I’m in Milan for the ifbookthen conference. Corriere della Serra (the leading Italian newspaper) asked me for an opinion piece they could publish in La Lettura, their weekly magazine, on the occasion of the meeting. This is what I gave them.

The Future of the Book

As someone who made the leap from print to electronic publishing over thirty years ago people often ask me to expound on the “future of the book.” Frankly, I can’t stand the question, especially when asked simplistically. For starters it needs more specificity. Are we talking 2 years, 10 years or 100 years? And what does the questioner mean by “book” anyway? Are they asking about the evolution of the physical object or its role in the social fabric?

It’s a long story but over the past thirty years my definition of “book” has undergone a major shift. At the beginning I simply defined a book in terms of its physical nature — paper pages infused with ink, bound into what we know as the codex. But then in the late 1970s with the advent of new media technologies we began to see the possibility of extending the notion of the page to include audio and video, imagining books with audio and video components. To make this work conceptually, we started defining books not in terms of their physical components but how they are used. From this perspective a book isn’t ink on bound paper, but rather “a user-driven medium” where the reader is in complete control of how they access the contents. With laser videodiscs and then cd-roms users/readers started “reading” motion pictures; transforming the traditionally producer-driven experience where the user simply sat in a chair with no control of pace or sequence into a fully user-driven medium.

This definition worked up through the era of the laser videodisc and the cd-rom, but completely fell apart with the rise of the internet. Without an “object” to tie it to, I started to talk about a book as the vehicle humans use to move ideas around time and space.

People often expressed opposition to my freewheeling license with definitions but I learned to push back, explaining that it may take decades, maybe even a century for stable new modes of expression and the words to describe them to emerge. For now I argued, it’s better to continuously redefine the definition of “book” until something else clearly takes its place.

A Book is a Place

In 2005 when the U.S. based Macarthur Foundation gave me a huge grant to explore how publishing might evolve as it moves from the printed page to the networked screen I used the money to found what I playfully named The Institute for the Future of the Book. With a group of young people, just out of university and coming of age in the era of the social web, we carried out a number of experiments under the rubric of “networked books.”

This was the moment of the blog and we wondered what would happen if we applied the concept of “reader comments” to essays and books. Our first attempt, McKenzie Wark’s Gamer Theory, turned out to be a remarkably lucky choice. The book’s structure — numbered paragraphs rather than numbered pages — required my colleagues to come up with an innovative design allowing readers to make comments at the level of the paragraph rather than the page. Their solution to what at the time seemed like a simple graphical UI problem, was to put the comments to the right of each of Wark’s paragraphs rather than follow the standard practice of placing them underneath the author’s text.

Within a few hours of putting Gamer Theory online, a vibrant discussion emerged in the margins. We realized that moving comments from the bottom to the side, a change that at the time seemed minor, in fact had profound implications. Largely because Wark took a very active role in the unfolding discussion, our understanding at first focused on the ways in which this new format upends the traditional hierarchies of print which place the author on a pedestal and the reader at her adoring feet. With the side-by-side layout of Gamer Theory‘s text and comments, author and reader were suddenly occupying the same visual space; which in turn shifted their relationship to one of much greater equality. As the days went by it became clear that author and reader were engaged in a collaborative effort to increase their collective understanding.

We started to talk about “a book as a place” where people congregate to hash out their thoughts and ideas.

Later experiments in classrooms and reading groups were just as successful eventhough no author was involved, leading us to realize we were witnessing much more than a shift in the relationship between author and reader.

The reification of ideas into printed, persistent objects obscures the social aspect of both reading and writing, so much so, that our culture portrays them as among the most solitary of behaviors. This is because the social aspect traditionally takes place outside the pages — around the water cooler, at the dinner table and on the pages of other publications in the form of reviews or references and bibliographies. In that light, moving texts from page to screen doesn’t make them social so much as it allows the social components to come forward and to multiply in value.

And once you’ve engaged in a social reading experience the value is obvious. Contemporary problems are sufficiently complex that individuals can rarely understand them on their own. More eyes, more minds collaborating on the task of understanding will yield better, more comprehensive answers.

Our grandchildren will assume that reading with others, i.e. social reading, is the “natural” way to read. They will be amazed to realize that in our day reading was something one did alone. Reading by one’s self will seem as antiquated as silent movies are to us.

The difficult thing however about predicting the future of reading is that everything i’ve said so far presumes that what is being read is an “n-page” article or essay or an “n-page,” “n-chapter” book,” when realistically, the forms of expression will change dramatically as we learn to exploit the unique affordances of new electronic media. Ideally, the boundaries between reading and writing will become ever more porous as readers take a more active role in the production of knowledge and ideas.

Clemens Setz, the author of the literary novel Indigo watched the conversation unfold as 40 students in a class at Hildesheim University outside Berlin carried out an extensive conversation with over 1800 comments. At a recent symposium Setz said that knowing his readers would be playing an active role in the margin will effect how he writes; he’ll make room for their participation.

Follow the Gamers

And lest, you think this shift applies only to non-fiction, please consider huge multi-player games such as World of Warcraft as a strand of future-fiction where the author describes a world and the players/readers write the narrative as they play the game.

Although we date the “age of print” from 1454, more than two hundred years passed before the “novel” emerged as a recognizable form. Newspapers and magazines took even longer to arrive on the scene. Just as Gutenberg and his fellow printers started by reproducing illustrated manuscripts, contemporary publishers have been moving their printed texts to electronic screens. This shift will bring valuable benefits (searchable text, personal portable libraries, access via internet download, etc.), but this phase in the history of publishing will be transitional. Over time new media technologies will give rise to new forms of expression yet to be invented that will come to dominate the media landscape in decades and centuries to come.

My instinct is that game makers, who, unlike publishers, have no legacy product to hold them, back will be at the forefront of this transformation. Multimedia is already their language, and game-makers are making brilliant advances in the building of thriving, million-player communities. As conventional publishers prayerfully port their print to tablets, game-makers will embrace the immense promise of networked devices and both invent and define the dominant modes of expression for centuries to come.

The Future of the Book is the Future of Society

“The medium, or process, of our time — electric technology — is reshaping and restructuring patterns of social interdependence and every aspect of our personal life.

It is forcing us to reconsider and re-evaluate practically every thought, every action, and every institution formerly taken for granted. Everything is changing: you, your family, your education, your neighborhood, your job, your government, your relation to “the others. And they’re changing dramatically.” Marshall McLuhan, The Medium is the Message

Following McLuhan and his mentor Harold Innis, a persuasive case can be made that print played the key role in the rise of the nation state and capitalism, and also in the development of our notions of privacy and the primary focus on the individual over the collective. Social reading experiments and massive multi-player games are baby steps in the shift to a networked culture. Over the course of the next two or three centuries new modes of communication will usher in new ways of organizing society, completely changing our understanding of what it means to be human.

Category Archives: culture

books and the man i sing

I’ve been reading failed Web1.0 entrepreneur Andrew Keen’s The Cult of the Amateur. For those who haven’t hurled it out of the window already, this is a vitriolic denouncement of the ways in which Web2.0 technology is supplanting ‘expert’ cultural agents with poor-quality ‘amateur’ content, and how this is destroying our culture.

In vehemence (if, perhaps, not in eloquence), Keen’s philippic reminded me of Alexander Pope (1688-1744). Pope was one of the first writers to popularize the notion of a ‘critic’ – and also, significantly, one of the first to make an independent living through sales of his own copyrighted works. There are some intriguing similarities in their complaints.

In the Dunciad Variorum (1738), a lengthy poem responding to the recent print boom with parodies of poor writers, information overload and a babble of voices (sound familiar, anyone?) Pope writes of ‘Martinus Scriblerus’, the supposed author of the work

He lived in those days, when (after providence had permitted the Invention of Printing as a scourge for the Sins of the learned) Paper also became so cheap, and printers so numerous, that a deluge of authors cover’d the land: Whereby not only the peace of the honest unwriting subject was daily molested, but unmerciful demands were made of his applause, yea of his money, by such as would neither earn the one, or deserve the other.

The shattered ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’, lamented by Pope in the eighteenth century when faced with a boom in printed words, is echoed by Keen when he complains that “the Web2.0 gives us is an infinitely fragmented culture in which we are hopelessly lost as to how to focus our attention and spend our limited time.” Bemoaning our gullibility, Keen wants us to return to an imagined prelapsarian state in which we dutifully consume work that has been as “professionally selected, edited and published”.

In Keen’s ideal, this selection, editing and publication ought (one presumes) to left in the hands of ‘proper’ critics – whose aesthetic in many ways still owes much to (to name but a few) Pope’s Essay On Criticism (1711), or the satirical work The Art of Sinking In Poetry (1727). But faith in these critics is collapsing. Instead, new tools that enable books to be linked give us “a hypertextual confusion of unedited, unreadable rubbish”, while publish-on-demand services swamp us in “a tidal wave of amateurish work”.

So what? you might ask. So the first explosion in the volume of published text created some of the same anxieties as this current one. But this isn’t a narrative of relentless evolutionary progress towards a utopia where everything is written, linked and searchable. The two events don’t exist on a linear trajectory; the links between Pope’s critical writings and Keen’s Canute-like protest against Web2.0 are more complex than that.

Pope’s response to the print boom was not simply to wish things could return to their previous state; rather, he popularized a critical vocabulary that both helped others to deal with it, and also – conveniently – positioned himself at the tip of the writerly hierarchy. His extensive critical writings, promoting the notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ quality writing and lambasting the less talented, served to position Pope himself as an expert. It is no coincidence that he was one of the first writers to break free of the literary patronage model and make a living out of selling his published works. The print boom that he critiqued so scatologically was the same boom that helped him to the economic independence that enabled him to criticize as he saw fit.

But where Pope’s approach to the print boom was critical engagement, Keen offers only nostalgic blustering. Where Pope was crucial in developing a language with which to deal with the print boom, Keen wishes only to preserve Pope’s approach. So, while you can choose to read the two voices, some three centuries apart, as part of a linear evolution, it’s also possible to see them as bookends (ahem) to the beginning and end of a literary era.

This era is characterized by a conceptual and practical nexus that shackles together copyright, authorship and a homogenized discourse (or ‘common high culture’, as Keen has it), delivers it through top-down and semi-monopolistic channels, and proposes always a hierarchy therein whilst tending ever more towards proliferating mass culture. In this ecology, copyright, elitism and mass populism form inseparable aspects of the same activity: publications and, by extension, writers, all busy ‘molesting’ the ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’ with competing demands on ‘his applause, yea [on] his money’.

The grading of writing by quality – the invention of a ‘high culture’ not merely determined by whichever ruler chose to praise a piece – is inextricable from the birth of the literary marketplace, new opportunities as a writer to turn oneself into a brand. In a word, the notion of ‘high culture’ is intimately bound up in the until-recently-uncontested economics of survival as a writer.

Again, so what? Well, if Keen is right and the new Web2.0 is undermining ‘high culture’, it is interesting to speculate whether this is the case because it is undermining writers’ established business model, or whether the business model is suffering because the ‘high’ concept is tottering. Either way, if Keen should be lambasted for anything it is not his puerile prose style, or for taking a stand against the often queasy techno-utopianism of some of Web2.0’s champions, but because he has, to date, demonstrated little of Pope’s nous in positioning himself to take advantage of the new economics of publishing.

Others have been more wily, though, in working out exactly what these economics might be. While researching this piece, I emailed Chris Anderson, Wired editor, Long Tail author, sometime sparring partner for Keen and vocal proponent of new, post-digital business models for writers. He told me that

“For what I do speaking is about 10x more lucrative than selling books […]. For me, it would make sense to give away the book to market my personal appearances, much as bands give away their music on MySpace to market their concerts. Thus the title of my next book, FREE, which we will try to give away in every way possible.”

Thus, for Anderson, there is life beyond copyright. It just doesn’t work the same way. And while Keen claims that Web2.0 is turning us into “a nation so digitally fragmented it’s no longer capable of informed debate” – or, in other words, that we have abandoned shared discourse and the respected authorities that arbitrate it in favor of a mulch of cultural white noise, it’s worth noting that Anderson is an example of an authority that has emerged from within this white noise. And who is making a decent living as such.

Anderson did acknowledge, though, that this might not apply to every kind of writer – “it’s just that my particular speaking niche is much in demand these days”. Anderson’s approach is all very well for ‘Big Ideas’ writers; but what, one wonders, is a poet supposed to do? A playwright? My previous post gives an example of just such a writer, though Doctorow’s podcast touches only briefly on the economics of fiction in a free-distribution model. I’ve argued elsewhere that ‘fiction’ is a complex concept and severely in need of a rethink in the context of the Web; my hunch is that while for nonfiction writers the Web requires an adjustment of distribution channels and little more, or creative work – stories – the implications are much more drastic.

I have this suspicion that, for poets and storytellers, the price of leaving copyright behind is that ‘high art’ goes with it. And, further, that perhaps that’s not as terrible as the Keens of this world might think. But that’s another article.

net-native stories are already here: so are the vultures

A split is under way in the culture industry at present, between ever more high-budget centrally-created and released products designed to net the ‘live experience’ ticket or product-buying punter, and new forms of distributed, Net-mediated creativity. This is evidenced throughout the culture industry; but while ARGs (alternate reality games) are a strong candidate for being understood as the ‘literary’ output of this new culture, there is little discussion of increasing attempts to transform this emerging genre straight into a vehicle for advertising. In the light of my own rather old-fashioned literary idealism, I want first to situate ARGs in the context of this split between culture-as-industry and culture-as-community, to argue the case for ARGs as participatory literature, and finally to ponder the appropriateness of leaving them to the mercies of the PR industry.

the culture industry and the new collaboration

Anti-pirating adverts have been common since video came into wide use. But the other day I saw one at the cinema that got me thinking. Rather than taking the line that copying media is a crime, it showed scenes from Apocalypto, while pointing out that such a spectacular film is much better enjoyed on a huge cinema screen. It struck me as a shrewd take: rather than making ominous noises about crime, the advert aimed to drive cinema attendance by foregrounding the format-specific benefits (darkened room, audience, popcorn, huge screen) of the cinema experience .

It reminded me of a conversation I had with musician-turned-intellectual Pat Kane. Since the advent of iTunes and the like, he said, gigging is often a musician’s main source of income. I had a look at live performance prices, and discovered that whereas in 2001 high-end tickets cost $60, in 2006 Paul McCartney (amongst others) charged $250 per ticket. The premium is for the format-specific features of the experience: the atmosphere, the ‘authenticity’, the transient moment. Everything else is downloadable.

But the catch is that you have to sell material that suits the ‘live’ immersive experience. That means all-singing, all-dancing extravaganza gigs (Madonna crucified on a mirrored cross in Rome, anyone?) and super-colossal epic ‘excitement’ films, full of special effects, chases, explosions and the like. Consider the top ten grossing films 2000-06: three Harry Potters, three Lord of the Ringses, three X-Men films, three Star Warses, three Matrix films, Spider-man, two Batmans, The Chronicles of Narnia, Day After Tomorrow, Jurassic Park 3, Terminator 3 and War of the Worlds. Alongside that there were typically at least two high-budget CGI films in the top ten each year Exciting fantasy epics are on the up, because if you produce anything else the punters are more likely to skip the cinema experience and just download it.

So the networked replicability of content drives a trend for high-budget, high-concept cultural content for which you can justifiably charge at the door. But other forms are on the up. The NYT just ran a story about M dot Strange, who brought a huge YouTube audience to his Sundance premiere. And December’s Wired called the LonelyGirl15 phenomenon on YouTube ‘The future of TV’. It’s not as if general cinema release is the only way to make your name. Sandi Thom‘s rise to fame through a series of webcasts tells the same story.

Here, we see artists who reverse the paradigm: rather than seeking to thrill a passive audience, they intrigue an active one. Rather than seeking to retain control, they farm parts of the story out. As Lonelygirl15’s story grows, each characer will get a vlog: rather than produce the whole thing themselves, the originators will work out a basic storyline and then pair writers and directors with actors and let them loose.

I don’t wish to argue here that this second paradigm of community-based participative creation is necessarily ‘better’, or that it will supplant existing cultural forms. But it is emerging rapidly as a major cultural force, and merits examination both in its own right and for clues to the operation of Net-native forms of literature.

fact or fiction? who cares?

A frequent characteristic of these kinds of networked co-creation is debate about the ‘reality’ of its products. LonelyGirl15 whipped up a storm on ARG Network while people tried to work out if she was an ARG trailhead, an advertising campaign, or a real teenager. Similarly, many have suspected Sandi Thom’s webcast story of including a layer of fiction. But this has not hurt Sandi’s career any more than it killed interest in LonelyGirl15. Built into these discussions is a sense that this (like much ambiguity) is not a bug but a feature, and is actually intrinsic to the operation of the net. After all, the promise underpinning Second Life, MUDs, messageboards and much of the Net’s traffic is radical self-reinvention beyond the bounds of one’s life and physical body. Fiction is part of Net reality.

Literary theorists have held fiction in special regard for thousands of years; if fiction is intrinsic to the ‘reality’ of the Net, what happens to storytellers? Is there a kind of literature native to the Net?

ARGs: net-native literature

Though it’s a relatively young phenomenon, and I have no doubt that other forms will emerge, the strongest candidates at present for consideration as such are ARGs (alternate reality games). Unlike PVP online games, they are at least partially written (textual), and rely heavily on participants’ collaboration through messageboards. If you’re trying to catch up, you essentially read the ‘story’ as it is ‘written’ by its participants in fora dedicated to solving them. They have a clear story, but are dependent for their unfolding on community participation – and may be changed by this participation: in 2001, Lockjaw ended prematurely when participants brought a class-action lawsuit against the fictional genetic engineering company at the heart of the story. Or perhaps it didnt – I’ve seen one reference to this event, but other attempts simply lead me deeper into a story that may or may not still be active.

Thus, like LonelyGirl15 and her ilk, ARGs also bridge fact and fiction. This is part of their pleasure, and it is pervasive: I had a Skype conversation yesterday with Ansuman Biswas, an artist who has been sucked into the now-unfolding MEIGEIST game when its creators referenced his work in the course of casting story clues. Ansuman delightedly sent me the link to the initial thread on the game at unfiction, where participants have been debating whether Ansuman exists or not. Even though I was talking to him at the time I almost found myself wondering, too.

Where ARGs as a creative form diverge from print literature (at least, from modern print literature) is in their use of pastiche, patchwork and mash-up. One of the delights of storytelling is the sense of an organising intelligence at work in a chaos of otherwise random events. ARGs provide this, but in a way appropriate to the Babel of content available on the Net. Participants know that someone is orchestrating a storyline, but that it will not unfold without the active contribution of the decoders, web-surfers, inveterate Googlers and avid readers tracking leads, clues, possible hints and unfolding events through the chaos of the Web. Rather than striving for that uber-modernist concept, ‘originality’, an ARG is predicated on the pre-existence of the rest of the Net, and works like a DJ with the content already present. In this, it has more in common with the magpie techniques of Montaigne (1533-92), or the copious ‘authoritative’ quotations of Chaucer than contemporary notions of the author-as-originator.

the PR money-shot

The downside of some ARG activity is the rapid incursions of the marketing machine into the format, and a corresponding tendency towards high-budget games with a PR money-shot. For example, I Love Bees turned out to be a trailer for Halo 2. This spills over into offline publication: Cathy’s Book, itself an interactive multimedia concept co-written by Sean Stewart, one of the puppetmasters of the 2001 ARG ‘The Beast, made headlines last year when it included product placements from Clinique. So where YouTube, myspace, webcasts and the like appear to be working in some ways to open up and democratise creative activity as a community activity, it is as yet unclear whether the same is true of ARGs. Is it acceptable for immersive fiction to be so seamlessly integrated with the needs of the advertising world? Is the idealism of Aristotle and Sidney still worth keeping? Or is such purism obsolete?

where are the artists?

Either way, this new genre represents, I believe, the first stirrings of a Net-native form of storytelling. ARGs have all the characteristics of networked cultural production: they unfold through the collaboration of a networked problem-solving community; they use multiple media, mixtures of fact and fiction, and a distributed reader/participant base. Their operation, and their susceptibility to co-opting by the marketing industry poses many questions; but the very nature of the form suggests that the way to address these is through engagement, not criticism. So, ultimately, this is a call for writers and artists interested in what the form is and could become: to situate Net writing in the context of why writers have always written, to explore its potential, and to ensure that it remains a form that belongs to us, rather than being sold back to us in darkened theatres with a bagful of memorabilia.

transmitting live from cambridge: wikimania 2006

I’m at the Wikimania 2006 conference at Harvard Law School, from where I’ll be posting over the course of the three-day conference (schedule). The big news so far (as has already been reported in a number of blogs) came from this morning’s plenary address by Jimmy Wales, when he announced that Wikipedia content was going to be included in the Hundred Dollar Laptop. Exactly what “Wikipedia content” means isn’t clear to me at the moment – Wikipedia content that’s not on a network loses a great deal of its power – but I’m sure details will filter out soon.

I’m at the Wikimania 2006 conference at Harvard Law School, from where I’ll be posting over the course of the three-day conference (schedule). The big news so far (as has already been reported in a number of blogs) came from this morning’s plenary address by Jimmy Wales, when he announced that Wikipedia content was going to be included in the Hundred Dollar Laptop. Exactly what “Wikipedia content” means isn’t clear to me at the moment – Wikipedia content that’s not on a network loses a great deal of its power – but I’m sure details will filter out soon.

This move is obvious enough, perhaps, but there are interesting ramifications of this. Some of these were brought out during the audience question period during the next panel that I attended, in which Alex Halavis talked about issues of evaluating Wikipedia’s topical coverage, and Jim Giles, the writer of the Nature study comparing the Wikipedia & the Encyclopædia Britannica. The subtext of both was the problem of authority and how it’s perceived. We measure the Wikipedia against five hundred years of English-language print culture, which the Encyclopædia Britannica represents to many. What happens when the Wikipedia is set loose in a culture that has no print or literary tradition? The Wikipedia might assume immense cultural importance. The obvious point of comparison is the Bible. One of the major forces behind creating Unicode – and fonts to support the languages used in the developing world – is SIL, founded with the aim of printing the Bible in every language on Earth. It will be interesting to see if Wikipedia gets as far.

a2k wrap-up

—Jack Balkin, from opening plenary

I’m back from the A2K conference. The conference focused on intellectual property regimes and international development issues associated with access to medical, health, science, and technology information. Many of the plenary panels dealt specifically with the international IP regime, currently enshrined in several treaties: WIPO, TRIPS, Berne Convention, (and a few more. More from Ray on those). But many others, instead of relying on the language in the treaties, focused developing new language for advocacy, based on human rights: access to knowledge as an issue of justice and human dignity, not just an issue of intellectual property or infrastructure. The Institute is an advocate of open access, transparency, and sharing, so we have the same mentality as most of the participants, even if we choose to assail the status quo from a grassroots level, rather than the high halls of policy. Most of the discussions and presentations about international IP law were generally outside of the scope of our work, but many of the smaller panels dealt with issues that, for me, illuminated our work in a new light.

In the Peer Production and Education panel, two organizations caught my attention: Taking IT Global and the International Institute for Communication and Development (IICD). Taking IT Global is an international youth community site, notable for its success with cross-cultural projects, and for the fact that it has been translated into seven languages—by volunteers. The IICD trains trainers in Africa. These trainers then go on to help others learn the technological skills necessary to obtain basic information and to empower them to participate in creating information to share.

—Ronaldo Lemos

The ideology of empowerment ran thick in the plenary panels. Ronaldo Lemos, in the Political Economy of A2K, dropped a few figures that showed just how powerful communities outside the scope and target of traditional development can be. He talked about communities at the edge, peripheries, that are using technology to transform cultural production. He dropped a few figures that staggered the crowd: last year Hollywood produced 611 films. But Nigeria, a country with only ONE movie theater (in the whole nation!) released 1200 films. To answer the question of how? No copyright law, inexpensive technology, and low budgets (to say the least). He also mentioned the music industry in Brazil, where cultural production through mainstream corporations is about 52 CDs of Brazilian artists in all genres. In the favelas they are releasing about 400 albums a year. It’s cheaper, and it’s what they want to hear (mostly baile funk).

We also heard the empowerment theme and A2K as “a demand of justice” from Jack Balkin, Yochai Benkler, Nagla Rizk, from Egypt, and from John Howkins, who framed the A2K movement as primarily an issue of freedom to be creative.

The panel on Wireless ICT’s (and the accompanying wiki page) made it abundantly obvious that access isn’t only abut IP law and treaties: it’s also about physical access, computing capacity, and training. This was a continuation of the Network Neutrality panel, and carried through later with a rousing presentation by Onno W. Purbo, on how he has been teaching people to “steal” the last mile infrastructure from the frequencies in the air.

Finally, I went to the Role of Libraries in A2K panel. The panelists spoke on several different topics which were familiar territory for us at the Institute: the role of commercialized information intermediaries (Google, Amazon), fair use exemptions for digital media (including video and audio), the need for Open Access (we only have 15% of peer-reviewed journals available openly), ways to advocate for increased access, better archiving, and enabling A2K in developing countries through libraries.

—The Adelphi Charter

The name of the movement, Access to Knowledge, was chosen because, at the highest levels of international politics, it was the one phrase that everyone supported and no one opposed. It is an undeniable umbrella movement, under which different channels of activism, across multiple disciplines, can marshal their strength. The panelists raised important issues about development and capacity, but with a focus on human rights, justice, and dignity through participation. It was challenging, but reinvigorating, to hear some of our own rhetoric at the Institute repeated in the context of this much larger movement. We at the Institute are concerned with the uses of technology whether that is in the US or internationally, and we’ll continue, in our own way, to embrace development with the goal of creating a future where technology serves to enable human dignity, creativity, and participation.

cultural environmentalism symposium at stanford

Ten years ago, the web just a screaming infant in its cradle, Duke law scholar James Boyle proposed “cultural environmentalism” as an overarching metaphor, modeled on the successes of the green movement, that might raise awareness of the need for a balanced and just intellectual property regime for the information age. A decade on, I think it’s safe to say that a movement did emerge (at least on the digital front), drawing on prior efforts like the General Public License for software and giving birth to a range of public interest groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Creative Commons. More recently, new threats to cultural freedom and innovation have been identified in the lobbying by internet service providers for greater control of network infrastructure. Where do we go from here? Last month, writing in the Financial Times, Boyle looked back at the genesis of his idea:

We were writing the ground rules of the information age, rules that had dramatic effects on speech, innovation, science and culture, and no one – except the affected industries – was paying attention.

My analogy was to the environmental movement which had quite brilliantly made visible the effects of social decisions on ecology, bringing democratic and scholarly scrutiny to a set of issues that until then had been handled by a few insiders with little oversight or evidence. We needed an environmentalism of the mind, a politics of the information age.

Might the idea of conservation — of water, air, forests and wild spaces — be applied to culture? To the public domain? To the millions of “orphan” works that are in copyright but out of print, or with no contactable creator? Might the internet itself be considered a kind of reserve (one that must be kept neutral) — a place where cultural wildlife are free to live, toil, fight and ride upon the backs of one another? What are the dangers and fallacies contained in this metaphor?

Ray and I have just set up shop at a fascinating two-day symposium — Cultural Environmentalism at 10 — hosted at Stanford Law School by Boyle and Lawrence Lessig where leading intellectual property thinkers have converged to celebrate Boyle’s contributions and to collectively assess the opportunities and potential pitfalls of his metaphor. Impressions and notes soon to follow.

travel blindness

I went to Paris last weekend. I have a friend there with an apartment, flights are cheap in the off season, and I’ve never been there before. As might have been expected, I learned absolutely nothing about France. But I did come away with a lot of food for thought about America – specifically, how books work in the United States. Says Gilles Deleuze: “travel does not connect places, but affirms only their difference.” He’s right: sometimes you needs to get away from a place to think about it.

Three observations, then, on how books work in the United States w/r/t my French observations. This post is perhaps less liberal in its interpretation of books than we usually are around here: bear with me for a bit, there’s still plenty of rampant generalizing.

* * * * *

Wandering around the Sorbonne, my friend & I came upon the Librerie Philosophique J. Vrin and went in. It’s a good-sized bookshop that’s devoted entirely to used and new philosophy books, mostly in French, although the neatly categorized shelves are noticeably peppered with other languages. On the Saturday evening I was there, it was full of browsing customers: it’s obviously a working bookstore. We don’t have philosophy book stores in the U.S. One finds, of course, no end of religious bookstores, but unless I’m tremendously mistaken, there’s none dedicated solely to philosophy. (And as far as I know, there’s only one poetry bookstore remaining in the U.S.)

It’s a(n admittedly minor) shock to find oneself in a philosophy bookstore. But a deeper question tugs at me: why aren’t there philosophy book stores in the United States? I’m certainly not qualified to judge what the existence of J. Vrin says about France, but its lack of an analogue in the U.S. clearly says something (besides the obvious “the market won’t support it”). Are we not thinking about big ideas and shipping them about in books? Are the only people who need to read Plato our neocon overlords? Why don’t we need books like these?

* * * * *

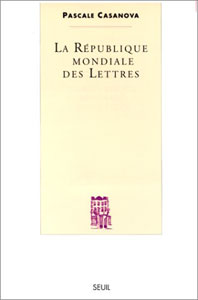

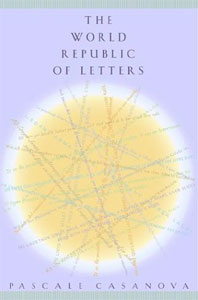

Another thing you notice at J. Vrin, as well as elsewhere in Paris: how monotone the books are. It’s not quite a color-coordinated bookstore but it’s close: just about every spine is white, a smaller number being yellow, a smattering of other colors. If you pull a book out, the cover designs are mostly in a classic French style: lots of space, Didot type, some discreet flourishes. These two are typical:

I’m not tremendously interested in French book style of itself, though: I’m more interested in what this minimalist tendency reveals about American book design and the ideas behind it. A trio of comparisons: the French on the left of each pair, the American on the right:

The American covers seem more designed – not necessarily better designed, that goes both ways – but they clearly exist as marketing. The French book covers aren’t advertising in the same way that the American book covers are. The implication here seems to be that French books are for reading, rather than for looking at. Nobody’s going to pick up one of those because of the way the cover looks. It’s presumed that the reader is already interested in the content of the book; what’s on the cover won’t change that interest. There’s a lot more variety in the American books: I might be persuaded to pick up the Deleuze book on Proust (where the quotation above came from) because it looks nice, or dissuaded from picking up the Amélie Nothomb book because it looks so horrible & the title was mangled into something out of Crate & Barrel.

There’s an essay by Jan Tschichold, the doyen of modern book design, advising the reader that the jacket of a hardcover book should be taken off and thrown away as soon as you get the book home. This seems heretical to a book collector (or designer), but I think his point ultimately makes sense: books shouldn’t exist as art objects, they exist to be read. Design should focus attention on, not deflect attention from, the ideas in the book. American book design has drifted away from that precept. (Tschichold, were he still alive, might argue that it’s failed entirely: that essay appears in a book titled The Form of the Book: Essays on the Morality of Good Design which has hardened into an art object: get a used copy for $102.50.)

There’s an essay by Jan Tschichold, the doyen of modern book design, advising the reader that the jacket of a hardcover book should be taken off and thrown away as soon as you get the book home. This seems heretical to a book collector (or designer), but I think his point ultimately makes sense: books shouldn’t exist as art objects, they exist to be read. Design should focus attention on, not deflect attention from, the ideas in the book. American book design has drifted away from that precept. (Tschichold, were he still alive, might argue that it’s failed entirely: that essay appears in a book titled The Form of the Book: Essays on the Morality of Good Design which has hardened into an art object: get a used copy for $102.50.)

Probably I didn’t need to go to France to figure this out: scrutinizing the Spanish and Bangla bookshops and bookcarts in my neighborhood reveals book covers that are closer to French than American design.

* * * * *

Back to advertising: in the windows of wine bars, one sees volumes of Deleuze and Julia Kristeva, not exactly what we usually construe as light café reading. These books are cultural signifiers: presumably the right sort of passersby see them and understand that the winebar is the right sort of place for people like them. Could you do this in the U.S.? You could; by putting Stanley Cavell and Peter Singer in the window, I suspect that you’d attract a lot of confusion and maybe, if you were lucky, some shabby grad students. In Paris: pretty people. (Are they actually interested in Kristeva and Deleuze, or are they just interested in the wine? Again: no idea.)

It’s worth pointing out that Paris didn’t seem technologically reactionary to me: books haven’t succeeded at the expense of newer media. Paris is full of wireless, for example, and URLs are splattered all over advertisements. If anything, books seem to have succeeded with new media: a casual flip through the enormous number of channels on my friend’s television yielded a couple of book review programs. Again: books are part of the cultural discourse there in a way that isn’t the case here.

* * * * *

I haven’t mentioned snobbery yet, though that’s obviously an essential part of this discourse. No one imagines that the majority of the French care that much about Derrida, and it’s clear the French have their own problems which don’t need my interpretations. And more importantly: it would be foolish to jump to the conclusion that America is anti-literary. I’m reminded of the bit in Proust’s Time Regained where the Baron de Charlus, equally drawn to both sides in WWI, declares himself pro-German because he’s surrounded by people parroting pro-French platitudes and he can’t stand them. I won’t deny that there’s a little bit of Charlus in my stance. But I do think that the lens of snobbery can be a useful way to scrutinize how cultural capital works, and this analysis can be broadened to look at the sort of big-picture questions we’re interested in at the Institute. Nor am I the only one who’s noticed this: a better analysis than my own can be found in Pascale Casanova’s The World Republic of Letters (depicted above in both French and American editions), a book from a few years ago:

. . . New York and London cannot be said to have replaced Paris in the structure of literary power: one can only note that, as a result of the generalization of the Anglo-American model and the growing influence of financial considerations, these two capitals tend to acquire more and more power in the literary world. But one must not oversimplify the situation by applying a political analysis that opposes Paris to New York and London, or France to the United States.”

(p. 168.) Casanova’s book is a nice (and readable) study of how literature functions globally as cultural capital; this review by William Deresiewicz in The Nation is a serviceable introduction. It’s a useful text for thinking about how big ideas have historically been “legitimated” (her term) and disseminated. Along the way, she can’t help but make a strong case for Paris being the historic arbiter of much of the world’s taste: Joyce, Faulkner, Borges, Wiesel (a list which could be extended at length) all first came to global prominence through French interest.

Another reminder that things are different in different countries: earlier this week, Pedro Meyer, the Mexican photographer who runs ZoneZero had a long lunch with the Institute, where he reiterated that the way books function in the U.S. is not necessarily the way they function in Latin America, where books are much scarcer and bookshops generally nonexistent. Meyer’s concerns echo those of Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe who blisters at American critics arguing that African novels are universal, only with different names:

“Does it ever occur to these [academics] to try out their game of changing names of characters and places in an American novel, say, a Philip Roth or an Updike, and slotting in African names just to see how it works? But of course it would not occur to them. It would never occur to them to doubt the universality of their own literature. In the nature of things the work of a Western writer is automatically informed by universality. It is only others who must strain to achieve it . . . I should like to see the word ‘universal’ banned altogether from discussions of African literature until such time as people cease to use it as a synonym for the narrow, self-serving parochialism of Europe, until their horizon extends to include all the world.”

(p. 156 in Casanova.) Culture cuts both ways. It’s important to remember that the ways books (and, by extension, their electronic analogues) function in American society isn’t the only way they can or should function. We tend to fall into the assumption that there is no alternative to the way we live. This is myopia, a myopia we need to continually recognize.

two newspapers

I picked up The New York Times from outside my door this morning knowing that the lead headline was going to be wrong. I still read the print paper every morning – I do read the electronic version, but I find that my reading there tends to be more self-selecting than I’d like it to be – but lately I find myself checking the Web before settling down to the paper and a cup of coffee. On the Web, I’d already seen the predictable gloating and hand-wringing in evidence there. Because of some communication mixup, the papers went to press with the information that the trapped West Virginia coal miners were mostly alive; a few hours later it turned out that they were, in fact, mostly dead. A scrutiny of the front pages of the New York dailies at the bodega this morning revealed that just about all had the wrong news – only Hoy, a Spanish-language daily didn’t have the story, presumably because it went to press a bit earlier. At right is the front page of today’s USA Today, the nation’s most popular newspaper; click on the thumbnail for a more legible version. See also the gallery at their “newseum”. (Note that this link won’t show today’s papers tomorrow – my apologies, readers of the future, there doesn’t seem to be anything that can be done for you, copyright and all that.)

I picked up The New York Times from outside my door this morning knowing that the lead headline was going to be wrong. I still read the print paper every morning – I do read the electronic version, but I find that my reading there tends to be more self-selecting than I’d like it to be – but lately I find myself checking the Web before settling down to the paper and a cup of coffee. On the Web, I’d already seen the predictable gloating and hand-wringing in evidence there. Because of some communication mixup, the papers went to press with the information that the trapped West Virginia coal miners were mostly alive; a few hours later it turned out that they were, in fact, mostly dead. A scrutiny of the front pages of the New York dailies at the bodega this morning revealed that just about all had the wrong news – only Hoy, a Spanish-language daily didn’t have the story, presumably because it went to press a bit earlier. At right is the front page of today’s USA Today, the nation’s most popular newspaper; click on the thumbnail for a more legible version. See also the gallery at their “newseum”. (Note that this link won’t show today’s papers tomorrow – my apologies, readers of the future, there doesn’t seem to be anything that can be done for you, copyright and all that.)

At left is another front page of a newspaper, The New York Times from April 20, 1950 (again, click to see a legible version). I found it last night at the start of Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. Published in 1951, The Mechanical Bride is one of McLuhan’s earliest works; in it, he primarily looks at the then-current world of print advertising, starting with the front page shown here. To my jaundiced eye, most of the book hasn’t stood up that well; while it was undoubtedly very interesting at the time – being one of the first attempts to seriously deal with how people interact with advertisements from a critical perspective – fifty years, and billions and billions of advertisements later, it doesn’t stand up as well as, say, Judith Williamson‘s Decoding Advertisements manages to. But bits of it are still interesting: McLuhan presents this front page to talk about how Stephane Mallarmé and the Symbolists found the newspaper to be the modern symbol of their day, with the different stories all jostling each other for prominence on the page.

At left is another front page of a newspaper, The New York Times from April 20, 1950 (again, click to see a legible version). I found it last night at the start of Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. Published in 1951, The Mechanical Bride is one of McLuhan’s earliest works; in it, he primarily looks at the then-current world of print advertising, starting with the front page shown here. To my jaundiced eye, most of the book hasn’t stood up that well; while it was undoubtedly very interesting at the time – being one of the first attempts to seriously deal with how people interact with advertisements from a critical perspective – fifty years, and billions and billions of advertisements later, it doesn’t stand up as well as, say, Judith Williamson‘s Decoding Advertisements manages to. But bits of it are still interesting: McLuhan presents this front page to talk about how Stephane Mallarmé and the Symbolists found the newspaper to be the modern symbol of their day, with the different stories all jostling each other for prominence on the page.

But you don’t – at least, I don’t – immediately see that when you look at the front page that McLuhan exhibits. This was presumably an extremely ordinary front page when he was exhibiting it, just as the USA Today up top might be representative today. Looked at today, though, it’s something else entirely, especially when you what newspapers look like now. You can notice this even in my thumbnails: when both papers are normalized to 200 pixels wide, you can’t read anything in the old one, besides that it says “The New York Times” as the top, whereas you can make out the headlines to four stories in the USA Today. Newspapers have changed, not just from black & white to color, but in the way the present text and images. In the old paper there are only two photos, headshots of white men in the news – one a politician who’s just given a speech, the other a doctor who’s had his license revoked. The USA Today has perhaps an analogue to that photo in Jack Abramoff’s perp walk; it also has five other photos, one of the miners’ deluded family members (along with Abramoff, the only news photos), two sports-related photos – one of which seems to be stock footage of the Rose Bowl sign, a photo advertising television coverage inside, and a photo of two students for a human interest story. This being the USA Today, there’s also a silly graph in the bottom left; the green strip across the bottom is an ad.

Photos and graphics take up more than a third of the front page of today’s paper.

What’s overwhelming to me about the old Times cover is how much text there is. This was not a newspaper that was meant to be read at a glance – as you can do with the thumbnail of the USA Today. If you look at the Times more closely it looks like everything on the front page is serious news. You could make an argument here about the decline of journalism, but I’m not that interested in that. More interesting is how visual print culture has become. Technology has enabled this – a reasonably intelligent high-schooler could, I think, create a layout like the USA Today. But having this possibility available would also seem to have had an impact on the content – and whether McLuhan would have predicted that, I can’t say.

everything bad is . . .

first up: I appreciate you coming over to defend yourself. The blogosphere is far too often self-reinforcing – the left (for example) reads left-leaning blogs and the right reads right-leaning blogs & there’s not a lot of dialogue between people on opposite sides, to everyone’s loss.

Here’s something that’s been nagging me for the past week or so: your book seems to effectively be conservative. Bear with me for a bit: I’m not saying that it’s Bill O’Reilly-style invective. I do think, however, that it effectively reinforces the status quo. Would I be wrong in taking away as the message of the book the chain of logic that:

- Our pop culture’s making us smarter.

- Therefore it must be good.

- Therefore we don’t need to change what we’re doing.

I’ll wager that you wouldn’t sign off on (3) & would argue that your book isn’t in the business of prescribing further action. I’m not accusing you of having malicious intentions, and we can’t entirely blame a writer for the distortions we bring to their work as readers (hey Nietzsche!). But I think (3)’s implicitly in the book: this is certainly the message most reviewers, at least, seem to be taking away from the book. Certainly you offer caveats (if the kids are watching television, there’s good television & there’s bad television), but I think this is ultimately a Panglossian view of the world: everything is getting better and better, we just need to stand back and let pop culture work upon us. Granted, the title may be a joke, but can you really expect us, the attention-deficit-addled masses, to realize that?

Even to get to (2) in that chain of reasoning, you need to buy into (1), which I don’t know that I do. Even before you can prove that rising intelligence is linked to the increased complexity of popular culture – which I’ll agree is interesting & does invite scrunity – you need to make the argument that intelligence is something that can be measured in a meaningful way. Entirely coincidentally – really – I happened to re-read Stephen Jay Gould’s Mismeasure of Man before starting in on EBIGFY; not, as I’m sure you know, a happy combination, but I think a relevant one. Not to reopen the internecine warfare of the Harvard evolutionary biology department in the 1990s, but I think the argument that Gould wrings out of the morass of intelligence/IQ studies still holds: if you know who your “smart” kids are, you can define “smartness” in their favor. There remain severe misgivings about the concept of g, which you skirt: I’m not an expert on the current state of thought on IQ, so I’ll skirt this too. But I do think it’s worth noting that while you’re not coming to Murray & Herrnstein’s racist conclusions, you’re still making use of the same data & methodology they used for The Bell Curve, the same data & methodology that Gould persuasively argued was fundamentally flawed. Science, the history of intelligence testing sadly proves, doesn’t exist outside of a political and economic context.

But even if smartness can be measured as an abstract quantity and if we are “smarter” than those of times past, to what end? This is the phrase I found myself writing over and over in the margin of your book. Is there a concrete result in this world of our being better at standardized tests? Sure, it’s interesting that we seem to be smarter, but what does that mean for us? Maybe the weakest part of your book argues that we’re now able to do a better job of picking political leaders. Are you living in the same country I’m living in? and watching the same elections? If we get any smarter, we’ll all be done for.

I’ll grant that you didn’t have political intentions in writing this, but the ramifications are there, and need to be explored if we’re going to seriously engage with your ideas. Technology – the application of science to the world in which we live – can’t exist in an economic and political vacuum.

everything bad continued — the author strikes back

Folks, enjoying the discussion here. I had a couple of responses to several points that have been raised.

1. The title. I think some of you are taking it a little too seriously — it’s meant to be funny, not a strict statement of my thesis. Calling it hyperbolic or misleading is like criticizing Neil Postman for calling his book “Amusing Ourselves To Death” when no one actually *died* from watching too much television in the early eighties.

2. IQ. As I say in the book, we don’t really know if the increased complexity of the culture is partially behind the Flynn Effect, though I suspect it is (and Flynn, for what it’s worth, suspects it is as well.) But I’m not just interested in IQ as a measure of the increased intelligence of the gaming/net generation. I focused on that because it was the one area where there was actually some good data, in the sense that we definitely know that IQ scores are rising. But I suspect that there are many other — potentially more important — ways in which we’re getting smarter as well, most of which we don’t test for. Probably the most important is what we sometimes call system thinking: analyzing a complex system with multiple interacting variables changing over time. IQ scores don’t track this skill at all, but it’s precisely the sort of thing you get extremely good at if you play a lot of SimCity-like games. It is not a trivial form of intelligence at all — it’s precisely the *lack* of skill at this kind of thinking that makes it hard for people to intuitively understand things like ecosystems or complex social problems.

3. The focus of the book itself. People seem to have a hard time accepting the fact that I really do think the content/values discussion about pop culture has its merits. I just chose to write a book that would focus on another angle, since it was an angle that was chronically ignored in the discussion of pop culture (or chronically misunderstood.) Everything Bad is not a unified field theory of pop culture; it’s an attempt to look at one specific facet of the culture from a fresh perspective. If Bob (and others) end up responding by saying that the culture is both making us smarter on a cognitive level, but less wise on a social/historical level (because of the materialism, etc) that’s a perfectly reasonable position to take, one that doesn’t contradict anything I’m saying in the book. I happen to think that — despite that limited perspective — the Sleeper Curve hypothesis was worthy of a book because 1) increased cognitive complexity is hardly a trivial development, and 2) everyone seemed to think that the exact opposite was happening, that the culture was dumbing us all down. In a way, I wrote the book to encourage people to spend their time worrying about real problems — instead of holding congressional hearings to decide if videogames were damaging the youth of American, maybe they could focus on, you know, poverty or global warming or untangling the Iraq mess.

As far as the materialistic values question goes, I think it’s worth pointing out that the most significant challenge to the capitalist/private property model to come along in generations has emerged precisely out of the gaming/geek community: open source software, gift economy sharing, wikipedia, peer-to-peer file sharing, etc. If you’re looking for evidence of people using their minds to imagine alternatives to the dominant economic structures of their time, you’ll find far more experiments in this direction coming out of today’s pop culture than you would have in the pop culture of the late seventies or eighties. Thanks to their immersion this networked culture, the “kids today” are much more likely to embrace collective projects that operate outside the traditional channels of commercial ownership. They’re also much more likely to think of themselves as producers of media, sharing things for the love of it, than the passive TV generation that Postman chronicled. There’s still plenty of mindless materialism out there, of course, but I think the trend is a positive one.

Steven