that we hacked together just a few weeks ago for Mitch Stephens’ paper and plugged in the Iraq Study Group Report. The Lapham crew, for their part, have taken their first editorial plunge into the web, using their broad print network to assemble an astonishing roster of intellectual heavyweights to collectively annotate the text, paragraph by paragraph, live on the site. Here’s more from Lewis:

As expected and in line with standard government practice, the report issued by the Iraq Study Group on December 6th comes to us written in a language that guards against the crime of meaning–a document meant to be admired as a praise-worthy gesture rather than understood as a clear statement of purpose or an intelligible rendition of the facts. How then to read the message in the bottle or the handwriting on the wall?

Lapham’s Quarterly and the Institute for the Future of the Book answers the question with a new form of discussion and critique– an annotated edition of the ISG Report on a website programmed to that specific purpose, evolving over the course of the next three weeks into a collaborative illumination of an otherwise black hole. What you have before you is the humble beginnings of that effort–the first few marginal notes and commentaries furnished by what will eventually be a large number of informed sources both foreign and domestic (historians, military officers, politicians, intelligence operatives, diplomats, some journalists), invited to amend, correct, augment or contradict any point in the text seemingly in need of further clarification or forthright translation into plain English.

As the discussion adds to the number of its participants so also it will extend the reach of its memory and enlarge its spheres of reference. What we hope will take shape on short notice and in real time is the publication of a report that should prove to be a good deal more instructive than the one distributed to the members of Congress and the major news media.

Being at the very beginning of the experiment, what you’ll see on the site today is more or less a blank slate. Our hope is that in the days and weeks ahead, a lively conversation will begin to bubble up in the pages of the report — a kind of collaborative marginalia on a grand scale — mounting toward Bush’s big Iraq strategy speech next month. Around that time, the Lapham’s editors will open up commenting to the public. Until then, here are just some of the people we expect to participate: Anthony Arnove, Helena Cobban, Joshua Cohen, Jean Daniel, Raghida Dergham, Joan Didion, Mark Danner, Barbara Ehrenrich, Daniel Ellsberg, Tom Engelhardt, Stanley Fish, Robert Fisk, Eric Foner, Christopher Hitchens, Rashid Khalidi, Chalmers Johnson, Donald Kagan, Kanan Makiya, William Polk, Walter Russel Mead, Karl Meyer, Ralph Nader, Gianni Riotta, M.J. Rosenberg, Gary Sick, Matthew Stevenson, Frances Stonor, Lally Weymouth, and Wayne White.

Not too shabby.

The form is still very much in the R&D phase, but we’ve made significant improvements since the last round. Add this to your holiday reading stack and watch how it develops.

(We strongly recommend viewing the site in Firefox.)

2 – dimensions just aren’t enough

We’re burning way too much midnight oil this weekend trying to ready a networked version of the Iraq Study Group report for release next week. We’ll introduce the project itself in a few days, but right now i just want to mention that i think we’re about at the end of our ability to organize these very complex reading/writing projects using the 2-dimensional design constraints inherited from print. Ben came to the same conclusion in his recent post inspired by the difficulty of designing the site for Mitch Stephens’ paper, Holy of Holies. My first resolution for 2007 is to try an experiments building a networked book inside of Second Life or some other three-dimensional environment.

how would you design the iraq study group report for the web?

The “Iraq Study Group Report” paperback could have been wrapped in a brown paper bag, its title scrawled in Magic Marker. It would still sell. This is a book, unlike trillions of others on the market, whose substance and national import sell it, not its cover…Disproving the adage, this genre of book can indeed be judged by its cover. From the reports on the Warren Commission to Watergate, Iran-contra and now the Iraq war, such books are anomalies for a publishing industry that churns out covers intended to seduce readers, to reach out and grab them, and propel them to the cash register.

How would you design an unauthorized web edition of the ISG Report? Would you keep to the sober, no-nonsense aesthetic of the iconic print editions of past government documents like the 9/11 Commission Report or the Warren Commission Report? Or would you shake things up? A far more interesting question: what functionality would you add? What kind of discussion capabilities would you build into it? Who would you most like to see annotate or publicly comment on the document?

The electronic edition that has been making the rounds is an austere PDF made available by the United States Institute of Peace. A far more useful resource for close reading of the text was put out by Vivismo as a demonstration of its new Velocity Search Engine. They crawled the PDF and broke it into individual paragraphs, adding powerful clustered search tools.

The US Government Printing Office has a slew of public documents available on its website, mostly as PDFs or bare-bones HTML pages. How should texts of “national import” be reconceived for the network?

“a duopoly of Reuters-AP”: illusions of diversity in online news

Newswatch reports a powerful new study by the University of Ulster Centre for Media Research that confirms what many of us have long suspected about online news sources:

Through an examination of the content of major web news providers, our study confirms what many web surfers will already know – that when looking for reporting of international affairs online, we see the same few stories over and over again. We are being offered an illusion of information diversity and an apparently endless range of perspectives which in fact what is actually being offered is very limited information.

The appearance of diversity can be a powerful thing. Back in March, 2004, the McClatchy Washington Bureau (then Knight Ridder) put out a devastating piece revealing how the Iraqi National Congress (Ahmad Chalabi’s group) had fed dubious intelligence on Iraq’s WMDs not only to the Bush administration (as we all know), but to dozens of news agencies. The effect was a swarm of seemingly independent yet mutually corroborating reportage, edging American public opinion toward war.

A June 26, 2002, letter from the Iraqi National Congress to the Senate Appropriations Committee listed 108 articles based on information provided by the INC’s Information Collection Program, a U.S.-funded effort to collect intelligence in Iraq.

The assertions in the articles reinforced President Bush’s claims that Saddam Hussein should be ousted because he was in league with Osama bin Laden, was developing nuclear weapons and was hiding biological and chemical weapons.

Feeding the information to the news media, as well as to selected administration officials and members of Congress, helped foster an impression that there were multiple sources of intelligence on Iraq’s illicit weapons programs and links to bin Laden.

In fact, many of the allegations came from the same half-dozen defectors, weren’t confirmed by other intelligence and were hotly disputed by intelligence professionals at the CIA, the Defense Department and the State Department.

Nevertheless, U.S. officials and others who supported a pre-emptive invasion quoted the allegations in statements and interviews without running afoul of restrictions on classified information or doubts about the defectors’ reliability.

Other Iraqi groups made similar allegations about Iraq’s links to terrorism and hidden weapons that also found their way into official administration statements and into news reports, including several by Knight Ridder.

The repackaging of information goes into overdrive with the internet, and everyone, from the lone blogger to the mega news conglomerate, plays a part. Moreover, it’s in the interest of the aggregators and portals like Google and MSN to emphasize cosmetic or brand differences, so as to bolster their claims as indispensible filters for a tidal wave of news. So whether it’s Bush-Cheney-Chalabi’s WMDs or Google News’s “4,500 news sources updated continuously,” we need to maintain a skeptical eye.

***Related: myths of diversity in book publishing and large-scale digitization efforts.

a bone-chilling message to academics who dare to become PUBLIC intellectuals

Juan Cole is a distinguished professor of middle eastern studies at the University of Michigan. Juan Cole is also the author of the extremely influential blog, Informed Comment which tens of thousands of people rely on for up-to-the-minute news and analysis of what is happening in Iraq and in the middle east more generally. It was recently announced that Yale University rejected Cole’s nomination for a professorship in middle eastern studies, even after he had been approved by both the history and sociology departments. As might be expected there is considerable outcry, particularly from the progressive press and blogosphere criticizing Yale for caving in to what seems to have been a well-orchestrated campaign against Cole by the hard-line pro-Israel forces in the U.S.

Most of the stuff I’ve read so far seems to concentrate on taking Yale’s administration to task for their spinelessness. While this criticism seems well-founded, I think there is a bigger issue that isn’t being addressed. The conservatives didn’t go after Cole simply because of his political ideas. There are most likely people already in Yale’s Middle Eastern studies dept. with politics more radical than Cole’s. They went after him because his blog, which reaches out to a broad general audience is read by tens of thousands and ensures that his ideas have a force in the world. Juan once told me that he’s lucky if he sells 500 copies of his scholarly books. His blog however ranks in the Technorati 50 and through his blog he has also picked up influential gigs in Salon and NPR.

Yale’s action will have a bone-chilling effect on academic bloggers. Before the Cole/Yale affair it was only non-tenured professors who feared that speaking out publicly in blogs might have a negative impact on their careers. Now with Yale’s refusal to approve the recommendation of its academic departments — even those with tenure must realize that if they dare to go outside the bounds of the academy to take up the responsibilities of public intellectuals, that the path to career advancement may be severely threatened.

We should have defended Juan Cole more vigorously, right from the beginning of the right-wing smear against him. Let’s remember that the next time a progressive academic blogger gets tarred by those who are afraid of her ideas.

war machinima

Ray, Bob and I spent last week out in Los Angeles at our institutional digs (the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC), where we held a pair of meetings with professors from around the US and Canada to discuss various coups we are attempting to stage within the ossified realm of scholarly and textbook publishing. Following these, we were able to stick around for a fun conference/media festival organized by Annenberg’s Networked Publics project.

The conference was a mix of the usual academic panels and a series of curated mini-exhibits of “do-it-yourself” media, surveying new genres of digital folk art currently proliferating across the net such as political remix movies, anime music videos, “digital handmade” art projects (which featured the near and dear Alex Itin — happy birthday, Alex!), and of course, machinima: films made inside of video game engines.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

Back in 2004, director Deborah Scranton gave video cameras to ten members of the New Hampshire National Guard who were about to depart for a yearlong tour in Iraq. They went on to shoot a combined 800 hours of film, the pared-down result of which is “The War Tapes.” Reading about it, I couldn’t help but think that here was a case of real-life machinima. Give the warriors cameras and glimpse the war machine from the inside — carve out a new game within the game.

Granted, it’s a far from perfect analogy. Machinima involves a total repurposing of the characters and environment, foregoing the intended objectives of the game. In “The War Tapes,” the soldiers are still on their mission, still within the chain of command. And of course, war isn’t a video game. But isn’t it advertised as one?

Time Square, New York City (the military-entertainment complex)

There’s something undeniably subversive about giving cameras to GIs in what is such a thoroughly mediated war, a sort of playing against the game — if not of the game of occupation as a whole, then at least the game of spin. “I’m not supposed to talk to the media,” says one soldier to Steve Pink, one of the film’s main subjects, as he attempts to conduct an interview. To which Pink replies: “I’m not the media, dammit!”

In the clips I found on the film’s promotional site (the general release is later this summer), the overriding impression is of the soldiers’ isolation and fear: the constant terror of roadside bombs, frantic rounds fired into the green night-vision darkness, swaddled in helmets and humvees and hi-tech weaponry. It’s a frightening game they play. Deeply impersonal and anonymous, and in no way resembling the pumped-up, guitar-screeching game that the military portrays as war in its recruiting ads. This is the horrible truth at the bottom of the “Army of One” slogan: you are a lone digit in a massive calculation. Just pray you don’t become a zero.

Yet naturally, they find their own games to play within the game. One clip shows the tiny, gruesome spectacle of two soldiers, in a moment of leisure, pitting a scorpion against a spider inside a plastic tub, reenacting their own plight in the language of the desert.

At the Net Publics conference, we did see see one example of genuine machinima that made its own spooky commentary on the war: a hack of Battlefield 2 by Swedish game forum Snoken that brilliantly apes the now-famous Sony Bravia commercial, in which 250,000 colored plastic balls were filmed cascading through the streets of a San Francisco.

Here’s Battlefield:

And here’s the original Sony ad:

McKenzie Wark doesn’t address machinima in GAM3R 7H30RY (which launches in about a week), but he does discuss video games in the context of the “military entertainment complex”: the remaking of postmodern capitalist society in the image of the digital game, in which every individual is a 1 or a 0 locked in senseless competition for advancement through the levels, each vying to “win” the game:

The old class antagonisms have not gone away, but are hidden beneath levels of rank, where each agonizes over their worth against others in the price of their house, the size of their vehicle and where, perversely, working longer and longer hours is a sign of winning the game. Work becomes play. Work demands not just one’s mind and body but also one’s soul. You have to be a team player. Your work has to be creative, inventive, playful – ludic, but not ludicrous.

Video games (which can actually be won) are allegories of this imperfect world that we are taught to play like a game, as though it really were governed by a perfect (and perfectly fair) algorithm — even the wars that rage across its hemispheres:

Once games required an actual place to play them, whether on the chess board or the tennis court. Even wars had battle fields. Now global positioning satellites grid the whole earth and put all of space and time in play. Warfare, they say, now looks like video games. Well don’t kid yourself. War is a video game – for the military entertainment complex. To them it doesn’t matter what happens ‘on the ground’. The ground – the old-fashioned battlefield itself – is just a necessary externality to the game. Slavoj Zizek: “It is thus not the fantasy of a purely aseptic war run as a video game behind computer screens that protects us from the reality of the face to face killing of another person; on the contrary it is this fantasy of face to face encounter with an enemy killed bloodily that we construct in order to escape the Real of the depersonalized war turned into an anonymous technological operation.” The soldier whose inadequate armor failed him, shot dead in an alley by a sniper, has his death, like his life, managed by a computer in a blip of logistics.

How does one truly escape? Ultimately, Wark’s gamer theory is posed in the spirit that animates the best machinima:

The gamer as theorist has to choose between two strategies for playing against gamespace. One is to play for the real. (Take the red pill). But the real is nothing but a heap of broken images. The other is to play for the game (Take the blue pill). Play within the game, but against gamespace. Be ludic, but also lucid.

milblogs on veteran’s day

Thought it would be appropriate today to talk about what’s going on with military blogging. Last August, John Hockenberry explored the world of war blogging (or milblogging) at length in a Wired article, The Blogs of War. Hockenberry noted that war bloggers are not just recording events — rather, “they engage in the 21st-century contact sport called punditry, and like their civilian counterparts, follow few rules of engagement. They mobilize sympathizers to ship body armor to reserve units in combat, raise funds for families of wounded soldiers, deliver shoes to barefoot Afghani kids, and even take aim at media big shots.” He also drew a connection between the influence and prominence of milblogs and the few restrictions imposed on them by the military: what’s radical about milblogs is that “anyone can publicly post a dispatch, and if the Pentagon reads these accounts at all, it’s at the same time as the rest of us.” Still, Hockenberry added, even the bloggers themselves were feeling like the freedom they enjoyed wouldn’t last.

How right he was. Only a week after the article ran, the Army issued a memo to all personnel saying they were going to crack down on the milbloggers. It’s probably not a stretch to imagine that the Wired piece and a similar article in the Washington Post caught the eye of someone in the Public Relations office. According to an NPR story on the topic, some soldiers felt like the crackdown had a less to do with security than with the fact that some military bloggers were becoming increasingly sour about the war. Since the new regulations were released in October, several influential milblogs have been “vanished” from the web by the Army. One notable recent example is Daniel Goetz’s All The King’s Horses, a eloquently written blog by a patriotic but disenchanted soldier in Iraq. Goetz’s final post, on October 22, was a creepily Orwellian retraction (literally, since he titled it Double Plus Ungood) of what he’d been blogging in his final weeks:

“For the record, I am officially a supporter of the administration and of her policies. I am a proponent for the war against terror and I believe in the mission in Iraq…Furthermore, I have the utmost confidence in the leadership of my chain of command, including (but not limited to) the president George Bush and the honorable secretary of defense Rumsfeld. If I have ever written anything on this site or on others that lead the reader to believe otherwise, please consider this a full and complete retraction. I apologize for any misunderstandings that might understandably arise from this. Should you continue to have questions, please feel free to contact me through e-mail. I promise to respond personally to each, but it may take some time; my internet access has become restricted.”

There’s been a great deal of discussion of David’s fate in the blogosphere. Daniel’s girlfriend, who has been blogging herself in Daniel’s absence, posted his entired deleted blog on her own site.

the huffington post… we’re intrigued

A week after the May 9 debut of The Huffington Post, Nikki Finke delivered this bitter assessment in LA Weekly:

Judging from Monday’s horrific debut of the humongously pre-hyped celebrity blog the Huffington Post, the Madonna of the mediapolitic world has undergone one reinvention too many. She has now made an online ass of herself. What her bizarre guru-cult association, 180-degree right-to-left conversion, and failed run in the California gubernatorial-recall race couldn’t accomplish, her blog has now done: She is finally played out publicly. This website venture is the sort of failure that is simply unsurvivable. Her blog is such a bomb that it’s the movie equivalent of Gigli, Ishtar and Heaven’s Gate rolled into one. In magazine terms, it’s the disastrous clone of Tina Brown’s Talk, JFK Jr.’s George or Maer Roshan’s Radar.

Finke was not alone in her prediction of disaster. And at the time, it wasn’t so unreasonable to suspect Arianna Huffington’s experiment with celebrity group blogging might crash and burn spectacularly (The Guardian ran a very funny satire in anticipation). But by now it’s clear that not only are reports of Huffington’s death greatly exaggerated, but that something of value has been created.

The site is getting a load of traffic (a million and a half a month as of September, probably significantly more by now). As expected, it is snarky, eclectic and irreverant. What’s surprising is that Huffington’s rolodex of 250-plus occasional bloggers has managed to fill it with serious, thoughtful discussion. Many of the biggest names have failed to make much use of their soapbox (Norman Mailer has posted twice, Ellen Degeneres only once (about horses), both at the beginning of the run). What has built the site into a popular daily destination is not the promise of star-spun wisdom, but the insight provided by the more dedicated bloggers, many of them lesser-known figures with a great deal of expertise in a given area. What you end up with is a nice mix of opinion, satire, gossip, and serious analysis of current events — a kind of heightened public square.

In yesterday’s Washington Post, against the steady hum of online intrigue about Judy “run-amok” Miller, and the sound of millions of nails being gnawed in anticipation of what hopes to be a major league indictment of Rove and/or Libby, the afore-mentioned Tina Brown observed:

For Arianna Huffington, the Miller story has been to her newly birthed blog, the Huffington Post, a miniature version of what O.J. Simpson was to cable news.

And she’s right. Over this past week, something seems to have crystallized. Amidst all the head-scratching following the Times’ marathon coverage of the Judith Miller imbroglio this Sunday, the bloggers, not the press, have done the better job of cutting through the fog, or at the very least, of keeping our sights on the big picture. The Huffington Post has been particularly on the ball, with Arianna leading the way.

The big picture, of course, is that we are at war. And that The New York Times — the supposed “paper of record” — allowed itself to become part of the propaganda campaign that put us there. It’s the story of an entire news organization that, through one misguided reporter, got too “embedded” with its sources and totally lost its perspective. This is not the self-contained sort of scandal we saw with Jayson Blair. Nor is it really about some high-minded cause: the right to maintain confidentiality of sources. This is about the lies that led to war.

Unfortunately, we probably know less now about what happened with Judith Miller than we did before she delivered her mystifying testimonial on Sunday (aspens! clusters!). But the rigorous work-through the story has received around the blogosphere, and from a handful of columnists in the mainstream press, has defined the larger moral frame, keeping the democratic stakes appropriately high (hopes that the Democrats themselves might do the same will almost surely be disappointed).

In an interview with Wired last month, Huffington described what she sees as the problem with cable and online news coverage (increasingly one in the same):

The problem isn’t that the stories I care about aren’t being covered, it’s that they aren’t being covered in the obsessive way that breaks through the din of our 500-channel universe. Because those 500 channels don’t mean we get 500 times the examination and investigation of worthy news stories. It often means we get the same narrow, conventional-wisdom wrap-ups repeated 500 times. Paradoxically, in these days of instant communication and 24-hour news channels, it’s actually easier to miss information we might otherwise pay attention to. That’s why we need stories to be covered and re-covered and re-re-covered and covered again — until they filter up enough to become part of the cultural bloodstream.

The Judygate re-re-coverage on H. Post and throughout the blogosphere emphasizes the redefinition of the news as a two-way medium. The readers are now a major part of the process. What Huffington has done is to aggregate some of the more interesting readers.