This weekend I watched a performance of Voyage, the first part of Tom Stoppard’s new trilogy, The Coast of Utopia. It’s pure Stoppard: erudition delivered in a crossfire of dialogue and movement, skipping through time like a smartly thrown stone.

It is the story of young Russian intellectuals—Michael Bakunin, Nickolai Stankevich, Vissarion Belinsky, Alexander Herzen, Ivan Turgenev, Nicholas Ogarev—discovering foreign philosophy during the time of Tsar Nicholas I (a particularly conservative government). The young men, driven by Bakunin (played by Ethan Hawke), investigate the philosophies of Kant, Schelling, Goethe, Fichte, and Hegel. Bakunin ferociously pursues each philosopher and sprays his new knowledge at everyone he knows—most significantly his four sisters. By sharing books, writing letters, and expounding during summer visits to the family home he becomes the main vector of change in their lives. This first play is as much about the sisters’ struggle to withstand the shifting currents of MIchael’s idealism as it is about the early days of Russian intellectualism, or the last days of slavery in Russia, or the collision between ideas and reality.

Stoppard weaves these different themes together so deftly you can hardly tell where one ends and another begins. More importantly, it’s difficult to see how you could have one absent the others. The first act of the play is set at Premukhino, the Bakunin family estate, over the course of seven years. A phalanx of ragged bodies is set in the background, behind a sheer scrim representing the serfs. Their presence is constant, menacing, but generally unobtrusive to the Bakunin family, as they go about their own tumults brought on by one thing or another that Michael has done. At times you forget the serfs are there, and then, suddenly, you’ll look up and see the staggered rows of ragged bodies and a sense of foreboding descends.

The second act is set in Moscow, during the same seven years. Stoppard rewinds time to show us how events in the city led to the disruptions at Premukhino. The action in the city is invested with a sense of urgency, where the young men verbally joust as they try to define their latest position with regard to the newest book they’ve read. Moscow is a hotbed of anti-tsarist sentiment and foreign idealism. The political tension is high, the sensation of fear and revolt bubbles just below the surface. But Moscow is also an incubator for love, and it is there we witness the first real contact between humans, not just the meeting of like minds.

The play is a tour of European philosophy in the 1800’s, and it is highly ambitious (something you could say about any 9-hour trilogy, I suppose). But it is, nevertheless, gripping stuff. Billy Crudup does an amazing turn as Belinsky, completely inhabiting the character and committing to the moment. Ethan Hawke was fine as Bakunin, though his insouciance had a Reality Bites mopiness that seemed out of place in a young man who was struggling to bring Mother Russia into the modern era. The performance in the second act was more balanced and more powerful.

Prior to seeing the play I was concerned that the first act of a trilogy would have a sense of being open in the way a cliffhanger is open. I was watching it with two visitors from out of town, and it is unlikely they’ll be able to return to see Shipwrecked or Salvage. I didn’t want them to leave with a sense of the work being unfinished. While the action is indeed open-ended, there is a very strong sense of closure at the end of the second act. It is more portentous than unfinished: there is war and exile and a nobleman at the end of his life, contemplating the loss of his son and the dissolution of his estate. It is a nod to the great Russian novels, but with the unfussy delivery that I recognize from other Stoppard plays.

One of the things I kept noticing during the performance was the presence of books. When Stankevich passed a book to Bakunin, I felt the transfer of knowledge. The play expresses ideal of what we think about at the Institute: books as vehicles for big ideas. There is a treatise waiting to be written about the view of literature defining a nation (explosively presented in a monologue from Belinsky). And there is, throughout, a very powerful sense that the printed word is vastly important. But there is also that sense of impending loss, which makes us question where we are today. Do we live in a world where idealism is lost, and where the gilt-edged books filled with new philosophies are no longer valued? Or is it the opposite? Do we live in a world where the book is doing better than ever, and idealism takes so many forms that it is unrecognizable?

Author Archives: jesse wilbur

two novels revisited

Near future science fiction is a reflexive art: the present embellished to the point of transformation that, in turn, influences how we envision, and eventually create our future. It is not accurate—far from it—but there is power in determining the vocabulary we use to discuss a future that seems possible, or even probable. I read Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash in 2000 and thought it was a great read back then. I was twenty-five, the internet was tanking, but the online games were going strong and the Metaverse seemed so close. The Metaverse is an avatar inhabited digital world—the Internet on ‘roids—with extremely high levels of interactivity enabled by the combination of vast computing power, 3-D tracking gloves (think Minority Report), directional headphones, and wraparound goggles that project a fully immersive experience in front of your eyes. This is the technophilic dream: a place where physicality matters less than the ability to manipulate the code. If you control the code, you can make your avatar do just about anything.

Now, five years later, I’ve reread Snow Crash. It continues to be relevant. The depiction of a fractured, corporatized society and of the gulf between rich and poor are more true now than they were five years ago. But there is a special resonance with one idea in particular: the Metaverse. The Metaverse is what many people dream the Internet will eventually become. The Metaverse is, as much as anything, a place to hang out. It’s also a place to buy ‘space’ to build a house, a place for ads to be thrown at you while you are ‘goggled in,’ a place for people to trade information. In 2000, in reality, you would have a blog and chat with your friends on AIM. It didn’t have the same presence as an avatar in the Metaverse, where facial features can communicate as much information as the voice transmission. Even games, like Everquest, didn’t have the same culture as the Metaverse, because they were games, with goals and advancement based on game rules. But now we have Second Life. Second Life isn’t about that—it is a social place. No goals. See and be seen. Make your avatar look the way you want. Buy and build. Sell and produce your own digital culture. Share pictures. Share your life. This is closer to the Metaverse than ever, but I hope that doesn’t mean we’ll get corporate franchise burbclaves as well. Well, at least any more than there already are.

I also reread The Diamond Age. This is a story about society in the age of nanotech and the power of traditional values in an environment of post-materialism. When everything is possible through nanotech, humanity retreats to fortresses of bygone tradition to give life structure and meaning. In the post-nation-state society described in the book, humans live in “phyles,” groups of people with like thoughts and values bound together by will and rules of society. Phyles are separated from each other by geography, wealth, and status; phyle borders are vigorously protected by visible and invisible defenders. This separation of groups by ideology seems especially pertinent in light of the continuing divergence of political affiliation in the US. We live in a politically bifurcated society; it is not difficult to draw parallels between the Red state/Blue state distinction, and the phyles of New Atlantis, Hindustani, and the Celestial Kingdom.

The story focuses on a girl, Nell, and her book, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. The Primer is her guide through a difficult and dangerous life. Her Primer is scientifically advanced enough that it would, if we had it today, appear to be magic. The Primer is aware of its surroundings, and aware of the girl’s position in the surroundings. It is capable of determining relationships and decorating them with the trappings of ‘story’. The Primer narrates the story using the voice of a distant actor, who is on call, connected through the media system (again, the Internet but so much more). The Primer answers any questions Nell asks, expounds and expands on any part of the story she is curious about until she fully satisfies her curiosity. It is a perpetually self-improving, self-generating networked storybook, with one important key: it requires a real human’s input to narrate the words that appear on the page. Without a human voice behind it, it doesn’t have enough emotion to hold a person’s interest. Even in a world of lighter than air buildings and nanosite generated islands, tech can’t figure out how to make a non-human voice convey delicate emotion.

There are common threads in the two novels that are crystal clear. Stephenson illluminates the near future with an ambivalent light. Society is fragile and prone to collapse. The network is likely to be monopolized and overrun with advertising. The social fabric, instead of being interwoven with multiethnic thread, will simply be a geographic patchwork of walled enclaves competing with each other. Corporations (minus governments) will be the ultimate rulers of the world—not just the economic part of it, but the cultural part as well. This is a future I don’t want to live in. And here is where Stephenson is doing us a service: by writing the narrative that leads to this future, he is giving us signs so that we can work against its development. Ultimately, his novels are about the power of human will to work through and above technology to forge meaning and relationships. And that’s a lesson that will always be relevant.

a book by any other name

Predicting the future is a fool’s errand, but it comforts me to look back on the past and see that some questions are important enough to revisit in each new age. In the 1996 collection The Future of the Book, edited by Geoffrey Nunberg, there are several essays that treat the same questions that we are concerned with now: how will reading change in the digital environment? What will be the form of digital texts? What role for the author? The reader?

Dan’s recent post provoked a range of commentary that clearly illustrates the ongoing status of the debate. Despite the fact that these questions were raised, and treated, more than a decade ago—and certainly even further back, in texts I am unaware of (please make recommendations)—their answers are still unknown, which makes their relevance undiminished. The discussion is necessary, as Gary Frost pointed out, because “we do not have a vernacular beyond synthetics such as blog or Wiki or live journal or listserv.” We haven’t developed a canonical term for this idea of a digital text that includes multimedia, that accretes other text and multimedia from the activity of the network. When you are working at the edges of technology, inventing new terms of art to try and explain and market your concept, the jargon production is fever pitched. But we just haven’t been exploring this question long enough to see what odd word will stick that can serve to separate the idea of a physical book, in all its permutations, from the notion of a networked book, in its unexplored mystery. It’s a fundamental direction of our research at the Institute, and the contributions from our community of readers continues to be instructive.

lapham’s quarterly, or “history rhymes”*

Lewis Lapham, journalist, public intellectual and editor emeritus of Harper’s Magazine, is working on a new journal that critically filters current events through the lens of history. It’s called Lapham’s Quarterly, and here’s how the idea works: take a current event, like the Israeli conflict in Lebanon, and a current topic, like the use of civilian homes to store weapons, and put them up against historical documents, like the letter between General Sherman and General Hood debating the placement of the city’s population before the Battle of Atlanta. Through the juxtaposition, a continuous line between our forgotten past and our incomprehensible now. The journal is constituted of a section “in the present tense”, a collection of relevant historical excerpts, and closing section that returns to the present. Contributing writers are asked to write not about what they think, but what they know. It’s a small way to counteract the spin of our relentlessly opinionated media culture.

We’ve been asked to develop an online companion to the journal, which leverages the particular values of the network: participation, collaboration, and filtering. The site will feed suggestions into the print journal and serve as a gathering point for the interested community. There is an obvious tension between tight editorial focus required for print and the multi-threaded pursuits of the online community, a difference that will be obvious between the publication and the networked community. The print journal will have a high quality finish that engenders reverence and appreciation. The website will have a currency that is constantly refreshed, as topics accrete new submissions. Ultimately, the cacophony of the masses may not suit the stateliness of print, but integrating public participation into the editorial process will effect the journal. What effect? Not sure, but it’s worth the exploration. A recent conversation with the editorial team again finds them as excited about as we are.

(a short list of related posts: [1] [2] [3]).

* “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes” —Mark Twain

the good life: part 1

The Van Alen Institute has organized an exhibition that explores new design and use of public space for recreation. The exhibition displays innovative designs for reimagined and reclaimed public spaces from various architects and urban planners. The projects are organized into five categories: The Connected City, the Cultural City, the 24-Hour City, the Fun City, and the Healthy City. As part of the exhibition, the Van Alen Institute has been holding weekly panel discussions about designing public space from international and local (NYC) perspectives. The participants have been high level partners in some of the most widely regarded architecture firms in NYC and the world. The questions and discussions afterwards, however, have proved to be the most interesting part; there have been questions about autonomy and conformity in public space, and how much of the new public space has been designed for safety, but little else. They have become ‘non-spaces’, and fail to support public needs for engagement, relaxation, and health.

This week their discussion will move away from the architectural and planning and into new technology. It will be interesting to see how technology supports and influences ideas of connectedness in a public place; while the value of connecting to others from a private, isolated space seems obvious, doing so from a public place seems less common and less intuitive than face-to-face interaction. The panel, including Christina Ray (responsible for the Conflux Festival ) and Nick Fortugno (Come Out & Play Festival), will present and discuss “The Wired City” at 6:30 pm on Wednesday, Sep. 27.

play the city

Urban gaming is growing in popularity in correlation with the ascendance of mobile devices. Many current games depend on an email or text messaging enabled phone; some of the latest are digital scavenger hunts where the camera phone is the weapon of choice. This weekend at the Come Out & Play Festival, hosted by EyeBeam, you’ll have a chance to play some of the newest games in your own back alley. While not all urban games require tech—some are just about taking advantage of the unique density of the urban environment—the games at CO&P are almost uniformly tech enabled, using mobile phones or projectors or even visits to Second Life as aspects of gameplay.

The Come Out & Play Festival is a street games fesitval dedicated to exploring new styles of games and play.The festival will feature games from the creators of I love bees, PacManhattan, Conqwest, Big Urban Game and more.From massive multi-player walk-in events to scavenger hunts to public play performances, the festival will give players and the public the chance to take part in a variety of different games. Come rediscover the city around you through play.Why street games? Why a street games festival, you ask? Fair questions. Well, we like innovative use of public space. We like games which make people interact in new ways. We like games that alter your perception of your surroundings. But most importantly, we think games are great way to have fun.

Like the Conflux Festival, Come Out & Play encourages us to use our shared urban spaces differently, unlimited by the conventions of that space. But rather than approach it from the perspective of an individual remaking the rules of public engagement, CO&P encourages a game mentality, where the individual (or team) works within a different set of highly prescriptive rules. These rules aren’t the usual rules of public space, which is what makes it fun. But they are the rules of the game, and they cannot be broken if you want to continue to participate. Urban gaming has some root in the thinking of the Situationists—particularly the notion of public, anarchic play—so it seems especially ironic that the play is so structured. Still, I anticipate all the regulations in the world won’t kill the fun this weekend, and the faint whiff of activism will add a pleasant flavor to the proceedings. I’m especially looking forward to Cruel 2 B Kind (if I can just figure out how to get my phone to use email), and the enormous Space Invaders projection (it uses the side of a building as the screen and your body as the defender ship).

NYTimes reader

[editor’s note: The New York Times released a new software reader. It is Windows only. No Mac compatibility at this time. We asked Christine Boese, of serendipit-e.com, to post her thoughts on the matter.]

I got this off another news clip service I’m on…

NYT Finally Creates a Readable Online Newspaper (Slate)

Jack Shafer: About six months ago, I canceled my New York Times subscription because I had found the newspaper’s redesigned Web site to be superior to the print Times. I’ve now abandoned the Web version for the New York Times Reader, a new computer edition that has entered general beta release.

I went around to try to sign up for it and get a look. I couldn’t, because the Times IT dept overlooked making its beta available for Macs. I scanned through the screenshots, tho, and the comments on the blog preview of features, sneek peek #1 and #2.

Jack Shafer isn’t exactly an expert in interactive design, so I don’t know if his endorsement means anything other than, "Gee whiz, here’s a neato new thing!".

My initial impressions are that it looks like the International Herald Tribune

with a horizontal orientation I just can’t stand (the Herald Tribune often requires horizontal scrolling, and it’s far easier to read the printable version of stories). Yes, I see there is a narrow screen screenshot, but I’m thinking more about the text flow nightmares this design must cause.

But I think I have bigger reservations about the entire concept behind the Times Reader beta.

Here’s just a summary of questions I’d want answered, if I were actually able to test the beta:

- How is re-creating a facsimile of a print newspaper online a step forward for interactive media? Is it really, or is it just a kind of "horseless carriage" retrenchment? Shafer talks about some non-print-like pages that tell you what you’ve read or haven’t read, to assist browsing and search, but notes that the archives are thin. I wonder if the Times "Most Popular" feature makes the cut.

- Code. The big deal here is that it uses Microsoft .NET and advancers on Vista technology. I smell a walled garden. Is this XML-compatible? RSS-enabled? Is it even in HTML code that can be easily copied and pasted? (Shafer’s piece says it can be, but I want to see for myself) W3 validated? Does its content management system have permalinks? How do bookmarks work?

- Hyperlinks. Will the text accomodate them? Will the Times use them? Or by anchoring themselves firmly in a "reader" technology, perhaps a completely web-independent application, is the Times trying to go beyond simply a code-walled garden and also create a strong CONTENT walled garden as well? Is this a variant of TimesSelect on speed?

- Audience. Presumably the Times has some research that shows a need to court its paper-bound print-loving audience to its online products by making the online products more like the print products.

- Usability and Design. I’ve already mentioned the Mac incompatiblity. What other usability and design issues are present in this Times Reader technology? I’ll leave that to people who actually get use it.

But my question about audience is this: is there a REASON to make heroic efforts to lure print readers online? Isn’t the bigger issue trying to keep print readers attached to print, so that the ad-driven print editions don’t have to go the way of the dinosaur? The online news audience is already massive, and (Pew, Poynter) studies show that during the recent wars, large numbers of people were turning away from traditional news providers and outlets to seek out other sources of information, particularly international information, on the Internet and with news feed readers (RSS/Atom).

So in a competitive online news landscape, the Times makes a strategic turn to become more like its print product? And this will lure large numbers of online news readers back exclusively to the Times exactly HOW? Especially if it is a walled garden that doesn’t integrate well into the Blogosphere or in RSS news feed readers?

People like Terry Heaton and other media consultants (Heaton has a terrific blog, if you haven’t found it yet) are going out and telling traditional news media outlets that they have to move more strongly into an environment of UNBOUND media, to make their products more maleable for an unbound Internet environment. It appears the Times is not a company that has purchased Heaton’s services lately.

From the screenshots I’ve seen, there seems to be very little functionality or interactive user-customizable features at all. I don’t know. Color me stupid, but my gut reaction is that this is nothing more than another variant of the exact PDF version of the paper that the Times put out, only perhaps with better text searching features and dynamic text flow (meaning I’d bet it is XML-based instead of PDF-based, only with some custom-built or Microsoft-blessed walled garden DTD).

You know, for the money the Times spent on this (and the experienced journalists the Times Group laid off this past year), I’d have thought the best use of resources for a big media company would be to develop a really KILLER RSS feed reader, one that finally gets over the usability threshold that keeps feed readers in "Blinking 12-land" for most casual Internet users.

I mean, I know there are a lot of good feed readers out there (I favor Bloglines myself), but have any of you tried to convert non-techie co-workers into using a feed reader lately? I can’t for the LIFE of me figure out why there’s so much resistance to something so purely wonderful and empowering, something I believe is clearly the killer app on par with the first Mosaic browser in 1993. But because feed readers caught on bottom up instead of top down, there’s not only usability problems for the broadest audiences, there’s also a void at the top of the technology industry, by companies that fail to catch on to the RSS vision, mainly because they didn’t think it up themselves.

some thoughts on mapping

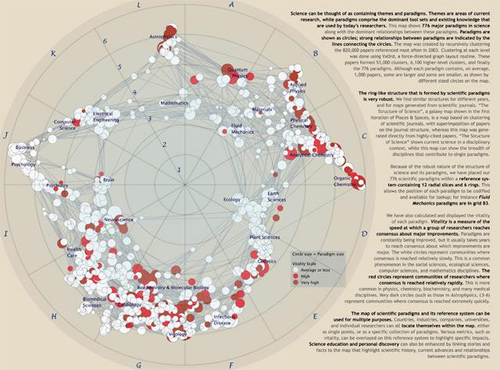

Mapping is a useful abstraction for exploring ideas, and not just for navigation through the physical world. A recent exhibit, Places & Spaces: Mapping Science, (at the New York Public Library of Science, Industry, and Business), presented maps that render the invisible path of scientific progress using metaphors of cartography. The maps ranged in innovation: there were several that imitated traditional geographical and topographical maps, while others created maps based on nodal presenation—tree maps and hyperbolic radial maps. Nearly all relied on citation analysis for the data points. Two interesting projects: Brad Paley’s TextArc Visualization of “The History of Science”, which maps scientific progress as described in the book “The History of Science”; and Ingo Gunther’s Worldprocessor Globes, which are perfectly idiosyncratic in their focus.

But, to me, the exhibit highlighted a fundamental drawback of maps. Every map is an incomplete view of an place or a space. The cartographer makes choices about what information to include, but more significantly, what information to leave out. Each map is a reflection of the cartographer’s point of view on the world in question.

Maps serve to guide—whether from home to a vacation house in the next state, or from the origin of genetic manipulation through to the current replication practices stem-cell research. In physical space, physical objects circumscribe your movement through that space. In mental space, those constraints are missing. How much more important is it, then, to trust your guide, and understand the motivations behind your map? I found myself thinking that mapping as a discipline has the same lack of transparency as traditional publishing.

How do we, in the spirit of exploration, maintain the useful art of mapping, yet expand and extend mapping for the networked age? The network is good at bringing information to people, and collecting feedback. A networked map would have elements of both information sharing, and information collection, in a live, updateable interface. Jeff Jarvis has discussed this idea already in his post on networked mapping. Jarvis proposes mashing up Google maps (or open street map) with other software to create local maps, by and for the community.

This is an excellent start (and I hope we’ll see integration of mapping tools in the near future), but does this address the limitations of cartographic editing? What I’m thinking about is something less like a Google map, and more like an emergent terrain assembled from ground-level and satellite photos, walks, contributed histories, and personal memories. Like the Gates Memory Project we did last year, this space would be derived from the aggregate, built entirely without the structural impositions of a predetermined map. It would have a Borgesian flavor; this derived place does not have to be entirely based on reality. It could include fantasies or false memories of a place, descriptions that only exists in dreams. True, creating a single view of such a map would come up against the same problems as other cartographic projects. But a digital map has the ability to reveal itself in layers (like old acetate overlays did for elevation, roads, and buildings). Wouldn’t it be interesting to see what a collective dreamscape of New York looked like? And then to peel back the layers down to the individual contributions? Instead of finding meaning through abstraction, we find meaningful patterns by sifting through the pile of activity.

We may never be able to collect maps of this scale and depth, but we will be able to see what a weekend of collective psychogeography can produce at the Conflux Festival, which opened yesterday in locations around NYC. The Conflux Festival (formerly the Psychogeography Festival) is “the annual New York festival for contemporary psychogeography, the investigation of everyday urban life through emerging artistic, technological and social practice.” It challenges notions of public and private space, and seeks out areas of exploration within and at the edges of our built environment. It also challenges us, as citizens, to be creative and engaged with the space we inhabit. With events going on in the city simultaneously at various locations, and a team of students from Carleton college recording them, I hope we’ll end up with a map composed of narrative as much as place. Presented as audio- and video-rich interactions within specific contexts and locations in the city, I think it will give us another way to think about mapping.

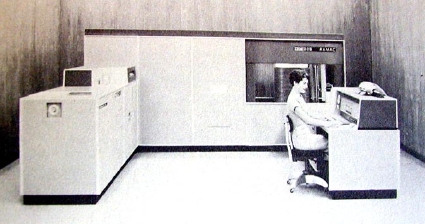

the march of technology

Sept. 13, 1956

IBM’s 5MegaByte hard drive, is the size of two refrigerators and costs $50,000.

Feb. 13, 2006

Seagate’s 12GigaByte hard drive, will fit in your cell phone.

Sept. 13, 2006

50 years later: 200 times more storage than the IBM drive on something smaller than a postage stamp. (Size: 11mm widex 15mm long x 1mm tall).

(thanks to endgadget)

book trailers, but no network

We often conceive of the network as a way to share culture without going through the traditional corporate media entities. The topology of the network is created out of the endpoints; that is where the value lies. This story in the NY Times prompted me to wonder: how long will it take media companies to see the value of the network?

The article describes a new marketing tool that publishers are putting into their marketing arsenal: the trailer. As in a movie trailer, or sometimes an informercial, or a DVD commentary track.

“The video formats vary as widely as the books being pitched. For well-known authors, the videos can be as wordy as they are visual. Bantam Dell, a unit of Random House, recently ran a series in which Dean Koontz told funny stories about the writing and editing process. And Scholastic has a video in the works for “Mommy?,” a pop-up book illustrated by Maurice Sendak that is set to reach stores in October. The video will feature Mr. Sendak against a background of the book’s pop-ups, discussing how he came up with his ideas for the book.”

Who can fault them for taking advantage of the Internet’s distribution capability? It’s cheap, and it reaches a vast audience, many of whom would never pick up the Book Review. In this day and age, it is one of the most cost effective methods of marketing to a wide audience. By changing the format of the ad from a straight marketing message to a more interesting video experience, the media companies hope to excite more attention for their new releases. “You won’t get young people to buy books by boring them to death with conventional ads,” said Jerome Kramer, editor in chief of The Book Standard.”

But I can’t help but notice that they are only working within the broadcast paradigm, where advertising, not interactivity, is still king. All of these forms (trailer, music video, infomercial) were designed for use with television; their appearance in the context of the Internet further reinforces the big media view of the ‘net as a one-way broadcast medium. A book is a naturally more interactive experience than watching a movie. Unconventional ads may bring more people to a product, but this approach ignores one of the primary values of reading. What if they took advantage of the network’s unique virtues? I don’t have the answers for this, but only an inkling that publishing companies would identify successes sooner and mitigate flops earlier, that the feedback from the public would benefit the bottom line, and that readers will be more engaged with the publishing industry. But the first step is recognizing that the network is more than a less expensive form of television.