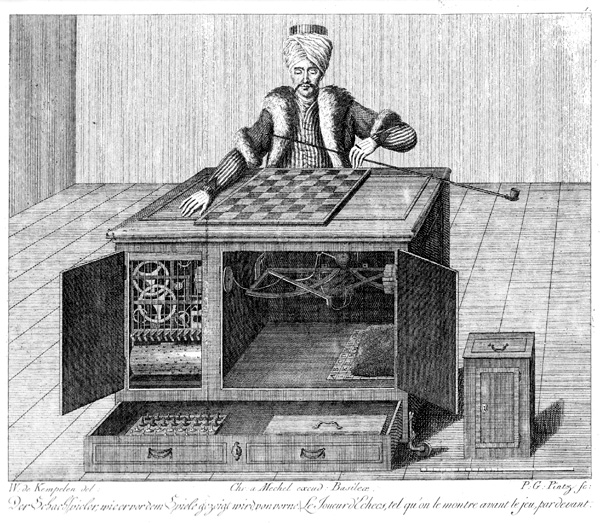

An engraving of The Turk from Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s Inanimate Reason, published in 1784. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

We had Lauren Klein, a graduate student from CUNY, over to lunch this afternoon. One of the pleasures of such a lunch is later looking up conversational asides: today we happened upon the subject of chess machines. Lauren specifically referenced “Maelzel’s Chess Player” by Edgar Allen Poe, Edison’s Eve by Gaby Wood, and The Turk by Tom Standage.

The Turk is a chess-playing machine built in the 18th Century by Wolfgang von Kempelen. What made the machine so astounding was its chess expertise; of course, it was controlled by levers by a person beneath the chessboard, who moved pieces with its hands and could manipulate its facial expressions. The Turk was sold by Kempelen’s son to to Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who added a voice box to the machine (to say “â?°chec!”) and used it to beat Napoleon, according to legend. The machine was eventually contributed to a museum in Philadelphia, where most of it was destroyed in a fire.

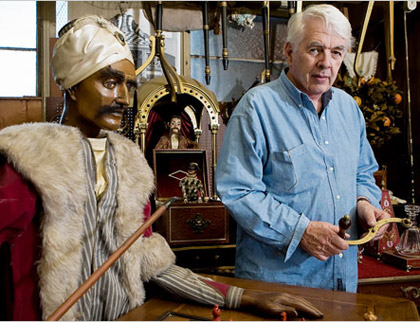

That is, until the pieces came into the hands of John Gaughan, the man who made Gary Sinise’s legs disappear in Forrest Gump and turned a beast into a prince for Disney’s Broadway production of Beauty and the Beast. He salvaged the remains of The Turk and built a version of it that is controlled by computer (for a price tag of about $120,000). As Poe puts it, “Perhaps no exhibition of the kind has ever elicited so general attention as the Chess-Player of Maelzel.”

Image courtesy of The New York Times.

Perhaps the most poignant theme of this story is that it strikes upon some of the things that draw us to technology: spectacle, surprise, a little hint of magic, and the humbling experience of being stumped by something that’s not human.

Category Archives: history_of_interactive_media

“people talk about ‘the future’ being tomorrow, ‘the future’ is now.”

The artist Nam June Paik passed away on Sunday. Paik’s justifiably known as the first video artist, but thinking of him as “the guy who did things with TVs” does him the disservice of neglecting how visionary his thought was – and that goes beyond his coining of the term “electronic superhighway” (in a 1978 report for the Ford Foundation) to describe the increasingly ubiquitous network that surrounds us. Consider as well his vision of Utopian Laser Television, a manifesto from 1962 that argued for

The artist Nam June Paik passed away on Sunday. Paik’s justifiably known as the first video artist, but thinking of him as “the guy who did things with TVs” does him the disservice of neglecting how visionary his thought was – and that goes beyond his coining of the term “electronic superhighway” (in a 1978 report for the Ford Foundation) to describe the increasingly ubiquitous network that surrounds us. Consider as well his vision of Utopian Laser Television, a manifesto from 1962 that argued for

a new communications medium based on hundreds of television channels. Each channel would narrowcast its own program to an audience of those who wanted the program without regard to the size of the audience. It wouldn’t make a difference whether the audience was made of two viewers or two billion. It wouldn’t even matter whether the programs were intelligent or ridiculous, commonly comprehensible or perfectly eccentric. The medium would make it possible for all information to be transmitted and each member of each audience would be free to select or choose his own programming based on a menu of infinitely large possibilities.

(Described by Ken Friedman in “Twelve Fluxus Ideas“.) Paik had some of the particulars wrong – always the bugbear of those who would describe the future – but in essence this is a spot-on description of the Web we know and use every day. The network was the subject of his art, both directly – in his closed-circuit television sculptures, for example – and indirectly, in the thought that informed them. In 1978, he considered the problem of networks of distribution:

Marx gave much thought about the dialectics of the production and the production medium. He had thought rather simply that if workers (producers) OWNED the production’s medium, everything would be fine. He did not give creative room to the DISTRIBUTION system. The problem of the art world in the ’60s and ’70s is that although the artist owns the production’s medium, such as paint or brush, even sometimes a printing press, they are excluded from the highly centralized DISTRIBUTION system of the art world.

George Maciunas‘ Genius is the early detection of this post-Marxistic situation and he tried to seize not only the production’s medium but also the DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM of the art world.

(from “George Maciunas and Fluxus”, Flash Art, quoted in Owen F. Smith’s “Fluxus Praxis: an exploration of connections, creativity and community”.) As it was for the artists, so it is now for the rest of us: the problems of art are now the problems of the Internet. This could very easily be part of the ongoing argument about “who owns the pipes”.

Paik’s questions haven’t gone away, and they won’t be going away any time soon. I suspect that he knew this would be the case: “People talk about ‘the future’ being tomorrow,” he said in an interview with Artnews in 1995, “ ‘the future’ is now.”

mass culture vs technoculture?

It’s the end of the year, and thus time for the jeremiads. In a December 18 Los Angeles Times article, Reed Johnson warns that 2005 was the year when “mass culture” — by which Johnson seemed to mean mass media generally — gave way to a consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution. According to Johnson:

It’s the end of the year, and thus time for the jeremiads. In a December 18 Los Angeles Times article, Reed Johnson warns that 2005 was the year when “mass culture” — by which Johnson seemed to mean mass media generally — gave way to a consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution. According to Johnson:

This was the year in which Hollywood, despite surging DVD and overseas sales, spent the summer brooding over its blockbuster shortage, and panic swept the newspaper biz as circulation at some large dailies went into free fall. Consumers, on the other hand, couldn’t have been more blissed out as they sampled an explosion of information outlets and entertainment options: cutting-edge music they could download off websites into their iPods and take with them to the beach or the mall; customized newcasts delivered straight to their Palm Pilots; TiVo-edited, commercial-free programs plucked from a zillion cable channels. The old mass culture suddenly looked pokey and quaint. By contrast, the emerging 21st century mass technoculture of podcasting, video blogging, the Google Zeitgeist list and “social networking software” that links people on the basis of shared interest in, say, Puerto Rican reggaeton bands seems democratic, consumer-driven, user-friendly, enlightened, opinionated, streamlined and sexy.

Or so it seems, Johnson continues: before we celebrate too much, we need to remember the difference between consumers and citizens. We are technoconsumers, not technocitizens, and as we celebrate our possibilites, we forget that “much of the supposedly independent and free-spirited techno-culture is being engineered (or rapidly acquired) by a handful of media and technology leviathans: News Corp., Apple, Microsoft, Yahoo, and Google, the budding General Motors of the Information Age.”

I hadn’t thought of Google as the GM of the Information Age. I’m not at all sure, actually, that the analogy works, given the different ways in which GM and Google leverage the US economy — fifty years hence, Google plant closures won’t be decimating middle America. But I’m very much behind Johnson’s call for more attention to media consolidation in the age of convergence. Soon, it’s going to be time for the Columbia Journalism Review to add the leviathans listed above to its Who Owns What page, which enables users to track the ownership of most old media products, but currently comes up short in tracking new media. Actually, they should consider updating it as of tomorrow, when the final details of Google’s billion dollar deal for five percent of AOL are made public.

I hadn’t thought of Google as the GM of the Information Age. I’m not at all sure, actually, that the analogy works, given the different ways in which GM and Google leverage the US economy — fifty years hence, Google plant closures won’t be decimating middle America. But I’m very much behind Johnson’s call for more attention to media consolidation in the age of convergence. Soon, it’s going to be time for the Columbia Journalism Review to add the leviathans listed above to its Who Owns What page, which enables users to track the ownership of most old media products, but currently comes up short in tracking new media. Actually, they should consider updating it as of tomorrow, when the final details of Google’s billion dollar deal for five percent of AOL are made public.

multimedia vs intermedia

One of the odd things that strikes me about so much writing about technology is the seeming assumption that technology (and the ideas associated with it) arise from some sort of cultural vacuum. It’s an odd myopia, if not an intellectual arrogance, and it results in a widespream failure to notice many connections that should be obvious. One such connection is that between the work of many of the conceptual artists of the 1960s and continuing attempts to sort out what it means to read when books don’t need to be limited to text & illustrations. (This, of course, is a primary concern of the Institute.)

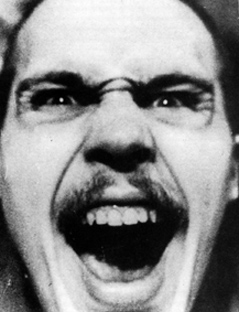

Lately I’ve been delving through the work of Dick Higgins (1938–1998), a self-described “polyartist” who might be most easily situated by declaring him to be a student of John Cage and part of the Fluxus group of artists. This doesn’t quite do him justice: Higgins’s work bounced back and forth between genres of the avant-garde, from music composition (in the rather frightening photo above, he’s performing his Danger Music No. 17, which instructs the performer to scream as loudly as possible for as long as possible) to visual poetry to street theatre. He supported himself by working as a printer: the first of several publishing ventures was the Something Else Press, which he ran from 1963 to 1974, publishing a variety of works by artists and poets as well as critical writing.

“Betweenness” might be taken as the defining quality of his work, and this betweenness is what interests me. Higgins recognized this – he was perhaps as strong a critic as an artist – and in 1964, he coined the term “intermedia” to describe what he & his fellow Fluxus artists were doing: going between media, taking aspects from established forms to create new ones. An example of this might be visual, or concrete poetry, of which that of Jackson Mac Low or Ian Hamilton Finlay – both of whom Higgins published – might be taken as representative. Visual poetry exists as an intermediate form between poetry and graphic design, taking on aspects of both. This is elaborated (in an apposite form) in his poster on poetry & its intermedia; click on the thumbnail to the right to see a (much) larger version with legible type.

“Betweenness” might be taken as the defining quality of his work, and this betweenness is what interests me. Higgins recognized this – he was perhaps as strong a critic as an artist – and in 1964, he coined the term “intermedia” to describe what he & his fellow Fluxus artists were doing: going between media, taking aspects from established forms to create new ones. An example of this might be visual, or concrete poetry, of which that of Jackson Mac Low or Ian Hamilton Finlay – both of whom Higgins published – might be taken as representative. Visual poetry exists as an intermediate form between poetry and graphic design, taking on aspects of both. This is elaborated (in an apposite form) in his poster on poetry & its intermedia; click on the thumbnail to the right to see a (much) larger version with legible type.

Higgins certainly did not imagine he was the first to use the idea of intermedia; he traced the word itself back to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who had used it in the same sense in 1812. The concept has similarities to Richard Wagner’s idea of opera as Gesamkunstwerk, the “total artwork”, combining theatre and music. But Higgins suggested that the roots of the idea could be found in the sixteenth century, in Giordano Bruno’s On the Composition of Signs and Images, which he translated into English and annotated. And though it might be an old idea, a quote from a text about intermedia that he wrote in 1965 (available online at the always reliable Ubuweb) suggests parallels between the avant-garde world Higgins was working in forty years ago and our concern at the Institute, the way the book seems to be changing in the electronic world:

Much of the best work being produced today seems to fall between media. This is no accident. The concept of the separation between media arose in the Renaissance. The idea that a painting is made of paint on canvas or that a sculpture should not be painted seems characteristic of the kind of social thought–categorizing and dividing society into nobility with its various subdivisions, untitled gentry, artisans, serfs and landless workers–which we call the feudal conception of the Great Chain of Being. This essentially mechanistic approach continued to be relevant throughout the first two industrial revolutions, just concluded, and into the present era of automation, which constitutes, in fact, a third industrial revolution.

Higgins isn’t explicitly mentioning the print revolution started by Gutenberg or the corresponding changes in how reading is increasingly moving from the page to the screen, but that doesn’t seem like an enormous leap to make. A chart he made in 1995 diagrams the interactions between various sorts of intermedia:

Note the question marks – Higgins knew there was terrain yet to be mapped out, and an interview suggests that he imagined that the genre-mixing facilitated by the computer might be able to fill in those spaces.

“Multimedia” is something that comes up all the time when we’re talking about what computers do to reading. The concept is simple: you take a book & you add pictures and sound clips and movies. To me it’s always suggested an assemblage of different kinds of media with a rubber band – the computer program or the webpage – around them, an assemblage that usually doesn’t work as a whole because the elements comprising it are too disparate. Higgins’s intermedia is a more appealing idea: something that falls in between forms is more likely to bear scrutiny as a unified object than a collection of objects. The simple equation text + pictures (the simplest and most common way we think about multimedia) is less interesting to me than a unified whole that falls between text and pictures. When you have text + pictures, it’s all too easy to criticize the text and pictures separately: this picture compared to all other possible pictures invariably suffered, just as this text compared to all other possible texts must suffer. Put in other terms, it’s a design failure.

A note added to the essay quoted above in 1981 more explicitly presents the ways in which intermedia can be a useful tool for approaching new work:

It is today, as it was in 1965, a useful way to approach some new work; one asks oneself, “what that I know does this new work lie between?” But it is more useful at the outset of a critical process than at the later stages of it. Perhaps I did not see that at the time, but it is clear to me now. Perhaps, in all the excitement of what was, for me, a discovery, I overvalued it. I do not wish to compensate with a second error of judgment and to undervalue it now. But it would seem that to proceed further in the understanding of any given work, one must look elsewhere–to all the aspects of a work and not just to its formal origins, and at the horizons which the work implies, to find an appropriate hermeneutic process for seeing the whole of the work in my own relation to it.

The last sentence bears no small relevance to new media criticism: while a video game might be kind of like a film or kind of like a book, it’s not simply the sum of its parts. This might be seen as the difference between thinking about terms of multimedia and in terms of intermedia. We might use it as a guideline for thinking about the book to come, which isn’t a simple replacement for the printed book, but a new form entirely. While we can think about the future book as incorporating existing pieces – text, film, pictures, sound – we will only really be able to appreciate these objects when we find a way to look at them as a whole.

An addendum: “Intermedia” got picked up as the name of a hypertext project out of Brown started in 1985 that Ted Nelson, among others, was involved with. It’s hard to tell whether it was thus named because of familiarity with Higgins’s work, but I suspect not: these two threads, the technologic and the artistic, seem to be running in parallel. But this isn’t necessarily, as is commonly suuposed, because the artists weren’t interested in technical possibilities. Higgins’s Book of Love & Death & War, published in 1972, might merit a chapter in the history of books & computers: a book-length aleatory poem, he notes in his preface that one of its cantos was composed with the help of a FORTRAN IV program that he wrote to randomize its lines. (Canto One of the poem is online at Ubuweb; this is not, however, the computer-generated part of the work.)

And another addendum: something else to take from Higgins might be his resistance to commodification. Because his work fell between the crevices of recognized forms, it couldn’t easily be marketed: how would you go about selling his metadramas, for example? It does, however, appear perfectly suited for the web & perhaps this resistance to commodification is apropos right now, in the midst of furious debates about whether information wants to be free or not. “The word,” notes Higgins in one of his Aphorisms for a Rainy Day in the poster above, “is not dead, it is merely changing its skin.”

powerpoint in transition

Hi, this is from Ray Cha, and I’ve just joined the folks at the Institute after working in various areas of commerical and educational new media. I also spend a lot of time thinking about the interplay between culture and technology. I read a small tidbit in this week’s Time magazine about PowerPoint and thought it would be a good topic for my first post.

Whether you love it (David Byrne) or hate it (Edward Tufte), PowerPoint is the industry standard presentation tool. Microsoft is gearing up to launch its long overdue PowerPoint upgrade in 2006. Time reports 400 million people use the application, and in a single day, 30 million presentations are given using it. Although the PowerPoint handout is still common, presentations are commonly created and showed only in a digital format. The presentation is a great example of how a medium goes through the process of becoming digitized.

When Microsoft purchased PowerPoint and its creator Forethought in 1987, presentations were shown on the once standard overhead projector and acetate slides. With PowerPoint’s Windows and DOS release, the software quickly replaced painstaking tedious letter transfers. However, PowerPoint presentations were still printed on expensive transparencies to be used with overhead projectors throughout the 1990s. As digital projectors became less expensive and more common in conference rooms, acetate slides became a rarity as the hand written letter did in the age of email.

Presentations were an obvious candidate to pioneer the transition into digital text. As stated, presentations were time intensive and expensive to produce and are often given off site. Therefore, a demand existed to improve on the standard way of creating and delivering presentations. I will also go out on a limb and also suggest that people did not have the emotional connection as they do with books, making the transition easier. In terms of the technological transfer, presentation creators already had desktop computers when PowerPoint was released with MS Office in 1990. By printing their PowerPoint output onto transparencies, display compatibility was not an issue. The PowerPoint user base could grow as the digital projector market expanded more slowly. This growth encouraged organizations to adapt to digital projectors as well. Overhead and digital projectors are a shared resource, therefore an organization only needs one project per conference room. These factors lead to fast track adoption. In contrast, ebook hardware is not efficiently shared, people have an emotional bond with paper-based books, and far fewer people write books than presentations. Only when handheld displays become as common and functional as mobile phones, will the days of paper handouts will be numbered.

Moving to a digital format has negative effects as mentioned by critics such as Tufte. Transferring each letter by hand did encourage text to concise and to the point. Also, transparencies were expensive as compared to PowerPoint slides, where the cost of the marginal slide is effectively zero, which is why we are often subjected to painstakingly long PowerPoint presentation. Although, these same critics argue that valuable time is wasted now in the infinite fiddling that occurs in the production of PowerPoint presentations at the expense of thinking about and developing content.

The development of the digital presentation begins to show the factors required to transfer text into a digital medium. Having an existing user base, a clear advantage in terms of cost and capability, the ability to allow users to use existing technology to either create or display the text, all start to reveal insight on how a printed text transforms into a digital medium.

questions and answers

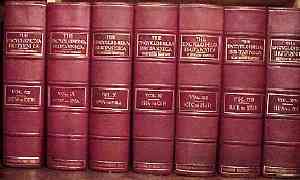

in 1980 and 81 i had a dream job — charlie van doren, the editorial director of Encyclopedia Britannica, hired me to think about the future of encyclopedias in the digital era.  i parlayed that gig into an eighteen-month stint with Alan Kay when he was the chief scientist at Atari. Alan had read the paper i wrote for britannica — EB and the Intellectual Tools of the Future — and in his enthusiastic impulsive style, said, “this is just the sort of thing i want to work on, why not join me at Atari.”

i parlayed that gig into an eighteen-month stint with Alan Kay when he was the chief scientist at Atari. Alan had read the paper i wrote for britannica — EB and the Intellectual Tools of the Future — and in his enthusiastic impulsive style, said, “this is just the sort of thing i want to work on, why not join me at Atari.”

while we figured that the future encyclopedia should at the least be able to answer most any factual question someone might have, we really didn’t have any idea of the range of questions people would ask. we reasoned that while people are curious by nature, they fall out of the childhood habit of asking questions about anything and everything because they get used to the fact that no one in their immediate vicinity actually knows or can explain the answer and the likelihood of finding the answer in a readily available book isn’t much greater.

so, as an experiment we gave a bunch of people tape recorders and asked them to record any question that came to mind during the day — anything. we started collecting question journals in which people whispered their wonderings — both the mundane and the profound. michael naimark, a colleague at Atari was particularly fascinated by this project and he went to the philippines to gather questions from a mountain tribe.

anyway, this is a long intro to the realization that between wikipedia and google, alan’s and my dream of a universal question/answer machine is actually coming into being. although we could imagine what it would be like to have the ability to get answers to most any question, we assumed that the foundation would be a bunch of editors responsible for the collecting and organizing vast amounts of information. we didnt’ imagine the world wide web as a magnet which would motivate people collectively to store a remarkable range of human knowledge in a searchable database.

anyway, this is a long intro to the realization that between wikipedia and google, alan’s and my dream of a universal question/answer machine is actually coming into being. although we could imagine what it would be like to have the ability to get answers to most any question, we assumed that the foundation would be a bunch of editors responsible for the collecting and organizing vast amounts of information. we didnt’ imagine the world wide web as a magnet which would motivate people collectively to store a remarkable range of human knowledge in a searchable database.

on the other hand we assumed that the encylopedia of the future would be intelligent enough to enter into conversation with individual users, helping them through rough spots like a patient tutor. looks like we’ll have to wait awhile for that.

learning from failure: the dot com archive

The University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business is building an archive of primary source documents related to the dot com boom and bust. The Business Plan Archive contains business plans, marketing plans, venture presentations and other business documents from thousands of failed and successful Internet start-ups. In the upcoming second phase of the project, the archive’s creator, assistant professor David A. Kirsch, will collect oral histories from investors, entrepreneurs, and workers, in order to create a complete picture of the so-called internet bubble.

With support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, The Library of Congress, and Maryland’s business school, Mr. Kirsch is creating a teaching tool as well as an historical archive. Students in his management and organization courses at Maryland’s School of Business, must choose a company from the archive and analyze what went wrong (or right). Scholars and students at other institutions are also using it for course assignments and research.

An article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Creating an Archive of Failed Dot-Coms, points out that Mr. Kirsch won’t profit much, despite the success of the archive.

Mr. Kirsch concedes that spending his time building an online archive might not be the best marketing strategy for an assistant professor who would like to earn tenure and a promotion. Online scholarship, he says, does not always generate the same respect in academic circles that publishing hardcover books does.

“My database has 39,000 registered users from 70 countries,” he says. “If that were my book sales, it would be the best-selling academic book of the year.”

Even so, Mr. Kirsch believes, the archive fills an important role in preserving firsthand materials.

“Archivists and scholars normally wait around for the records of the past to cascade down through various hands to the netherworld of historical archives,” he says. “With digital records, we can’t afford to wait.”

wiki wiki: snapshot etymology

Found on Flickr: the famous “wiki wiki” shuttle bus at the Honolulu airport. In Hawaiian pidgin, “wiki wiki” means “quick,” or “informal,” and is what inspired Ward Cunningham in 1995 to name his new openly editable web document engine “wiki”, or the WikiWikiWeb.

(photo by cogdogblog)

stacking up HyperCard

Nick Montfort (over at Grand Text Auto) aims to compile a comprehensive directory of works built in the now-legendary HyperCard – the graphical, card-based application that popularized hypermedia and jumpstarted the first big wave of popular electronic authoring. The HyperCard Bibliography is far from complete, but Nick has placed it in the public domain, inviting everyone to make additions. Among the “noted omissions” are the Expanded Book Series and CD-ROMs from the Voyager Company (pictured here is a card from Robert Winter’s Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 CD Companion). A selection of these titles can be viewed on the institute’s exhibitions page. Thanks, Nick!

Nick Montfort (over at Grand Text Auto) aims to compile a comprehensive directory of works built in the now-legendary HyperCard – the graphical, card-based application that popularized hypermedia and jumpstarted the first big wave of popular electronic authoring. The HyperCard Bibliography is far from complete, but Nick has placed it in the public domain, inviting everyone to make additions. Among the “noted omissions” are the Expanded Book Series and CD-ROMs from the Voyager Company (pictured here is a card from Robert Winter’s Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 CD Companion). A selection of these titles can be viewed on the institute’s exhibitions page. Thanks, Nick!

For more background on this period, visit Smackeral’s “When Multimedia Was Black & White.”

from aspen to A9

Amazon’s search engine A9 has recently unveiled a new service: yellow pages “like you’ve never seen before.”

“Using trucks equipped with digital cameras, global positioning system (GPS) receivers, and proprietary software and hardware, A9.com drove tens of thousands of miles capturing images and matching them with businesses and the way they look from the street.”

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

I can imagine online services like Mapquest getting into, or wanting to get into, this kind of image-banking. But I wouldn’t expect trucks with camera mounts to become a common sight on city streets. More likely, A9 is building up a first-run image bank to demonstrate what is possible. As people catch on, it would seem only natural that they would start accepting user contributions.  Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

A9’s new service does have a predecessor though, and it’s nearly 30 years old. In the late 70s, the Architecture Machine Group, which later morphed into the MIT Media Lab, developed some of the first prototypes of “interactive media.” Among them was the Aspen Movie Map, developed in 1978-79 by Andrew Lippman – a program that allowed the user to navigate the entirety of this small Colorado city, in whatever order they chose, in winter, spring, summer or fall, and even permitting them to enter many of the buildings. The Movie Map is generally viewed as the first truly interactive computer program. Now, with the explosion of digital photography, wireless networked devices, and image-caching across social networks, we might at last be nearing its realization on a grand scale.