As privacy fears around search engines and the Justice Department continue to rise, the issue of personal privacy is being thrust, once again, into the public spotlight. The conversation generally goes like this: “All the search engines are collecting information about us. There isn’t enough protection for our personal information. Companies must do more.” Suggestions of what ‘more’ is are numerous, while solutions are few and far between. Social engineering solutions that do exist fail to include effective ways of securing online activities. Technical services that allow you to completely protect your identity are geek oriented and lacking the polish of Google or Yahoo!.

As privacy fears around search engines and the Justice Department continue to rise, the issue of personal privacy is being thrust, once again, into the public spotlight. The conversation generally goes like this: “All the search engines are collecting information about us. There isn’t enough protection for our personal information. Companies must do more.” Suggestions of what ‘more’ is are numerous, while solutions are few and far between. Social engineering solutions that do exist fail to include effective ways of securing online activities. Technical services that allow you to completely protect your identity are geek oriented and lacking the polish of Google or Yahoo!.

Why is this privacy thing an issue, anyway? People feel strongly about their privacy and protecting their identities, but are lazy when it comes time to protect themselves. Should this be taken for a disinterested acknowledgement that we don’t care about our personal data? Short answer: no. If we look at what’s happening on the other side of things—the data that people put out there willingly, on sites like MySpace, and blogs, and flickr, I think the answer is obvious. Personal data is constantly being added to the virtual space because it represents who we are.

Identity production is a large part of online culture, and has been from the very first days of the Well. Our personal information is important to us, but the apathy arises from the fact that we have no substantitive rights when it comes to controlling it [1].

There are a few outlets where we can wrangle our information into a presentation of ourselves, but usually our data accumulates in drifts, in the dusty corners of databases. When search engines crawl through those databases the information unintentionally coalesces into representations of us. In the real world the ability to keep distance between social spheres is fundamental to the ability to controlling your identity; there is no distance in cyberspace. Your info is no longer dispersed among the different spheres of shopping sites, email, blogs, comments, or bulletin boards, reviews. Search engines collapse that distance completely and your distributed identity becomes an aggregate one; one we might not recognize if it came up to us on the street.

There are two ways to react: 1) with alarm: attempt to keep things wrapped in layers of protection, possibly remove it entirely, and call for greater control and protection of our personal information. Or 2) with grace: acknowledge our multiple identities, and create a meta-identity, while still making a call for better control of our personal data. The first reaction is about identity control and privacy and relies on technical solutions or non-participation. Products like sxip and schemes like openID allow you to confirm that you are who you say you, and groups like EPIC, and federal legislation (HIPAA, FERPA, definitely not the PATRIOT Act) help protect your information. But eventually this route is not productive—it doesn’t embrace the reality of living with and within a networked environment. The second reaction is about “identity production” [2], and that’s where sites like MySpace and blogs reign. There’s also a new service, ClaimID, that will help you create a meta-identity with a slick, web 2.0 workflow (full disclosure: the founder is a former colleague).

![]() ClaimID is interesting in several respects. It let’s you actively manage your identity by aggregating information about yourself through searches, then tagging each item with several levels of aboutness. So you could say that your website is about you, and by you, whereas an article that mentions your name in conjunction with a project is not about you, or by you. Still, it’s part of your online persona. An interview: about you, not by you. A short history of New York: by you, not about you. ClaimID allows you to have these different permutations of relationship that help define the substance within and the ownership of each item. Everything can be tagged with keywords to link items. What you end up with is a web of yourself, annotated and organized so that people can get to know you in the way you want to be known.

ClaimID is interesting in several respects. It let’s you actively manage your identity by aggregating information about yourself through searches, then tagging each item with several levels of aboutness. So you could say that your website is about you, and by you, whereas an article that mentions your name in conjunction with a project is not about you, or by you. Still, it’s part of your online persona. An interview: about you, not by you. A short history of New York: by you, not about you. ClaimID allows you to have these different permutations of relationship that help define the substance within and the ownership of each item. Everything can be tagged with keywords to link items. What you end up with is a web of yourself, annotated and organized so that people can get to know you in the way you want to be known.

This helps combat the unintentional aggregation of information that happens within search engines. But we also need to be aware that intentional aggregation does not mean it is trustworthy information, just as unintentional does not always mean “true to life”. We have a sense that when people manage their identities that they are repositioning the real in favor of a something more appropriate for the audience. We therefore put greater stock in what we find that seems unintentional—yet this information is not logically more reliable. We have to be critical of both the presented, vetted information and the aggregated, unintentional information. We still need privacy rights, and tools to help protect our identities from theft, spoofing, or intrusion, but in the meantime we have the opportunity to actively negotiate the bits and pieces of our identities on the network.

Author Archives: jesse wilbur

RDF = bigger piles

Last week at a meeting of all the Mellon funded projects I heard a lot of discussion about RDF as a key technology for interoperability. RDF (Resource Description Framework) is a data model for machine readable metadata and a necessary, but not sufficient requirement for the semantic web. On top of this data model you need applications that can read RDF. On top of the applications you need the ability to understand the meaning in the RDF structured data. This is the really hard part: matching the meaning of two pieces of data from two different contexts still requires human judgement. There are people working on the complex algorithmic gymnastics to make this easier, but so far, it’s still in the realm of the experimental.

So why pursue RDF? The goal is to make human knowledge, implicit and explicit, machine readable. Not only machine readable, but automatically shareable and reusable by applications that understand RDF. Researchers pursuing the semantic web hope that by precipitating an integrated and interoperable data environment, application developers will be able to innovate in their business logic and provide better services across a range of data sets.

Why is this so hard? Well, partly because the world is so complex, and although RDF is theoretically able to model an entire world’s worth of data relationships, doing it seamlessly is just plain hard. You can spend time developing a RDF representation of all the data in your world, then someone else will come along with their own world, with their own set of data relationships. Being naturally friendly, you take in their data and realize that they have a completely different view of the category “Author,” “Creator,” “Keywords,” etc. Now you have a big, beautiful dataset, with a thousand similar, but not equivalent pieces. The hard part—determining relationships between the data.

We immediately considered how RDF and Sophie would work. RDF importing/exporting in Sophie could provide value by preparing Sophie for integration with other RDF capable applications. But, as always, the real work is figuring out what it is that people could do with this data. Helping users derive meaning from a dataset begs the question: what kind of meaning are we trying to help them discover? A universe of linguistic analysis? Literary theory? Historical accuracy? I think a dataset that enabled all of these would be 90% metadata, and 10% data. This raises another huge issue: entering semantic metadata requires skill and time, and is therefore relatively rare.

In the end, RDF creates bigger, better piles of data—intact with provenance and other unique characteristics derived from the originating context. This metadata is important information that we’d rather hold on to than irrevocably discard, but it leaves us stuck with a labyrinth of data, until we create the tools to guide us out. RDF is ten years old, yet it hasn’t achieved the acceptance of other solutions, like XML Schemas or DTD’s. They have succeeded because they solve limited problems in restricted ways and require relatively simple effort to implement. RDF’s promise is that it will solve much larger problems with solutions that have more richness and complexity; but ultimately the act of determining meaning or negotiating interoperability between two systems is still a human function. The undeniable fact of it remains— it’s easy to put everyone’s data into RDF, but that just leaves the hard part for last.

yahoo! ui design library

There are several reasons that Yahoo! released some of their core UI code for free. A callous read of this would suggest that they did it to steal back some goodwill from Google (still riding the successful Goolge API release from 2002). A more charitable soul could suggest that Yahoo! is interested in making the web a better place, not just in their market-share. Two things suggest this—the code is available under an open BSD license, and their release of design patterns. The code is for playing with; the design patterns for learning from.

There are several reasons that Yahoo! released some of their core UI code for free. A callous read of this would suggest that they did it to steal back some goodwill from Google (still riding the successful Goolge API release from 2002). A more charitable soul could suggest that Yahoo! is interested in making the web a better place, not just in their market-share. Two things suggest this—the code is available under an open BSD license, and their release of design patterns. The code is for playing with; the design patterns for learning from.

The code is squarely aimed at folks like me who would struggle mightily to put together a default library to handle complex interactions in Javascript using AJAX (all the rage now) while dealing with the intricacies of modern and legacy browsers. Sure, I could pull together the code from different sources, test it, tweak it, break it, tweak it some more, etc. Unsurprisingly, I’ve never gotten around to it. The Yahoo! code release will literally save me at least a hundred hours. Now I can get right down to designing the interaction, rather than dealing with technology.

The design patterns library is a collection of best practice instructions for dealing with common web UI problems, providing both a solution and a rationale, with a detailed explanation of the interaction/interface feedback. This is something that is more familiar to me, but still stands as a valuable resource. It is a well-documented alternate viewpoint and reminder from a site that serves more users in one day than I’m likely to serve in a year.

Of course Yahoo! is hoping to reclaim some mind-space from Google with developer community goodwill. But since the code is general release, and not brandable in any particular way (it’s all under-the-hood kind of stuff), it’s a little difficult to see the release as a directly marketable item. It really just seems like a gift to the network, and hopefully one that will bear lovely fruit. It’s always heartening to see large corporations opening their products to the public as a way to grease the wheels of innovation.

reading fewer books

We’ve been working on our mission statement (another draft to be posted soon), and it’s given me a chance to reconsider what being part of the Institute for the Future of the Book means. Then, last week, I saw this: a Jupiter Research report claims that people are spending more time in front of the screen than with a book in their hand.

“the average online consumer spends 14 hours a week online, which is the same amount of time they watch TV.”

That is some 28 hours in front of a screen. Other analysts would say it’s higher, because this seems to only include non-work time. Of course, since we have limited time, all this screen time must be taking away from something else.

The idea that the Internet would displace other discretionary leisure activities isn’t new. Another report (pdf) from the Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society suggests that Internet usage replaces all sorts of things, including sleep time, social activities, and television watching. Most controversial was this report’s claim that internet use reduces sociability, solely on the basis that it reduces face-to-face time. Other reports suggest that sociability isn’t affected. (disclaimer – we’re affiliated with the Annenberg Center, the source of the latter report).

Regardless of time spent alone vs. the time spent face-to-face with people, the Stanford study is not taking into account the reason people are online. To quote David Weinberger:

“The real world presents all sorts of barriers that prevent us from connecting as fully as we’d like to. The Web releases us from that. If connection is our nature, and if we’re at our best when we’re fully engaged with others, then the Web is both an enabler and a reflection of our best nature.”

—Fast Company

Hold onto that thought and let’s bring this back around to the Jupiter report. People use to think that it was just TV that was under attack. Magazines and newspapers, maybe, suffered too; their formats are similar to the type of content that flourishes online in blog and written-for-the-web article format. But books, it was thought, were safe because they are fundamentally different, a special object worthy of veneration.

“In addition to matching the time spent watching TV, the Internet is displacing the use of other media such as radio, magazines and books. Books are suffering the most; 37% of all online users report that they spend less time reading books because of their online activities.”

The Internet is acting as a new distribution channel for traditional media. We’ve got podcasts, streaming radio, blogs, online versions of everything. Why, then, is it a surprise that we’re spending more time online, reading more online, and enjoying fewer books? Here’s the dilemma: we’re not reading books on screens either. They just haven’t made the jump to digital.

While there has been a general decrease in book reading over the years, such a decline may come as a shocking statistic. (Yes, all statistics should be taken with a grain of salt). But I think that in some ways this is the knock of opportunity rather than the death knell for book reading.

…intensive online users are the most likely demographic to use advanced Internet technology, such as streaming radio and RSS.

So it is ‘technology’ that is keeping people from reading books online, but rather the lack of it. There is something about the current digital reading environment that isn’t suitable for continuous, lengthy monographs. But as we consider books that are born digital and take advantage of the networked environment, we will start to see a book that is shaped by its presentation format and its connections. It will be a book that is tailored for the online environment, in a way that promotes the interlinking of the digital realm, and incorporates feedback and conversation.

At that point we’ll have to deal with the transition. I found an illustrative quote, referring to reading comic books:

“You have to be able to read and look at the same time, a trick not easily mastered, especially if you’re someone who is used to reading fast. Graphic novels, or the good ones anyway, are virtually unskimmable. And until you get the hang of their particular rhythm and way of storytelling, they may require more, not less, concentration than traditional books.”

—Charles McGrath, NY Times Magazine

We’ve entered a time when the Internet’s importance is shaping the rhythms of our work and entertainment. It’s time that books were created with an awareness of the ebb and flow of this new ecology—and that’s what we’re doing at the Institute.

GAM3R 7H30RY: part 2

Read Part 1

We had a highly productive face to face meeting with Ken this afternoon to review the prior designs and to try and develop, collaboratively, a solution based on the questions that arose from those designs. We were aiming for a solution that provides a compelling interface for Ken’s book and also encourages open-ended discussion of the themes and specific games treated in the book.

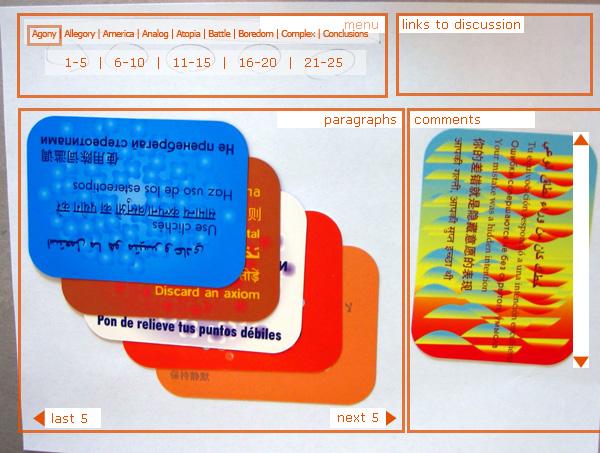

What we came up with was a prototype of a blog/book page that presents the entire text of GAM3R 7H30RY, and a discussion board based around the games covered in the book, each corresponding with a specific chapter. These are:

- Allegory (on The Sims)

- America (on Civilization III)

- Analog (on Katamari Damarcy)

- Atopia (on Vice City)

- Battle (on Rez)

- Boredom (on State of Emergency)

- Complex (on Deus Ex)

- Conclusions (on SimEarth)

Unlike the thousand of gaming forums that already exist throughout the web, this discussion space will invite personal and social points of view, rather than just walkthroughs and leveling up cheats.

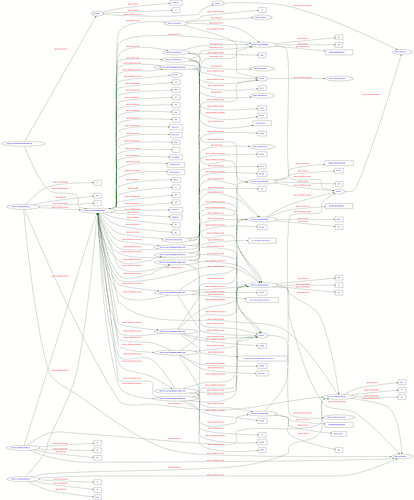

We also discussed the fact that discussion boards tend towards opacity as they grow, and ways to alleviate that situation. Growth is good; it reflects a rich back and forth between board participants. Opacity is bad; it makes it harder for new voices to join the discussion. To make it easier for people to join the discussion, Ken envisioned an innovative gateway into the boards based on a shifting graph of topics ranked by post date (x-axis) and number of responses (y-axis). This solution was inspired in part by “The Pool” — “a collaborative online environment for creating art, code, and texts” developed by Jon Ippolito at the University of Maine — in which ideas and project proposals float in different regions of a two-dimensional graph depending on quantity and tenor of feedback from the collective.

Returning to the book view, to push the boundaries of the blog form, we introduced a presentation format that uniquely fits around McKenzie’s book form—twenty-five regularly sized paragraphs in nine different chapters. Yes, each chapter has exactly 25 paragraphs, making mathematically consistent presentation possible (as an information designer I am elated at this systematic neatness). We decided on showing a cascade of five paragraphs, with one paragraph visible at a time, letting you navigate through chapters and then sets of five paragraphs within a chapter.

As a delightful aside, we started prototyping with a sheet of paper and index cards, but by some sideways luck we pulled out a deck of Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies cards, which suited our needs perfectly. The resulting paper prototype (photo w/ wireframe cues photoshop’d in):

This project has already provided us with a rich discussion regarding authorship and feedback. As we develop the prototypes we will undoubtedly have more questions, but also, hopefully, more solutions that help us redefine the edges and forms of digital discourse.

Ben Vershbow contributed to this post.

the value of voice

We were discussing some of the core ideas that circulate in the background of the Institute and flow in and around the projects we work on—Sophie, nexttext, Thinking Out Loud—and how they contrast with Wikipedia (and other open-content systems). We seem obsessed with Wikipedia, I know, but it presents us with so many points to contrast with traditional styles of authorship and authority. Normally we’d make a case for Wikipedia, the quality of content derived from mass input, and the philosophical benefits of openness. Now though, I’d like to step back just a little ways and make a case for the value of voice.

Presumably the proliferation of blogs and self-publishing indicates that the cultural value of voice is not in any danger of being swallowed by collaborative mass publishing. On the other hand, the momentum surrounding open content and automatic recombination is discernibly mounting to challenge the author’s historically valued perch.

I just want to note that voice is not the same as authority. We’ve written about the crossover between authorship and authority here, here, and here. But what we talked about yesterday was not authority—rather, it was a discussion about the different ethos that a work has when it is imbued with a recognizable voice.

Whether the devices employed are thematic, formal, or linguistic, the individual crafts a work that is centripetal, drawing together in your mind even if the content is wide-ranging. This is the voice, the persona that enlivens pages of text with feeling. At an emotional level, the voice is the invisible part of the work that we identify and connect with. At a higher level, voice is the natural result of the work an author has put effort into researching and collating the information.

Open systems naturally struggle to develop the singular voice of highly authored work. An open system’s progress relies on rules to manage the continual process of integrating content written by different contributors. This gives open works a mechanical sensibility, which works best with fact-based writing and a neutral point of view. Wikipedia, as a product, has a high median standard for quality. But that quality is derived at the expense of distinctive voices.

This is not to say that Wikipedia is without voice. I think most people would recognize a Wikipedia article (or, really, any encyclopedia article) by its broad brush strokes and purposeful disengagement with the subject matter. And this is the fundamental point of divide. An individual’s work is in intimate dialogue with the subject matter and the reader. The voice is the unique personality in the work.

Both approaches are important, and we at the Institute hope to navigate the territory between them by helping authors create texts equipped for openness, by exploring boundaries of authorship, and by enabling discourse between authors and audiences in a virtuous circle. We encourage openness, and we like it. But we cannot underestimate the enduring value of individual voice in the infinite digital space.

fair use and the networked book

I just finished reading the Brennan Center for Justice’s report on fair use. This public policy report was funded in part by the Free Expression Policy Project and describes, in frightening detail, the state of public knowledge regarding fair use today. The problem is that the legal definition of fair use is hard to pin down. Here are the four factors that the courts use to determine fair use:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

From Dysfunctional Family Circus, a parody of the Family Circus cartoons. Find more details at illegal-art.org

Unfortunately, these criteria are open to interpretation at every turn, and have provided little with which to predict any judicial ruling on fair use. In a lawsuit, no one is sure of the outcome of their claim. This causes confusion and fear for individuals and publishers, academics and their institutions. In many cases where there is a clear fair use argument, the target of copyright infringement action (cease and desist, lawsuit) does not challenge the decision, usually for financial reasons. It’s just as clear that copyright owners pursue the protection of copyright incorrectly, with plenty of misapprehension about what qualifies for fair use. The current copyright law, as it has been written and upheld, is fraught with opportunities for mistakes by both parties, which has led to an underutilization of cultural assets for critical, educational, or artistic purposes. Larry Sanger posted this comment to if:book’s recent Digital Universe and expert review post. In the second paragraph Sanger suggests that experts should not have to constantly prove the value of their expertise. We think this is a crucial question. What do you think? The notion of expert review has been tossed around in the open-content community for a long time. Philosophically, those who lean towards openness tend to sneer at the idea of formalized expert review, trusting in the multiplied consciousness of the community to maintain high standards through less formal processes. Wikipedia is obviously the most successful project in this mode.The informal process has the benefit of speed, and avoids bureaucracy—something which raises the barrier to entry, and keeps out people who just don’t have the time to deal with ‘process.’ You can think of the Digital Universe as a set of portals, each defined by a topic, such as the planet Mars. And from each portal, there will be links to the best resources on the Web, including a lot of resources of different kinds that are prepared by experts and the general public under the management of experts. This will include an encyclopedia, as well as public domain books, participatory journalism, forums of various kinds and so forth. We’ll build a community of experts and an online collaborative network of independent organizations, each of which has authority over its own discipline to select material and to build resources that are together displayed through a single free-information platform. I have experience with the editor model from my time at About.com. The About.com model is based on ‘guides’—nominal (and sometimes actual) experts on a chosen topic (say NASCAR, or anesthesiology)—who scour the internet, find good resources, and write articles and newsletters to facilitate understanding and keep communities up to date. The guides were overseen by a bevy of editors, who tended mostly to enforce the quotas for newsletters and set the line on quality. About.com has its problems, but it was novel and successful during its time. Hi. I’m Jesse, the latest member to join the staff here at the Institute. I’m interested in network effects, online communities, and emergent behavior. Right now I’m interested in the tools we have available to control and manipulate RSS feeds. My goal is to collect a wide variety of feeds and tease out the threads that are important to me. In my experience, mechanical aggregation gives you quantity and diversity, but not quality and focus. So I did a quick investigation of the tools that exist to manage and manipulate feeds.

This restrictive atmosphere is even more prevalent in the film and music industries. The RIAA lawsuits are a well-known example of the industry protecting its assets via heavy-handed lawsuits. The culture of shared use in the movie industry is even more stifling. This combination of aggressive control by the studio and equally aggressive piracy is causing a legislative backlash that favors copyright holders at the expense of consumer value. The Brennan report points to several examples where the erosion of fair use has limited the ability of scholars and critics to comment on these audio/visual materials, even though they are part of the landscape of our culture.

That’s why

This entry was posted in brennan_center, copyright, Copyright and Copyleft, creative_commons, fair_use, law, open_content and tagged fair_use copyright brennan_center creative_commons open_content law on .

who do you trust?

“In its first year or two it was very much not the case that Wikipedia “only looks at reputation that has been built up within Wikipedia.” We used to show respect to well-qualified people as soon as they showed up. In fact, it’s very sad that it has changed in that way, because that means that Wikipedia has become insular–and it has, too. (And in fact, I warned very specifically against this insularity. I knew it would rear its ugly head unless we worked against it.) Worse, Wikipedia’s notion of expertise depends on how well you work within that system–which has nothing whatsoever to do with how well you know a subject.

“That’s what expertise is, after all: knowing a lot about a subject. It seems that any project in which you have to “prove” that you know a lot about a subject, to people who don’t know a lot about the subject, will endlessly struggle to attract society’s knowledge leaders.”

digital universe and expert review

The other side of that coin is the belief that experts and editors encourage civil discourse at a high level; without them you’ll end up with mob rule and lowest common denominator content. Editors encourage higher quality writing and thinking. Thinking and writing better than others is, in a way, the definition of expert. In addition, editors and experts tend to have a professional interest in the subject matter, as well as access to better resources. These are exactly the kind of people who are not discouraged by higher barriers to entry, and they are, by extension, the people that you want to create content on your site.

Larry Sanger thinks that, anyway. A Wikipedia co-founder, he gave an interview on news.com about a project that plans to create a better Wikipedia, using a combination of open content development and editorial review: The Digital Universe.

The Digital Universe model is an improvement on the single guide model; it encourages a multitude of people to contribute to a reservoir of content. Measured by available resources, the Digital Universe model wins, hands down. As with all large, open systems, emergent behaviors will add even more to the system in ways than we cannot predict. The Digitial Universe will have it’s own identity and quality, which, according to the blueprint, will be further enhanced by expert editors, shaping the development of a topic and polishing it to a high gloss.

Full disclosure: I find the idea of experts “managing the public” somehow distasteful, but I am compelled by the argument that this will bring about a better product. Sanger’s essay on eliminating anti-elitism from Wikipedia clearly demonstrates his belief in the ‘expert’ methodology. I am willing to go along, mindful that we should be creating material that not only leads people to the best resources, but also allows them to engage more critically with the content. This is what experts do best. However, I’m pessimistic about experts mixing it up with the public. There are strong, and as I see it, opposing forces in play: an expert’s reputation vs. public participation, industry cant vs. plain speech, and one expert opinion vs. another.

The difference between Wikipedia and the Digital Universe comes down, fundamentally, to the importance placed on authority. We’ll see what shape the Digital Universe takes as the stresses of maintaining an authoritative process clashes with the anarchy of the online public. I think we’ll see that adopting authority as your rallying cry is a volatile position in a world of empowered authorship and a universe of alternative viewpoints.

useful rss

Sites like MetaFilter and Technorati skim the most popular topics in the blogosphere.  But what sort of tools exist to help us narrow our focus? There are two tools that we can use right now: tag searches/filtering, and keyword searching. Tag searches (on Technorati) and tag filtering (on Metafilter) drill down to specific areas, like “books” or “books and publishing.” A casual search on MetaFilter was a complete failure, but Technorati, with its combination of tags and keyword search results produced good material.

But what sort of tools exist to help us narrow our focus? There are two tools that we can use right now: tag searches/filtering, and keyword searching. Tag searches (on Technorati) and tag filtering (on Metafilter) drill down to specific areas, like “books” or “books and publishing.” A casual search on MetaFilter was a complete failure, but Technorati, with its combination of tags and keyword search results produced good material.

There is also the Google Blog search. As Google puts it, you can ‘find blogs on your favorite topics.’ PageRank works, so PageRank applied to blogs should work too. Unfortunately it results in too many pages that, while higher ranked in the whole set of the Internet, either fail to be on topic or exist outside of the desired sub-spheres of a topic. For example, I searched for “gourmet food” and found one of the premier food blogs on the fourth page, just below Carpundit. Google blog search fails here because it can’t get small enough to understand the relationships in the blogosphere, and relies more heavily on text retrieval algorithms that sabotage the results.

Finally, let’s talk about aggregators. There is more human involvement in selecting sites you’re interested in reading. This creates a personalized network of sites that are related, if only by your personal interest. The problem is, you get what they want to write about. Managing a large collection of feeds can be tiresome when you’re looking for specific information. Bloglines has a search function that allows you to find keywords inside your subscriptions, then treat that as a feed. This neatly combines hand-picked sources with keyword or tag harvesting. The result: a slice of from your trusted collection of authors about a specific topic.

What can we envision for the future of RSS? Affinity mapping and personalized recommendation systems could augment the tag/keyword search functionality to automatically generate a slice from a small network of trusted blogs. Automatic harvesting of whole swaths of linked entries for offline reading in a bounded hypertext environment. Reposting and remixing feed content on the fly based on text-processing algorithms. And we’ll have to deal with the dissolving identity and trust relationships that are a natural consequence of these innovations.