Kim’s hypermedia poem cluster, “The Minotaur Project,” is currently featured at the Electronic Literature Organization. Highly recommended.

Category Archives: digital

introducing nexttext

The dawn of personal computing and the web has changed the way we learn, yet the tools of instruction have been sluggish to evolve. Nowhere is this more clear than with the printed textbook.

So the institute has launched nexttext, a project that seeks to accelerate the textbook’s evolution, onward from its current incarnation, the authoritative brick, toward something more fluid, more complete, and more alive – more fitting with this networked age.

Our aim is to encourage – through identifying existing experiments and facilitating new ones – the development of born-digital learning materials that will enhance, expand, and ultimately replace the printed textbook. To begin, we’ve set up a curated site showcasing the most significant digital learning experiments currently in the field. Our hunch is that by bringing these projects (and eventually, their creators) together in a single place, along with publishers and funders willing to take a risk, a concrete vision of the digital textbook for the near future might emerge. And actually happen.

So check out the site, comment, and by all means recommend other projects you think belong there. What’s up now is a seed group – things that have gotten our wheels turning so far – to be grown and expanded by the collective intelligence of the community.

thinking out loud

on sunday one of my colleagues, kim white, posted a short essay on if:book, Losing America, which eloquently stated her horror at realizing how far america has slipped from its oft-stated ideals of equality and justice. as kim said “I thought America (even under the current administration) had something to do with being civilized, humane and fair. I don’t anymore.”

kim ended her piece with a parenthetical statement:

(The above has nothing and everything to do with the future of the book.)

the four of us met around a table in the institute’s new williamsburg digs yesterday and discussed why we thought kim’s statement did or didn’t belong on if:book. the result — a resounding YES.

if you’ve been reading if:book for awhile you’ve probably encountered the phrase, “we use the word book to refer to the vehicle humans use to move big ideas around society.” of course many, if not most books are about entertainment or personal improvement, but still the most important social role of books (and their close dead-tree cousins, newspapers, magazines etc.) has been to enable a conversation across space and time about the crucial issues facing society.

we realize that for the institute to make a difference we need to be asking more the right questions.although our blog covers a wide-range of technical developments relating to the evolution of communication as it goes digital, we’ve tried hard not to be simple cheerleaders for gee-whiz technology. the acid-test is not whether something is “cool” but whether and in what ways it might change the human condition.

which is why kim’s post seems so pertinent. for us it was a wake-up call reinforcing our notion that what we do exists in a social, not a technological context. what good will it be if we come up with nifty new technology for communication if the context for the communication is increasingly divorced from a caring and just social contract. Kim’s post made us realize that we have been underemphasizing the social context of our work.

as we discuss the implications of all this, we’ll try as much as possible to make these discussions “public” and to invite everyone to think it through with us.

katrina and the interactive atlas

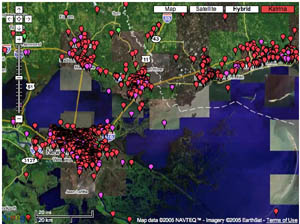

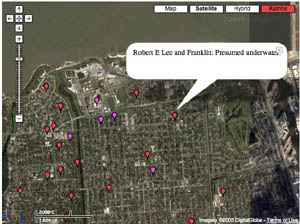

Interactive maps help those of us not in the region to grasp the terrain of devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina. These maps are suggestive of a new paradigm for the digital page – an interactive canvas, or territory, through which the reader can zoom through orders of magnitude.

Most talked about is the “visual wiki” at scipionus.com – a re-tooling of Google maps that invites users to post tabs with information pertaining to specific locales (as fine-grained as streetcorners). Tabs are editable and are supposed to be used only for concrete reports, though many have posted pleas for news of specific missing persons or of the condition of certain blocks. Some samples:

“Saw news video 9/2/05 of corner street sign at 10th St. & Pontchartrain Blvd. Water level was about 6 in. below. green street signs.”

“the Ashley’s are in Prattville AL”

“4400 Calumet — dry on Weds?”

“as of 5:00 pm.. the streets from wilson canal to transcontinental are COMPLETELY DRY! source from somebody who stayed and called to tell us the info.”

“Dylan Nash anyone?? call 919-7307018”

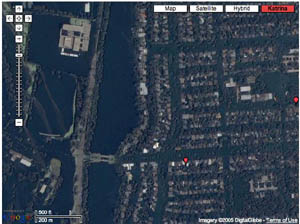

The maps include post-Katrina satellite imagery, which reveals, upon zooming in, horrifying grids of inundated streets, stadiums filled up like soup tureens, city parks transformed into swamps. Wired recently ran a piece about sciponius.

Before & After:

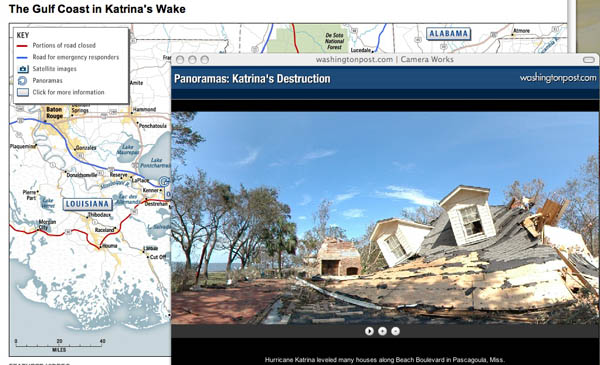

I was also impressed by the interactive maps on washingtonpost.com.

Click on spinning wheels at various points along the coastline and windows pop up with scrolling panoramic shots. Quite stunning. You can click the screen and drag the scroll in either direction, stop it, speed it up, and even pull it up and down to reveal glimpses of the sky or ground. Photojournalism is given new room to play on online newspapers.

(No Need to Click Here – I’m just claiming my feed at Feedster feedster:d50fedfc363272797584521a06a79da5)

the selected, annotated outbox of dave eggers

Email killed the practice of letter-writing so suddenly that we haven’t a chance to think about the consequences. The Times Book Review ran an essay this weekend on the problem this poses for literary historians, biographers and archivists, who long have relied on collected letters and papers to fill in the gaps between a writer’s published work. In the same review, the Times covers a new biography of the legendary critic Edmund Wilson largely based on his correspondences, and last week covered a new collection of the letters of poet James Wright. Letters are often treated as literature in themselves.

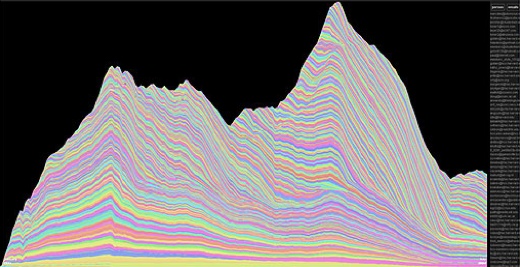

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

There isn’t necessarily anything less rich about email correspondence. It excels at capturing a vibrant volley of words with great immediacy, whereas paper letters permit deeper communiques, fewer and father between. But in some cases, these characterizations do not hold up. With reliable postal service, letters can fly back and forth quite rapidly. And just because an email suddenly appears in your box does not mean that it will be immediately read, let alone replied to. Sometimes we write long email letters, expecting that the receiver is busy and will take time to reply. These differences, true and false, are worth evaluating.

But if collected emails are to become a literary tool, there is no question that we will need more reliable ways of archiving and preserving digital correspondence. We will also need new editorial approaches for collecting and publishing them. A printed volume, or series of volumes, might be insufficient for presenting a massive 4 gigabyte email archive by Dave Eggers (No one wants to read the phone book from cover to cover). And according to the Times piece, Eggers’ agent Andrew Wylie is mulling over such a project. What would make more sense is an electronic edition that is essentially a selected or complete annotated Eggers Outbox, with folders and tags provided for categorization, a powerful search function, and the ability to organize according to your own interests. There would also be browsing and skimming tools that would allow a reader to move rapidly across vast tracts of correspondence and still find what they are looking for. And maybe, a way to email the author yourself and become a part of the living archive.

if:book one of five blogs for blogday

Writing and the Digital Life, a brand new weblog with interests very similar to ours, just went live today and has kindly named us among five blogs for “blogday.” I look forward to reading their site.

the light of the disk is endless

“The cover of the book was rubbed with a patina made from lamp black, Yakskin glue, and brains. It was burnished to a gloss and inscribed with an ink made from crushed pearls and silver.” That is a description of the one of the Tibetan monastic manuscripts, or pothi, that Jim Canary discussed in his recent presentation, “The Tibetan Book: From Pothi to Pixels and Back Again,” at The Changing Book Conference (University of Iowa). Pothi were originally made of palm leaves. They are up to four feet in length and thin in shape; consisting of loose leaves in cloth covers pressed between wooden boards. They are sometimes housed in wooden boxes that resemble child-sized coffins. The Tibetan pothi are stored in long, narrow pigeon holes built into the walls surrounding the chanting area of the temple. Jim showed us a picture of these impressive libraries, with ceilings so high, the walls, and their overstuffed catacombs, disappear into darkness.

Jim Canary has over sixty of hours of video, taken during his trips to Tibet, documenting the monastic printing process. He plans to edit and publish the video as a CD Rom in tandem with a print book. He showed us some selections, which I do not have, so I will do my best to describe them. Video #1: a man sits on the stone steps outside the temple. There are two tall stacks of paper next to him and a bowl of water in front of him. He is preparing the paper for printing, taking one sheet from the top of the pile, passing it through a pan of water and placing it on top of the other pile. He has hundreds of sheets to dampen, so he is working in a brisk rhythmic manner. When he’s finished, the stack will be pressed between two wooden blocks. Video #2: printing takes place in a building across from the temple. The printing is done in teams of two. One man holds the hand-carved wooden block and prepares it with ink. His partner places each damp sheet on the wooden block for burnishing, then removes it and sets it aside to dry. The men work quickly in tandem, surrounded by the music of monks chanting in the temple next door. The tone and rhythm of the chant matches the rhythm of their work. It is designed to correspond with the heart beat, and it works to knit all participants together into a single, metaphorical “body” which is, in turn, joined to all humanity through the meditation. The result of all this unity is a book, shaped like a body, which will be housed, along with hundreds of others, in the temple walls.

Mr. Canary’s presentation was also about the future of these mystical books, which are being cataloged, preserved, reproduced and distributed using digital technology. Some monks are now working on laptops, transcribing text and burning DVDs. Here is an excerpt from a poem written by one of the monks in praise of digital materials, which, in his eyes, are as exquiste as a patina made from lamp black, Yakskin glue, and brains, burnished to a gloss and inscribed with an ink made from crushed pearls and silver are to me.

…The light of the disk is endless

like the light of the disks in the sky, sun and moon.

With a single push of our finger on a button

We pull up the shining gems of text…

-Gelek Rinpoche

The 2005 Computers and Writing Conference

Stanford University hosted the 2005 Computers and Writing conference this past weekend. Each session was rife with “future of the book” food for thought. This is an informal summary, with apologies to all the fabulous presentations that I don’t mention (sorry, being only one person, I could not attend them all). Some of the major themes (which dovetail nicely with issues we are exploring at the institute) included: Open Source, new interpretations of literacy and “writing,” the changing role of the teacher/student, performance, multimodality, and networked community. It is important to note that these themes often blur together in a complicated interdependence. This thematic interplay was evident in the pre-conference workshops which included instruction in open source tools and applications like Drupal that allow for multimodality and the creation of communal authoring environments. Workshops in “Reading Images” and “Using Video to Teach Writing” addressed multiple modalities and new concepts of writing.

I was excited to see that the Computers and Writing community understands the potential of, and imperative for, Open Source. It’s practical advantages (free and customizable) and it’s philosophical advantages (community-based and built for sharing rather than for selling) make it ideally suited to the goals of the educational community. Open Source came up over and over during the presentations and was featured in the first town hall session “Open Source Opens Thinking.” The session challenged the Computers and Writing community “to consider a position statement of collective principles and goals in relation to Open Source.” Such a statement would be useful and productive; I’m hoping it will materialize.

The changing role of the teacher and student was evident in several presentations: most notably, the pilot program at Penn State (see my earlier post) in which students publish their “papers” on a wiki. The wiki format allows for intensive peer-review and encourages a culture of responsibility.

There was a lot of speculation about how writing will evolve and how other modalities might be incorporated into our notion of literacy. Andrea Lunsford‘s keynote speech addressed this issue, calling for a return to oral and embodied “performative literacies.” She referred to Tara Shankar’s MIT dissertation “Speaking on the Record,” which confronts the way we privilege writing above other modalitites for knowledge and education. She says: “Reading and writing have become the predominant way of acquiring and expressing intellect in Western culture. Somewhere along the way, the ability to write has become completely identified with intellectual power, creating a graphocentric myopia concerning the very nature and transfer of knowledge. One of the effects of graphocentrism is a conflation of concepts proper to knowledge in general with concepts specific to written expression.”

Shankar calls for new practices that embrace oral communication. She introduces a new word: “to provide a counterpart to writing in a spoken modality: speak + write = sprite. Spriting in its general form is the activity of speaking “on the record” that yields a technologically supported representation of oral speech with essential properties of writing such as permanence of record, possibilities of editing, indexing, and scanning, but without the difficult transition to a deeply different form of representation such as writing itself.”

The need for a multimodal approach to writing was addressed in the second Town Hall meeting “Composition Beyond Words.” Virginia Kuhn opened by calling for a reconsideration of “writing,” and the goals of visual literacy. Bradley Dilger reminded us that literacy goes beyond “the letter;” we need multiple interfaces for the same data because not everyone looks at data the same way. Madeleine Sorapure pointed out that writing with computers is determined by underlying code structures which are, themselves, a form of writing. She quoted Loss Pequeno Glazier, “Code is the writing within the writing that makes the work happen.” Gail Hawisher, talked about the 10 year process of incorporating multiple modalities into the first-composition courses at the University of Illinois. Cynthia Selfe addressed this struggle, saying: “colleges are not comfortable with multiple modalities.” She advises the C&W community to “think about how to give professional development/support to resistant colleges in ways that are sustainable over time.” Stuart Moulthrop also offered some cautionary words of advice. In addition to faculty and administration, Moultrop says students are resistant to multimodality. Code, for example, is fatally hard to teach non-programmers or visually oriented people. “There is a political problem,” Moulthrop says, “we are living through a backlash moment. People are very angry about how fast the future has come down on them.”

Some participants delivered “papers” that attempted to demonstrate these new multimodal imperatives. Most notably, Todd Taylor‘s presentation, “The End of Composition,” which asked, “Can a paper be a film?” Todd argues “yes” with a cinematic montage of sampled and remixed clips along with original footage, which was enthusiastically received by the audience (alt. review in Machina Memorialis blog.) Morgan Gresham‘s Town Hall presentation was a student-produced video and a question to the audience; is this just a remake of a bad commercial, or is it a “paper”? Christine Alfano‘s presentation experimented with a hypertext, “Choose Your Own Adventure,” style that allowed the audience to determine the trajectory of the talk. Once the selection was made, she dropped the other two papers/options to the floor. The choice, unfortunately for me, eliminated the material that I most wanted to hear about (Shelly Jackson’s Patchwork Girl). Additionally, “virtual” presentations were delivered during an online companion conference called: Computers and Writing Online 2005 When Content Is No Longer King: Social Networking, Community, and Collaboration This interactive online conference served, “as an acknowledgment of the value of social networks in creating discourse of and about scholarly work.” CWOnline 2005 made both the submission and presentation process open to public review via the Kairosnews weblog. Despite some flaws, I thought these experimental presentations pushed at the boundaries of academic discourse in a useful way. They reminded us how far we have to go and how difficult the project of putting ideas into practice really is.

Finally, the conference highlighted ways in which computers are being used to cultivate community across cultures and institutions; and between students, teachers, and scholars. Sharing Cultures, a joint project of Columbia College Chicago and Nelson Mandela University Metropolitan University, in South Africa “creates two interconnected, on-line writing and learning communities…the project purposely includes students who traditionally have not had access to, or have been actively marginalized from, both digital and international experiences.” Virginia Kuhn approached computers and community at the local level, with a service learning class called, “Multicultural America,” which asked students to write an ebook documenting local history. The finished work is part of an ongoing display at a Milwaukee community center. This project inspired an interesting reversal; community members who worked with students on the project are now (thanks to a generous grant) coming to the University of Milwaukee for supplemental study. Within the academy there are also exciting opportunities for computer-based community-building. In her Town Hall presentation, Gail Hawisher said that literacy on campus is, “usually taken care of by first year composition.” If we are to incorporate visual literacy into our definition of literacy then, “Perhaps we should be looking to art and design for literacy instead of just the English dept.” This is an incredibly smart idea because, short of requiring composition teachers to have degrees in art, film, AND writing, collaborative efforts with other departments seem to be the best way to ensure a deep and rigorous understanding of the material. I had an interesting conversation with Stuart Moulthrop about this. We imagined a massively-multi-player game environment that would allow scholars from around world to collaborate on curriculum across institutional and disciplinary boundaries. Wouldn’t it be great, we thought, if someone who wanted to teach an odd combination like, film/biology/physics, could put a course scenario into the game where it would be played out by biologists, film scholars, and physicists. In other words a kind of life-time learning environment for the experts, a laboratory for the exchange of knowledge across disciplinary boundaries, and place to weave together different strands of human insight in order to create a more complete “picture” of the universe.