The Tate Triennial 2006, showcasing new British Art, brings together thirty-six artists who explore the reuse and reshaping of cultural material. Curated by Beatrix Ruf, director of the Kunsthalle in Zurich, the exhibition includes artists from different generations who explore reprocessing and repetition through painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, film, installations and live work.

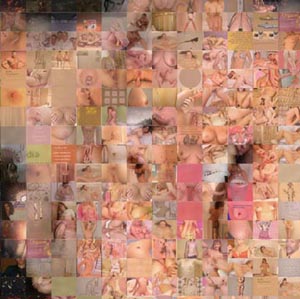

Historically, the appropriation of images and other cultural matter has been practiced by societies as the reiteration, reshuffling, and eventual transformation of artistic and intellectual human manifestations. It covers a vast range from tribute to pastiche. When visual codes are combined, the end product is either a cohesive whole where influences connect into new and very personal languages, or disparate combinations where influences compete and clash. In today’s art, the different guises of repetition, from collage and montage to file sharing and digital reproduction highlight the existing codes or reveal the artificiality of the object. Today’s combination of codes alludes to a collective sense of memory in a moment when memories have become literally photographic.

One comes out of this exhibition thinking about Duchamp‘s “readymades,” Rauschenberg’s “combines,” and other forms of conceptual “gluing,” (the literal meaning of the word “collage,”) as precursors and/or manifestations of the postmodern condition. This show is a perfect representation of our moment. As Beatrix Ruf says in the catalogue: “Artists today are forging new ways of making sense of reality, reworking ideas of authenticity, directness and social relevance, looking again into art practices that emerged in the previous century.”

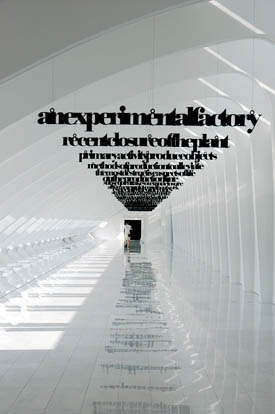

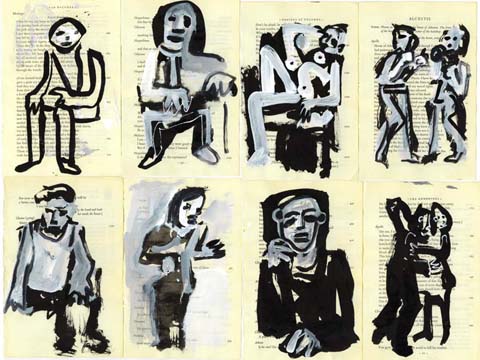

We have artists like Michael Fullerton, who paints contemporary figures in the style of Gainsborough, or Luke Fowler‘s use of archive material to explore the history of Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra. Repetition goes beyond inter-referentiality in the work of Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who combines works he made in the 70s with projected images of himself as a young man and as an adult, within a space where a vase of flowers set on a Marcel Breuer’ table and a pendulum swinging back and forth position the images of the past solidly in the present. In “Twelve Angry Women,” Jonathan Monk affixes to the wall twelve found drawings by an unknown artist from the 20s, using different colored pins that work as earrings. Mark Leckey uses Jeff Koons’ silver bunny as a mirror into his studio in the way 17th century masters painted theirs. Liam Gillick creates sculptures of hanging texts made out of factory signage.

Art itself is cumulative. Different generations build upon previous ones in a game of action and reaction. One interesting development in art today is the collective. Groups of artists coming together in couples, teams, or cyberspace communities, sometimes under the identity of a single person, sometimes a single person assuming a multiple identity. Collectives seem to be a new phenomenon, but their roots go back to the concept of workshops in antiquity where artistic collaboration and copying from casts of sculptural masterpieces was the norm. The notion of the individual artist producing radically new and original art belongs to modernity. The return to collectives in the second part of the 20th century, and again now, has a lot to do with the nature of representation, with the desire to go beyond the limits of artistic mimesis or individual interpretation.

On the other hand, appropriation as a form of artistic expression is a postmodern phenomenon. Appropriation is the language of today. Never before the advent of the Internet had people appropriated knowledge, spaces, concepts, and images as we do today. To cite, to copy, to remix, to modify are part of our everyday communication. The difference between appropriation in the 70s and 80s and today resides in the historical moment. As Jean Verwoert says in the Triennial 2006 catalogue:

The standstill of history at the height of the Cold War had, in a sense, collapsed the temporal axis and narrowed the historical horizon to the timeless presence of material culture, a presence that was exacerbated by the imminent prospect that the bomb could wipe everything out at any time. To appropriate the fetishes of material culture, then, is like looting empty shops at the eve of destruction. It is the final party before doomsday. Today, on the contrary, the temporal axis has sprung up again, but this time a whole series of temporal axes cross global space at irregular intervals. Historical time is again of the essence, but this historical time is not the linear or unified timeline of steady progress imagined by modernity: it is a multitude of competing and overlapping temporalities born from the local conflicts that the unresolved predicaments of the modern regimes still produce.

Today, the challenge is to rethink the meaning of appropriation in a moment when capitalist commodity culture has become the determinant of our daily lives. The Internet is perhaps our potential Utopia (though “dystopian” seems to be the adjective of choice now.) But, can it be called upon to fulfill the unfulfilled promises of 20th century’s utopias? To appropriate is to resist the notion of ownership, to appropriate the products of today’s culture is to expose the unresolved questions of a world shaped by the information era. The disparities between those who are entering the technology era and those forced to stay in the times of early industrialization are more pronounced than ever. As opposed to the Cold War, where history was at a standstill, we live in a time of extreme historicity. Permanence is constantly challenged, how to grasp it all continues to be the elusive task.

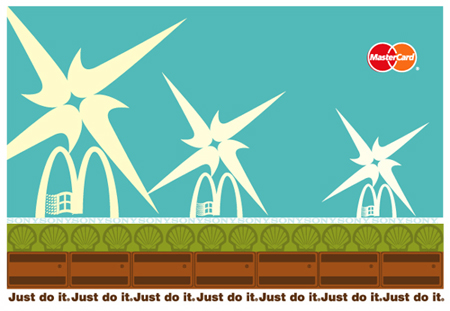

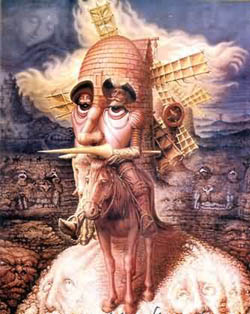

Pedro Meyer’s

Pedro Meyer’s

Se reunen creadores tan disímiles como William Burroughs y Adbusters, cuyo contexto comun sería precisamente la idea de romper, de volver trizas, que está en el seno mismo del verbo “to bust”. Al descontextualizar lo que se quiere romper, se le roba permanencia como ícono estático y se le confiere nueva vida dentro de un nuevo contexto.

Se reunen creadores tan disímiles como William Burroughs y Adbusters, cuyo contexto comun sería precisamente la idea de romper, de volver trizas, que está en el seno mismo del verbo “to bust”. Al descontextualizar lo que se quiere romper, se le roba permanencia como ícono estático y se le confiere nueva vida dentro de un nuevo contexto.

“

“