A November 27 Chicago Tribune article by Julia Keller bundles together hypertext fiction, blogging, texting, and new electronic distribution methods for books under a discussion of “e-literature.” Interviewing Scott Rettberg (of Grand Text Auto) and MIT’s William J. Mitchell, the reporter argues that the hallmark of e-literature is increased consumer control over the shape and content of a book:

Literature, like all genres, is being reimagined and remade by the constantly unfolding extravagance of technological advances. The question of who’s in charge — the producer or the consumer — is increasingly relevant to the literary world. The idea of the book as an inert entity is gradually giving way to the idea of the book as a fluid, formless repository for an ever-changing variety of words and ideas by a constantly modified cast of writers.

A fluid, formless repository? Ever-changing words? This is the Ipod version of the future of literature, and I’m having a hard time articulating why I find it disturbing. It might be the idea that the digitized literature will bring about a sort of consumer revolution. I can’t help but think of this idea as a strange rearticulation of the Marxist rhetoric of the Language Poets, a group of experimental writers who claimed to give the reader a greater role in the production process of a literary work as part of critique of capitalism (more on this here). In the Ipod model of e-literature, readers don’t challenge the capitalist sytem: they are consumers, empowered by their purchasing power.

There’s also a a contradiction in the article itself: Keller’s evolutionary narrative, in which the “inert book” slowly becomes an obsolete concept, is undermined by her last paragraphs. She ends the article by quoting Mitchell, who insists that there will always be a place for “traditional paper-based literature” because a book “feels good, looks good — it really works.” This gets us back to Malcolm Gladwell territory: is it true that paper books will always seem to work better than digital ones? Or is it just too difficult to think beyond what “feels good” right now?

Author Archives: lisa lynch

virtual libraries, real ones, empires

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Last Tuesday, a Washington Post editorial written by Library of Congress librarian James Billington outlined the possible benefits of a World Digital Library, a proposed LOC endeavor discussed last week in a post by Ben Vershbow. Billington seemed to imagine the library as sort of a United Nations of information: claiming that “deep conflict between cultures is fired up rather than cooled down by this revolution in communications,” he argued that a US-sponsored, globally inclusive digital library could serve to promote harmony over conflict:

Libraries are inherently islands of freedom and antidotes to fanaticism. They are temples of pluralism where books that contradict one another stand peacefully side by side just as intellectual antagonists work peacefully next to each other in reading rooms. It is legitimate and in our nation’s interest that the new technology be used internationally, both by the private sector to promote economic enterprise and by the public sector to promote democratic institutions. But it is also necessary that America have a more inclusive foreign cultural policy — and not just to blunt charges that we are insensitive cultural imperialists. We have an opportunity and an obligation to form a private-public partnership to use this new technology to celebrate the cultural variety of the world.

What’s interesting about this quote (among other things) is that Billington seems to be suggesting that a World Digital Library would function in much the same manner as a real-world library, and yet he’s also arguing for the importance of actual physical proximity. He writes, after all, about books literally, not virtually, touching each other, and about researchers meeting up in a shared reading room. There seems to be a tension here, in other words, between Billington’s embrace of the idea of a world digital library, and a real anxiety about what a “library” becomes when it goes online.

I also feel like there’s some tension here — in Billington’s editorial and in the whole World Digital Library project — between “inclusiveness” and “imperialism.” Granted, if the United States provides Brazilians access to their own national literature online, this might be used by some as an argument against the idea that we are “insensitive cultural imperialists.” But there are many varieties of empire: indeed, as many have noted, the sun stopped setting on Google’s empire a while ago.

To be clear, I’m not attacking the idea of the World Digital Library. Having watch the Smithsonian invest in, and waffle on, some of their digital projects, I’m all for a sustained commitment to putting more material online. But there needs to be some careful consideration of the differences between online libraries and virtual ones — as well as a bit more discussion of just what a privately-funded digital library might eventually morph into.

war on text?

Last week, there was a heated discussion on the 1600-member Yahoo Groups videoblogging list about the idea of a videobloggers launching a “war on text” — not necessarily calling for book burning, but at least promoting the use of threaded video conversations as a way of replacing text-based communication online. It began with a post to the list by Steve Watkins and led to responses such as this enthusiastic embrace of the end of using text to communicate ideas:

Audio and video are a more natural medium than text for most humans. The only reason why net content is mainly text is that it’s easier for programs to work with — audio and video are opaque as far as programs are concerned. On top of that, it’s a lot easier to treat text as hypertext, and hypertext has a viral quality.

As a text-based attack on the printed work, the “war on text” debate had a Phaedrus aura about it, especially since the vloggers seemed to be gravitating towards the idea of secondary orality originally proposed by Walter Ong in Orality and Literacy — a form of communication which is involved at least the representation of an oral exchange, but which also draws on a world defined by textual literacy. The vlogger’s debt to the written word was more explicitly acknowledged some posts, such as one by Steve Garfield that declared his work to be a “marriage of text and video.”

Over several days, the discussion veered to cover topics such as film editing, the over-mediation of existence, and the transition from analog to digital. The sophistication and passion of the discussion gave a sense of the way at least some in the video blogging community are thinking, both about the relationship between their work and text-based blogging and about the larger relationship between the written word and other forms of digitally mediated communication.

Perhaps the most radical suggestion in the entire exchange was the prediction that video itself would soon seem to be an outmoded form of communication:

in my opinion, before video will replace text, something will replace video…new technologies have already been developed that are more likely to play a large role in communications over this century… how about the one that can directly interface to the brain (new scientist reports on electroencephalography with quadriplegics able to make a wheelchair move forward, left or right)… considering the full implications of devices like this, it’s not hard to see where the real revolutions will occur in communications.

This comment implies that debates such as the “war on text” are missing the point — other forms of mediation are on the horizon that will radically change our understanding of what “communication” entails, and make the distinction between orality and literacy seem relatively miniscule. It’s an apocalyptic idea (like the idea that the internet will explode), but perhaps one worth talking about.

explosion

![]() A Nov. 18 post on Adam Green’s Darwinian Web makes the claim that the web will “explode” (does he mean implode?) over the next year. According to Green, RSS feeds will render many websites obsolete:

A Nov. 18 post on Adam Green’s Darwinian Web makes the claim that the web will “explode” (does he mean implode?) over the next year. According to Green, RSS feeds will render many websites obsolete:

The explosion I am talking about is the shifting of a website’s content from internal to external. Instead of a website being a “place” where data “is” and other sites “point” to, a website will be a source of data that is in many external databases, including Google. Why “go” to a website when all of its content has already been absorbed and remixed into the collective datastream.

Does anyone agree with Green? Will feeds bring about the restructuring of “the way content is distributed, valued and consumed?” More on this here.

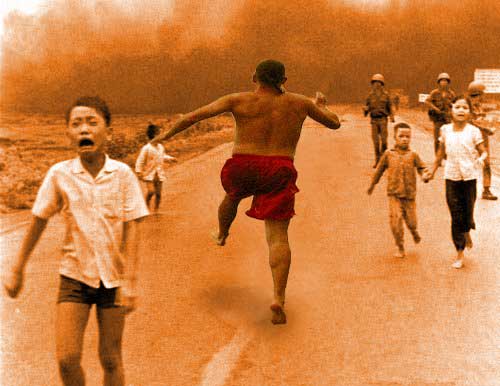

the evils of photoshop?

In a larger essay which bemoans the rise of image culture, Christine Rosen goes after Photoshop and its users in The New Atlantis, a right-leaning journal concerned with the intersection of technology and cultural values. According to Rosen, the software “democratizes the ability to commit fraud,” corrupting its users by giving them easy access to the tools of reality manipulation. She writes:

Photoshop has introduced a new fecklessness into our relationship with the image. We tend to lose respect for things we can manipulate. And when we can so readily manipulate images–even images of presidents or loved ones–we contribute to the decline of respect for what the image represents…

Worrying about photographic fakery isn’t new, of course — as Rosen herself notes, Susan Sontag inveighed against manipulated images in her 1977 work On Photography, and Rosen takes her point that images have been manipulated prior to the age of digitization. Here, however, Rosen’s concern with digital manipulation focuses less on the ability of people to deceive others with altered photos than on the ability of Photoshop to propel its users towards a general irreverence towards the real. This is an interesting inversion of the point that Bob Stein makes in a recent post; namely, that we have less respect for digitally manipulated images than ones which are “real.”

Later in the essay, Rosen suggests that some Photoshop images can be seen as the equivalent of today’s carnival sideshow:

“Photoshop contests” such as those found on the website Fark.com offer people the opportunity to create wacky and fantastic images that are then judged by others in cyberspace. This is an impulse that predates software and whose most enthusiastic American purveyor was, perhaps, P. T. Barnum. In the nineteenth century, Barnum barkered an infamous “mermaid woman” that was actually the moldering head of a monkey stitched onto the body of a fish. Photoshop allows us to employ pixels rather than taxidermy to achieve such fantasies, but the motivation for creating them is the same–they are a form of wish fulfillment and, at times, a vehicle for reinforcing our existing prejudices.

Looking at the Photoshop image above (which I pulled from the first Fark photoshop contest I came across), I can see the root of Rosen’s indignation: there is something offensive about the photo’s casual attitude toward an iconic image. But having seen similarly offensive editorial cartoons that riff on iconic phototographs, I’m not persuaded that Photoshop is the issue. It is true that without Photoshop this image would not have been made; indeed, as Rosen suggests, there is a Photoshop subculture on Fark that promotes the creation of absurd and often offensive images. But can we really make the argument that those who create these images become, in the process, less respectful of the reality they represent? I tend to resist such technological determinism: I would argue, against Rosen, that people manipulate images because they are already irreverent towards them — or, alternately, because they are cynical about the ability of images to represent truth.

“open source media” — not the radio show — launches a best-bloggers site

On Wednesday, November 17, a media corporation called Open Source Media launched a portal site that intends to assemble the best bloggers on the internet in one place. According to the Associated Press, some 70 Web journalists, including Instapundit’s Glenn Reynolds and David Corn, Washington editor of the Nation magazine, have agreed to participate. The site will link to individual blog postings and highlight the best contributions in a special section: bloggers will be paid for content depending on the amount of traffic they generate.

Far from a seat-of-the-pants effort, OSM has $3.5 million dollars in venture capital funding. Supposedly, the site will pay for itself — and pay its bloggers — with the advertising it generates. In the “about” section of the site, the founders of OSM lay out their vision for remaking the future of blogging and media in general:

OSM’s mission is to expand the influence of weblogs by finding and promoting the best of them, providing bloggers with a forum to meet and share resources, and the chance to join a for-profit network that will give them additional leverage to pursue knowledge wherever they may find it. From academics, professionals and decorated experts, to ordinary citizens sitting around the house opining in their pajamas, our community of bloggers are among the most widely read and influential citizen journalists out there, and our roster will be expanding daily. We also plan to provide a bridge between old media and new, bringing bloggers and mainstream journalists–more and more of whom have started to blog–together in a debate-friendly forum.

We at if:book like the idea of a blog portal, especially one staffed by a series of editors selecting the best posts on the blogs they’ve chosen. But this venture — which fits perfectly with John Batelle’s vision for the web’s second coming — also seems to nicely embody the tension between doing good and making money: all that venture capital and overhead is going to put a lot of pressure on OSM to deliver the Oprah of the blogging world, if she’s out there. And paying bloggers based on how many readers they get is certainly going to shape the content that appears on the site. Unlike others who conceived of their blogs from the get-go as small businesses, most of the bloggers chosen by OSM haven’t been trying to make money from their blogs until now.

OSM also shot themselves in the foot by stealing the name of the newish public radio show Open Source Media, which we’ve written about here. The two are currently involved in a dispute over the name. and OSM hasn’t really been able to come up with a good reason why they should keep using a name that belongs to someone else. They have trademarked OSM, and they now refer to their unabbreviated name as “not a trade name,” but “a description of who we are and what we do.”

Needless to say, OSM has generated a fair amount of bad blood by appropriating the name of a nonprofit, and most of the grumbling has taken place in exactly the same place OSM hopes to make a difference — the blogosphere.

a better boom?

An editorial in today’s New York Times by The Search author Jon Battelle makes the argument that the current resurgence in technology stocks is not the sign of another technology “bubble,” but rather an indication that companies have finally figured out how to capitalize on the internet. Batelle writes:

… we are witnessing the Web’s second coming, and it’s even got a name, “Web 2.0” – although exactly what that moniker stands for is the topic of debate in the technology industry. For most it signifies a new way of starting and running companies – with less capital, more focus on the customer and a far more open business model when it comes to working with others. Archetypal Web 2.0 companies include Flickr, a photo sharing site; Bloglines, a blog reading service; and MySpace, a music and social networking site.

In other words, Batelle is pointing out that one way to “get it right” is not to sell content to users, but rather to give them the opportunity to create and search their own content. This is not only good business sense, he says, it’s also more enlightened — the creators of social software such as Flickr are motivated equally by a desire to “do good in the world” and a desire to make money. “The culture of Web 2.0 is, in fact, decidedly missionary,” Batelle writes, “from the communitarian ethos of Craigslist to Google’s informal motto, ‘don’t be evil.'”

O.K. Doing good while making money. Reading this, I’m reminded of Paul Hawken’s Natural Capitalism and the larger sustainability movement — the optimistic philosophy that weaves together environmental ethics and profitability. But is that what’s really going on here? Isn’t the “missionary” culture of the internet a bit OLDER than Web 2.0? Batelle is suggesting that Internet capitalists have gotten all misty and utopian; isn’t it the case that some of the folks who were already misty and utopian have just started making some money?

I guess the more viable comparison here would be to Marc Andreessen’s decision to transform his Mosaic browser from its public-domain University of Illinois incarnation into the Netscape Browser. Andreessen certainly started out as a browser missionary — and, like the companies Batelle sees as characteristic of Internet 2.0, Andreessen’s vision for Netscape (and in the beginning, Jim Clark’s vision as well) was a strong customer focus and open business model. What happened? Netscape’s meteoric success helped inflate the internet “bubble” Batelle’s referring to, and in the end, after the long battle with Microsoft, the company’s misfortunes helped to burst that bubble as well.

So what paradigm fits? Is “Internet 2.0” really new and more socially enlightened? Or are we just seeing a group of social software businesses — and one big search engine — just in the early stages of an inevitable transformation into corporations that are less interested in doing good than making money?

Incidentally, last month, Marc Andressen launched a social networking platform called Ning.

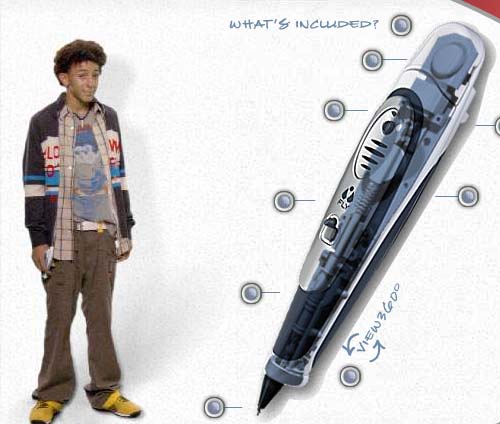

the fly — a hundred dollar “pentop” for the overdeveloped world

Two products that will most likely never be owned by the same teenager: The hundred dollar Laptop from MIT and the hundred dollar “pentop” computerized pen called the Fly. While the hundred dollar laptop (as we’ve said a few times on this site already) is promoted as a device to bring children of underdeveloped countries into the silicon era, the Fly is a device that will help technology-saturated 8 to 14 year olds keep track of soccer practice, learn to read, and solve arithmetic equations. Equipped with a microphone and OCR software, the Fly will read aloud what you write: if you use the special paper that comes with the product, you can draw a calculator and the calculator becomes functional. It’s all very Harold and the Purple Crayon .

Two products that will most likely never be owned by the same teenager: The hundred dollar Laptop from MIT and the hundred dollar “pentop” computerized pen called the Fly. While the hundred dollar laptop (as we’ve said a few times on this site already) is promoted as a device to bring children of underdeveloped countries into the silicon era, the Fly is a device that will help technology-saturated 8 to 14 year olds keep track of soccer practice, learn to read, and solve arithmetic equations. Equipped with a microphone and OCR software, the Fly will read aloud what you write: if you use the special paper that comes with the product, you can draw a calculator and the calculator becomes functional. It’s all very Harold and the Purple Crayon .

In his review of the Fly’s capabilities in todays New York Times, David Pogue is largely enthusiastic about the device, finding it both practical and appealing (if a tad buggy in its original version). Most of all, he seems to think the Fly’s too-cool-for-school additional features are necessary innovation in a market that he says has begun to dry up — digital educational products for children. According to Pogue:

When it comes to children’s technology, a sort of post-educational age has dawned. Last year, Americans bought only one-third as much educational software as they did in 2000. Once highflying children’s software companies have dwindled or disappeared. The magazine once called Children’s Software Review is now named Children’s Technology Review, and over half of its coverage now is dedicated to entertainment titles (for Game Boy, PlayStation and the like) that have no educational component.

If Pogue is right, and educational software is on its way out, does this mean that everything has moved over to the web? And what implication does this downturn have for the hundred dollar laptop project?

malcom gladwell on the social life of paper.

I’m going to devote a series of posts to some (mostly online) texts that have been useful in my teaching and thinking about new media, textuality, and print technologies over the past few years. To start, I’d like to resurrect a three-year old New Yorker piece by Malcom Gladwell called “The Social Life Of Paper,” which distills the arguments of Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper’s book The Myth of the Paperless Office.

Gladwell (like Sellen and Harper) is interested in whether or not giving up paper entirely is practical or even possible. He suggests that for some tasks, paper remains the “killer app;” attempts to digitize such tasks might actually make them more difficult to do. His most compelling example, in the opening paragraph of his article, is the work of the air traffic controller:

On a busy day, a typical air-traffic controller might be in charge of as many as twenty-five airplanes at a time–some ascending, some descending, each at a different altitude and travelling at a different speed. He peers at a large, monochromatic radar console, tracking the movement of tiny tagged blips moving slowly across the screen. He talks to the sector where a plane is headed, and talks to the pilots passing through his sector, and talks to the other controllers about any new traffic on the horizon. And, as a controller juggles all those planes overhead, he scribbles notes on little pieces of paper, moving them around on his desk as he does. Air-traffic control depends on computers and radar. It also depends, heavily, on paper and ink.

Gladwell goes on to make the point that this while kind of reliance on bit of paper drives productivity-managers crazy, anyone who tries to change the way that an air traffic controller works is overlooking a simple fact: the strips of paper supply a stream of “cues” that mesh beautifully with the cognitive labor of the air traffic controller; they are, Gladwell says, “physical manifestations of what goes on inside his head.”

Expanding on this example, Gladwell goes on to argue that while computers are excellent at storing information — much better than the file cabinet with its paper documents — they are often less useful for collaborative work and for the sort of intellectual tasks that are facilitated by piles of paper one can shuffle, rearrange, edit and discard on one’s desk.

“The problem that paper solves,” he writes, “is the problem that most concerns us today, which is how to support knowledge work. In fretting over paper, we have been tripped up by a historical accident of innovation, confused by the assumption that the most important invention is always the most recent. Had the computer come first — and paper second — no one would raise an eyebrow at the flight strips cluttering our air-traffic-control centers.”

This is a pretty strong statement, and I find the logic both seductive and a bit flawed. I’m seduced because I too have piles of paper all over the place, and I’d like to think that these are not simply bits of dead tree, but instead artifacts intrinsic to knowledge work. But I’m skeptical because I think it’s safe to assume that standard cognitive processes can change from generation to generation; for example, those who are growing up using ichat and texting are less likely to think of bits and scraps of paper as representative of cognitive immediacy in the same way I do.

When I’ve taught this essay, I usually also assign Sven Birkets’ Into the Electronic Millenium, a text which argues (in a somewhat Lamarckian way) that electronic mediation is pretty much rewiring our brains in a way that makes it impossible for computer-mediated youth to process information in the same way as their elders. Most of them will agree with both Gladwell and Birkets — yes, there will always be a need for paper because our brain will always process certain things certain ways, but also yes, digital technologies are changing the way that our brain works. My job is to get them to see that those two concepts contradict one another. Birkets espouses a peculiar and curmudgeonly sort of technological determinism. Gladwell, on the other hand, with his focus on an embodied way of knowing, flips the equation and wonders how best to get technology to work FOR us, instead of thinking how technology might work ON us.

I can see why my students are drawn to both arguments: even though I don’t essentially agree with either essay, I often catch myself falling into Birket’s trap of extreme technological determinism — or alternately, thinking, like Gladwell, that because a certain way of doing things seems optimal it must be the “natural” way to do it.

playaways hit the market

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

Over the next few weeks, shoppers at Borders and Barnes and Noble will get a first look at a new form of audiobook, one that seems halfway between an ipod and those greeting cards that play a tune when opened. Playaways are digitized audio books that come embedded in their own playing device; they sell, for the most part, for only slightly more than audio books on cassette or CD. Each Playaway is also wrapped in a replica of the book jacket of the original printed volume: the idea is that users are supposed to walk around with these deck-of-card-sized players dangling around their necks advertising exactly what it is they’re listening to (If you’re the type who always tries to sneak a glance at the book jacket of the person who’s sitting next to you on the bus or subway, the Playaway will make your life much easier). Findaway has about 40 titles ready for release, including Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s American Colossus: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and language training in French, German, Spanish and Italian.

I’m a bit puzzled by the Playaways. I can understand why publishing industry executives would be excited about them, but I’m not so about consumers. The self-contained players are being marketed to an audience that wants an audiobook but doesn’t want to be bothered with CD or MP3 players. The happy customers pictured on the Playaway website are both young and middle aged, but I suspect the real audience for these players would be older Americans who have sworn off computer literacy, and I don’t know that these folks are listening to audio books through headphones.

Speaking of older Americans, if you go down into my parent’s basement, you’ll see a few big shopping bags of books-on-tape that they bought, listened to once, and then found too expensive to throw out yet impossible to give away. This seems clearly to be the future of the Playaways, which can be listened to repeatedly (if you keep changing the batteries) but can’t play anything else than the book they were intended to play. The throwaway nature of the Playaway (suggested, of course, by the very name of the device) is addressed on the company’s website, which provides helpful suggestions on how to get rid of the things once you don’t want ’em anymore. According to the website, you can even ask the Playaway people to send you a stamped envelope addressed to a charitable organization that would be happy to take your Playaway.

This begs the obvious question: what if that organization wants to get rid of the Playway? And so on?

How many times will Playaway shell out a stamp to keep their players out of the landfill?