I just finished reading the Brennan Center for Justice’s report on fair use. This public policy report was funded in part by the Free Expression Policy Project and describes, in frightening detail, the state of public knowledge regarding fair use today. The problem is that the legal definition of fair use is hard to pin down. Here are the four factors that the courts use to determine fair use:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

From Dysfunctional Family Circus, a parody of the Family Circus cartoons. Find more details at illegal-art.org

Unfortunately, these criteria are open to interpretation at every turn, and have provided little with which to predict any judicial ruling on fair use. In a lawsuit, no one is sure of the outcome of their claim. This causes confusion and fear for individuals and publishers, academics and their institutions. In many cases where there is a clear fair use argument, the target of copyright infringement action (cease and desist, lawsuit) does not challenge the decision, usually for financial reasons. It’s just as clear that copyright owners pursue the protection of copyright incorrectly, with plenty of misapprehension about what qualifies for fair use. The current copyright law, as it has been written and upheld, is fraught with opportunities for mistakes by both parties, which has led to an underutilization of cultural assets for critical, educational, or artistic purposes. For the next two days, Ray and I are attending what hopes to be a fascinating conference in Cambridge, MA — The Economics of Open Content — co-hosted by Intelligent Television and MIT Open CourseWare. This project is a systematic study of why and how it makes sense for commercial companies and noncommercial institutions active in culture, education, and media to make certain materials widely available for free–and also how free services are morphing into commercial companies while retaining their peer-to-peer quality. They’ve assembled an excellent cross-section of people from the emerging open access movement, business, law, the academy, the tech sector and from virtually every media industry to address one of the most important (and counter-intuitive) questions of our age: how do you make money by giving things away for free?

Lawrence Lessig: Because as life moves online we should have the SAME FREEDOMS (at least) that we had in real life. There’s no doubt that in real life you could act out a movie or a different ending to a movie. There’s no doubt that would have been “free” of copyright in real life. But as we move online things that were before were free now are regulated.

Yesterday, Bob made the point that our memories increasingly exist outside of ourselves. At the institute, we have discussed the mediated life, and a substantial part of that mediation occurs as we continue to digitize more parts of our lives, from photo albums to diaries. Things we once created in the physical world now reside on the network, which means that it is being published. Photo albums documenting our trips to Disneyland or the Space Needle (whose facade is trademarked and protected) that one rested within the home, are uploaded to flickr, potentially accessible to anyone browsing the Internet, a regulated space. This regulation has enormous influence on the creative outlets of everyone, not just professionals. Without trying to sound overly naive, my concern is not just that speech and discourse of all people are being compromised. As companies become more litigious towards copyright infringement (especially when their arguments are weak), the safe guards of the courts and legislation are not protecting its constituents.

Lawrence Lessig: Copyright is about creating incentives. Incentives are prospective. No matter what even the US Congress does, it will not give Elvis any more incentive to create in 1954. So whatever the length of copyright should be prospectively, we know it can make no sense of incentives to extend the term for work that is already created.

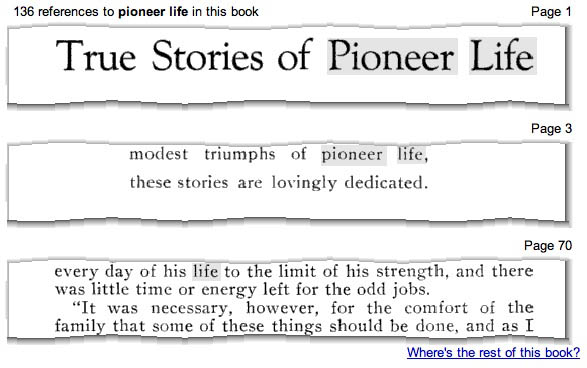

The increasing accessibility of digital technology allows people to become creators and distributors of content. Lessig notes that with each year, the increasing evidence from cases such as the Google Book Search controversy show the inadequacy of current copyright legislation. Further, he insightfully suggests to learn from the creations that young people produce such as anime music videos. Their completely different approach to intellectual property informs the cultural shift that is running counter to the legal status quo. Lessig suggest that these creative works have the potential to inform policy makers that these attitudes are moving toward the original intentions of copyright law. Then, policy makers hopefully may begin to question why these works are currently considered illegal. I just noticed that Google Book Search requires users to be logged in on a Google account to view pages of copyrighted works. Why do I have to log in to see certain pages? So they’re tracking how much we’ve looked at and capping our number of page views. Presumably a bone tossed to publishers, who I’m sure will continue suing Google all the same (more on this here). There’s also the possibility that publishers have requested information on who’s looking at their books — geographical breakdowns and stats on click-throughs to retailers and libraries. I doubt, though, that Google would share this sort of user data. Substantial privacy issues aside, that’s valuable information they want to keep for themselves. Anyone who’s ever seen a book has seen ISBNs, or International Standard Book Numbers — that string of ten digits, right above the bar code, that uniquely identifies a given title. Now come ESBNs, or Electronic Standard Book Numbers, which you’d expect would be just like ISBNs, only for electronic books. And you’d be right, but only partly. In the West, the desire to blur the line, the need to access the “other side,” took artists to try opium, absinth, kef, and peyote. The symbolists crossed the line and brought back dada, surrealism, and other manifestations of worlds that until then had been held at bay but that were all there. The virtual is part of the actual, “we, or objects acting on our behalf are online all the time.” Never though of that in such terms, but it’s true, and very exciting. It potentially enriches my reality. As with a book, contents become alive through the reader/user, otherwise the book is a dead, or dormant, object. So, my e-mail, the blogs I read, the Web, are online all the time, but it’s through me that they become concrete, a perceived reality. Yes, we read differently because texts grow, move, and evolve, while we are away and “the object” is closed. But, we still need to read them. Esse rerum est percipi. …cyberspace expresses a desire to transcend the world; Web 2.0 is about engaging with it. The early inhabitants of cyberspace were like the early Church monastics, who sought to serve God by going into the desert and escaping the temptations and distractions of the world and the flesh. The vision of Web 2.0, in contrast, is more Franciscan: one of engagement with and improvement of the world, not escape from it. The end of cyberspace may mean the fusion of real and virtual worlds, another layer of a massively mediated existence. And this raises many questions about what is real and how, or if, that matters. But the end of cyberspace, despite all the sweeping gospel of Web 2.0, continuous computing, urban computing etc., also signals the beginning of something terribly mundane. Networks of fiber and digits are still human networks, prone to corruption and virtue alike. A virtual environment is still a natural environment. The extraordinary, in time, becomes ordinary. And undoubtedly we will still search for lines to cross. interesting question came up today in the office. there’s a site, surferdiary.com, that reposts every entry on if:book. they do the same for several other sites, presumably as a way to generate traffic to their site and ultimately to gather clicks on their google supplied ads. if:book entries are posted with a creative commons license which allows reuse with proper attribution but forbids commercial use. surferdiary’s use seems to be thoroughly commercial. some of my colleagues think we should go after them as a way of defending the creative commons concept. would love to know what people think? For an alternative view of Lisa’s earlier post … i wonder if Gamma’s submission of Adam Stacey’s image with the “Adam Stacey/Gamma” attribution doesn’t show the strength of the Creative Commons concept. As i see it, Stacey published his image without any restrictions beyond attribution. Gamma, a well-respected photo agency started distributing the image attributed to Stacey. Isn’t this exactly what the CC license was supposed to enable — the free-flow of information on the net. perhaps Stacey chose the wrong license and he didn’t mean for his work to be distributed by a for-profit company. If so, that is a reminder to all of us to be careful about which Creative Commons license we choose. One thing i’m not clear on is whether Gamma referenced the CC license. They are supposed to do that and if they didn’t they should have. Last night I attended a fascinating panel discussion at the American Bar Association on the legality of Google Book Search. In many ways, this was the debate made flesh. Making the case against Google were high-level representatives from the two entities that have brought suit, the Authors’ Guild (Executive Director Paul Aiken) and the Association of American Publishers (VP for legal counsel Allan Adler). It would have been exciting if Google, in turn, had sent representatives to make their case, but instead we had two independent commentators, law professor and blogger Susan Crawford and Cameron Stracher, also a law professor and writer. The discussion was vigorous, at times heated — in many ways a preview of arguments that could eventually be aired (albeit under a much stricter clock) in front of federal judges. The long-term risk of privatization is simple: Companies change and fail. Libraries and universities last…..Libraries should not be relinquishing their core duties to private corporations for the sake of expediency. Whichever side wins in court, we as a culture have lost sight of the ways that human beings, archives, indexes, and institutions interact to generate, preserve, revise, and distribute knowledge. We have become obsessed with seeing everything in the universe as “information” to be linked and ranked. We have focused on quantity and convenience at the expense of the richness and serendipity of the full library experience. We are making a tremendous mistake. This essay contains in abundance what has largely been missing from the Google books debate: intellectual courage. Vaidhyanathan, an intellectual property scholar and “avowed open-source, open-access advocate,” easily could have gone the predictable route of scolding the copyright conservatives and spreading the Google gospel. But he manages to see the big picture beyond the intellectual property concerns. This is not just about economics, it’s about knowledge and the public interest. Google says it needs the data it keeps to improve its technology, but it is doubtful it needs so much personally identifiable information. Of course, this sort of data is enormously valuable for marketing. The whole idea of “Don’t be evil,” though, is resisting lucrative business opportunities when they are wrong. Google should develop an overarching privacy theory that is as bold as its mission to make the world’s information accessible – one that can become a model for the online world. Google is not necessarily worse than other Internet companies when it comes to privacy. But it should be doing better.

This restrictive atmosphere is even more prevalent in the film and music industries. The RIAA lawsuits are a well-known example of the industry protecting its assets via heavy-handed lawsuits. The culture of shared use in the movie industry is even more stifling. This combination of aggressive control by the studio and equally aggressive piracy is causing a legislative backlash that favors copyright holders at the expense of consumer value. The Brennan report points to several examples where the erosion of fair use has limited the ability of scholars and critics to comment on these audio/visual materials, even though they are part of the landscape of our culture.

That’s why

This entry was posted in brennan_center, copyright, Copyright and Copyleft, creative_commons, fair_use, law, open_content and tagged fair_use copyright brennan_center creative_commons open_content law on .

the economics of open content

Rather than continue, in an age of information abundance, to embrace economic models predicated on information scarcity, we need to look ahead to new models for sustainability and creative production. I look forward to hearing from some of the visionaries gathered in this room.

More to come…

lessig in second life

Wednesday evening, I attended an interview with Larry Lessig, which took place in the virtual world of Second Life. New World Notes announced the event and is posting coverage and transcripts of the interview. As it was my first experience in SL, I will post more on the experience of attending an interview/ lecture in a virtual space. For now, I am going to comment upon two quotes that Lessig covered as it relates to our work at the institute.

The courts’ failure to clearly define an interpretation of fair use puts at risk the discourse that a functioning democracy requires. The stringent attitudes towards using copyrighted material goes against the spirit of the original intentions of the law. Although, it may not be a role of the government and the courts to actively encourage creativity. It is sad that bipartisan government actions and courts rulings actively discourage innovation and creativity.

the book is reading you

They provide the following explanation:

Because many of the books in Google Book Search are still under copyright, we limit the amount of a book that a user can see. In order to enforce these limits, we make some pages available only after you log in to an existing Google Account (such as a Gmail account) or create a new one. The aim of Google Book Search is to help you discover books, not read them cover to cover, so you may not be able to see every page you’re interested in.

That’s because “the aim of Google Book Search” is also to discover who you are. It’s capturing your clickstreams, analyzing what you’ve searched and the terms you’ve used to get there. The book is reading you. Substantial privacy issues aside, (it seems more and more that’s where we’ll be leaving them) Google will use this data to refine Google’s search algorithms and, who knows, might even develop some sort of personalized recommendation system similar to Amazon’s — you know, where the computer lists other titles that might interest you based on what you’ve read, bought or browsed in the past (a system that works only if you are logged in). It’s possible Google is thinking of Book Search as the cornerstone of a larger venture that could compete with Amazon.

There are many ways Google could eventually capitalize on its books database — that is, beyond the contextual advertising that is currently its main source of revenue. It might turn the scanned texts into readable editions, hammer out licensing agreements with publishers, and become the world’s biggest ebook store. It could start a print-on-demand service — a Xerox machine on steroids (and the return of Google Print?). It could work out deals with publishers to sell access to complete online editions — a searchable text to go along with the physical book — as Amazon announced it will do with its Upgrade service. Or it could start selling sections of books — individual pages, chapters etc. — as Amazon has also planned to do with its Pages program.

Amazon has long served as a valuable research tool for books in print, so much so that some university library systems are now emulating it. Recent additions to the Search Inside the Book program such as concordances, interlinked citations, and statistically improbable phrases (where distinctive terms in the book act as machine-generated tags) are especially fun to play with. Although first and foremost a retailer, Amazon feels more and more like a search system every day (and its A9 engine, though seemingly always on the back burner, is also developing some interesting features). On the flip side Google, though a search system, could start feeling more like a retailer. In either case, you’ll have to log in first.

ESBNs and more thoughts on the end of cyberspace

ESBNs, which just came into existence this year, uniquely identify not only an electronic title, but each individual copy, stream, or download of that title — little tracking devices that publishers can embed in their content. And not just books, but music, video or any other discrete media form — ESBNs are media-agnostic.

ESBNs, which just came into existence this year, uniquely identify not only an electronic title, but each individual copy, stream, or download of that title — little tracking devices that publishers can embed in their content. And not just books, but music, video or any other discrete media form — ESBNs are media-agnostic.

“It’s all part of the attempt to impose the restrictions of the physical on the digital, enforcing scarcity where there is none,” David Weinberger rightly observes. On the net, it’s not so much a matter of who has the book, but who is reading the book — who is at the book. It’s not a copy, it’s more like a place. But cyberspace blurs that distinction. As Alex Pang explains, cyberspace is still a place to which we must travel. Going there has become much easier and much faster, but we are still visitors, not natives. We begin and end in the physical world, at a concrete terminal.

When I snap shut my laptop, I disconnect. I am back in the world. And it is that instantaneous moment of travel, that light-speed jump, that has unleashed the reams and decibels of anguished debate over intellectual property in the digital era. A sort of conceptual jetlag. Culture shock. The travel metaphors begin to falter, but the point is that we are talking about things confused during travel from one world to another. Discombobulation.

This jetlag creates a schism in how we treat and consume media. When we’re connected to the net, we’re not concerned with copies we may or may not own. What matters is access to the material. The copy is immaterial. It’s here, there, and everywhere, as the poet said. But when you’re offline, physical possession of copies, digital or otherwise, becomes important again. If you don’t have it in your hand, or a local copy on your desktop then you cannot experience it. It’s as simple as that. ESBNs are a byproduct of this jetlag. They seek to carry the guarantees of the physical world like luggage into the virtual world of cyberspace.

But when that distinction is erased, when connection to the network becomes ubiquitous and constant (as is generally predicted), a pervasive layer over all private and public space, keeping pace with all our movements, then the idea of digital “copies” will be effectively dead. As will the idea of cyberspace. The virtual world and the actual world will be one.

For publishers and IP lawyers, this will simplify matters greatly. Take, for example, webmail. For the past few years, I have relied exclusively on webmail with no local client on my machine. This means that when I’m offline, I have no mail (unless I go to the trouble of making copies of individual messages or printouts). As a consequence, I’ve stopped thinking of my correspondence in terms of copies. I think of it in terms of being there, of being “on my email” — or not. Soon that will be the way I think of most, if not all, digital media — in terms of access and services, not copies.

But in terms of perception, the end of cyberspace is not so simple. When the last actual-to-virtual transport service officially shuts down — when the line between worlds is completely erased — we will still be left, as human beings, with a desire to travel to places beyond our immediate perception. As Sol Gaitan describes it in a brilliant comment to yesterday’s “end of cyberspace” post: Just the other night I saw a fantastic performance of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl that took the poem — which I’d always found alluring but ultimately remote on the page — and, through the conjury of five actors, made it concrete, a perceived reality. I dug Ginsburg’s words. I downloaded them, as if across time. I was in cyberspace, but with sweat and pheremones. The Beats, too, sought sublimity — transport to a virtual world. So, too, did the cyberpunks in the net’s early days. So, too, did early Christian monastics, an analogy that Pang draws:

Just the other night I saw a fantastic performance of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl that took the poem — which I’d always found alluring but ultimately remote on the page — and, through the conjury of five actors, made it concrete, a perceived reality. I dug Ginsburg’s words. I downloaded them, as if across time. I was in cyberspace, but with sweat and pheremones. The Beats, too, sought sublimity — transport to a virtual world. So, too, did the cyberpunks in the net’s early days. So, too, did early Christian monastics, an analogy that Pang draws:

defending the creative commons license

another view on the stacey/gamma flap

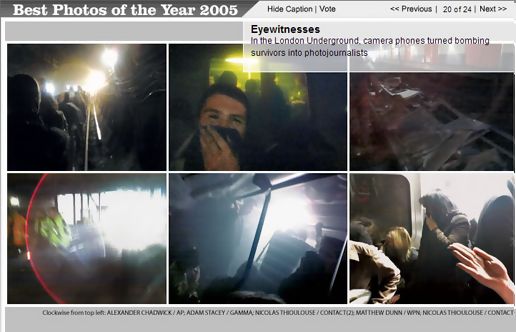

phone photo of london underground nominated for time best photo; photo agency claims credit for creative commons work

Moblog co-founder Alfie Dennen is furious that the photo agency Gamma has claimed credit for a well-known photo of last summer’s London subway bombing –first circulated on Moblog under a Creative Commons liscence — that was chosen for Time’s annual Best Photo contest. Dennen and others in the blogosphere are hoping that photographer Adam Stacey might take legal action against Gamma for what seems to be a breach of copyright.

We at the Institute are still trying to figure out what to make of this. Like everyone else who has been observing the increasing popularity of the Creative Commons license, we’ve been wondering when and how the license will be tested in court. However, this might not be the best possible test case. On one hand, it seems to be a somewhat imperious “claiming” of a photo widely celebrated for being produced by a citizen journalist who was committed to its free circulation. One the other hand, it seems unclear whether Dennen and/or Stacey are correct in their assertion that the CC license that was used really prohibits Gamma from attaching their name to the photo.

The photo in question, a shot of gasping passengers evacuating the London Underground in the moments after last summer’s bombing (in the image above, it’s the second photo clockwise), was snapped by Stacey using the camera on his cellphone. Time’s nomination of the photo most likely reflects the fact that the photo itself — and Stacey — became something of a media phenomenon in the weeks following the bombing. The image was posted on Moblog about 15 minutes after the bombing, and then widely circulated in both print and online media venues. Stacey subsequently appeared on NPR’s All Things Considered, and the photo was heralded as a signpost that citizen journalism had come into its own.

While writing about the photo’s appearance in Time, Dennen noticed that Time had credited the photo to Adam Stacey/Gamma instead of Adam Stacey/Creative Commons. According to Dennen, Stacey had been contacted by Gamma and had turned down their offer to distribute the photo, so the attribution came as an unpleasant shock. He claims that the license chosen by Stacey clearly indicates that the photo be given Creative Commons attribution. But is this really clear? The photo is attributed to Stacey, but not to Creative Commons: does this create a grey area? The license does allow commercial use of Stacey’s photo, so if Gamma was making a profit off the image, that would be legal as well.

Dennen writes on his weblog that he contacted Gamma for an explanation, arguing that after Stacey told the agency that he wanted to distribute the photo through Creative Commons, they should have understood that they could use it, but not claim it as their own. Gamma responded in an email that, “[we] had access to this pix on the web as well as anyone, therefore we downloaded it and released it under Gamma credit as all agencies did or could have done since there was no special requirement regarding the credit.” They also claimed that in their conversation with Stacey, Creative Commons never came up, and that a “more complete answer” to the reason for the attribution would be available after January 3rd, when the agent who spoke with Stacey returned from Christmas vacation.

Until then, it’s difficult to say whether Gamma’s claim of credit for the photo is accidental or deliberate disregard. Dennen also says that he’s contacting Time to urge them to issue a correction, but he hasn’t gotten a response yet. I’ll follow this story as it develops.

google book search debated at american bar association

The lawsuits in question center around whether Google’s scanning of books and presenting tiny snippet quotations online for keyword searches is, as they claim, fair use. As I understand it, the use in question is the initial scanning of full texts of copyrighted books held in the collections of partner libraries. The fair use defense hinges on this initial full scan being the necessary first step before the “transformative” use of the texts, namely unbundling the book into snippets generated on the fly in response to user search queries.

…in case you were wondering what snippets look like

At first, the conversation remained focused on this question, and during that time it seemed that Google was winning the debate. The plaintiffs’ arguments seemed weak and a little desperate. Aiken used carefully scripted language about not being against online book search, just wanting it to be licensed, quipping “we’re just throwing a little gravel in the gearbox of progress.” Adler was a little more strident, calling Google “the master of misdirection,” using the promise of technological dazzlement to turn public opinion against the legitimate grievances of publishers (of course, this will be settled by judges, not by public opinion). He did score one good point, though, saying Google has betrayed the weakness of its fair use claim in the way it has continually revised its description of the program.

Almost exactly one year ago, Google unveiled its “library initiative” only to re-brand it several months later as a “publisher program” following a wave of negative press. This, however, did little to ease tensions and eventually Google decided to halt all book scanning (until this past November) while they tried to smooth things over with the publishers. Even so, lawsuits were filed, despite Google’s offer of an “opt-out” option for publishers, allowing them to request that certain titles not be included in the search index. This more or less created an analog to the “implied consent” principle that legitimates search engines caching web pages with “spider” programs that crawl the net looking for new material.

In that case, there is a machine-to-machine communication taking place and web page owners are free to insert programs that instruct spiders not to cache, or can simply place certain content behind a firewall. By offering an “opt-out” option to publishers, Google enables essentially the same sort of communication. Adler’s point (and this was echoed more succinctly by a smart question from the audience) was that if Google’s fair use claim is so air-tight, then why offer this middle ground? Why all these efforts to mollify publishers without actually negotiating a license? (I am definitely concerned that Google’s efforts to quell what probably should have been an anticipated negative reaction from the publishing industry will end up undercutting its legal position.)

Crawford came back with some nice points, most significantly that the publishers were trying to make a pretty egregious “double dip” into the value of their books. Google, by creating a searchable digital index of book texts — “a card catalogue on steroids,” as she put it — and even generating revenue by placing ads alongside search results, is making a transformative use of the published material and should not have to seek permission. Google had a good idea. And it is an eminently fair use.

And it’s not Google’s idea alone, they just had it first and are using it to gain a competitive advantage over their search engine rivals, who in their turn, have tried to get in on the game with the Open Content Alliance (which, incidentally, has decided not to make a stand on fair use as Google has, and are doing all their scanning and indexing in the context of license agreements). Publishers, too, are welcome to build their own databases and to make them crawl-able by search engines. Earlier this week, Harper Collins announced it would be doing exactly that with about 20,000 of its titles. Aiken and Adler say that if anyone can scan books and make a search engine, then all hell will break loose and millions of digital copies will be leaked into the web. Crawford shot back that this lawsuit is not about net security issues, it is about fair use.

But once the security cat was let out of the bag, the room turned noticeably against Google (perhaps due to a preponderance of publishing lawyers in the audience). Aiken and Adler worked hard to stir up anxiety about rampant ebook piracy, even as Crawford repeatedly tried to keep the discussion on course. It was very interesting to hear, right from the horse’s mouth, that the Authors’ Guild and AAP both are convinced that the ebook market, tiny as it currently is, is within a few years of exploding, pending the release of some sort of ipod-like gadget for text. At that point, they say, Google will have gained a huge strategic advantage off the back of appropriated content.

Their argument hinges on the fourth determining factor in the fair use exception, which evaluates “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” So the publishers are suing because Google might be cornering a potential market!!! (Crawford goes further into this in her wrap-up) Of course, if Google wanted to go into the ebook business using the material in their database, there would have to be a licensing agreement, otherwise they really would be pirating. But the suits are not about a future market, they are about creating a search service, which should be ruled fair use. If publishers are so worried about the future ebook market, then they should start planning for business.

To echo Crawford, I sincerely hope these cases reach the court and are not settled beforehand. Larger concerns about Google’s expansionist program aside, I think they have made a very brave stand on the principle of fair use, the essential breathing space carved out within our over-extended copyright laws. Crawford reminded the room that intellectual property is NOT like physical property, over which the owner has nearly unlimited rights. Copyright is a “temporary statutory monopoly” originally granted (“with hesitation,” Crawford adds) in order to incentivize creative expression and the production of ideas. The internet scares the old-guard publishing industry because it poses so many threats to the security of their product. These threats are certainly significant, but they are not the subject of these lawsuits, nor are they Google’s, or any search engine’s, fault. The rise of the net should not become a pretext for limiting or abolishing fair use.

sober thoughts on google: privatization and privacy

Siva Vaidhyanathan has written an excellent essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education on the “risky gamble” of Google’s book-scanning project — some of the most measured, carefully considered comments I’ve yet seen on the issue. His concerns are not so much for the authors and publishers that have filed suit (on the contrary, he believes they are likely to benefit from Google’s service), but for the general public and the future of libraries. Outsourcing to a private company the vital task of digitizing collections may prove to have been a grave mistake on the part of Google’s partner libraries. Siva:

What irks me about the usual debate is that it forces you into a position of either resisting Google or being its apologist. But this fails to get at the real bind we all are in: the fact that Google provides invaluable services and yet is amassing too much power; that a private company is creating a monopoly on public information services. Sooner or later, there is bound to be a conflict of interest. That is where we, the Google-addicted public, are caught. It’s more complicated than hip versus square, or good versus evil.

Here’s another good piece on Google. On Monday, The New York Times ran an editorial by Adam Cohen that nicely lays out the privacy concerns: Two graduate students in Stanford in the mid-90s recognized that search engines would the most important tools for dealing with the incredible flood of information that was then beginning to swell, so they started indexing web pages and working on algorithms. But as the company has grown, Google’s admirable-sounding mission statement — “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” — has become its manifest destiny, and “information” can now encompass the most private of territories.

At one point it simply meant search results — the answers to our questions. But now it’s the questions as well. Google is keeping a meticulous record of our clickstreams, piecing together an enormous database of queries, refining its search algorithms and, some say, even building a massive artificial brain (more on that later). What else might they do with all this personal information? To date, all of Google’s services are free, but there may be a hidden cost.

“Don’t be evil” may be the company motto, but with its IPO earlier this year, Google adopted a new ideology: they are now a public corporation. If web advertising (their sole source of revenue) levels off, then investors currently high on $400+ shares will start clamoring for Google to maintain profits. “Don’t be evil to us!” they will cry. And what will Google do then?

images: New York Public Library reading room by Kalloosh via Flickr; archive of the original Google page