The notion of expert review has been tossed around in the open-content community for a long time. Philosophically, those who lean towards openness tend to sneer at the idea of formalized expert review, trusting in the multiplied consciousness of the community to maintain high standards through less formal processes. Wikipedia is obviously the most successful project in this mode.The informal process has the benefit of speed, and avoids bureaucracy—something which raises the barrier to entry, and keeps out people who just don’t have the time to deal with ‘process.’

The other side of that coin is the belief that experts and editors encourage civil discourse at a high level; without them you’ll end up with mob rule and lowest common denominator content. Editors encourage higher quality writing and thinking. Thinking and writing better than others is, in a way, the definition of expert. In addition, editors and experts tend to have a professional interest in the subject matter, as well as access to better resources. These are exactly the kind of people who are not discouraged by higher barriers to entry, and they are, by extension, the people that you want to create content on your site.

Larry Sanger thinks that, anyway. A Wikipedia co-founder, he gave an interview on news.com about a project that plans to create a better Wikipedia, using a combination of open content development and editorial review: The Digital Universe.

You can think of the Digital Universe as a set of portals, each defined by a topic, such as the planet Mars. And from each portal, there will be links to the best resources on the Web, including a lot of resources of different kinds that are prepared by experts and the general public under the management of experts. This will include an encyclopedia, as well as public domain books, participatory journalism, forums of various kinds and so forth. We’ll build a community of experts and an online collaborative network of independent organizations, each of which has authority over its own discipline to select material and to build resources that are together displayed through a single free-information platform.

I have experience with the editor model from my time at About.com. The About.com model is based on ‘guides’—nominal (and sometimes actual) experts on a chosen topic (say NASCAR, or anesthesiology)—who scour the internet, find good resources, and write articles and newsletters to facilitate understanding and keep communities up to date. The guides were overseen by a bevy of editors, who tended mostly to enforce the quotas for newsletters and set the line on quality. About.com has its problems, but it was novel and successful during its time.

The Digital Universe model is an improvement on the single guide model; it encourages a multitude of people to contribute to a reservoir of content. Measured by available resources, the Digital Universe model wins, hands down. As with all large, open systems, emergent behaviors will add even more to the system in ways than we cannot predict. The Digitial Universe will have it’s own identity and quality, which, according to the blueprint, will be further enhanced by expert editors, shaping the development of a topic and polishing it to a high gloss.

Full disclosure: I find the idea of experts “managing the public” somehow distasteful, but I am compelled by the argument that this will bring about a better product. Sanger’s essay on eliminating anti-elitism from Wikipedia clearly demonstrates his belief in the ‘expert’ methodology. I am willing to go along, mindful that we should be creating material that not only leads people to the best resources, but also allows them to engage more critically with the content. This is what experts do best. However, I’m pessimistic about experts mixing it up with the public. There are strong, and as I see it, opposing forces in play: an expert’s reputation vs. public participation, industry cant vs. plain speech, and one expert opinion vs. another.

The difference between Wikipedia and the Digital Universe comes down, fundamentally, to the importance placed on authority. We’ll see what shape the Digital Universe takes as the stresses of maintaining an authoritative process clashes with the anarchy of the online public. I think we’ll see that adopting authority as your rallying cry is a volatile position in a world of empowered authorship and a universe of alternative viewpoints.

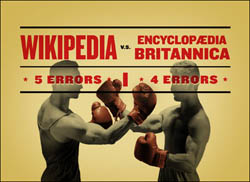

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did

A new and fairly authoritative voice has entered the Wikipedia debate: last week, staff members of the science magazine Nature read through a series of science articles in both Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica, and decided that Britannica — the “gold standard” of reference, as they put it — might not be that much more reliable (we did