The Internet Archive has just established an archive dedicated to preserving the online response to the Katrina catastrophe. According to the Archive:

The Internet Archive and many individual contributors worked together to put together a comprehensive list of websites to create a historical record of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina and the massive relief effort which followed. This collection has over 25 million unique pages, all text searchable, from over 1500 sites. The web archive commenced on September 4th.

If you try to link to the Internet Archive today, you might not get through, because everyone is on the site talking about the Grateful Dead’s decision to allow free downloading

Category Archives: archive

welcome to the 19th century

The following was posted by Gary Frost as a comment to our post on Neil Postman’s “Building a Bridge to the 18th Century.” Gary recently returned from the Mississippi coast where he was part of a team helping to assess library and museum damage after Katrina.

The mystic advise that we walk into the darkness. Postman’s only qualification is that we do futurism with the right gear. But we cannot wander off into the future with enough AA batteries. An archeologist at the storm damaged Jefferson Davis presidential library greeted me saying; “Welcome to the19th century.” He was not kidding. No water, no electricity, no gas, no groceries. He was digging up the same artifacts for the second time in the immense debris fields left by Katrina.

We were driven to a manuscript era and we were invigorated to do our best. Strangely the cell phones worked and we talked to Washington from the 19th century. We asked if the Nation was still interested in the culture of the deep south. Not really, Transformers were at work and in our mobile society the evacuees had left for good. The army trucks were building new roads over the unmarked gravesites of 3000 Confederate veterans, who in their old age, came to Jeff Davis’ home to die.

We were left hanging about the future and technologies were a sidebar. It wasn’t really important that the 19th century had invented instantaneous communication, digital encoding or photographic representation or that the 21st century was taking the credit for its exploitation of these accomplishments. The gist was that the future deserved to be informed and not deluded. The gist was that the future would be fulfilled as a measure of its use of the accomplishments of a much longer past.

yahoo! announces book-scanning project to rival google’s

Yahoo, in collaboration with The Internet Archive, Adobe, O’Reilly Media, Hewlett Packard Labs, the University of California, the University of Toronto, The National Archives of England, and others, will be participating in The Open Content Alliance, a book and media archiving project that will greatly enlarge the body of knowledge available online. At first glance, it appears the program will focus primarily on public domain works, and in the case of copyrighted books, will seek to leverage the Creative Commons.

Google Print, on the other hand, is more self-consciously a marketing program for publishers and authors (although large portions of the public domain will be represented as well). Google aims to make money off its indexing of books through keyword advertising and click-throughs to book vendors. Yahoo throwing its weight behind the “open content” movement seems on the surface to be more of a philanthropic move, but clearly expresses a concern over being outmaneuvered in the search wars. But having this stuff available online is clearly a win for the world at large.

The Alliance was conceived in large part by Brewster Kahle of the Internet Archive. He announced the project on Yahoo’s blog:

To kick this off, Internet Archive will host the material and sometimes helps with digitization, Yahoo will index the content and is also funding the digitization of an initial corpus of American literature collection that the University of California system is selecting, Adobe and HP are helping with the processing software, University of Toronto and O’Reilly are adding books, Prelinger Archives and the National Archives of the UK are adding movies, etc. We hope to add more institutions and fine tune the principles of working together.

Initial digitized material will be available by the end of the year.

More in:

NY Times

Chronicle of Higher Ed.

learning from failure: the dot com archive

The University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business is building an archive of primary source documents related to the dot com boom and bust. The Business Plan Archive contains business plans, marketing plans, venture presentations and other business documents from thousands of failed and successful Internet start-ups. In the upcoming second phase of the project, the archive’s creator, assistant professor David A. Kirsch, will collect oral histories from investors, entrepreneurs, and workers, in order to create a complete picture of the so-called internet bubble.

With support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, The Library of Congress, and Maryland’s business school, Mr. Kirsch is creating a teaching tool as well as an historical archive. Students in his management and organization courses at Maryland’s School of Business, must choose a company from the archive and analyze what went wrong (or right). Scholars and students at other institutions are also using it for course assignments and research.

An article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Creating an Archive of Failed Dot-Coms, points out that Mr. Kirsch won’t profit much, despite the success of the archive.

Mr. Kirsch concedes that spending his time building an online archive might not be the best marketing strategy for an assistant professor who would like to earn tenure and a promotion. Online scholarship, he says, does not always generate the same respect in academic circles that publishing hardcover books does.

“My database has 39,000 registered users from 70 countries,” he says. “If that were my book sales, it would be the best-selling academic book of the year.”

Even so, Mr. Kirsch believes, the archive fills an important role in preserving firsthand materials.

“Archivists and scholars normally wait around for the records of the past to cascade down through various hands to the netherworld of historical archives,” he says. “With digital records, we can’t afford to wait.”

fingerprinting text in the age of cut-and-paste

Lexis Nexis has installed new software for detecting plagiarism. As described on their site:

LexisNexis CopyGuard uses pattern-matching technology to identify suspect passages in submitted documents. An easy-to-read report underlines and color codes questionable sentences, with links to the original sources.

This could be an important tool for assuring integrity not only in professional journalism, but also in the emerging class of amateur reporters. But apply it to blogs and CopyGuard might overload and shut down. Bloggers are constantly recycling text, often without clear attribution, or obvious demarcation between quote and original commentary. The bounds of plagiarism seem a bit less clear when you consider that cutting and pasting is one of the main ways we converse online.

(NY Times has story)

the selected, annotated outbox of dave eggers

Email killed the practice of letter-writing so suddenly that we haven’t a chance to think about the consequences. The Times Book Review ran an essay this weekend on the problem this poses for literary historians, biographers and archivists, who long have relied on collected letters and papers to fill in the gaps between a writer’s published work. In the same review, the Times covers a new biography of the legendary critic Edmund Wilson largely based on his correspondences, and last week covered a new collection of the letters of poet James Wright. Letters are often treated as literature in themselves.

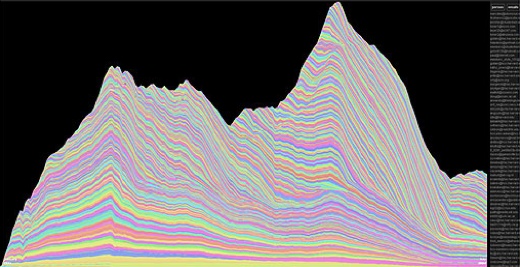

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

There isn’t necessarily anything less rich about email correspondence. It excels at capturing a vibrant volley of words with great immediacy, whereas paper letters permit deeper communiques, fewer and father between. But in some cases, these characterizations do not hold up. With reliable postal service, letters can fly back and forth quite rapidly. And just because an email suddenly appears in your box does not mean that it will be immediately read, let alone replied to. Sometimes we write long email letters, expecting that the receiver is busy and will take time to reply. These differences, true and false, are worth evaluating.

But if collected emails are to become a literary tool, there is no question that we will need more reliable ways of archiving and preserving digital correspondence. We will also need new editorial approaches for collecting and publishing them. A printed volume, or series of volumes, might be insufficient for presenting a massive 4 gigabyte email archive by Dave Eggers (No one wants to read the phone book from cover to cover). And according to the Times piece, Eggers’ agent Andrew Wylie is mulling over such a project. What would make more sense is an electronic edition that is essentially a selected or complete annotated Eggers Outbox, with folders and tags provided for categorization, a powerful search function, and the ability to organize according to your own interests. There would also be browsing and skimming tools that would allow a reader to move rapidly across vast tracts of correspondence and still find what they are looking for. And maybe, a way to email the author yourself and become a part of the living archive.