HiddenHistory on Vimeo

Ben’s post last week on the darker side of flash shone like a light bulb. I’d spent the morning manipulating a scanned image of Ditr Roth, by taking this video clip from Vimeo and downloading the source quicktime (which Vimeo allows you to do) importing that into i-movie and exporting thirteen still images as jpegs to sequence into an animated gif. Then I started pulling wav. files off cds and layering tracks and looping them and turning them into mpegs. In other words, it was a day like any other, but when I read Social Powerpoint, I considered how many little media format borders I’d just crossed and how many times I cross those borders on any given day in any given post and how much I take that freedom for granted. So, is flash like that damn wall they keep threatening to build in Texas, or built once in Germany and before that in China (and as a bird, or a bowerbird knows….walls never really work if you can fly over them, or go around)?

I don’t know enough about flash coding, but I worry that these walls are all already there in the very way that people read different media. In the way that their eyeballs see them and their earballs hear them. A photograph and a drawing will both appear on a digital page as jpegs, but it still seems a little tricky to get people to look at them in relation to each other. In painting, you take two paintings and put them side by side: BANG, you have a diptych. It becomes a third thing. I thought that logic would translate very easily to a still image and a moving one, or a sound and word, but It seems that people like compartments. They like to have their still photos at flickr and their video on You tube and their music on i-tunes, and their book on tape as a podcast, etc. If things appear on a digital page together, they are meant to be surrounded by a trompe l’oeil metallic players just so that there’s no aesthetic miscegenation going on. It’s what we’re used to.

I tend to use a bunch of media sharing services for IT IN place both as a way to host media and as a way of advertising. One of the realities I’ve come to deal with is that many more people are going to see my work as discrete media objects on flickr and vimeo than will ever make it to the blog to read these things together in the way that I intended. People seem to get something out of the picutres and the videos as pictures and videos, etc., but I always feel they are missing half the point. I think of it as reading sentence fragments, or stanzas and never seeing the whole poem.

At this point, each media is like a different language and trying to put them all together into a single whole is a Wasteland exercise… and the wasteland is patrolled by Minutemen and snakes.

Maybe, in some ways throwing these fragments out into the digital desert is part of the poetry. Maybe the networked landscape offers the thrill of archeology for the reader, like digging up little photo, sound, and video tiles that lead the reader on to find the mosaic. Today someone left a comment on flickr:

“your pieces are like secret boxes.. when i click the link it’s like lifting a lid and inside there is always something surprisingly ‘other’ and beautiful..”

….I could tack a hundred paintings on a hundred walls and never get a such a nice sentence in return.

But then there is the voice of my mother and also the significant other saying, “So how do you make money?”

It’s important to point out that for me the nexus of meaning is in mark making (wether as writing, or drawing which I think are intimately and evolutionarily (?) cave connected). My practice always revolves around drawing… All the different media I use are like a series of mirrors that multiply all the possible ways to see and understand things, but as an art animal, my primary way of knowing where I stand in the funhouse is to make a mark and so I think my practice revolves around the drawings… they are the map, if you will. While not exactly having any sort of business model, I always figured digital media would lead people to want to see and maybe own the “original” drawings and paintings. Of course, I thought of it this way, because that’s just what people traditionally have done: they sell things to people who collect things. It’s what we’re used to.

Maybe the past few months of deciphering fluxus history (and it’s anti-art leanings) has put the zap on my head, but lately I’m a bit lost in a Labyrinth of my own creation. The blog has sort of become the work of art and none of it’s discrete parts (read media) are more or less important…not when I’m successful in a post. It may be Greek and Latin and French and German and English and Japanese, but it has to be read together if you want to get the jokes. I don’t know… maybe I’m speaking in tongues. I have a feeling the youtube generation will be malf blahming flah wast di blamspoontoop dang glover….

* addendum: as I wrote this, three people on flickr enquired about buying work.

– my Flickr page

– my Vimeo page

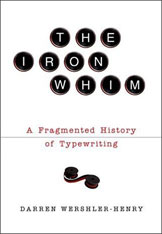

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a  A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise:

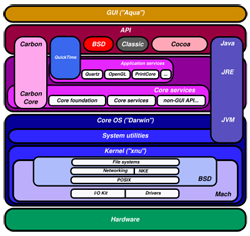

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise:  There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.