Last night I attended a fascinating panel discussion at the American Bar Association on the legality of Google Book Search. In many ways, this was the debate made flesh. Making the case against Google were high-level representatives from the two entities that have brought suit, the Authors’ Guild (Executive Director Paul Aiken) and the Association of American Publishers (VP for legal counsel Allan Adler). It would have been exciting if Google, in turn, had sent representatives to make their case, but instead we had two independent commentators, law professor and blogger Susan Crawford and Cameron Stracher, also a law professor and writer. The discussion was vigorous, at times heated — in many ways a preview of arguments that could eventually be aired (albeit under a much stricter clock) in front of federal judges.

The lawsuits in question center around whether Google’s scanning of books and presenting tiny snippet quotations online for keyword searches is, as they claim, fair use. As I understand it, the use in question is the initial scanning of full texts of copyrighted books held in the collections of partner libraries. The fair use defense hinges on this initial full scan being the necessary first step before the “transformative” use of the texts, namely unbundling the book into snippets generated on the fly in response to user search queries.

…in case you were wondering what snippets look like

At first, the conversation remained focused on this question, and during that time it seemed that Google was winning the debate. The plaintiffs’ arguments seemed weak and a little desperate. Aiken used carefully scripted language about not being against online book search, just wanting it to be licensed, quipping “we’re just throwing a little gravel in the gearbox of progress.” Adler was a little more strident, calling Google “the master of misdirection,” using the promise of technological dazzlement to turn public opinion against the legitimate grievances of publishers (of course, this will be settled by judges, not by public opinion). He did score one good point, though, saying Google has betrayed the weakness of its fair use claim in the way it has continually revised its description of the program.

Almost exactly one year ago, Google unveiled its “library initiative” only to re-brand it several months later as a “publisher program” following a wave of negative press. This, however, did little to ease tensions and eventually Google decided to halt all book scanning (until this past November) while they tried to smooth things over with the publishers. Even so, lawsuits were filed, despite Google’s offer of an “opt-out” option for publishers, allowing them to request that certain titles not be included in the search index. This more or less created an analog to the “implied consent” principle that legitimates search engines caching web pages with “spider” programs that crawl the net looking for new material.

In that case, there is a machine-to-machine communication taking place and web page owners are free to insert programs that instruct spiders not to cache, or can simply place certain content behind a firewall. By offering an “opt-out” option to publishers, Google enables essentially the same sort of communication. Adler’s point (and this was echoed more succinctly by a smart question from the audience) was that if Google’s fair use claim is so air-tight, then why offer this middle ground? Why all these efforts to mollify publishers without actually negotiating a license? (I am definitely concerned that Google’s efforts to quell what probably should have been an anticipated negative reaction from the publishing industry will end up undercutting its legal position.)

Crawford came back with some nice points, most significantly that the publishers were trying to make a pretty egregious “double dip” into the value of their books. Google, by creating a searchable digital index of book texts — “a card catalogue on steroids,” as she put it — and even generating revenue by placing ads alongside search results, is making a transformative use of the published material and should not have to seek permission. Google had a good idea. And it is an eminently fair use.

And it’s not Google’s idea alone, they just had it first and are using it to gain a competitive advantage over their search engine rivals, who in their turn, have tried to get in on the game with the Open Content Alliance (which, incidentally, has decided not to make a stand on fair use as Google has, and are doing all their scanning and indexing in the context of license agreements). Publishers, too, are welcome to build their own databases and to make them crawl-able by search engines. Earlier this week, Harper Collins announced it would be doing exactly that with about 20,000 of its titles. Aiken and Adler say that if anyone can scan books and make a search engine, then all hell will break loose and millions of digital copies will be leaked into the web. Crawford shot back that this lawsuit is not about net security issues, it is about fair use.

But once the security cat was let out of the bag, the room turned noticeably against Google (perhaps due to a preponderance of publishing lawyers in the audience). Aiken and Adler worked hard to stir up anxiety about rampant ebook piracy, even as Crawford repeatedly tried to keep the discussion on course. It was very interesting to hear, right from the horse’s mouth, that the Authors’ Guild and AAP both are convinced that the ebook market, tiny as it currently is, is within a few years of exploding, pending the release of some sort of ipod-like gadget for text. At that point, they say, Google will have gained a huge strategic advantage off the back of appropriated content.

Their argument hinges on the fourth determining factor in the fair use exception, which evaluates “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” So the publishers are suing because Google might be cornering a potential market!!! (Crawford goes further into this in her wrap-up) Of course, if Google wanted to go into the ebook business using the material in their database, there would have to be a licensing agreement, otherwise they really would be pirating. But the suits are not about a future market, they are about creating a search service, which should be ruled fair use. If publishers are so worried about the future ebook market, then they should start planning for business.

To echo Crawford, I sincerely hope these cases reach the court and are not settled beforehand. Larger concerns about Google’s expansionist program aside, I think they have made a very brave stand on the principle of fair use, the essential breathing space carved out within our over-extended copyright laws. Crawford reminded the room that intellectual property is NOT like physical property, over which the owner has nearly unlimited rights. Copyright is a “temporary statutory monopoly” originally granted (“with hesitation,” Crawford adds) in order to incentivize creative expression and the production of ideas. The internet scares the old-guard publishing industry because it poses so many threats to the security of their product. These threats are certainly significant, but they are not the subject of these lawsuits, nor are they Google’s, or any search engine’s, fault. The rise of the net should not become a pretext for limiting or abolishing fair use.

Category Archives: google

where we’ve been, where we’re going

This past week at if:book we’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between this weblog and the work we do. We decided that while if:book has done a fine job reflecting and provoking the conversations we have at the Institute, we wanted to make sure that it also seems as coherent to our readers as it does to us. With that in mind, we’ve decided to begin posting a weekly roundup of our blog posts, in which we synthesize (as much a possible) what we’ve been thinking and talking about from Monday to Friday.

So here goes. This week we spent a lot of time reflecting on simulation and virtuality. In part, this reflection grew out of our collective reading of a Tom Zengotita’s book Mediated, which discusses (among other things) the link between alienation from the “real” through digital mediation and increased solipsism. Bob seemed especially interested in the dialectic relationship between, on one hand, the opportunity for access afforded by ever-more sophisticated form of simulation, and, on the other, the sense that something must be lost when as the encounter with the “real” recedes entirely.

This, in turn, led to further conversation about what we might think of as the “loss of the real” in the transition from books on paper to books on a computer screen. On one hand, there seems to be a tremendous amount of anxiety that Google Book Search might somehow make actual books irrelevant and thus destroy reading and writing practices linked to the bound book. On the other hand, one could take the position of Cory Doctorow that books as objects are overrated, and challenge the idea that a book needs to be digitally embodied to be “real.”

As the debate over Google Book Search continually reminds us, one of the most challenging things in sifting through discussions of emerging media forms is learning to tell the difference between nostalgia and useful critical insight. Often the two are hopelessly intertwined; in this week’s debates about Wikipedia, for example, discussion of how to make the open-source encyclopedia more useful was often tempered by the suggestion that encyclopedias of the past were always be superior to Wikipedia, an assertion easily challenged by a quick browse through some old encyclopedias.

Finally, I want to mention that we finally got around to setting up a del.icio.us account. There will be a formal link on the blog up soon, but you can take a look now. It will expand quickly.

google libraries podcast now available

google on the air

Open Source’s hour on the Googlization of libraries was refreshingly light on the copyright issue and heavier on questions about research, reading, the value of libraries, and the public interest. With its book-scanning project, Google is a private company taking on the responsibilities of a public utility, and Siva Vaidhyanathan came down hard on one of the company’s chief legal reps for the mystery shrouding their operations (scanning technology, algorithms and ranking system are all kept secret). The rep reasonably replied that Google is not the only digitization project in town and that none of its library partnerships are exclusive. But most of his points were pretty obvious PR boilerplate about Google’s altruism and gosh darn love of books. Hearing the counsel’s slick defense, your gut tells you it’s right to be suspicious of Google and to keep demanding more transparency, clearer privacy standards and so on. If we’re going to let this much information come into the hands of one corporation, we need to be very active watchdogs.

Our friend Karen Schneider then joined the fray and as usual brought her sage librarian’s perspective. She’s thrilled by the possibilities of Google Book Search, seeing as it solves the fundamental problem of library science: that you can only search the metadata, not the texts themselves. But her enthusiasm is tempered by concerns about privatization similar to Siva’s and a conviction that a research service like Google can never replace good librarianship and good physical libraries. She also took issue with the fact that Book Search doesn’t link to other library-related search services like Open Worldcat. She has her own wrap-up of the show on her blog.

Rounding out the discussion was Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, a cybertext studies blogger and professor of english at the University of Maryland. Kirschenbaum addressed the question of how Google, and the web in general, might be changing, possibly eroding, our reading practices. He nicely put the question in perspective, suggesting that scattershot, inter-textual, “snippety” reading is in fact the older kind of reading, and that the idea of sustained, deeply immersed involvement with a single text is largely a romantic notion tied to the rise of the novel in the 18th century.

A satisfying hour, all in all, of the sort we should be having more often. It was fun brainstorming with Brendan Greeley, the Open Source on “blogger-in-chief,” on how to put the show together. Their whole bit about reaching out to the blogosphere for ideas and inspiration isn’t just talk. They put their money where their mouth is. I’ll link to the podcast when it becomes available.

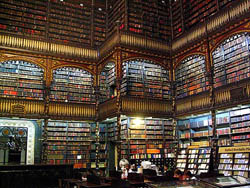

image: Real Gabinete Português de Literatura, Rio de Janeiro – Claudio Lara via Flickr

thinking about google books: tonight at 7 on radio open source

While visiting the Experimental Television Center in upstate New York this past weekend, Lisa found a wonderful relic in a used book shop in Owego, NY — a small, leatherbound volume from 1962 entitled “Computers,” which IBM used to give out as a complimentary item. An introductory note on the opening page reads:

The machines do not think — but they are one of the greatest aids to the men who do think ever invented! Calculations which would take men thousands of hours — sometimes thousands of years — to perform can be handled in moments, freeing scientists, technicians, engineers, businessmen, and strategists to think about using the results.

This echoes Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 essay on computing and networked knowledge, “As We May Think”, which more or less prefigured the internet, web search, and now, the migration of print libraries to the world wide web. Google Book Search opens up fantastic possibilities for research and accessibility, enabling readers to find in seconds what before might have taken them hours, days or weeks. Yet it also promises to transform the very way we conceive of books and libraries, shaking the foundations of major institutions. Will making books searchable online give us more time to think about the results of our research, or will it change the entire way we think? By putting whole books online do we begin the steady process of disintegrating the idea of the book as a bounded whole and not just a sequence of text in a massive database?

The debate thus far has focused too much on the legal ramifications — helped in part by a couple of high-profile lawsuits from authors and publishers — failing to take into consideration the larger cognitive, cultural and institutional questions. Those questions will hopefully be given ample air time tonight on Radio Open Source.

Tune in at 7pm ET on local public radio or stream live over the web. The show will also be available later in the week as a podcast.

the role of note taking in the information age

An article by Ann Blair in a recent issue of Critical Inquiry (vol 31 no 1) discusses the changing conceptions of the function of note-taking from about the sixth century to the present, and ends with a speculation on the way that textual searches (such as Google Book Search) might change practices of note-taking in the twenty-first century. Blair argues that “one of the most significant shifts in the history of note taking” occured in the beginning of the twentieth century, when the use of notes as memorization aids gave way to the use of notes as a aid to replace the memorization of too-abundant information. With the advent of the net, she notes:

Today we delegate to sources that we consider authoritative the extraction of information on all but a few carefully specialized areas in which we cultivate direct experience and original research. New technologies increasingly enable us to delegate more tasks of remembering to the computer, in that shifting division of labor between human and thing. We have thus mechanized many research tasks. It is possible that further changes would affect even the existence of note taking. At a theoretical extreme, for example, if every text one wanted were constantly available for searching anew, perhaps the note itself, the selection made for later reuse, might play a less prominent role.

The result of this externalization, Blair notes, is that we come to think of long-term memory as something that is stored elsewhere, in “media outside the mind.” At the same time, she writes, “notes must be rememorated or absorbed in the short-term memory at least enough to be intelligently integrated into an argument; judgment can only be applied to experiences that are present to the mind.”

Blair’s article doesn’t say that this bifurcation between short-term and long-term memory is a problem: she simply observes it as a phenomenon. But there’s a resonance between Blair’s article and Naomi Baron’s recent Los Angeles Times piece on Google Book Search: both point to the fact that what we commonly have defined as scholarly reflection has increasingly become more and more a process of database management. Baron seems to see reflection and database management as being in tension, though I’m not completely convinced by her argument. Blair, less apocalyptic than Baron, nonetheless gives me something to ponder. What happens to us if (or when) all of our efforts to make the contents of our extrasomatic memory “present to our mind” happen without the mediation of notes? Blair’s piece focuses on the epistemology rather than the phenomenology of note taking — still, she leads me to wonder what happens if the mediating function of the note is lost, when the triangular relation between book, scholar and note becomes a relation between database and user.

google print on deck at radio open source

Open Source, the excellent public radio program (not to be confused with “Open Source Media”) that taps into the blogosphere to generate its shows, has been chatting with me about putting together an hour on the Google library project. Open Source is a unique hybrid, drawing on the best qualities of the blogosphere — community, transparency, collective wisdom — to produce an otherwise traditional program of smart talk radio. As host Christopher Lydon puts it, the show is “fused at the brain stem with the world wide web.” Or better, it “uses the internet to be a show about the world.”

The Google show is set to air live this evening at 7pm (ET) (they also podcast). It’s been fun working with them behind the scenes, trying to figure out the right guests and questions for the ideal discussion on Google and its bookish ambitions. My exchange has been with Brendan Greeley, the Radio Open Source “blogger-in-chief” (he’s kindly linked to us today on their site). We agreed that the show should avoid getting mired in the usual copyright-focused news peg — publishers vs. Google etc. — and focus instead on the bigger questions. At my suggestion, they’ve invited Siva Vaidhyanathan, who wrote the wonderful piece in the Chronicle of Higher Ed. that I talked about yesterday (see bigger questions). I’ve also recommended our favorite blogger-librarian, Karen Schneider (who has appeared on the show before), science historian George Dyson, who recently wrote a fascinating essay on Google and artificial intelligence, and a bunch of cybertext studies people: Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, N. Katherine Hayles, Jerome McGann and Johanna Drucker. If all goes well, this could end up being a very interesting hour of discussion. Stay tuned.

UPDATE: Open Source just got a hold of Nicholas Kristof to do an hour this evening on Genocide in Sudan, so the Google piece will be pushed to next week.

sober thoughts on google: privatization and privacy

Siva Vaidhyanathan has written an excellent essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education on the “risky gamble” of Google’s book-scanning project — some of the most measured, carefully considered comments I’ve yet seen on the issue. His concerns are not so much for the authors and publishers that have filed suit (on the contrary, he believes they are likely to benefit from Google’s service), but for the general public and the future of libraries. Outsourcing to a private company the vital task of digitizing collections may prove to have been a grave mistake on the part of Google’s partner libraries. Siva:

The long-term risk of privatization is simple: Companies change and fail. Libraries and universities last…..Libraries should not be relinquishing their core duties to private corporations for the sake of expediency. Whichever side wins in court, we as a culture have lost sight of the ways that human beings, archives, indexes, and institutions interact to generate, preserve, revise, and distribute knowledge. We have become obsessed with seeing everything in the universe as “information” to be linked and ranked. We have focused on quantity and convenience at the expense of the richness and serendipity of the full library experience. We are making a tremendous mistake.

This essay contains in abundance what has largely been missing from the Google books debate: intellectual courage. Vaidhyanathan, an intellectual property scholar and “avowed open-source, open-access advocate,” easily could have gone the predictable route of scolding the copyright conservatives and spreading the Google gospel. But he manages to see the big picture beyond the intellectual property concerns. This is not just about economics, it’s about knowledge and the public interest.

What irks me about the usual debate is that it forces you into a position of either resisting Google or being its apologist. But this fails to get at the real bind we all are in: the fact that Google provides invaluable services and yet is amassing too much power; that a private company is creating a monopoly on public information services. Sooner or later, there is bound to be a conflict of interest. That is where we, the Google-addicted public, are caught. It’s more complicated than hip versus square, or good versus evil.

Here’s another good piece on Google. On Monday, The New York Times ran an editorial by Adam Cohen that nicely lays out the privacy concerns:

Google says it needs the data it keeps to improve its technology, but it is doubtful it needs so much personally identifiable information. Of course, this sort of data is enormously valuable for marketing. The whole idea of “Don’t be evil,” though, is resisting lucrative business opportunities when they are wrong. Google should develop an overarching privacy theory that is as bold as its mission to make the world’s information accessible – one that can become a model for the online world. Google is not necessarily worse than other Internet companies when it comes to privacy. But it should be doing better.

Two graduate students in Stanford in the mid-90s recognized that search engines would the most important tools for dealing with the incredible flood of information that was then beginning to swell, so they started indexing web pages and working on algorithms. But as the company has grown, Google’s admirable-sounding mission statement — “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” — has become its manifest destiny, and “information” can now encompass the most private of territories.

At one point it simply meant search results — the answers to our questions. But now it’s the questions as well. Google is keeping a meticulous record of our clickstreams, piecing together an enormous database of queries, refining its search algorithms and, some say, even building a massive artificial brain (more on that later). What else might they do with all this personal information? To date, all of Google’s services are free, but there may be a hidden cost.

“Don’t be evil” may be the company motto, but with its IPO earlier this year, Google adopted a new ideology: they are now a public corporation. If web advertising (their sole source of revenue) levels off, then investors currently high on $400+ shares will start clamoring for Google to maintain profits. “Don’t be evil to us!” they will cry. And what will Google do then?

images: New York Public Library reading room by Kalloosh via Flickr; archive of the original Google page

flushing the net down the tubes

Grand theories about upheavals on the internet horizon are in ready supply. Singularities are near. Explosions can be expected in the next six to eight months. Or the whole thing might just get “flushed” down the tubes. This last scenario is described at length in a recent essay in Linux Journal by Doc Searls, which predicts the imminent hijacking of the net by phone and cable companies who will turn it into a top-down, one-way broadcast medium. In other words, the net’s utopian moment, the “read/write” web, may be about to end. Reading Searls’ piece, I couldn’t help thinking about the story of radio and a wonderful essay Brecht wrote on the subject in 1932:

Here is a positive suggestion: change this apparatus over from distribution to communication. The radio would be the finest possible communication apparatus in public life, a vast network of pipes. That is to say, it would be if it knew how to receive as well as to transmit, how to let the listener speak as well as hear, how to bring him into a relationship instead of isolating him. On this principle the radio should step out of the supply business and organize its listeners as suppliers….turning the audience not only into pupils but into teachers.

Unless you’re the military, law enforcement, or a short-wave hobbyist, two-way radio never happened. On the mainstream commercial front, radio has always been about broadcast: a one-way funnel. The big FM tower to the many receivers, “prettifying public life,” as Brecht puts it. Radio as an agitation? As an invitation to a debate, rousing families from the dinner table into a critical encounter with their world? Well, that would have been neat.

Now there’s the internet, a two-way, every-which-way medium — a stage of stages — that would have positively staggered a provocateur like Brecht. But although the net may be a virtual place, it’s built on some pretty actual stuff. Copper wire, fiber optic cable, trunks, routers, packets — “the vast network of pipes.” The pipes are owned by the phone and cable companies — the broadband providers — and these guys expect a big return (far bigger than they’re getting now) on the billions they’ve invested in laying down the plumbing. Searls:

The choke points are in the pipes, the permission is coming from the lawmakers and regulators, and the choking will be done….The carriers are going to lobby for the laws and regulations they need, and they’re going to do the deals they need to do. The new system will be theirs, not ours….The new carrier-based Net will work in the same asymmetrical few-to-many, top-down pyramidal way made familiar by TV, radio, newspapers, books, magazines and other Industrial Age media now being sucked into Information Age pipes. Movement still will go from producers to consumers, just like it always did.

If Brecht were around today I’m sure he would have already written (or blogged) to this effect, no doubt reciting the sad fate of radio as a cautionary tale. Watch the pipes, he would say. If companies talk about “broad” as in “broadband,” make sure they’re talking about both ends of the pipe. The way broadband works today, the pipe running into your house dwarfs the one running out. That means more download and less upload, and it’s paving the way for a content delivery platform every bit as powerful as cable on an infinitely broader band. Data storage, domain hosting — anything you put up there — will be increasingly costly, though there will likely remain plenty of chat space and web mail provided for free, anything that allows consumers to fire their enthusiasm for commodities through the synapse chain.

If the net goes the way of radio, that will be the difference (allow me to indulge in a little dystopia). Imagine a classic Philco cathedral radio but with a few little funnel-ended hoses extending from the side that connect you to other listeners. “Tune into this frequency!” “You gotta hear this!” You whisper recommendations through the tube. It’s sending a link. Viral marketing. Yes, the net will remain two-way to the extent that it helps fuel the market. Web browsers, like the old Philco, would essentially be receivers, enabling participation only to the extent that it encouraged others to receive.

If the net goes the way of radio, that will be the difference (allow me to indulge in a little dystopia). Imagine a classic Philco cathedral radio but with a few little funnel-ended hoses extending from the side that connect you to other listeners. “Tune into this frequency!” “You gotta hear this!” You whisper recommendations through the tube. It’s sending a link. Viral marketing. Yes, the net will remain two-way to the extent that it helps fuel the market. Web browsers, like the old Philco, would essentially be receivers, enabling participation only to the extent that it encouraged others to receive.

You might even get your blog hosted for free if you promote products — a sports shoe with gelatinous heels or a music video that allows you to undress the dancing girls with your mouse. Throw in some political rants in between to blow off some steam, no problem. That’s entrepreneurial consumerism. Make a living out of your appetites and your ability to make them infectious. Hip recommenders can build a cosy little livelihood out of their endorsements. But any non-consumer activity will be more like amateur short-wave radio: a mildly eccentric (and expensive) hobby (and they’ll even make a saccharine movie about a guy communing with his dead firefighter dad through a ghost blog).

Searls sees it as above all a war of language and metaphor. The phone and cable companies will dominate as long as the internet is understood fundamentally as a network of pipes, a kind of information transport system. This places the carriers at the top of the hierarchy — the highway authority setting the rules of the road and collecting the tolls. So far the carriers have managed, through various regulatory wrangling and court rulings, to ensure that the “transport metaphor” has prevailed.

But obviously the net is much more than the sum of its pipes. It’s a public square. It’s a community center. It’s a market. And it’s the biggest publishing system the world has ever known. Searls wants to promote “place metaphors” like these. Sure, unless you’re a lobbyist for Verizon or SBC, you probably already think of it this way. But in the end it’s the lobbyists that will make all the difference. Unless, that is, an enlightened citizens’ lobby begins making some noise. So a broad, broad as in broadband, public conversation should be in order. Far broader than what goes on in the usual progressive online feedback loops — the Linux and open source communities, the creative commies, and the techno-hip blogosphere, that I’m sure are already in agreement about this.

Google also seems to have an eye on the pipes, reportedly having bought thousands of miles of “dark fiber” — pipe that has been laid but is not yet in use. Some predict a nationwide “Googlenet.” But this can of worms is best saved for another post.

virtual libraries, real ones, empires

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Libraries are inherently islands of freedom and antidotes to fanaticism. They are temples of pluralism where books that contradict one another stand peacefully side by side just as intellectual antagonists work peacefully next to each other in reading rooms. It is legitimate and in our nation’s interest that the new technology be used internationally, both by the private sector to promote economic enterprise and by the public sector to promote democratic institutions. But it is also necessary that America have a more inclusive foreign cultural policy — and not just to blunt charges that we are insensitive cultural imperialists. We have an opportunity and an obligation to form a private-public partnership to use this new technology to celebrate the cultural variety of the world.

What’s interesting about this quote (among other things) is that Billington seems to be suggesting that a World Digital Library would function in much the same manner as a real-world library, and yet he’s also arguing for the importance of actual physical proximity. He writes, after all, about books literally, not virtually, touching each other, and about researchers meeting up in a shared reading room. There seems to be a tension here, in other words, between Billington’s embrace of the idea of a world digital library, and a real anxiety about what a “library” becomes when it goes online.

I also feel like there’s some tension here — in Billington’s editorial and in the whole World Digital Library project — between “inclusiveness” and “imperialism.” Granted, if the United States provides Brazilians access to their own national literature online, this might be used by some as an argument against the idea that we are “insensitive cultural imperialists.” But there are many varieties of empire: indeed, as many have noted, the sun stopped setting on Google’s empire a while ago.

To be clear, I’m not attacking the idea of the World Digital Library. Having watch the Smithsonian invest in, and waffle on, some of their digital projects, I’m all for a sustained commitment to putting more material online. But there needs to be some careful consideration of the differences between online libraries and virtual ones — as well as a bit more discussion of just what a privately-funded digital library might eventually morph into.