Since the release of the Sony Reader, I’ve been thinking a lot about the difference between digital text and digital music, and why an ebook device is not, as much as publishers would like it to be, an iPod. This is not an argument over the complexity of literature versus the complexity of music, rather it is a question of interfaces. It seems to me that reading interfaces are much more complicated than listening ones.

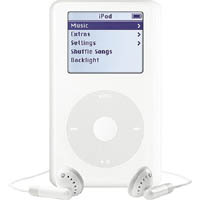

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.

A sequence of smooth thumb gestures leads to the desired track. Once the track has commenced, the device is tucked away into a pocket or knapsack, and the music takes over. That’s the simplicity of the iPod. Reading devices, on the other hand — whether paperback, web page or specialized ebook hardware — are felt and perceived throughout the reading experience. The text, the visual design, and the reader’s movement through them are all in constant interaction. So the device necessarily must be more complex.

In other words, a book — even a digital one — is something you have to “handle” in order to process its contents. The question Sony should be asking is what handling a book should mean in a digital, networked context? Obviously, it’s something very different than in print.

Another thing about portable music players from Walkmen to iPods is that music, in its infinite variety, can be delivered to the senses through a uniform channel: from the player, through the wire, to the ear. Again, with books it’s not so simple. Different books have different looks, and with good reason: they are visual media. This is something we tend to forget because we so strongly associate books with intangible things like stories and abstract ideas. But writing is a manipulation of visual symbols, and reading is something we do with our eyes. So well-considered visual design, of both documents and devices, is crucial — as much for electronic documents as for print ones.

Publishers want their ipod, a simple gadget locked into a content channel (like iTunes), but they’re going to have to do a lot better than the Sony Reader. To date, the web has done a much better job at fostering a wide variety of reading forms, primitive as they may still be, than any specialized ebook device or ebook format. A hard drive with ear phones may work for music, but a hard drive (and a pitifully small one at that) with an e-ink screen won’t be sufficient for books.

Monthly Archives: October 2006

google and the future of print

Veteran editor and publisher Jason Epstein, the man who first introduced paperbacks to American readers, discusses recent Google-related books (John Battelle, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, David Vise etc.) in the New York Review, and takes the opportunity to promote his own vision for the future of publishing. As if to reassure the Updikes of the world, Epstein insists that the “sparkling cloud of snippets” unleashed by Google’s mass digitization of libraries will, in combination with a radically decentralized print-on-demand infrastructure, guarantee a bright future for paper books:

[Google cofounder Larry] Page’s original conception for Google Book Search seems to have been that books, like the manuals he needed in high school, are data mines which users can search as they search the Web. But most books, unlike manuals, dictionaries, almanacs, cookbooks, scholarly journals, student trots, and so on, cannot be adequately represented by Googling such subjects as Achilles/wrath or Othello/jealousy or Ahab/whales. The Iliad, the plays of Shakespeare, Moby-Dick are themselves information to be read and pondered in their entirety. As digitization and its long tail adjust to the norms of human nature this misconception will cure itself as will the related error that books transmitted electronically will necessarily be read on electronic devices.

Epstein predicts that in the near future nearly all books will be located and accessed through a universal digital library (such as Google and its competitors are building), and, when desired, delivered directly to readers around the world — made to order, one at a time — through printing machines no bigger than a Xerox copier or ATM, which you’ll find at your local library or Kinkos, or maybe eventually in your home.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Epstein has founded a new company, OnDemand Books, to realize this vision, and earlier this year, they installed test versions of the new “Espresso Book Machine” (pictured) — capable of producing a trade paperback in ten minutes — at the World Bank in Washington and (with no small measure of symbolism) at the Library of Alexandria in Egypt.

Epstein is confident that, with a print publishing system as distributed and (nearly) instantaneous as the internet, the codex book will persist as the dominant reading mode far into the digital age.