Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

I’m a bit puzzled by the Playaways. I can understand why publishing industry executives would be excited about them, but I’m not so about consumers. The self-contained players are being marketed to an audience that wants an audiobook but doesn’t want to be bothered with CD or MP3 players. The happy customers pictured on the Playaway website are both young and middle aged, but I suspect the real audience for these players would be older Americans who have sworn off computer literacy, and I don’t know that these folks are listening to audio books through headphones.

Speaking of older Americans, if you go down into my parent’s basement, you’ll see a few big shopping bags of books-on-tape that they bought, listened to once, and then found too expensive to throw out yet impossible to give away. This seems clearly to be the future of the Playaways, which can be listened to repeatedly (if you keep changing the batteries) but can’t play anything else than the book they were intended to play. The throwaway nature of the Playaway (suggested, of course, by the very name of the device) is addressed on the company’s website, which provides helpful suggestions on how to get rid of the things once you don’t want ’em anymore. According to the website, you can even ask the Playaway people to send you a stamped envelope addressed to a charitable organization that would be happy to take your Playaway.

This begs the obvious question: what if that organization wants to get rid of the Playway? And so on?

How many times will Playaway shell out a stamp to keep their players out of the landfill?

Category Archives: books

ebr is back

ebr is back after a several month hiatus during which time it was overhauled. The site, published by AltX was among the first places where the “technorati meets the literati” and I always found it attractive for its emphasis on sustained analysis of digital artifacts and the occasional pop culture reference. The latest project, first person series, seems to answer a lot of what bob finds attractive in the blogs of juan cole and others. And although I’ve heard ebr called “too linear” (as compared to Vectors, USC’s e-journal) the interface goes a long way toward solving the problem of the scrolling feature of many sites/blogs which privilege what’s new. The interweaving threads with search capabilities seem quite hearty.

pages á la carte

The New York Times reports on programs being developed by both Amazon and Google that would allow readers to purchase online access to specific sections of books — say, a single recipe from a cookbook, an individual chapter from a how-to manual, or a particular short story or poem from an anthology. Such a system would effectively “unbind” books into modular units that consumers patch into their online reading, just as iTunes blew apart the integrity of the album and made digital music all about playlists. We become scrapbook artists.

It seems Random House is in on this too, developing a micropayment model and consulting closely with the two internet giants. Pages would sell for anywhere between five and 25 cents each.

google print’s not-so-public domain

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

The problem is, there really isn’t all that much there. Google’s gotten a lot of bad press for its supposedly cavalier attitude toward copyright, but spend a few minutes browsing Google Print and you’ll see just how publisher-centric the whole affair is. The idea of a text being in the public domain really doesn’t amount to much if you’re only talking about antique manuscripts, and these are the only books that they’ve made fully accessible. Daisy Miller‘s copyright expired long ago but, with the exception of Harvard’s illustrated 1892 copy, all the available scanned editions are owned by modern publishers and are therefore only snippeted. This is not an online library, it’s a marketing program. Google Print will undeniably have its uses, but we shouldn’t confuse it with a library.

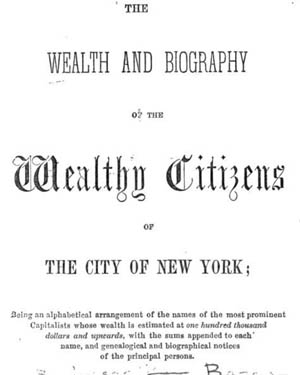

(An interesting offering from the stacks of the New York Public Library is this mid-19th century biographic registry of the wealthy burghers of New York: “Capitalists whose wealth is estimated at one hundred thousand dollars and upwards…”)

wikipedia hard copy

Believe it or not, they’re printing out Wikipedia, or rather, sections of it. Books for the developing world. Funny that just days ago Gary remarked:

“A Better Wikipedia will require a print version…. A print version would, for better or worse, establish Wikipedia as a cosmology of information and as a work presenting a state of knowledge.”

Prescient.

microsoft joins open content alliance

Microsoft’s forthcoming “MSN Book Search” is the latest entity to join the Open Content Alliance, the non-controversial rival to Google Print. ZDNet says: “Microsoft has committed to paying for the digitization of 150,000 books in the first year, which will be about $5 million, assuming costs of about 10 cents a page and 300 pages, on average, per book…”

Apparently having learned from Google’s mistakes, OCA operates under a strict “opt-in” policy for publishers vis-a-vis copyrighted works (whereas with Google, publishers have until November 1 to opt out). Judging by the growing roster of participants, including Yahoo, the National Archives of Britain, the University of California, Columbia University, and Rice University, not to mention the Internet Archive, it would seem that less hubris equals more results, or at least lower legal fees. Supposedly there is some communication between Google and OCA about potential cooperation.

Also story in NY Times.

to some writers, google print sounds like a sweet deal

Wired has a piece today about authors who are in favor of Google’s plans to digitize millions of books and make them searchable online. Most seem to agree that obscurity is a writer’s greatest enemy, and that the exposure afforded by Google’s program far outweighs any intellectual property concerns. Sometimes to get more you have to give a little.

The article also mentions the institute.

debating google print

The Washington Post has run a pair of op-eds, one from each side of the Google Print dispute. Neither says anything particularly new. Moreover, they enforce the perception that there can be only two positions on the subject — an endemic problem in newspaper opinion pages with their addiction to binaries, where two cardboard boxers are allotted their space to throw a persuasive punch. So you’re either for Google or against it? That’s awfully close to you’re either for technology — for progress — or against it. Unfortunately, like technology’s impact, the Google book-scanning project is a little trickier to figure out, and a more nuanced conversation is probably in order.

The first piece, “Riches We Must Share…”, is submitted in support of Google by University of Michigan President Sue Coleman (a partner in the Google library project). She argues that opening up the elitist vaults of the world’s great (english) research libraries will constitute a democratic revolution. “We believe the result can be a widening of human conversation comparable to the emergence of mass literacy itself.” She goes on to deliver some boilerplate about the “Net Generation” — too impatient to look for books unless they’re online etc. etc. (great to see a major university president being led by the students instead of leading herself).

Coleman then devotes a couple of paragraphs to the copyright question, failing to tackle any of its controversial elements:

Universities are no strangers to the responsible management of complex copyright, permission and security issues; we deal with them every day in our classrooms, libraries, laboratories and performance halls. We will continue to work within the current criteria for fair use as we move ahead with digitization.

The problem is, Google is stretching the current criteria of fair use, possibly to the breaking point. Coleman does not acknowledge or address this. She does, however, remind the plaintiffs that copyright is not only about the owners:

The protections of copyright are designed to balance the rights of the creator with the rights of the public. At its core is the most important principle of all: to facilitate the sharing of knowledge, not to stifle such exchange.

All in all a rather bland statement in support of open access. It fails to weigh in on the fair use question — something about which the academy should have a few things to say — and does not indicate any larger concern about what Google might do with its books database down the road.

The opposing view, “…But Not at Writers’ Expense”, comes from Nick Taylor, writer, and president of the Authors’ Guild (which sued Google last month). Taylor asserts that mega-rich Google is tramping on the dignity of working writers. But a couple of paragraphs in, he gets a little mixed up about contemporary publishing:

Except for a few big-name authors, publishers roll the dice and hope that a book’s sales will return their investment. Because of this, readers have a wealth of wonderful books to choose from.

A dubious assessment, since publishing conglomerates are not exactly enthusiastic dice rollers. I would counter that risk-averse corporate publishing has steadily shrunk the number of available titles, counting on a handful of blockbusters to drive the market. Taylor goes on to defend not just the publishing status quo, but the legal one:

Now that the Authors Guild has objected, in the form of a lawsuit, to Google’s appropriation of our books, we’re getting heat for standing in the way of progress, again for thoughtlessly wanting to be paid. It’s been tradition in this country to believe in property rights. When did we decide that socialism was the way to run the Internet?

First of all, it’s funny to think of the huge corporations that dominate the web as socialist. Second, this talk about being paid for appropriating books for a search database is revealing of the two totally different worldviews that are at odds in this struggle. The authors say that any use of their book requires a payment. Google sees including the books in the database as a kind of payment in itself. No one with a web page expects Google to pay them for indexing their site. They are grateful that they do! Otherwise, they are totally invisible. This is the unspoken compact that underpins web search. Google assumed the same would apply with books. Taylor says not so fast.

Here’s Taylor on fair use:

Google contends that the portions of books it will make available to searchers amount to “fair use,” the provision under copyright that allows limited use of protected works without seeking permission. That makes a private company, which is profiting from the access it provides, the arbiter of a legal concept it has no right to interpret. And they’re scanning the entire books, with who knows what result in the future.

Actually, Google is not doing all the interpreting. There is a legal precedent for Google’s reading of fair use established in the 2003 9th Circuit Court decision Kelly v. Arriba Soft. In the case, Kelly, a photographer, sued Arriba Soft, an online image search system, for indexing several of his photographs in their database. Kelly believed that his intellectual property had been stolen, but the court ruled that Arriba’s indexing of thumbnail-sized copies of images (which always linked to their source sites) was fair use: “Arriba’s use of the images serves a different function than Kelly’s use – improving access to information on the internet versus artistic expression.” Still, Taylor’s “with who knows what result in the future” concern is valid.

So on the one hand we have many writers and most publishers trying to defend their architecture of revenue (or, as Taylor would have it, their dignity). But I can’t imagine how Google Print would really be damaging that architecture, at least not in the foreseeable future. Rather it leverages it by placing it within the frame of another architecture: web search. The irony for the authors is that the current architecture doesn’t seem to be serving them terribly well. With print-on-demand gaining in quality and legitimacy, online book search could totally re-define what is an acceptable risk to publishers, and maybe more non-blockbuster authors would get published.

On the other hand we have the universities and libraries participating in Google’s program, delivering the good news of accessibility. But they are not sufficiently questioning what Google might do with its database down the road, or the implications of a private technology company becoming the principal gatekeeper of the world’s corpus.

If only this debate could be framed in a subtler way, rather than the for-Google-or-against-it paradigm we have now. I’m cautiously optimistic about the effect of having books searchable on the web. And I tend to believe it will be beneficial to authors and publishers. But I have other, deep reservations about the direction in which Google is heading, and feel that a number of things could go wrong. We think the cencorship of the marketplace is bad now in the age of publishing conglomerates. What if one company has total control of everything? And is keeping track of every book, every page, that you read. And is reading you while you read, throwing ads into your peripheral vision. I’m curious to hear from readers what they feel could be the hazards of Google Print.

google expands book-scanning project to europe

This week Google will be paying a visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair to talk with European publishers and chief librarians (including arch nemesis Jean-Nöel Jeanneney) about eight new local incarnations of Google Print. (more)

a future written in electronic ink?

Discussions about the future of newspapers often allude to a moment in the Steven Spielberg film “Minority Report,” set in the year 2054, in which a commuter on the train is reading something that looks like a paper copy of USA Today, but which seems to be automatically updating and rearranging its contents like a web page. This is a comforting vision for the newspaper business: reassigning the un-bottled genie of the internet to the familiar commodity of the broadsheet. But as with most science fiction, the fallacy lies in the projection of our contemporary selves into an imagined future, when in fact people and the way they read may have very much changed by the year 2054.

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Staffs are being cut, hiring freezes put into effect. Some newspapers (The Guardian in Britain and soon the Wall Street Journal) are changing the look and reducing the size of their print product to lure readers and cut costs. But given the rather grim forecast, some papers are beginning to ponder how other technologies might help them survive.

Last week, David Carr wrote in the Times about “an ipod for text” as a possible savior — a popular, portable device that would reinforce the idea of the newspaper as something you have in your hand, that you take with you, thereby rationalizing a new kind of subscription delivery. This weekend, the Washington Post hinted at what that device might actually be: a flexible, paper-like screen using “e-ink” technology.

An e-ink display is essentially a laminated sheet containing a thin layer of fluid sandwiched between positive and negative electrodes. Tiny capsules of black and white pigment float in between and arrange themselves into images and text through variance in the charge (the black are negatively charged and the white positively charged). Since the display is not light-based (like the electronic screens we use today), it has an appearance closer to paper. It can be read in bright sunlight, and requires virtually no power to maintain an image.

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public online chat with Russ Wilcox, the chief exec of E Ink Corp. Wilcox predicts that large e-ink screens will be available within a year or two, opening the door for newspapers to develop an electronic product that combines web and broadsheet. Even offering the screens to subscribers for free, he calculates, would be more cost-efficient than the current paper delivery system.

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public online chat with Russ Wilcox, the chief exec of E Ink Corp. Wilcox predicts that large e-ink screens will be available within a year or two, opening the door for newspapers to develop an electronic product that combines web and broadsheet. Even offering the screens to subscribers for free, he calculates, would be more cost-efficient than the current paper delivery system.

A number of major newspaper conglomerates — including The Hearst Corporation, Gannett Co. (publisher of USA Today), TOPPAN Printing Company of Japan, and France’s Vivendi Universal Publishing — are interested enough in the potential of e-ink that they have become investors.

But maybe it won’t be the storied old broadsheet that people crave. A little over a month ago at a trade show in Berlin, Philips Polymer Vision presented a prototype of its new “Readius” — a device about the size of a mobile phone with a roll-out e-ink screen. This, too, could be available soon. Like it or not, it might make more sense to watch what’s developing with cell phones to get a hint of the future.

But even if electronic paper catches on — and it seems likely that it, or something similar, will — I wouldn’t count on it to solve the problems of the print news industry. It’s often tempting to think of new technologies that fundamentally change the way we operate as simply a matter of pouring old wine into new bottles. But electronic paper will be a technology for delivering the web, or even internet television — not individual newspapers. So then how do we preserve (or transfer) all that is good about print media, about institutions like the Times and the Post, assuming that their prospects continue to worsen? The answer to that, at least for now, is written in invisible ink.