I came across an an interesting overview piece on the future of the book in Global Politician, an online magazine that largely focuses on reporting underreported global issue stories. The author of the piece, economist and political consultant Sam Vaknin, covers much of the terrain we usually cover here at the Institute, but he also make an interesting point about how the online book-swapping collective Bookcrossing has been turning paper books into “networked books” over the past four years. Vaknin writes:

I came across an an interesting overview piece on the future of the book in Global Politician, an online magazine that largely focuses on reporting underreported global issue stories. The author of the piece, economist and political consultant Sam Vaknin, covers much of the terrain we usually cover here at the Institute, but he also make an interesting point about how the online book-swapping collective Bookcrossing has been turning paper books into “networked books” over the past four years. Vaknin writes:

Members of the BookCrossing.com community register their books in a central database, obtain a BCID (BookCrossing ID Number) and then give the book to someone, or simply leave it lying around to be found. The volume’s successive owners provide BookCrossing with their coordinates. This innocuous model subverts the legal concept of ownership and transforms the book from a passive, inert object into a catalyst of human interactions. In other words, it returns the book to its origins: a dialog-provoking time capsule.

I appreciate the fact that Vaknin draws attention to the ways in which books can be conceptually transformed by ventures such as BookCrossing even while they remain physically unchanged. Currently, there are only about half a million BookCrossing members, making the phenemenon somewhat less popular than podcasting, but given that most BookCrossing members are serious readers — and highly international — the movement is still noteworthy.

Category Archives: books

the future of the book: korea, 13th century

The database:

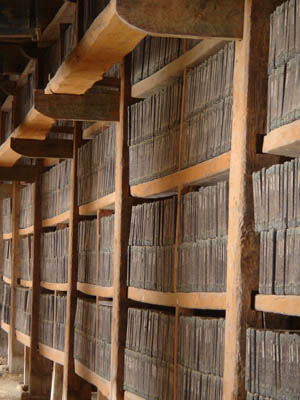

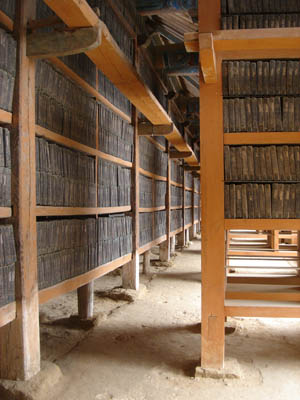

Nestled in the Gaya mountain range in southern Korea, the Haeinsa monastery houses the Tripitaka Koreana, the largest, most complete set of Buddhist scriptures in existence — over 80,000 wooden tablets (enough to print all of Buddhism’s sacred texts) kept in open-air storage for the past six centuries. The tablets were carved between 1237 and 1251 in anticipation of the impending Mongol invasion, both as a spiritual effort to ward off the attack, and as an insurance policy. They replaced an earlier set of blocks that had been destroyed in the last Mongol incursion in 1231.

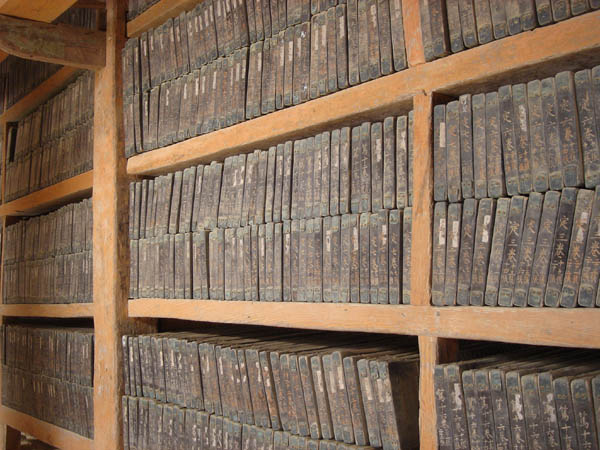

From Korea’s national heritage site description of the tablets:

The printing blocks are some 70cm wide 24cm long and 2.8cm thick on the average. Each block has 23 lines of text, each with 14 characters, on each side. Each block thus has a total of 644 characters on both sides. Some 30 men carved the total 52,382,960 characters in the clean and simple style of Song Chinese master calligrapher Ou-yang Hsun, which was widely favored by the aristocratic elites of Goryeo. The carvers worked with incredible dedication and precision without making a single error. They are said to have knelt down and bowed after carving each character. The script is so uniform from beginning to end that the woodblocks look like the work of one person.

I stayed at the Haeinsa temple last Friday night on a sleeping mat in bare room with a heated floor, alongside a number of noisy Koreans (including the rather sardonic temple webmaster — Haiensa is a Unesco World Heritage site and so keeps a high profile). At three in the morning, at the call to the day’s first service, I tramped around the snowy courtyards under crisp, chill stars and watched as the monks pounded a massive barrel-shaped drum hanging inside a pagoda. This was for the benefit of those praying inside the temple (where it sounds like distant thunder). Shivering to the side, I continued to watch as they rang a bell the size of a Volkswagen with a polished log swung on ropes like a wrecking ball. Next to it, another monk ripped out a loud, clattering drum roll inside the wooden ribs of a dragon-like fish, also suspended from the pagoda’s roof. It was freezing cold with a biting wind — not pleasant to be outside, and at such an hour. But the stars were absolutely vivid. I’m no good at picking out constellations, but Orion was poised unmistakeably above the mountains as though stalking an elk on the other side of the ridge.

It’s a magical, somewhat harsh place, Haiensa. The Changgyeonggak, the two storage halls that house the Tripitaka, were built ingeniously to preserve the tablets by blocking wind, facilitating ventilation and distributing moisture. You see the monks busying themselves with devotions and chores, practicing an ancient way of life founded upon those tablets. The whole monastery a kind of computer, the monks running routines to and from the database. The mountains, Orion, the drum all part of the program. It seemed almost more hi-tech than cutting edge Seoul.

More on that later.

without gods: an experiment

Just in time for the holidays, a little god-free fun…

Just in time for the holidays, a little god-free fun…

The institute is pleased to announce the launch of Without Gods, a new blog by New York University journalism professor and media historian Mitchell Stephens that will serve as a public workshop and forum for the writing of his latest book. Mitch, whose previous works include A History of News and the rise of the image the fall of the word, is in the early stages of writing a narrative history of atheism, to be published in 2007 by Carroll and Graf. The book will tell the story of the human struggle to live without gods, focusing on those individuals, “from Greek philosophers to Romantic poets to formerly Islamic novelists,” who have undertaken the cause of atheism – “a cause that promises no heavenly reward.”

Without Gods will be a place for Mitch to think out loud and begin a substantive exchange with readers. Our hope is that the conversation will be joined, that ideas will be challenged, facts corrected, queries and probes answered; that lively and intelligent discussion will ensue. As Mitch says: “We expect that the book’s acknowledgements will eventually include a number of individuals best known to me by email address.”

Without Gods is the first in a series of blogs the institute is hosting to challenge the traditional relationship between authors and readers, to learn how the network might more directly inform the usually solitary business of authorship. We are interested to see how a partial exposure of the writing process might affect the eventual finished book, and at the same time to gently undermine the notion that a book can ever be entirely finished. We invite you to read Without Gods, to spread the word, and to take part in this experiment.

thinking about google books: tonight at 7 on radio open source

While visiting the Experimental Television Center in upstate New York this past weekend, Lisa found a wonderful relic in a used book shop in Owego, NY — a small, leatherbound volume from 1962 entitled “Computers,” which IBM used to give out as a complimentary item. An introductory note on the opening page reads:

The machines do not think — but they are one of the greatest aids to the men who do think ever invented! Calculations which would take men thousands of hours — sometimes thousands of years — to perform can be handled in moments, freeing scientists, technicians, engineers, businessmen, and strategists to think about using the results.

This echoes Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 essay on computing and networked knowledge, “As We May Think”, which more or less prefigured the internet, web search, and now, the migration of print libraries to the world wide web. Google Book Search opens up fantastic possibilities for research and accessibility, enabling readers to find in seconds what before might have taken them hours, days or weeks. Yet it also promises to transform the very way we conceive of books and libraries, shaking the foundations of major institutions. Will making books searchable online give us more time to think about the results of our research, or will it change the entire way we think? By putting whole books online do we begin the steady process of disintegrating the idea of the book as a bounded whole and not just a sequence of text in a massive database?

The debate thus far has focused too much on the legal ramifications — helped in part by a couple of high-profile lawsuits from authors and publishers — failing to take into consideration the larger cognitive, cultural and institutional questions. Those questions will hopefully be given ample air time tonight on Radio Open Source.

Tune in at 7pm ET on local public radio or stream live over the web. The show will also be available later in the week as a podcast.

sober thoughts on google: privatization and privacy

Siva Vaidhyanathan has written an excellent essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education on the “risky gamble” of Google’s book-scanning project — some of the most measured, carefully considered comments I’ve yet seen on the issue. His concerns are not so much for the authors and publishers that have filed suit (on the contrary, he believes they are likely to benefit from Google’s service), but for the general public and the future of libraries. Outsourcing to a private company the vital task of digitizing collections may prove to have been a grave mistake on the part of Google’s partner libraries. Siva:

The long-term risk of privatization is simple: Companies change and fail. Libraries and universities last…..Libraries should not be relinquishing their core duties to private corporations for the sake of expediency. Whichever side wins in court, we as a culture have lost sight of the ways that human beings, archives, indexes, and institutions interact to generate, preserve, revise, and distribute knowledge. We have become obsessed with seeing everything in the universe as “information” to be linked and ranked. We have focused on quantity and convenience at the expense of the richness and serendipity of the full library experience. We are making a tremendous mistake.

This essay contains in abundance what has largely been missing from the Google books debate: intellectual courage. Vaidhyanathan, an intellectual property scholar and “avowed open-source, open-access advocate,” easily could have gone the predictable route of scolding the copyright conservatives and spreading the Google gospel. But he manages to see the big picture beyond the intellectual property concerns. This is not just about economics, it’s about knowledge and the public interest.

What irks me about the usual debate is that it forces you into a position of either resisting Google or being its apologist. But this fails to get at the real bind we all are in: the fact that Google provides invaluable services and yet is amassing too much power; that a private company is creating a monopoly on public information services. Sooner or later, there is bound to be a conflict of interest. That is where we, the Google-addicted public, are caught. It’s more complicated than hip versus square, or good versus evil.

Here’s another good piece on Google. On Monday, The New York Times ran an editorial by Adam Cohen that nicely lays out the privacy concerns:

Google says it needs the data it keeps to improve its technology, but it is doubtful it needs so much personally identifiable information. Of course, this sort of data is enormously valuable for marketing. The whole idea of “Don’t be evil,” though, is resisting lucrative business opportunities when they are wrong. Google should develop an overarching privacy theory that is as bold as its mission to make the world’s information accessible – one that can become a model for the online world. Google is not necessarily worse than other Internet companies when it comes to privacy. But it should be doing better.

Two graduate students in Stanford in the mid-90s recognized that search engines would the most important tools for dealing with the incredible flood of information that was then beginning to swell, so they started indexing web pages and working on algorithms. But as the company has grown, Google’s admirable-sounding mission statement — “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” — has become its manifest destiny, and “information” can now encompass the most private of territories.

At one point it simply meant search results — the answers to our questions. But now it’s the questions as well. Google is keeping a meticulous record of our clickstreams, piecing together an enormous database of queries, refining its search algorithms and, some say, even building a massive artificial brain (more on that later). What else might they do with all this personal information? To date, all of Google’s services are free, but there may be a hidden cost.

“Don’t be evil” may be the company motto, but with its IPO earlier this year, Google adopted a new ideology: they are now a public corporation. If web advertising (their sole source of revenue) levels off, then investors currently high on $400+ shares will start clamoring for Google to maintain profits. “Don’t be evil to us!” they will cry. And what will Google do then?

images: New York Public Library reading room by Kalloosh via Flickr; archive of the original Google page

world digital library

The Library of Congress has announced plans for the creation of a World Digital Library, “a shared global undertaking” that will make a major chunk of its collection freely available online, along with contributions from other national libraries around the world. From The Washington Post:

The Library of Congress has announced plans for the creation of a World Digital Library, “a shared global undertaking” that will make a major chunk of its collection freely available online, along with contributions from other national libraries around the world. From The Washington Post:

…[the] goal is to bring together materials from the United States and Europe with precious items from Islamic nations stretching from Indonesia through Central and West Africa, as well as important materials from collections in East and South Asia.

Google has stepped forward as the first corporate donor, pledging $3 million to help get operations underway. At this point, there doesn’t appear to be any direct connection to Google’s Book Search program, though Google has been working with LOC to test and refine its book-scanning technology.

online retail influencing libraries

The NY Times reports on new web-based services at university libraries that are incorporating features such as personalized recommendations, browsing histories, and email alerts, the sort of thing developed by online retailers like Amazon and Netflix to recreate some of the experience of browsing a physical store. Remember Ranganathan’s fourth law of library science: “save the time of the reader.” The reader and the customer are perhaps becoming one in the same.

It would be interesting if a social software system were emerging for libraries that allowed students and researchers to work alongside librarians in organizing the stacks. Automated recommendations are just the beginning. I’m talking more about value added by the readers themselves (Amazon has does this with reader reviews, Listmania, and So You’d Like To…). A social card catalogue with a tagging system and other reader-supplied metadata where readers could leave comments and bread crumb trails between books. Each card catalogue entry with its own blog and wiki to create a context for the book. Books are not just surrounded by other volumes on the shelves, they are surrounded by people, other points of view, affinities — the kinds of thing that up to this point were too vaporous to collect. This goes back to David Weinberger’s comment on metadata and Google Book Search.

google print is no more

Not the program, of course, just the name. From now on it is to be known as Google Book Search. “Print” obviously struck a little too close to home with publishers and authors. On the company blog, they explain the shift in emphasis:

No, we don’t think that this new name will change what some folks think about this program. But we do believe it will help a lot of people understand better what we’re doing. We want to make all the world’s books discoverable and searchable online, and we hope this new name will help keep everyone focused on that important goal.

writing in the open

Mitch Stephens, NYU professor, was here for lunch today. when Ben and I met with him about a month ago about the academic bloggers/public intellectuals project, Mitch mentioned he had just signed a contract with Carroll & Graf to write a book on the history of atheism. today’s lunch was to follow up a suggestion we made that he might consider starting a blog to parallel the research and writing of the book. i’m delighted to report that Mitch has enthusiastically taken up the idea. sometime in the next few weeks we’ll launch a new blog, tentatively called Only Sky (shortened from the lyric of john lennon’s Imagine “. . . Above us only sky”). it will be an experiment to see whether blogging can be useful to the process of writing a book. i expect Mitch will be thinking out loud and asking all sorts of interesting questions. i also think that readers will likely provide important insight as well as ask their own fascinating questions which will in turn suggest fruitful directions of inquiry. stay tuned.

the book in the network – masses of metadata

In this weekend’s Boston Globe, David Weinberger delivers the metadata angle on Google Print:

…despite the present focus on who owns the digitized content of books, the more critical battle for readers will be over how we manage the information about that content-information that’s known technically as metadata.

…we’re going to need massive collections of metadata about each book. Some of this metadata will come from the publishers. But much of it will come from users who write reviews, add comments and annotations to the digital text, and draw connections between, for example, chapters in two different books.

As the digital revolution continues, and as we generate more and more ways of organizing and linking books-integrating information from publishers, libraries and, most radically, other readers-all this metadata will not only let us find books, it will provide the context within which we read them.

The book in the network is a barnacled spirit, carrying with it the sum of its various accretions. Each book is also its own library by virtue not only of what it links to itself, but of what its readers are linking to, of what its readers are reading. Each book is also a milk crate of earlier drafts. It carries its versions with it. A lot of weight for something physically weightless.