What would happen if you gave a computer to a group of under-educated kids who had never seen one before? Answer: they would figure out how to use it, all by themselves. Immediately. This is the surprising result of what has come to be known as “the hole in the wall experiment,” conducted by computer scientist, Dr. Sugata Mitra. Dr. Mitra put a computer with internet access in a hole in the wall outside his New Dehli office. According to an article in FRONTLINE/World, “He wanted to see who, if anyone, might use it. To his delight, curious children were immediately attracted to the strange new machine.” All of these children lived in the surrounding slum and had never seen a computer before. However, “Within minutes, children figured out how to point and click. By the end of the day they were browsing. “Given access and opportunity,” observes O’Connor, “the children quickly taught themselves the rudiments of computer literacy.”

The children even developed their own names and associations for the computer icons “They don’t call a cursor a cursor, they call it a sui, which is Hindi for needle. And they don’t call the hourglass symbol the hourglass because they’ve never seen an hourglass before. They call it the damru, which is Shiva’s drum, and it does look a bit like that.”

But the slums of New Dehli are not unique, priviledged kids are also enthusiastic about computers. According to a recent report called “Born to Be Wired”. teens and young adults spend more time using interactive technology than they do watching television. This could mean that are ready for a more interactive and self-guided experience in the classroom. Wise use of media in the curriculum should find ways to exploit this new hunger and allow kids to participate in ways we couldn’t imagine in the past. Jonathan Schwartz, CEO of Sun Microsystems, is calling this “The Participation Age,” a new paradigm for collaborative content creation that seems destined to influence our top-down educational system. The question of how to teach media literacy to kids who seem to grasp these principles intuitively and instantaneously, seems answerable only with a paradigm shift in educational models. Perhaps educators should become more like guides or support persons, providing educational resources and mentor-like advice, empowering kids to engage in self-motivated learning experiences.

Author Archives: kim white

nothing has changed in 3,000 years

![]() Our exploration of digital technology and the revolution it has provoked in our reading and writing practice, tends to focus on the latest gadget and the newest software, but we are also concerned with the things that don’t change and the aspects of human communication that are so deeply a part of our nature that they can not be removed from our reading and writing systems. The first “Information Esthetics” lecture at the Chelsea Museum brought this to the fore last night. Robert Bringhurst spoke about hand-lettered manuscripts, and about typography that respects and preserves the texture and uniqueness of the hand-made mark. He argued for the humanity of fine craftsmanship. He even managed to convince me that slight variations in the shape of letterforms can serve as metaphors for our own individuality.

Our exploration of digital technology and the revolution it has provoked in our reading and writing practice, tends to focus on the latest gadget and the newest software, but we are also concerned with the things that don’t change and the aspects of human communication that are so deeply a part of our nature that they can not be removed from our reading and writing systems. The first “Information Esthetics” lecture at the Chelsea Museum brought this to the fore last night. Robert Bringhurst spoke about hand-lettered manuscripts, and about typography that respects and preserves the texture and uniqueness of the hand-made mark. He argued for the humanity of fine craftsmanship. He even managed to convince me that slight variations in the shape of letterforms can serve as metaphors for our own individuality.

He also made the point that the devices in our writing/reading systems are physiologically based. The average page is a size that can be held easily in our hands and read at arm’s length. Bringhurst showed a slide of an Egyptian manuscript. The size of the papyrus was very similar to page we use today, and the text was composed in blocks around images. Very much like magazine layouts. As I was admiring the beauty of the manuscript, Bringhurst said, “as you can see, nothing has changed in 3,000 years.” That shouldn’t shock me, but it did. I’ve been so absorbed in thinking about the next new thing, I’d forgotten that reading and writing is a very very old thing.

Interesting to think that whether we are reading something written on stone, papyrus, paper, or a computer screen, we need the same things we’ve aways needed: legibility, context, and “texture.” I’m radically summarizing Bringhurst’s lecture (hope I’m doing it justice). The way I understand it, texture is Bringhurst’s way of describing the particular kind of beauty we look for in cultural artifacts. Texture, is evidence of complexity, information, meaning and the imperfect human hand at work.

So, I’m thinking about how this “texture” manifests in digital manuscripts and it seems to me that it does so in several ways including: the craftsmanship of the digital document itself (which includes the code, the interface, and the composition), the richness of information/meaning that resides in virtual layers or as “links” within the text, and the way beauty can be crafted out of the physical material itself–light emitted by a computer screen.

(photo by Alex Itin)

the book as community: wikicities

Jimmy Wales, creator of the not-for-profit Wikipedia has launched a for-profit, ad-supported site called Wikicities, which offers users “free MediaWiki hosting for a community to build a free content wiki-based website.”

In yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, Vauhini Vara noted that gaming communities have been particularly enthusiastic. “Laurence Parry, a 22-year-old computer programmer, who co-founded a wiki dedicated to a computer-game series called Creatures and now spends up to several hours a day updating the site. Before the Creatures wiki existed, fans of the game swapped tips in scattered online forums.”

The brilliance of this idea is it just might succeed in centralizing the online gathering place. Internet-based tribal communities that meet to discuss common interests can create their own “city” within the greater universe of Wikicities.com The communal spaces can be defined in the recommended “mission statement.” Wikicities also gives users advice on “developing your community” and “setting boundaries.”

In a recent Wired Magazine article Daniel H. Pink wondered if this is, in fact, a new idea.

It may feel like we’ve been down this road before – remember GeoCities and theglobe.com? But Wales says this is different because those earlier sites lacked any mechanism for true community. “It was just free home-pages,” he says. WikiCities, he believes, will let people who share a passion also share a project. They’ll be able to design and build projects together.

the visible human: illuminated manuscripts and medical illustration

I’ve always been fascinated by medical illustration. My undergraduate degree was in studio art–figurative sculpture and painting–so I marveled at the technical skill required to make the drawings themselves. But I also appreciated the text. In order to sculpt the human figure, I needed to know precisely what was happening under the skin. I memorized all the muscles and how they moved, every bone in the skeletal system and where it stuck out. I absorbed books like “Gray’s Anatomy,” and Frank Netter’s “Atlas of Human Anatomy.” I thought of them as illuminated manuscripts. The text alone would have been less than useful to me and the illustration without the text would not been enough either. I thought it would be interesting to look at some of these illuminations, think about the intermingling of text and image, and examine their “born digital” equivalents.

Below are two Persian illuminations that I find particularly compelling. The first details the human muscle system. I like its primative feel, the squatting pose and the way the notations look like tribal tattoo, ritual scarification patterns, or the sinews of the muscle itself. The second drawing has the opposite effect, an exaggerated gentility, the patient sits, fully conscious, politely allowing the surgeon to slice open his cranium. Captions for the drawings were taken from an article entitled, “Arab Roots of European Medicine” by David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD.

The Anatomy of the Human Body. Persian notations detail the human muscle system in Mansur ibn Ilyas’s late-14th century Tashrih-I Badan-I Insan.

An illustration in The Surgeon’s Tract, an Ottoman text written by Sharaf al-Din in about 1465, indicates where on the scalp incisions should be made.

![]()

Above left: A Dead or Moribund Man in Bust Length; a Detail of the Jaw and Neck; the Muscular and Vascular Systems of the Shoulder and Arm (recto). Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452-Cloux, 1519).

Above right: Detail Section of the Mouth and Throat; the Muscular System of the Shoulder and Arm (verso). Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452-Cloux, 1519).

Renaissance European artist Leonardo da Vinci, created sublime illuminations, heavily annotated with notations made during dissections. The effect of the notations reminds us that these drawings were “studies” of the human body and its mysteries. For me, these drawings are as compelling as Da Vinci’s more “finished” works. When I was seven months pregnant, I waited in line for four hourse to see the Met exhibition: Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman which included the drawings above. It was worth it.

I should also mention one of his contemporaries, Andreas Vesalius, (1514-1564) who was the author of an extremely influential atlas of anatomy.

The modern-day equivalent of Vesalius, might be Frank H. Netter, M.D., whose brillantly illustrated “Atlas of Human Anatomy,” is required reading for many first-year medical students.

Flix Productions’3D animation of the beating heart (click on image) could be considered a born digital update on Netter’s style of medical illustration. No text on this one (so it doesn’t really belong here) but I wanted to indicate how 2D drawings are being “improved” by digital technolgy. This animation gives a 360 view of the heart and shows it in motion. I imagine the text might be read by a narrator or included on the screen on in a pop-out window.

![]()

We can’t overlook, “Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body,” I found this (above left) image in the Bartleby.com edition which is available online. The drawing also seems to be a rather eerie premonition of the sonogram (above right). I like to think of sonograms as machine-generated born digital illuminations. I’ve cropped the text off the one above to protect privacy, but it would normally have useful information about the mother and fetus printed in the margins.

Another iteration of the born digital illumination, this 3D animation of a normal birth created by Nucleus Medical Art. It looks so painless in the movies.

graphic novel as illuminated manuscript

The institute is hosting a competition called Born Digital 1: Illumination, which asks artists, writers, programmers, and designers to address the conceptual underpinnings of illuminated manuscripts in the context of the born digital artifact. We are playing somewhat loose with the term “illuminated manuscript.” Our “Born Digital” contest asks for a single page rather than an entire book and is not necessarily interested in a literal reinvention of the form (unless you’ve come up with a particularly great one). We are intrigued by the fact that illuminated manuscripts do not separate text and image into different disciplines requiring separate platforms for display and critical discourse. We find that, in the workshop of the digital medium, disciplinary amalgams are once again emerging, and we would like to examine this shift.

Without attempting to give a history of the evolution of this form, I will, over the next several days, point out a few contemporary models that pay tribute to medieval illumination. The graphic novel comes immediately to mind. Chris Ware’s, “Jimmy Corrigan the Smartest Kid on Earth, Art Spiegelman’s, “Maus,” and David B’s, “This Sweet Sickness,” have shown us the power of image and text working in tandem to deliver a profound aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.

Early digital versions of the graphic novel include Pyramids of Mars, which was published in 1997 by Richard Douglas and Geoffrey Holmes, and claims to be the first downloadable digital graphic novel. And Scott Frazier’s TRANSCENDENCE which the author describes as: partially animated, partially illustrated and partially text. It will, hopefully, stretch the bounds of multimedia and become something new, more than a mere fusion of comic and animation.

![]() And thanks to friend Douglas Wolk, the absolute authority on graphic novels (and one of the smartest and nicest guys I know) for the following recommendations: “Patrick Farley’s, “The Spiders,” is wonderful and uses the medium nicely. Dylan Meconis’s, “Bite Me” is pretty much just scanned images, but she serialized the whole thing online, and she’s like 19 years old and super-fun.”

And thanks to friend Douglas Wolk, the absolute authority on graphic novels (and one of the smartest and nicest guys I know) for the following recommendations: “Patrick Farley’s, “The Spiders,” is wonderful and uses the medium nicely. Dylan Meconis’s, “Bite Me” is pretty much just scanned images, but she serialized the whole thing online, and she’s like 19 years old and super-fun.”

I hope this serves as a useful beginning for discussion on graphic novel as illuminated manuscript. I’m relying on readers to help me flesh the idea out.

describing humanity in data sets

Yahoo’s recently released commemorative microsite, “Yahoo Netrospective: 10 years, 100 moments,” is a selection of one hundred significant moments in the history of the web (1995-2005). The format for the site was inspired by the work of information architect Jonathan Harris. Harris created 10 x 10, a piece visually identical to, but considerably more interesting than the Yahoo birthday card, (whose content leans quite heavily toward self-promotion, i.e. there are 20 mentions of Yahoo products and no mention at all of Google.) By contrast, Harris’ 10 x 10 builds its fascinating content from RSS feeds. The piece selects the most frequently used words from the major news networks to assemble an hourly “portrait” of our world. “What interests me is trying to find descriptions of humanity in very large data sets, creating programs that tell us something about ourselves,” Harris told Wired News. “We set them free and they come back and tell us what we are like.”

What makes Harris’ work interesting is the self-discipline he exercises in designing these objective systems. By withholding the urge to edit (except, perhaps, when Yahoo is involved) he allows an authentic “picture” of current events, of human behavior online, of the fluid exchange of words and images. His linguistic self-portrait WordCount, harvests data from the British National Corpus. WordCount displays the 86,800 most commonly used words in the English language in order of their commonness. Harris alleges that “observing closely ranked words tells us a great deal about our culture. For instance, “God” is one word from “began”, two words from “start”, and six words from “war”. I tried WordCount and was instantly addicted. To read WordCount or 10 x 10, you have to interact with it and bring meaning to it. Or put another way, you have to be willing to bring meaning to it. This is quite different from the way we experience traditional narratives, whose structure and meaning are crafted by the writer and handed down to the reader. I am eagerly anticipating his next project which, he told Wired, “involves looking at human feelings on a large scale from the web.”

How Do Books Work? A Conversation with Mom

My mother, a veteran kindergarten teacher, who, over the last 30 years, has taught scores of children to read, recently engaged me in an interesting conversation regarding the ebook vs. the paper book. She was responding to something I posted a few months ago called: Children and Books: Forming a World-view. She was particularly interested in this passage:

My son is 14 months old and he loves books. That is because his grandmother sat down with him when he was six months old and patiently read to him. She is a kindergarten teacher, so she is skilled at reading to children. She can do funny voices and such. My son doesn’t know how to read, he barely has a notion of what story is, but his grandmother taught him that when you open a book and turn its pages, something magical happens–characters, voices, colors–I think this has given him a vague sense of how meaning is constructed. My son understands books as objects printed with symbols that can be translated and brought to life by a skilled reader. He likes to sit and turn the pages of his books and study the images. He has a relationship with books, but he wouldn’t have that if someone hadn’t taught him. My point is, even after you learn to read, the book is still part of a complex system of relationships. It is almost a matter of chance, in some ways, which books are introduced to you and opened to you by someone.

My son is 14 months old and he loves books. That is because his grandmother sat down with him when he was six months old and patiently read to him. She is a kindergarten teacher, so she is skilled at reading to children. She can do funny voices and such. My son doesn’t know how to read, he barely has a notion of what story is, but his grandmother taught him that when you open a book and turn its pages, something magical happens–characters, voices, colors–I think this has given him a vague sense of how meaning is constructed. My son understands books as objects printed with symbols that can be translated and brought to life by a skilled reader. He likes to sit and turn the pages of his books and study the images. He has a relationship with books, but he wouldn’t have that if someone hadn’t taught him. My point is, even after you learn to read, the book is still part of a complex system of relationships. It is almost a matter of chance, in some ways, which books are introduced to you and opened to you by someone.

Hi Kim,

I was really touched by the comments about Aidan and me. I truly believe that a child’s first experiences with books (even before he/she can read) are vital to his/her enjoyment of them in later life. I would like to add to your observations about books being intertwined with experiences and how I see very young children learning to love literature.

Much research has been done on how and why children want to learn to read. We know that the single most important thing that parents can do to make an avid reader of their child, is to read to them. We also know that, for most children, it takes approximately 700 to 1000 hours of lap/read time to have them ready to read. That sounds like a great deal of time, but if you put your child in your lap from the time they are 6 months old until they are 5, that is about 3 minutes a day. If you are holding your child close to you and together you read a colorful, well-written and illustrated children’s book, 3 minutes will disappear very quickly. I cannot imagine any 6 month old interested in a book written in a machine. YES, they would be interested in the machine, but the book (the story and the beautiful illustrations) would be lost to the small child. Because–the biggest part of the reading experience for a small child is being able to participate by holding the book themselves, turning the pages, pointing at the pictures, going back to the pages that they most enjoyed, in other words interacting with a handheld book. A machine will not offer this opportunity.

When children come to my preschool/kindergarten classroom the ones who have had many experiences with books have a wealth of background and knowledge that others do not have. Even if they do not read, when they are given the initial literacy exam they have learned by experience how to hold a book, which is the front versus the back, where do you start reading, what’s wrong with this picture? Etc., etc., etc.

Perhaps, I am jumping too far ahead in assuming that all, even children’s books will ultimately be on machines. If this is to be the case, it will DRASTICALLY change the way children are taught to read and how early experiences prepare them for this task.

Thanks mom, this is great. It brought up a few questions, I wonder if you can address them. I agree that the nurturing aspect of reading to a child is most important, but if the child is sitting in my lap while we look at a book on the computer screen, how will the experience be different? Also, I’m trying to understand why paper books are better than screen-based books, if the book progresses by clicking a mouse or touching the screen, why would those actions be less developmentally useful than page turning? Also, why wouldn’t a 6 month old be interested in a screen-based book? Aidan was mesmerized by the baby einstein videos, those are screen-based. When I play dvds on my laptop machine he screams because he wants to touch the keys and I have to restrain him. He loves pushing buttons, clicking my mouse and touching the screen. It seems like these are skills that he will have to learn in this computer-driven world, why not link computers with reading/nurturing/sitting in mom’s lap, etc., from an early age?

Hi Kim,

These are excellent questions and I do not know how to answer them, as no research has been done in that area. (Great place for Ph.D. research, or for another year of grant money.) You are right, a small child is mesmerized by things they see on the TV and on the computer screen. If you, the parent, is holding the child, perhaps the child would get the same nurturing experiences with the book machine as with a hand held book. I have only had experiences and read research about the hand held book, this is a whole new arena. I do agree that young children of this generation will have to have extensive technological knowledge and why not start it early. My kindergartners went to the computer lab once a week for 45 minutes and most of them were totally computer savvy and those that were not caught on quickly, as they are not afraid to experiment. As to the point that pushing a button is as developmentally appropriate as the skill of turning a page, they are very different skills, but if books are to be in ibooks, turning a page will not be a skill that young children need. Basically this is all uncharted territory and these questions are exactly what “the future of the book” should be asking. Bravo!

harnessing the collective mind: the ultimate networked book

Dr. Douglas C. Engelbart, who invented the computer mouse and is also credited with pioneering online computing and e-mail, advocates networked books as tools for building what he calls a “dynamic knowledge repository. This would be a place,” Engelbart said, in a recent interview with K. Oanh Ha at Mercury News, “where you can put all different thoughts together that represents the best human understanding of a situation. It would be a well-formed argument. You can see the structure of the argument, people’s assertions on both sides and their proof. This would all be knit together. You could use it for any number of problems. Wikipedia is something similar to it.”

How to conceptualize, organize, build, and use a “book” of that scale, is the project of Engelbart’s Bootstrap Institute. In the “Reasons for Action” section of their website, Engelbart gives his perception of why we need such a book. It reads as follows:

• Our world is a complex place with urgent problems of a global scale.

• The rate, scale, and complex nature of change is unprecedented and beyond the capability of any one person, organization, or even nation to comprehend and respond to.

• Challenges of an exponential scale require an evolutionary coping strategy of a commensurate scale at a cooperative cross-disciplinary, international, cross-cultural level.

• We need a new, co-evolutionary environment capable of handling simultaneous complex social, technical, and economic changes at an appropriate rate and scale.

• The grand challenge is to boost the collective IQ* of organizations and of society. A successful effort brings about an improved capacity for addressing any other grand challenge.

• The improvements gained and applied in their own pursuit will accelerate the improvement of collective IQ. This is a bootstrapping strategy.

• Those organizations, communities, institutions, and nations that successfully bootstrap their collective IQ will achieve the highest levels of performance and success.

“Towards High-Performance Organizations: A Strategic Role for Groupware,” a paper written by Dr. Engelbart in 1992, outlines practical ideas for the architecture of this vast and comprehensive networked book.

All of this is meaty food for thought with regards to our ongoing thread “the networked book.” I am wondering what blog readers think about this? Assuming it becomes possible to collect, map, and analyze the thoughts and opinions of a large community, will it really be to our advantage? Will it necessarily lead to solving the complex problems that Dr. Engelbart speaks of, or will the grand group-think lead to certain dystopian outcomes which may, perhaps, cancel out its IQ-raising value?

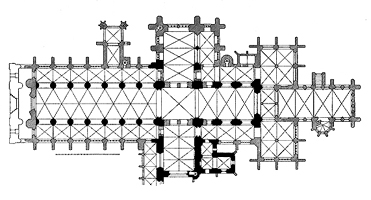

building the cathedral: collaborative authorship and the internet

The World Wide Web is, quite possibly, the most collaborative multi-cultural project in the history of mankind. Millions of people have contributed personal homepages, blogs, and other sites to the growing body of human expression available online. It is, one could say, the secular equivalent of the medieval cathedral, designed by a professional, but constructed by non-professionals, regular folk who are eager to participate in the construction of a legacy. Such is the context for projects like Wikimedia and the Semantic Web, designed by elite programmers, built by the masses.

One of the most pressing questions with regard to collaborative authorship is, can the content be trusted? Does the anonymous group author have the same authority as the credentialed single author? Is our belief in the quality of information inextricably connected to our belief in the authority of the writer? Wikimedia (the non-profit organization that initiated Wikipedia, Wikibooks,, Wiktionary, Wikinews, Wikisource, and Wikiquote) addresses these concerns by offering a new model for collaborative authorship and peer review. Wikipedia’s anonymously published articles undergo peer review via direct peer revision. All revisions are saved and linked; user actions are logged and reversible. “This type of constant editing,” Wikimedia co-director Angela Beesley alleges, “allows you to trust the content over time.” The ambition of Wikimedia is to create a neutral territory where, through open debate, consensus can be reached on even the most contentious topics. The Wikimedia authoring system sets up a democratic forum where contributors construct their own rulespace and policies emerge from consensus-based, rather than top-down, processes. So the authority of the Wikimedia collaborative book depends, in part, on a collective self-discipline that is defined by and enforced by the group.

One of the most pressing questions with regard to collaborative authorship is, can the content be trusted? Does the anonymous group author have the same authority as the credentialed single author? Is our belief in the quality of information inextricably connected to our belief in the authority of the writer? Wikimedia (the non-profit organization that initiated Wikipedia, Wikibooks,, Wiktionary, Wikinews, Wikisource, and Wikiquote) addresses these concerns by offering a new model for collaborative authorship and peer review. Wikipedia’s anonymously published articles undergo peer review via direct peer revision. All revisions are saved and linked; user actions are logged and reversible. “This type of constant editing,” Wikimedia co-director Angela Beesley alleges, “allows you to trust the content over time.” The ambition of Wikimedia is to create a neutral territory where, through open debate, consensus can be reached on even the most contentious topics. The Wikimedia authoring system sets up a democratic forum where contributors construct their own rulespace and policies emerge from consensus-based, rather than top-down, processes. So the authority of the Wikimedia collaborative book depends, in part, on a collective self-discipline that is defined by and enforced by the group.

The collaborative authoring environment engendered by the web will make even more ambitious and far-reaching projects possible. Projects like the Semantic Web, which aims to make all content searchable by allowing users to assign semantic meaning to their work, will organize the prodigious output of collaborative networks, and could, potentially, cast the entire web as a collaboratively authored “book.”

collecting and archiving the future book

The collection and preservation of digital artworks has been a significant issue for museum curators for many years now. The digital book will likely present librarians with similar challenges, so it seems useful to look briefly at what curators have been grappling with.

At the Decade of Web Design Conference hosted by the Institute for Networked Cultures. Franziska Nori spoke about her experience as researcher and curator of digital culture for digitalcraft at the Museum for Applied Art in Frankfurt am Main. The project set out to document digital craft as a cultural trend. Digital crafts were defined as “digital objects from everyday life,” mostly websites. Collecting and preserving these ephemeral, ever-changing objects was difficult, at best. A choice had to be made between manual selection, or automatic harvesting. Nori and her associates chose manual selection. The advantage of manual selection was that critical faculties could be employed. The disadvantage was that subjective evaluations regarding an object’s relevance were not always accurate, and important work might be left out. If we begin to treat blogs, websites, and other electronic ephemera as cultural output worthy of preservation and study (i.e. as books), we will have to find solutions to similar problems.

The pace at which technology renews and outdates presents a further obstacle. There are, currently, two ways to approach durability of access to content. The first, is to collect and preserve hardware and software platforms, but this is extremely expensive and difficult to manage. The second solution, is to emulate the project in updated software. In some cases, the artist must write specs for the project, so it can be recreated at a later date. Both these solutions are clearly impractical for digital librarians who must manage hundreds of thousand of objects. One possible solution for libraries, is to encourage proliferation of objects. Open source technology might make it possible for institutions to share data/objects, thus creating “back-up” systems for fragile digital archives.

Nori ended her presentation with two observations. “Most societies create their identity through an awareness of their history.” This, she argues, compells us to find ways to preserve digital communications for posterity. She notes that cultural historians, artists, and researchers “are worried about a future where these artifacts will not be accessible.”