The following was posted by Gary Frost as a comment to our post on Neil Postman’s “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century.” Gary recently returned from the Mississippi coast where he was part of a team helping to assess library and museum damage after Katrina.

The mystic advise that we walk into the darkness. Postman’s only qualification is that we do futurism with the right gear. But we cannot wander off into the future with enough AA batteries. An archeologist at the storm damaged Jefferson Davis presidential library greeted me saying; “Welcome to the19th century.” He was not kidding. No water, no electricity, no gas, no groceries. He was digging up the same artifacts for the second time in the immense debris fields left by Katrina.

We were driven to a manuscript era and we were invigorated to do our best. Strangely the cell phones worked and we talked to Washington from the 19th century. We asked if the Nation was still interested in the culture of the deep south. Not really, Transformers were at work and in our mobile society the evacuees had left for good. The army trucks were building new roads over the unmarked gravesites of 3000 Confederate veterans, who in their old age, came to Jeff Davis’ home to die.

We were left hanging about the future and technologies were a sidebar. It wasn’t really important that the 19th century had invented instantaneous communication, digital encoding or photographic representation or that the 21st century was taking the credit for its exploitation of these accomplishments. The gist was that the future deserved to be informed and not deluded. The gist was that the future would be fulfilled as a measure of its use of the accomplishments of a much longer past.

Category Archives: book

media consumption #2

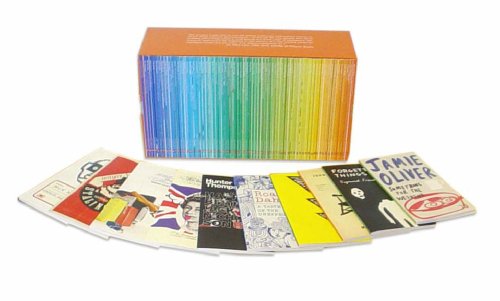

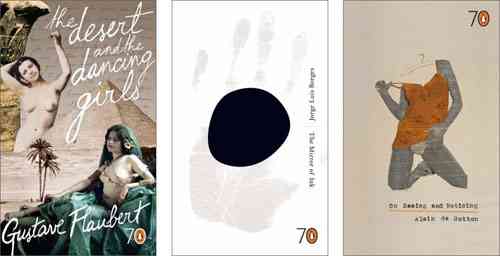

While browsing bookstores in london yesterday — still one of my most favorite pastimes — i came across a beautiful box of 70 thin-spined pocketbooks, the colors of the spine intentionally creating a stunning run of the spectrum from blue to orange. turns out it is a series of 70 essays and short fiction celebrating Penguin’s 70th anniversary and its claim to have initiated the ‘paperback revolution.’ [note: legendary editor jason epstein claims to have done this for Doubleday. does anyone have any insight into whether either claimant really has bragging rights?].

Although i wanted to spring for the whole box, the $125 price tag was too daunting so i bought 3 of the slim volumes — “The Desert and the Dancing Girls,”, a travelogue by Gustave Flaubert describing his journey to Egypt; On Seeing and Noticing,” a collection of philosopher Alain de Botton’s short essays, and “The Mirror of Ink,” seven of Jorge Luis Borge’s wonderful short stories. the cover of each volume is exquisitely and thoughtfully designed, each by a different artist.

Each title is so beautiful in its own right, Penguin has succeeded in putting together a series which underlines the appeal of books as objects. the success of the series stems less from the elegance of the graphic design than from the decision to “go small.” none of the books in the series exceeds 60 pages; given the size of the page and the font, they are probably equivalent to a long piece in the New Yorker or the chapter of a book. had Penguin decided to celebrate their birthday with 70 beautifully designed books i would have wanted to own the objects but wouldn’t necessarily expect to read any of them. however, the curatorial intelligence behind this series seems to have come up with a concept which is “just right.” there is something about the discrete boundaries of these short volumes which makes me think i could read them and that i want to read them, not just own them. the closest analogy is to a box of deliciously appetizing chocolates where i browse the contents over and over, making decsions about which to eat first and which to save for later.

Sad to say i can’t even imagine writing the above to describe offerings in the digital domain. we may get there, but the terms will be different.

(media consumption #1)

yahoo! announces book-scanning project to rival google’s

Yahoo, in collaboration with The Internet Archive, Adobe, O’Reilly Media, Hewlett Packard Labs, the University of California, the University of Toronto, The National Archives of England, and others, will be participating in The Open Content Alliance, a book and media archiving project that will greatly enlarge the body of knowledge available online. At first glance, it appears the program will focus primarily on public domain works, and in the case of copyrighted books, will seek to leverage the Creative Commons.

Google Print, on the other hand, is more self-consciously a marketing program for publishers and authors (although large portions of the public domain will be represented as well). Google aims to make money off its indexing of books through keyword advertising and click-throughs to book vendors. Yahoo throwing its weight behind the “open content” movement seems on the surface to be more of a philanthropic move, but clearly expresses a concern over being outmaneuvered in the search wars. But having this stuff available online is clearly a win for the world at large.

The Alliance was conceived in large part by Brewster Kahle of the Internet Archive. He announced the project on Yahoo’s blog:

To kick this off, Internet Archive will host the material and sometimes helps with digitization, Yahoo will index the content and is also funding the digitization of an initial corpus of American literature collection that the University of California system is selecting, Adobe and HP are helping with the processing software, University of Toronto and O’Reilly are adding books, Prelinger Archives and the National Archives of the UK are adding movies, etc. We hope to add more institutions and fine tune the principles of working together.

Initial digitized material will be available by the end of the year.

More in:

NY Times

Chronicle of Higher Ed.

creative versioning project

“I don’t have a single early draft of any novel or story. I just ‘saved’ over the originals until I reached the final version. All there is is the books themselves.” – Zadie Smith

This is a call (re-published from the Electronic Literature Organization) for writers to participate in a creative versioning project, hopefully to begin this winter:

Matthew Kirschenbaum is looking for poets and fiction writers willing to participate in a project to archive versions of texts in progress. An electronic document repository (known as a Concurrent Versions System, or CVS) will be used to track revisions and changes to original fiction and poetry contributed by participating writers who will work by checking their drafts in and out of the repository system. The goal is to provide access to a work at each and every state of its composition and conceptual evolution — thereby capturing the text as a living, dynamic object-in-the-making rather than a finished end-product. A reader will be able to watch the composition process unfold as though s/he were looking over the writer’s shoulder.

For guidelines and contact info, visit ELO.

kurzweil’s techno-narcissism

Ray Kurzweil looks into the future and sees the singularity gazing back full of love. It whispers. It seduces. “Ray, take care. Preserve yourself. It will be another 50 years yet. Go. Preserve yourself with vitamins, fruits, infusions. Keep your body tender and vital, and soon enough you will be subsumed, you will transcend. The singularity is near!”

Kurzweil’s book is out and it’s as big as a dictionary. A good friend of mine was given it as a gift a couple of nights ago for his birthday. After dinner, as we rode the crosstown bus toward a game of cards, I read the first few pages. Try holding this goliath in one hand! The bus was crowded and we were standing in the aisle, gripping the handles on the top rail. The bus lurched, and I cursed my physiognomy. If only I could download the damn thing into my brain! If only the singularity were here now!

Kurzweil’s book is out and it’s as big as a dictionary. A good friend of mine was given it as a gift a couple of nights ago for his birthday. After dinner, as we rode the crosstown bus toward a game of cards, I read the first few pages. Try holding this goliath in one hand! The bus was crowded and we were standing in the aisle, gripping the handles on the top rail. The bus lurched, and I cursed my physiognomy. If only I could download the damn thing into my brain! If only the singularity were here now!

Kurzweil’s theory, or rather, his unshakeable conviction, his messianic belief, is that we, the human species, are nearing the point (he predicts around 2045) when our tools will become more intelligent than us and we will merge – mentally, biologically, spiritually – with them. Computer processing, artificial intelligence, biotechnology are all developing at an exponential rate (the law of accelerating returns), and are approaching a point of singularity, an all-encompassing transformative power, that will enable us to eliminate poverty, eradicate hunger, and “transcend biology.”

The reason Kurzweil is preserving his body – “reprogramming his biochemistry,” as he puts it – is because he is convinced that in about a generation’s time we will be able to ingest millions of microscopic nanobots into our neural pathways that will turn our brains into supercomputers, and engineer ourselves to live as long as we please. We will become, to borrow a conceit from an earlier book of Kurzweil’s, “spiritual machines.”

I would like to say that I will take the time to read his book and engage with it in more than a passing (and admittedly reactionary) way. Perhaps we’ll make a project of reading Kurzweil here at the institute as a counterpoint to Neil Postman (see recent discussion). But I’m not sure how much of his flaming narcissism I can take. Kurzweil’s ideas of “transhumanism” are so divorced from any social context, so devoid of any acknowledgment of the destructive or enslaving capacities of technology, and above all, so self-involved (the fruit and vitamin regimen is no joke – and there is probably a black monolith at the foot of his bed), that I’m not quite sure how to have a useful discussion about them.

As an inventor, Kurzweil has made many valuable contributions to society, including text-to-speech synthesis and speech recognition technology that has greatly aided the blind. It is understandable that his success in these endeavors has instilled a certain faith in technology’s capacity to do good. But his ecstatic, almost sexual, enthusiasm for human-machine integration is more than a little grotesque. Kurzweil’s website and book jacket are splashed with approving quotes from big name technologists. But I don’t find it particularly reassuring, or convincing, to know that Bill Gates thinks

Ray Kurzweil is the best person I know at predicting the future of artificial intelligence.

For a more reasoned, economic analysis of the possible outcomes of accelerating returns, read John Quiggins’ “The singularity and the knife-edge” on Crooked Timber. Another law – or if not a law, then at least a common sense suspicion – is that if the engine keeps accelerating and heating it up, it will eventually fall apart.

the future of the institute

lately i’ve been thinking about how the institute for the future of the book should be experimental in form as well as content – an organization whose work, when appropriate, is carried out in real time in a relatively public forum. one of the key themes of our first year has been the way a network adds value to an enterprise, whether that be a thought experiment, an attempt to create a collective memory, a curated archive of best practices, or a blog that gathers and processes the world around it. i sense we are feeling our way to new methods of organizing work and distributing the results, and i want to figure out ways to make that aspect of our effort more transparent, more available to the world. this probably calls for a reevaluation of (or a re-acquaintance with) our idea of what an institute actually is, or should be.

the university-based institute arose in the age of print. scholars gathering together to make headway in a particular area of inquiry wrote papers, edited journals, held symposia and printed books of the proceedings. if books are what humans have used to move big ideas around, institutes arose to focus attention on particular big ideas and to distribute the result of that attention, mostly via print. now, as the medium shifts from printed page to networked screen, the organization and methods of “institutes” will change as well.

how they will change is what we hope to find out, and in some small way, influence. so over the next year or so we’ll be trying out a variety of different approaches to presenting our work, and new ways of facilitating debate and discussion. hopefully, we’ll draw some of you in along the way.

here’s a first try. we’ve decided (see thinking out loud) to initiate a weekly discussion at the institute where we read a book (or article or….) and then have a no-holds discussion about it — hoping to at least begin to understand some of the first order questions about what we are doing and how it fits into our perspectives on society. mostly we’re hoping to get to a place where we are regularly asking these questions in our work (whether designing software, studying the web, holding a symposium, or encouraging new publishing projects), measuring technological developments against a sense of what kind of society we’d like to live in and how a particular technology might help or hinder our getting there.

the first discussion is focused on neil postman’s “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century.” following is the audio we recorded broken into annotated chapters. we would be interested in getting people’s feedback on both form and content. (jump to the discussion)

podcast: discussing neil postman’s “building a bridge to the 18th century”

(Annotated audio recordings of this discussion appear further down.)

(Annotated audio recordings of this discussion appear further down.)

On the dedication page of “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century,” Neil Postman quotes the poet Randall Jarrell:

Soon we shall know everything the 18th century didn’t know, and nothing it did, and it will be hard to live with us.

Though often failing to provide satisfying answers, Postman asks the kind of first-order questions one hears all too infrequently at a time when technology’s impact on our social, political and intellectual lives grows ever more profound. Postman has been accused of deep reactionism toward technology, and indeed, his hostility toward computers and telecommunications betrays an elitism that discredits some of his larger, and quite compelling observations.

In spite of this, Postman’s diagnosis is persuasive: that the idea of technological progress bequeathed by the Enlightenment has detached from reason and become a runaway train, that we are unquestioningly embracing new technologies that unleash massive change on our family and communal life, our democracy, and our capacity to think critically. We have stopped asking the single most important question that should be applied to all new technological innovations: does this technology solve a problem? If so, then at what cost? To whose benefit? And at whose expense?

Postman portrays the contemporary West as a culture without a narrative, littered with the shards of broken ideologies – depressed, unmotivated, and therefore uncritical of the new technologies that are foisted upon it by a rapacious capitalist system. The culprit, as he sees it, is postmodernism, which he lambasts (rather simplistically) as a corrosive intellectual trend, picking at the corpse of the Enlightenment, and instilling torpor and malaise at all levels of culture through its distrust of language and dogged refusal to accept one truth over another. This kind of thinking, Postman argues, is seductive, but it starves humans of their inspiration and sense of purpose.

To be saved, he goes on, and to build a better future, we would do well to look back to the philosophes of 18th century Europe, who, in the face of surging industrialization, defined a new idea of universal rational humanism – one that allowed for various interpretations within its fold, was rigorously suspicious of religious or any other kind of dogma, and yet gave the world a sense of moral uplift and progress. Postman does not suggest that we copy the 18th century, but rather give it careful study in order to draw inspiration for a new positive narrative, and for a reinvigoration of our critical outlook. This, Postman insists, offers us the best chance of surviving our future.

Postman’s note of alarm, if at times shrill, is nonetheless a refreshing antidote to the techno-optimism that pervades contemporary culture. And his recognition of our “crisis in narrative” – a formulation borrowed from Vaclav Havel – is dead on.

September 19: Bob, Dan, Kim, and Ben discuss Postman’s book at our new Brooklyn office (special prize if you pick out the sound of the ice cream truck passing by).

1. Bob’s preface – thoughts about how we do business at the institute (1:56) (download)

2. Ben’s first impressions – childhood under threat… Dan’s first impressions into discussion – a Clinton-era book, sets up a rather straw man caricature with the postmodernists, but society’s need for a narrative is compelling – why the Christian right has done so well… Postman seems to be assuming that progress is a law, that there is a directed narrative to history – problems with how he treats evolution. (6:43) (download)

3. Bob: Postman is much better at identifying problems than at coming up with solutions. Which is what makes him compelling. His stance is courageous. People assume with technology that just because something can be done it should be done. This is a tremendous problem – an affliction. If you could go back in time and be the inventor of the automobile, would you do it? People get angry at the responsibility this question imputes to them. How can we put these big questions at the center of our work? (13:34) (download)

4. Another big question… “An electronic community is only a simulation of a real community”? Flickr, Friendster, Howard Dean campaign? What is the vehicle for talking about this? What format is best for engaging these questions? Looking for new forms that illuminate or activate the questions. (15:43) (download)

5. Where/who are the public intellectuals today? [The ice cream truck passes by.] Strange bifurcation of the intellectual elite – many of the best-educated people most able to deal with abstraction make their living producing popular media that controls society. (10:07) (download)

6. Is capitalism the problem? Postman’s bias: written language will never be surpassed in its power to deal with abstract thought and cultivation of ideas. But we are arguably past the primacy of print. What is our attitude toward this? (9:39) (download)

7. What opportunities for reflection do different media afford? Films on DVD can be read and reread like a book – the viewer controls, rather than being controlled – a possibility for reflection not available in broadcast. What is the proper venue for discussing this? Capitalism is the 800 lb. gorilla in the room. How do we create, if not a mass agitation, then at least a mass discussion? Tie it to the larger pressing problems of the world and how they will be better addressed by certain forms of discourse and reflection. Averting ecological catastrophe as one possible narrative – an inspiring motivator that will get people moving. How do find our way back into history? (10:09) (download)

8. What should we read next as counterpoint/antidote to Postman? The Matrix – are we headed that way? (12:33) (download)

9. How do we organize new kinds of debates about technology and society? Other issues to be addressed – class, race and gender inequality. (11:26) (download)

a book is not a text: the noise made by people

Momus – a.k.a. Nick Currie, electronic folk musician, Wired columnist, and inveterate blogger – has posted an interesting short video on his blog, Click Opera. He’s teaching a class on electronic music composition & narrative for Benneton’s Fabrica in Venice. His video encourages students to listen for the environmental sounds that they can make with electronic instruments: not the sounds that they’re designed to make, but the incidental noises that they make – the clicking of keys on a Powerbook, for example – that we usually ignore as being just that, incidental. We ignore the fact that these noises are made directly by people, without the machine’s intercession.

Momus’s remarks put me in mind of something said by Jerome McGann at the Transliteracies conference in Santa Barbara last June – maybe the most important thing that was said at the conference, even if it didn’t warrant much attention at the time. What we tend to forget when talking about reading, he said, was that books – even regular old print books – are full of metadata. (Everybody was talking about metadata in June, like they were talking about XML a couple of years ago – it was the buzzword that everyone knew they needed to have an opinion about. If not, they swung the word about feverishly in the hopes of hitting something.) McGann qualified his remarks by referring to Ezra Pound’s idea of melopoeia, phanopoeia, and logopoeia – specific qualities in language that make it evocative:

. . . you can still charge words with meaning mainly in three ways, called phanopoeia, melopoeia, logopoeia. You can use a word to throw a visual image on to the reader’s imagination, or you charge it by sound, or you use groups of words to do this.

(The ABC of Reading, p.37) In other words, words aren’t always just words: when used well, they refer beyond themselves. This process of referring, McGann was claiming, is a sort of metadata, even if technologists don’t think about it this way: the way in which words are used provides the attuned reader with information about their composition beyond the meaning of the words themselves.

But thinking about McGann’s comments in terms of book design might suggest wider implications for the future of the book. Let’s take a quick excursion to the past of the book. Once it was true that you couldn’t judge a book by its cover. Fifty years ago, master book designer Jan Tschichold opined about book jackets:

A jacket is not an actual part of the book. The essential portion is the inner book, the block of pages . . . [U]nless he is a collector of book jackets as samples of graphic art, the genuine reader discards it before he begins.

(“Jacket and Wrapper,” in The Form of the Book: Essays on the Morality of Good Design) Tschichold’s statement seems bizarre today: nobody throws away book jackets, especially not collectors. Why? Because today we take it for granted that we judge books by their covers. The cover has been subsumed into our idea of the book: it’s a signifying part of the book. By looking at a cover, you, the prospective book-buyer, can immediately tell if a recently-published piece of fiction is meant to be capital-L Literature, Nora Roberts-style fluff, or somewhere in between. Contextual details like the cover are increasingly important.

Where does the electronic book fit into this, if at all? Apologists for the electronic book are constantly about the need for an ideal device as the be-all and end-all: when we have e-Ink or e-Paper and a well-designed device which can be unrolled like a scroll, electronic books will suddenly take off. This isn’t true, and I think it has something to do with the way people read books, something that hasn’t been taken into account by soi-disant futurists, and something like what Jerome McGann was gesturing at. A book is not a text. It’s more than a text. It’s a text and a collection of information around that text, some of which we consciously recognize and some of which we don’t.

A few days ago, I excoriated Project Gutenberg’s version of Tristram Shandy. This is why: a library of texts is not the same thing as a library of books. A quick example: download, if you wish, the plain text or HTML version of Tristram Shandy, which you can get here. Look at the opening pages of the HTML version. Recognizing that this particular book needs to be more than plain old seven-bit ASCII, they’ve included scans of the engravings that appear in the book (some by William Hogarth, like this; a nice explication of this quality of the book can be found here). What’s interesting to me about these illustrations that Project Gutenberg is how poorly done these are. These are – let’s not beat around the bush – bad scans. The contrast is off; things that should be square look rectangular. The Greek on the title page is illegible.

Let’s go back to Momus listening to the unintentional noises made by humans using machines: what we have here is the debris of another noisy computer, the noise of a key that we weren’t supposed to notice. Something about the way these scans is dated in a very particular way – half of the internet looked like this in 1997, before everyone learned to use Photoshop properly. Which is when, in fact, this particular document was constructed. In this ugliness we have, unintentionally, humanity. John Ruskin (not a name often conjured with when talking about the future) declared that one of the hallmarks of the Gothic as an architectural style was a perceived “savageness”: it was not smoothed off like his Victorian contemporaries would have liked. But “savageness”, for him, was no reproach: instead, it was a trace of the labor that went into it, a trace of the work’s humanity. Perfection, for him, was inhumane: humanity

. . . was not intended to work with the accuracy of tools, to be precise and perfect in all their actions. If you will have that precision out of them, and make their fingers measure degrees like cog-wheels, and their arms strike curves like compasses, you must unhumanize them . .

(The Stones of Venice) What we have here is, I think, something similar. While Project Gutenberg is probably ashamed of the quality of these graphics, there’s something to be appreciated here. This is a text on its way to becoming a book; it unintentionally reveals its human origins, the labor of the anonymous worker who scanned in the illustrations. It’s a step in the right direction, but there’s a great distance still to go.

marketing books on mobile phones

Harper Collins Australia’s new MobileReader service beams information about new titles and authors, and even book excerpts, to a cellphone. They’re beginning with promotions of Dean Koontz, Paul Coelho and others.

(via textually)

“the minotaur project” featured at ELO

Kim’s hypermedia poem cluster, “The Minotaur Project,” is currently featured at the Electronic Literature Organization. Highly recommended.