“Fuel prices jumped this week, led by gasoline which gained over a dollar a gallon on average. Oil distributors pointed to several “renegotiated” delivery contracts as proof that a long-rumored shortfall in the supply of U.S. oil has finally arrived. Oil producers were tight-lipped about the adjusted contracts, and as I write this it’s still unclear how extensive the shortfall will turn out to be.”

And thus the stage is set for World Without Oil, the social consciousness-raising ARG (alternate reality game) launched today by Jane McGonigal and associates. I’m already in flagrant violation of the “this is not a game” convention that governs all ARGs, but since this something I and others here at the Institute aim to follow closely in the coming weeks and months, we’ll have to treat the curtain between fact and fiction as semi-transparent.

From the perspective of our research here, I’m deeply intrigued because the ARG is an entirely net-native storytelling genre, employing forms as diverse and scattered as the media landscape we live in today. ARGs don’t rely on a specific software application, game system or OS, rather they treat the entire Internet as their platform. Players typically employ a whole battery of information technologies — email, chat, blogs, search engines, message boards, wikis, social media sites, cell phones — in pursuit of an elusive narrative thread.

The story is usually spun through cryptic clues and half-disclosures, one bread crumb at a time, by the game’s authors, or “puppetmasters.” To have any hope of success, players must work together, sharing clues and pooling information as they go. The whole point is to make the story into a group obsession — to mobilize players into problem-solving collectives where they can debate and test different hypotheses as a smart mob. It’s sort of like surfing an alternate version of the net, using all the social search tactics of the real one.

Of course, the net is a murky territory, full of conspiracy theories, identity traps and misinformation. ARGs take this uncertainty and make it their idiom. The game (remember, it’s not a game) might involve websites that to the casual observer look perfectly real — a corporate home page, a personal blog — but that are in fact a part of the fiction. ARGs use the playbook of spammers, phishers and social reality hackers like the Yes Men to create a fictional universe that blends seamlessly with the real.

But we’re not just talking about an alternate net here, we’re talking about an alternative world. ARGs frequently assign tasks that pull players away from their computers and propel them into their physical environment (the phenomenally popular I Love Bees had people running all over San Francisco answering pay phones). This couldn’t be more unlike the whole Second Life phenomenon (which, as you may have noticed, we’ve barely covered here). Instead of building a one-to-one simulacrum of the actual world (yeah yeah, you can fly, big whoop), this takes the actual world and tilts it — reinterprets it. There’s imagination happening here.

World Without Oil takes this in a new direction. McGonigal has been talking for some time now about using ARGs for more than just pure play. She believes they could be harnessed to solve real world problems (for more about this, read this recent long piece in SF Weekly by Eliza Strickland). Hence the premise of oil shocks. The WWO website was set up by ten friends who met in the chaos of the Denver Airport during the blizzards this past December. During that time, they bonded and got to talking about citizen journalism and the potential of the web for organizing masses of people to deal with crises without having to rely solely on big media and big government. A weird tip about an impending oil crisis on April 30th got their paranoid wheels turning and they decided to set up a central hub for netizens to send reportage and personal testimonies about life during the shocks. Today is April 30 and lo and behold: the shocks have arrived!

The idea is to collectively imagine a reality that could very likely come to pass, and to share information and ideas — alternative energy innovations, new forms of transport, new forms of community — that could help us get through it. It’s an opportunity for self-reeducation and perhaps the forging of some real-world relationships. There’s even a page for teachers to guide students through this collaborative hallucination, and to learn something about energy geopolitics as they do it.

As an entry to the serious games movement, this has to be one of the most innovative efforts out there. But I find myself wondering whether simply getting everyone to report from their corner of the crisis — postcards from the apocalypse –will be enough to create a full-blown ARG phenomenon. Is this participatory in quite the right way? While I ecstatically applaud the intention here of repurposing a form that to date has been employed mainly as a viral marketing tool (the first ARG was built around Spielberg’s “A.I.” in 2001), I worry that the WWO construct seems to have been shorn of most of the usual mystery elements — the codes, clues and crumbs — that make ARGs so addictive. There’s a whiff of homework here, something perhaps a little too earnest, that could prevent it from gaining traction. I sincerely hope I’m wrong.

Still, even if this fails to take off, I think this is an important milestone and will be important to study as it unfolds. WWO suggests what could be the ideal dystopian form for the cultural moment: a mode of storytelling that taps directly into the present human condition of networked information blitz and tries to channel it toward real-world awareness, or even action. The ARG adopts tactics long employed in military war games and conflict exercises and turns them (at least potentially) toward grassroots activism. WWO is trying to rouse, as Sebastian Mary put it in a previous post, our “democratic imagination. In SF Weekly piece I link to above, McGonigal puts it this way:

“When you start projecting that out to bigger scales, that’s when these games start to look like a real way to achieve, if not world peace, then some kind of world-benevolent conspiracy, where we feel like we are all playing the same game.”

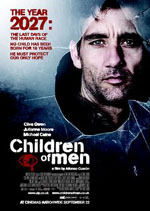

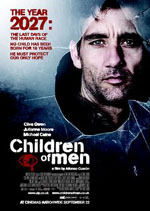

Many people I know loved the film “Children of Men” by Alfonso Cuarón because they felt that it showed them, with the cutting clarity of allegory, the way the world really is. The premise, that the human race has lost the ability to reproduce itself (a dying world, without children, slowly self-destructing), was of course implausible, but all the same it felt like a layer was being peeled away to reveal a terrible truth. Probably the most unsettling moment for me was the lights rose at the end and we exited the theater into the street. Everything looked different, fragile, like something awful was being hidden just beneath the surface. But the feeling soon faded and I filed the experience away: “Children of Men”; a brilliant film; one of the year’s best; shamefully overlooked at the Oscars.

Many people I know loved the film “Children of Men” by Alfonso Cuarón because they felt that it showed them, with the cutting clarity of allegory, the way the world really is. The premise, that the human race has lost the ability to reproduce itself (a dying world, without children, slowly self-destructing), was of course implausible, but all the same it felt like a layer was being peeled away to reveal a terrible truth. Probably the most unsettling moment for me was the lights rose at the end and we exited the theater into the street. Everything looked different, fragile, like something awful was being hidden just beneath the surface. But the feeling soon faded and I filed the experience away: “Children of Men”; a brilliant film; one of the year’s best; shamefully overlooked at the Oscars.

What would “Children of Men” look like as an ARG? What would a networked tactic bring to this story? Would it be simply dispatches from a dying world, or could we do something more constructive? Could the darkened theater and the streets outside somehow be merged?

Our first stories were oral stories. When we were children our parents read to us aloud stories that we listened to over and over again until they were embedded in our unconscious. We knew the stories inside and out, backwards and forwards. Reading became a ritual of call and response: a physical act. In the classroom too, teachers read aloud to us. We knew the stories inside and out, backwards and forwards. Call and response. At recess we ran out into the playground and re-eanacted the stories — replayed them, spun new ones. Those early experiences hearken back to earlier cultures — oral, pre-literate ones where the word was less the realm of contemplation and more the realm of action. ARGs seem to tap into this power of the oral story — the spark of the imagination and then the dash, together, into the playground.