…I realize I was over-hasty in dismissing the recent additions made since book scanning resumed earlier this month. True, many of the fine wines in the cellar are there only for the tasting, but the vintage stuff can be drunk freely, and there are already some wonderful 19th century titles, at this point mostly from Harvard. The surest way to find them is to search by date, or by title and date. Specify a date range in advanced search or simply enter, for example, “date: 1890” and a wealth of fully accessible texts comes up, any of which can be linked to from a syllabus. An astonishing resource for teachers and students.

The conclusion: Google Print really is shaping up to be a library, that is, of the world pre-1923 — the current line of demarcation between copyright and the public domain. It’s a stark reminder of how over-extended copyright is. Here’s an 1899 english printing of The Mahabharata:

A charming detail found on the following page is this old Harvard library stamp that got scanned along with the rest:

Author Archives: ben vershbow

blogging and beyond

Yesterday on Talking Points Memo, Josh Marshall drew back momentarily from the relentless news cycle to air a few meta thoughts on blogs and blogging, fleshing out some of the ideas behind his TPM Cafe venture (a multi-blog hub on politics and society) and his recent hiring notice for a “reporter-blogger” to cover Capitol Hill.

Marshall’s ruminations tie in nicely with a meeting the institute is holding tomorrow (I’m running to the airport shortly) at our institutional digs at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles to discuss possible futures of the blogging medium, particularly in regard to the academy and the role of public intellectual. Gathering around the table for a full day of discussion will be a number of blogger-professors and doctoral students, several journalists and journalism profs, and a few interesting miscellaneous spoons to help stir the pot. We’ve set up a blog (very much resembling this one) as a planning stage for the meeting. Feel free to take a look and comment on the agenda and the list of participants.

The meeting is a sort of brainstorm session for a project the institute is hatching that aims to encourage academics with expert knowledge and a distinctive voice to use blogs and other internet-based vehicles to step beyond the boundaries of the academy to reach out to a broader public audience. Issues/questions/problems we hope to address include the individual voice in conflict with (or in complement to) mainstream media. How the individual voice establishes and maintains integrity on the web. How several voices could be aggregated in a way that expands both the audience and the interaction with readers without sacrificing the independence of the individual voices. Blogging as a bridge medium between the academy and the world at large. Blogging as a bridge medium between disciplines in the academy in a way that sheds holistic light on issues of importance to a larger public. And strengths and weaknesses of the blog form itself.

This last point has been on our minds a lot lately and I hope it will get amply discussed at the meeting. A year or two ago, the word “blog” didn’t mean anything to most people. Now it is all but fully embraced as the medium of the web. But exciting as the change has been, it shouldn’t be assumed that blogs are the ideal tool for all kinds of discourse. In fact, what’s interesting about blogs right now, especially the more intellectually ambitious ones, is how much they are doing in so limiting a form. With its ruthlessly temporal structure and swift burial of anything more than 48 hours old, blogs work great for sites like TPM whose raison d’être is to comment on the news cycle, or sites like Boing Boing, Gawker, or Fark.com serving up oddities, gossip and boredom cures for the daily grind. But if, god forbid, you want ideas and discussion to unfold over time, and for writing to enjoy a more ample window of relevance, blogs are frustratingly limited.

Even Josh Marshall, a politics blogger who is served well by the form, wishes it could go deeper:

…the stories that interest me right now are a) the interconnected web of corruption scandals bubbling up out the reining Washington political machine and b) the upcoming mid-term elections.

I cover a little of both. And I’ve particularly tried to give some overview of the Abramoff story. But I’m never able to dig deeply enough into the stories or for a sustained enough period of time or to keep track of how all the different ones fit together. That’s a site I’d like to read every day — one that pieced together these different threads of public corruption for me, showed me how the different ones fit together (Abramoff with DeLay with Rove with the shenanigans at PBS and crony-fied bureaucracies like the one Michael Brown was overseeing at FEMA) and kept tabs on how they’re all playing in different congressional elections around the country.

That’s a site I’d like to read because I’m never able to keep up with all of it myself. So we’re going to try to create it.

I’m excited to hear from folks at tomorrow’s meeting where they’d like blogging to go. I’d like to think that we’re groping toward a new web genre, perhaps an extension of blogs, that is less temporal and more thematic — where ideas, not time, are the primary organizing factor. This question of form goes hand in hand with the content question that our meeting will hopefully address: how do we get more people with big ideas and expertise to start engaging the world in a serious way through these burgeoning forms? I could say more, but I’ve got a plane to catch.

more bad news for print news

These figures (scroll down) aren’t pretty, but keep in mind that they convey more than a simple flight of readership. Part of it is a conscious decision by newspapers to cut out costly promotional efforts and to re-focus on core circulation. But the overall trend, and the fact that the core is likely to shrink as it grows older, can’t be denied.

Things could change very suddenly if investors in the big newspaper conglomerates start demanding the sale or outright dismantling of print operations. The Los Angeles Times reported yesterday of pressure building at Knight Ridder Inc., where the more powerful shareholders, dismayed with the continued tumbling of stock values, seem to be urging things toward a reckoning, some even welcoming the idea of a hostile takeover. The Times: “…if shareholders force the sale or the dismantling of Knight Ridder, few in the newspaper industry expect the revolt to stop there.”

The pre-Baby Boom generation typically subscribed to several newspapers, something that changed when the Boomers came of age. While competition with the web may be a major factor in recent upheavals, there are generational tectonics at work as well, habits formed long ago that are only now expressing themselves in the marketplace. Even if newspapers start to phase out print and focus entirely on the web, the erosion is likely to continue. It’s not just the distribution model that changes, but the whole conceptual framework.

Ray, who just joined us here at the institute, was talking today about how online social networks are totally changing the way the younger generation gets its news. It’s much more about the network of friends, the circulation of news from diverse sources through the collective filter, and not about your trusted daily paper. So the whole idea of a centralized news organization is shifting and perhaps dissolving.

From the L.A. Times:

Average weekday circulation of the nation’s 20 biggest newspapers for the six-month period ended Sept. 30 and percentage change from a year earlier:

1. USA Today, 2,296,335, down 0.59%

2. Wall Street Journal, 2,083,660, down 1.1%

3. New York Times, 1,126,190, up 0.46%

4. Los Angeles Times, 843,432, down 3.79%

5. New York Daily News, 688,584, down 3.7%

6. Washington Post, 678,779, down 4.09%

7. New York Post, 662,681, down 1.74%

8. Chicago Tribune, 586,122, down 2.47%

9. Houston Chronicle, 521,419, down 6.01%*

10. Boston Globe, 414,225, down 8.25%

11. Arizona Republic, 411,043, down 0.54%*

12. Star-Ledger of Newark, N.J., 400,092, up 0.01%

13. San Francisco Chronicle, 391,681, down 16.4%*

14. Star Tribune of Minneapolis-St. Paul, 374,528, down 0.26%

15. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 362,426, down 8.73%

16. Philadelphia Inquirer, 357,679, down 3.16%

17. Detroit Free Press, 341,248, down 2.18%

18. Plain Dealer, Cleveland, 339,055, down 4.46%

19. Oregonian, Portland, 333,515, down 1.24%

20. San Diego Union-Tribune, 314,279, down 6.24%

no laptop left behind

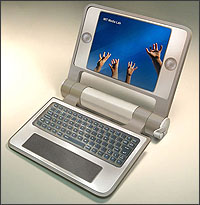

MIT has re-dubbed its $100 Laptop Project “One Laptop Per Child.” It’s probably a good sign that they’ve gotten children into the picture, but like many a program with sunny-sounding names and lofty goals, it may actually contain something less sweet. The hundred-dollar laptop is about bringing affordable computer technology to the developing world. But the focus so far has been almost entirely on the hardware, the packaging. Presumably what will fit into this fancy packaging is educational software, electronic textbooks and the like. But we aren’t hearing a whole lot about this. Nor are we hearing much about how teachers with little or no experience with computers will be able to make use of this powerful new tool.

MIT has re-dubbed its $100 Laptop Project “One Laptop Per Child.” It’s probably a good sign that they’ve gotten children into the picture, but like many a program with sunny-sounding names and lofty goals, it may actually contain something less sweet. The hundred-dollar laptop is about bringing affordable computer technology to the developing world. But the focus so far has been almost entirely on the hardware, the packaging. Presumably what will fit into this fancy packaging is educational software, electronic textbooks and the like. But we aren’t hearing a whole lot about this. Nor are we hearing much about how teachers with little or no experience with computers will be able to make use of this powerful new tool.

The headlines tell of a revolution in the making: “Crank It Up: Design of $100 Laptop for the World’s Children Unveiled” or “Argentina Joins MIT’s Low-Cost Laptop Plan: Ministry of Education is ordering between 500,000 to 1 million.” Conspicuously absent are headlines like “Web-Based Curriculum in Development For Hundred Dollar Laptops” or “Argentine Teachers Go On Tech Tutorial Retreats, Discuss Pros and Cons of Technology in the Classroom.”

Help! Help! We’re sinking!

This emphasis on the package, on the shell, makes me think of the Container Store. Anyone who has ever shopped at the Container Store knows that it is devoted entirely to empty things. Shelves, bins, baskets, boxes, jars, tubs, and crates. Empty vessels to organize and contain all the bric-a-brac, the creeping piles of crap that we accumulate in our lives. Shopping there is a weirdly existential affair. Passing through aisles of hollow objects, your mind filling them with uses, needs, pressing abundances. The store’s slogan “contain yourself” speaks volumes about a culture in the advanced stages of consumption-induced distress. The whole store is a cry for help! Or maybe a sedative. There’s no question that the Container Store sells useful things, providing solutions to a problem we undoubtedly have. But that’s just the point. We had to create the problem first.

I worry that One Laptop Per Child is providing a solution where there isn’t a problem. Open up the Container Store in Malawi and people there would scratch their heads. Who has so much crap that they need an entire superstore devoted to selling containers? Of course, there is no shortage of problems in these parts of the world. One need not bother listing them. But the hundred-dollar laptop won’t seek to solve these problems directly. It’s focused instead on a much grander (and vaguer) challenge: to bridge the “digital divide.” The digital divide — that catch-all bogey, the defeat of which would solve every problem in its wake. But beware of cure-all tonics. Beware of hucksters pulling into the dusty frontier town with a shiny new box promising to end all woe.

A more devastating analogy was recently drawn between MIT’s hundred dollar laptops and pharmaceutical companies peddling baby formula to the developing world, a move that has made the industries billions while spreading malnutrition and starvation.

Breastfeeding not only provides nutrition, but also provides immunity to the babies. Of course, for a baby whose mother cannot produce milk, formula is better than starvation. But often the mothers stop producing milk only after getting started on formula. The initial amount is given free to the mothers in the poor parts of the world and they are told that formula is much much better than breast milk. So when the free amount is over and the mother is no longer lactating, the formula has to be bought. Since it is expensive, soon the formula is severely diluted until the infant is receiving practically no nutrition and is slowly starving to death.

…Babies are important when it comes to profits for the peddlers of formula. But there are only so many babies in the developed world. For real profit, they have to tap into the babies of the under-developed world. All with the best of intentions, of course: to help the babies of the poor parts of the world because there is a “formula divide.” Why should only the rich “gain” from the wonderful benefits of baby formula?

Which brings us back to laptops:

Hundreds of millions of dollars which could have been more useful in providing primary education would instead end up in the pockets of hardware manufacturers and software giants. Sure a few children will become computer-savvy, but the cost of this will be borne by the millions of children who will suffer from a lack of education.

Ethan Zuckerman, a passionate advocate for bringing technology to the margins, was recently able to corner hundred-dollar laptop project director Nicholas Negroponte for a couple of hours and got some details on what is going on. He talks at great length here about the design of the laptop itself, from the monitor to the hand crank to the rubber gasket rim, and further down he touches briefly on some of the software being developed for it, including Alan Kay’s Squeak environment, which allows children to build their own electronic toys and games.

The open source movement is behind One Laptop Per Child in a big way, and with them comes the belief that if you give the kids tools, they will teach themselves and grope their way to success. It’s a lovely thought, and may prove true in some instances. But nothing can substitute for a good teacher. Or a good text. It’s easy to think dreamy thoughts about technology emptied of content — ready, like those aisles of containers, drawers and crates, to be filled with our hopes and anxieties, to be filled with little brown hands reaching for the stars. But that’s too easy. And more than a little dangerous.

Dropping cheap, well-designed laptops into disadvantaged classrooms around the world may make a lot of money for the manufacturers and earn brownie points for governments. And it’s a great feel-good story for everyone in the thousand-dollar laptop West. But it could make a mess on the ground.

pages á la carte

The New York Times reports on programs being developed by both Amazon and Google that would allow readers to purchase online access to specific sections of books — say, a single recipe from a cookbook, an individual chapter from a how-to manual, or a particular short story or poem from an anthology. Such a system would effectively “unbind” books into modular units that consumers patch into their online reading, just as iTunes blew apart the integrity of the album and made digital music all about playlists. We become scrapbook artists.

It seems Random House is in on this too, developing a micropayment model and consulting closely with the two internet giants. Pages would sell for anywhere between five and 25 cents each.

google print’s not-so-public domain

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

The problem is, there really isn’t all that much there. Google’s gotten a lot of bad press for its supposedly cavalier attitude toward copyright, but spend a few minutes browsing Google Print and you’ll see just how publisher-centric the whole affair is. The idea of a text being in the public domain really doesn’t amount to much if you’re only talking about antique manuscripts, and these are the only books that they’ve made fully accessible. Daisy Miller‘s copyright expired long ago but, with the exception of Harvard’s illustrated 1892 copy, all the available scanned editions are owned by modern publishers and are therefore only snippeted. This is not an online library, it’s a marketing program. Google Print will undeniably have its uses, but we shouldn’t confuse it with a library.

(An interesting offering from the stacks of the New York Public Library is this mid-19th century biographic registry of the wealthy burghers of New York: “Capitalists whose wealth is estimated at one hundred thousand dollars and upwards…”)

electronic literature collection – call for works

The Electronic Literature Organization seeks submissions for the first Electronic Literature Collection. We invite the submission of literary works that take advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the computer. Works will be accepted until January 31, 2006. Up to three works per author will be considered.

The Electronic Literature Collection will be an annual publication of current and older electronic literature in a form suitable for individual, public library, and classroom use. The publication will be made available both online, where it will be available for download for free, and as a packaged, cross-platform CD-ROM, in a case appropriate for library processing, marking, and distribution. The contents of the Collection will be offered under a Creative Commons license so that libraries and educational institutions will be allowed to duplicate and install works and individuals will be free to share the disc with others.

The editorial collective for the first volume of the Electronic Literature Collection, to be published in 2006, is:

N. Katherine Hayles

Nick Montfort

Scott Rettberg

Stephanie Strickland

Go here for full submission guidelines.

wikipedia hard copy

Believe it or not, they’re printing out Wikipedia, or rather, sections of it. Books for the developing world. Funny that just days ago Gary remarked:

“A Better Wikipedia will require a print version…. A print version would, for better or worse, establish Wikipedia as a cosmology of information and as a work presenting a state of knowledge.”

Prescient.

the creeping (digital) death of fair use

Meant to post about this last week but it got lost in the shuffle… In case anyone missed it, Tarleton Gillespie of Cornell has published a good piece in Inside Higher Ed about how sneaky settings in course management software are effectively eating away at fair use rights in the academy. Public debate tends to focus on the music and movie industries and the ever more fiendish anti-piracy restrictions they build into their products (the latest being the horrendous “analog hole”). But a similar thing is going on in education and it is decidely under-discussed.

Gillespie draws our attention to the “Copyright Permissions Building Block,” a new add-on for the Blackboard course management platform that automatically obtains copyright clearances for any materials a teacher puts into the system. It’s billed as a time-saver, a friendly chauffeur to guide you through the confounding back alleys of copyright.

But is it necessary? Gillespie, for one, is concerned that this streamlining mechanism encourages permission-seeking that isn’t really required, that teachers should just invoke fair use. To be sure, a good many instructors never bother with permissions anyway, but if they stop to think about it, they probably feel that they are doing something wrong. Blackboard, by sneakily making permissions-seeking the default, plays to this misplaced guilt, lulling teachers away from awareness of their essential rights. It’s a disturbing trend, since a right not sufficiently excercised is likely to wither away.

Fair use is what oxygenates the bloodstream of education, allowing ideas to be ideas, not commodities. Universities, and their primary fair use organs, libraries, shouldn’t be subjected to the same extortionist policies of the mainstream copyright regime, which, like some corrupt local construction authority, requires dozens of permits to set up a simple grocery store. Fair use was written explicitly into law in 1976 to guarantee protection. But the market tends to find a way, and code is its latest, and most insidious, weapon.

Amazingly, few academics are speaking out. John Holbo, writing on The Valve, wonders:

Why aren’t academics – in the humanities in particular – more exercised by recent developments in copyright law? Specifically, why aren’t they outraged by the prospect of indefinite copyright extension?…

…It seems to me odd, not because overextended copyright is the most pressing issue in 2005 but because it seems like a social/cultural/political/economic issue that recommends itself as well suited to be taken up by academics – starting with the fact that it is right here on their professional doorstep…

Most obviously on the doorstep is Google, currently mired in legal unpleasantness for its book-scanning ambitions and the controversial interpretation of fair use that undergirds them. Why aren’t the universities making a clearer statement about this? In defense? In concern? Soon, when search engines move in earnest into video and sound, the shit will really hit the fan. The academy should be preparing for this, staking out ground for the healthy development of multimedia scholarship and literature that necessitates quotation from other “texts” such as film, television and music, and for which these searchable archives will be an essential resource.

Fair use seems to be shrinking at just the moment it should be expanding, yet few are speaking out.

a better wikipedia will require a better conversation

There’s an interesting discussion going on right now under Kim’s Wikibooks post about how an open source model might be made to work for the creation of authoritative knowledge — textbooks, encyclopedias etc. A couple of weeks ago there was some dicussion here about an article that, among other things, took some rather cheap shots at Wikipedia, quoting (very selectively) a couple of shoddy passages. Clearly, the wide-open model of Wikipedia presents some problems, but considering the advantages it presents (at least in potential) — never out of date, interconnected, universally accessible, bringing in voices from the margins — critics are wrong to dismiss it out of hand. Holding up specific passages for critique is like shooting fish in a barrel. Even Wikipedia’s directors admit that most of the content right now is of middling quality, some of it downright awful. It doesn’t then follow to say that the whole project is bunk. That’s a bit like expelling an entire kindergarten for poor spelling. Wikipedia is at an early stage of development. Things take time.

Instead we should be talking about possible directions in which it might go, and how it might be improved. Dan for one, is concerned about the market (excerpted from comments):

What I worry about…is that we’re tearing down the old hierarchies and leaving a vacuum in their wake…. The problem with this sort of vacuum, I think, is that capitalism tends to swoop in, simply because there are more resources on that side….

…I’m not entirely sure if the world of knowledge functions analogously, but Wikipedia does presume the same sort of tabula rasa. The world’s not flat: it tilts precariously if you’ve got the cash. There’s something in the back of my mind that suspects that Wikipedia’s not protected against this – it’s kind of in the state right now that the Web as a whole was in 1995 before the corporate world had discovered it. If Wikipedia follows the model of the web, capitalism will be sweeping in shortly.

Unless… the experts swoop in first. Wikipedia is part of a foundation, so it’s not exactly just bobbing in the open seas waiting to be swept away. If enough academics and librarians started knocking on the door saying, hey, we’d like to participate, then perhaps Wikipedia (and Wikibooks) would kick up to the next level. Inevitably, these newcomers would insist on setting up some new vetting mechanisms and a few useful hierarchies that would help ensure quality. What would these be? That’s exactly the kind of thing we should be discussing.

The Guardian ran a nice piece earlier this week in which they asked several “experts” to evaluate a Wikipedia article on their particular subject. They all more or less agreed that, while what’s up there is not insubstantial, there’s still a long way to go. The biggest challenge then, it seems to me, is to get these sorts of folks to give Wikipedia more than just a passing glance. To actually get them involved.

For this to really work, however, another group needs to get involved: the users. That might sound strange, since millions of people write, edit and use Wikipedia, but I would venture that most are not willing to rely on it as a bedrock source. No doubt, it’s incredibly useful to get a basic sense of a subject. Bloggers (including this one) link to it all the time — it’s like the conversational equivalent of a reference work. And for certain subjects, like computer technology and pop culture, it’s actually pretty solid. But that hits on the problem right there. Wikipedia, even at its best, has not gained the confidence of the general reader. And though the Wikimaniacs would be loathe to admit it, this probably has something to do with its core philosophy.

Karen G. Schneider, a librarian who has done a lot of thinking about these questions, puts it nicely:

Wikipedia has a tagline on its main page: “the free-content encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” That’s an intriguing revelation. What are the selling points of Wikipedia? It’s free (free is good, whether you mean no-cost or freely-accessible). That’s an idea librarians can connect with; in this country alone we’ve spent over a century connecting people with ideas.

However, the rest of the tagline demonstrates a problem with Wikipedia. Marketing this tool as a resource “anyone can edit” is a pitch oriented at its creators and maintainers, not the broader world of users. It’s the opposite of Ranganathan’s First Law, “books are for use.” Ranganathan wasn’t writing in the abstract; he was referring to a tendency in some people to fetishize the information source itself and lose sight that ultimately, information does not exist to please and amuse its creators or curators; as a common good, information can only be assessed in context of the needs of its users.

I think we are all in need of a good Wikipedia, since in the long run it might be all we’ve got. And I’m in now way opposed to its spirit of openness and transparency (I think the preservation of version histories is a fascinating element and one which should be explored further — perhaps the encyclopedia of the future can encompass multiple versions of the “the truth”). But that exhilarating throwing open of the doors should be tempered with caution and with an embrace of the parts of the old system that work. Not everything need be thrown away in our rush to explore the new. Some people know more than other people. Some editors have better judgement than others. There is such a thing as a good kind of gatekeeping.

If these two impulses could be brought into constructive dialogue then we might get somewhere. This is exactly the kind of conversation the Wikimedia Foundation should be trying to foster.