I went to Paris last weekend. I have a friend there with an apartment, flights are cheap in the off season, and I’ve never been there before. As might have been expected, I learned absolutely nothing about France. But I did come away with a lot of food for thought about America – specifically, how books work in the United States. Says Gilles Deleuze: “travel does not connect places, but affirms only their difference.” He’s right: sometimes you needs to get away from a place to think about it.

Three observations, then, on how books work in the United States w/r/t my French observations. This post is perhaps less liberal in its interpretation of books than we usually are around here: bear with me for a bit, there’s still plenty of rampant generalizing.

* * * * *

Wandering around the Sorbonne, my friend & I came upon the Librerie Philosophique J. Vrin and went in. It’s a good-sized bookshop that’s devoted entirely to used and new philosophy books, mostly in French, although the neatly categorized shelves are noticeably peppered with other languages. On the Saturday evening I was there, it was full of browsing customers: it’s obviously a working bookstore. We don’t have philosophy book stores in the U.S. One finds, of course, no end of religious bookstores, but unless I’m tremendously mistaken, there’s none dedicated solely to philosophy. (And as far as I know, there’s only one poetry bookstore remaining in the U.S.)

It’s a(n admittedly minor) shock to find oneself in a philosophy bookstore. But a deeper question tugs at me: why aren’t there philosophy book stores in the United States? I’m certainly not qualified to judge what the existence of J. Vrin says about France, but its lack of an analogue in the U.S. clearly says something (besides the obvious “the market won’t support it”). Are we not thinking about big ideas and shipping them about in books? Are the only people who need to read Plato our neocon overlords? Why don’t we need books like these?

* * * * *

Another thing you notice at J. Vrin, as well as elsewhere in Paris: how monotone the books are. It’s not quite a color-coordinated bookstore but it’s close: just about every spine is white, a smaller number being yellow, a smattering of other colors. If you pull a book out, the cover designs are mostly in a classic French style: lots of space, Didot type, some discreet flourishes. These two are typical:

I’m not tremendously interested in French book style of itself, though: I’m more interested in what this minimalist tendency reveals about American book design and the ideas behind it. A trio of comparisons: the French on the left of each pair, the American on the right:

The American covers seem more designed – not necessarily better designed, that goes both ways – but they clearly exist as marketing. The French book covers aren’t advertising in the same way that the American book covers are. The implication here seems to be that French books are for reading, rather than for looking at. Nobody’s going to pick up one of those because of the way the cover looks. It’s presumed that the reader is already interested in the content of the book; what’s on the cover won’t change that interest. There’s a lot more variety in the American books: I might be persuaded to pick up the Deleuze book on Proust (where the quotation above came from) because it looks nice, or dissuaded from picking up the Amélie Nothomb book because it looks so horrible & the title was mangled into something out of Crate & Barrel.

There’s an essay by Jan Tschichold, the doyen of modern book design, advising the reader that the jacket of a hardcover book should be taken off and thrown away as soon as you get the book home. This seems heretical to a book collector (or designer), but I think his point ultimately makes sense: books shouldn’t exist as art objects, they exist to be read. Design should focus attention on, not deflect attention from, the ideas in the book. American book design has drifted away from that precept. (Tschichold, were he still alive, might argue that it’s failed entirely: that essay appears in a book titled The Form of the Book: Essays on the Morality of Good Design which has hardened into an art object: get a used copy for $102.50.)

There’s an essay by Jan Tschichold, the doyen of modern book design, advising the reader that the jacket of a hardcover book should be taken off and thrown away as soon as you get the book home. This seems heretical to a book collector (or designer), but I think his point ultimately makes sense: books shouldn’t exist as art objects, they exist to be read. Design should focus attention on, not deflect attention from, the ideas in the book. American book design has drifted away from that precept. (Tschichold, were he still alive, might argue that it’s failed entirely: that essay appears in a book titled The Form of the Book: Essays on the Morality of Good Design which has hardened into an art object: get a used copy for $102.50.)

Probably I didn’t need to go to France to figure this out: scrutinizing the Spanish and Bangla bookshops and bookcarts in my neighborhood reveals book covers that are closer to French than American design.

* * * * *

Back to advertising: in the windows of wine bars, one sees volumes of Deleuze and Julia Kristeva, not exactly what we usually construe as light café reading. These books are cultural signifiers: presumably the right sort of passersby see them and understand that the winebar is the right sort of place for people like them. Could you do this in the U.S.? You could; by putting Stanley Cavell and Peter Singer in the window, I suspect that you’d attract a lot of confusion and maybe, if you were lucky, some shabby grad students. In Paris: pretty people. (Are they actually interested in Kristeva and Deleuze, or are they just interested in the wine? Again: no idea.)

It’s worth pointing out that Paris didn’t seem technologically reactionary to me: books haven’t succeeded at the expense of newer media. Paris is full of wireless, for example, and URLs are splattered all over advertisements. If anything, books seem to have succeeded with new media: a casual flip through the enormous number of channels on my friend’s television yielded a couple of book review programs. Again: books are part of the cultural discourse there in a way that isn’t the case here.

* * * * *

I haven’t mentioned snobbery yet, though that’s obviously an essential part of this discourse. No one imagines that the majority of the French care that much about Derrida, and it’s clear the French have their own problems which don’t need my interpretations. And more importantly: it would be foolish to jump to the conclusion that America is anti-literary. I’m reminded of the bit in Proust’s Time Regained where the Baron de Charlus, equally drawn to both sides in WWI, declares himself pro-German because he’s surrounded by people parroting pro-French platitudes and he can’t stand them. I won’t deny that there’s a little bit of Charlus in my stance. But I do think that the lens of snobbery can be a useful way to scrutinize how cultural capital works, and this analysis can be broadened to look at the sort of big-picture questions we’re interested in at the Institute. Nor am I the only one who’s noticed this: a better analysis than my own can be found in Pascale Casanova’s The World Republic of Letters (depicted above in both French and American editions), a book from a few years ago:

. . . New York and London cannot be said to have replaced Paris in the structure of literary power: one can only note that, as a result of the generalization of the Anglo-American model and the growing influence of financial considerations, these two capitals tend to acquire more and more power in the literary world. But one must not oversimplify the situation by applying a political analysis that opposes Paris to New York and London, or France to the United States.”

(p. 168.) Casanova’s book is a nice (and readable) study of how literature functions globally as cultural capital; this review by William Deresiewicz in The Nation is a serviceable introduction. It’s a useful text for thinking about how big ideas have historically been “legitimated” (her term) and disseminated. Along the way, she can’t help but make a strong case for Paris being the historic arbiter of much of the world’s taste: Joyce, Faulkner, Borges, Wiesel (a list which could be extended at length) all first came to global prominence through French interest.

Another reminder that things are different in different countries: earlier this week, Pedro Meyer, the Mexican photographer who runs ZoneZero had a long lunch with the Institute, where he reiterated that the way books function in the U.S. is not necessarily the way they function in Latin America, where books are much scarcer and bookshops generally nonexistent. Meyer’s concerns echo those of Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe who blisters at American critics arguing that African novels are universal, only with different names:

“Does it ever occur to these [academics] to try out their game of changing names of characters and places in an American novel, say, a Philip Roth or an Updike, and slotting in African names just to see how it works? But of course it would not occur to them. It would never occur to them to doubt the universality of their own literature. In the nature of things the work of a Western writer is automatically informed by universality. It is only others who must strain to achieve it . . . I should like to see the word ‘universal’ banned altogether from discussions of African literature until such time as people cease to use it as a synonym for the narrow, self-serving parochialism of Europe, until their horizon extends to include all the world.”

(p. 156 in Casanova.) Culture cuts both ways. It’s important to remember that the ways books (and, by extension, their electronic analogues) function in American society isn’t the only way they can or should function. We tend to fall into the assumption that there is no alternative to the way we live. This is myopia, a myopia we need to continually recognize.

I was lucky enough to have a chance to be at The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom book launch at Eyebeam in NYC last week. After a short introduction by Jonah Peretti, Yochai Benkler got up and gave us his presentation. The talk was really interesting, covering the basic ideas in his book and delivered with the energy and clarity of a true believer. We are, he says, in a transitional period, during which we have the opportunity to shape our information culture and policies, and thereby the future of our society. From the introduction:

I was lucky enough to have a chance to be at The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom book launch at Eyebeam in NYC last week. After a short introduction by Jonah Peretti, Yochai Benkler got up and gave us his presentation. The talk was really interesting, covering the basic ideas in his book and delivered with the energy and clarity of a true believer. We are, he says, in a transitional period, during which we have the opportunity to shape our information culture and policies, and thereby the future of our society. From the introduction:

I came across an an interesting overview piece on

I came across an an interesting overview piece on

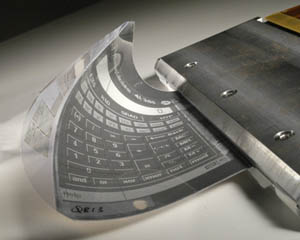

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year). Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

As for the device, well, the

As for the device, well, the