Open Source’s hour on the Googlization of libraries was refreshingly light on the copyright issue and heavier on questions about research, reading, the value of libraries, and the public interest. With its book-scanning project, Google is a private company taking on the responsibilities of a public utility, and Siva Vaidhyanathan came down hard on one of the company’s chief legal reps for the mystery shrouding their operations (scanning technology, algorithms and ranking system are all kept secret). The rep reasonably replied that Google is not the only digitization project in town and that none of its library partnerships are exclusive. But most of his points were pretty obvious PR boilerplate about Google’s altruism and gosh darn love of books. Hearing the counsel’s slick defense, your gut tells you it’s right to be suspicious of Google and to keep demanding more transparency, clearer privacy standards and so on. If we’re going to let this much information come into the hands of one corporation, we need to be very active watchdogs.

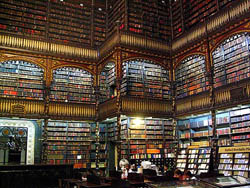

Our friend Karen Schneider then joined the fray and as usual brought her sage librarian’s perspective. She’s thrilled by the possibilities of Google Book Search, seeing as it solves the fundamental problem of library science: that you can only search the metadata, not the texts themselves. But her enthusiasm is tempered by concerns about privatization similar to Siva’s and a conviction that a research service like Google can never replace good librarianship and good physical libraries. She also took issue with the fact that Book Search doesn’t link to other library-related search services like Open Worldcat. She has her own wrap-up of the show on her blog.

Rounding out the discussion was Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, a cybertext studies blogger and professor of english at the University of Maryland. Kirschenbaum addressed the question of how Google, and the web in general, might be changing, possibly eroding, our reading practices. He nicely put the question in perspective, suggesting that scattershot, inter-textual, “snippety” reading is in fact the older kind of reading, and that the idea of sustained, deeply immersed involvement with a single text is largely a romantic notion tied to the rise of the novel in the 18th century.

A satisfying hour, all in all, of the sort we should be having more often. It was fun brainstorming with Brendan Greeley, the Open Source on “blogger-in-chief,” on how to put the show together. Their whole bit about reaching out to the blogosphere for ideas and inspiration isn’t just talk. They put their money where their mouth is. I’ll link to the podcast when it becomes available.

image: Real Gabinete Português de Literatura, Rio de Janeiro – Claudio Lara via Flickr

Monthly Archives: December 2005

thinking about google books: tonight at 7 on radio open source

While visiting the Experimental Television Center in upstate New York this past weekend, Lisa found a wonderful relic in a used book shop in Owego, NY — a small, leatherbound volume from 1962 entitled “Computers,” which IBM used to give out as a complimentary item. An introductory note on the opening page reads:

The machines do not think — but they are one of the greatest aids to the men who do think ever invented! Calculations which would take men thousands of hours — sometimes thousands of years — to perform can be handled in moments, freeing scientists, technicians, engineers, businessmen, and strategists to think about using the results.

This echoes Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 essay on computing and networked knowledge, “As We May Think”, which more or less prefigured the internet, web search, and now, the migration of print libraries to the world wide web. Google Book Search opens up fantastic possibilities for research and accessibility, enabling readers to find in seconds what before might have taken them hours, days or weeks. Yet it also promises to transform the very way we conceive of books and libraries, shaking the foundations of major institutions. Will making books searchable online give us more time to think about the results of our research, or will it change the entire way we think? By putting whole books online do we begin the steady process of disintegrating the idea of the book as a bounded whole and not just a sequence of text in a massive database?

The debate thus far has focused too much on the legal ramifications — helped in part by a couple of high-profile lawsuits from authors and publishers — failing to take into consideration the larger cognitive, cultural and institutional questions. Those questions will hopefully be given ample air time tonight on Radio Open Source.

Tune in at 7pm ET on local public radio or stream live over the web. The show will also be available later in the week as a podcast.

more on wikipedia

As summarized by a Dec. 5 article in CNET, last week was a tough one for Wikipedia — on Wednesday, a USA today editorial by John Seigenthaler called Wikipedia “irresponsible” for not catching significant mistakes in his biography, and Thursday, the Wikipedia community got up in arms after discovering that former MTV VJ and longtime podcaster Adam Curry had edited out references to other podcasters in an article about the medium.

In response to the hullabaloo, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales now plans to bar anonymous users from creating new articles. The change, which went into effect today, could possibly prevent a repeat of the Seigenthaler debacle; now that Wikipedia would have a record of who posted what, presumably people might be less likely to post potentially libelous material. According to Wales, almost all users who post to Wikipedia are already registered users, so this won’t represent a major change to Wikipedia in practice. Whether or not this is the beginning of a series of changes to Wikipedia that push it away from its “hive mind” origins remains to be seen.

I’ve been surprised at the amount of Wikipedia-bashing that’s occurred over the past few days. In a historical moment when there’s so much distortion of “official” information, there’s something peculiar about this sudden outrage over the unreliability of an open-source information system. Mostly, the conversation seems to have shifted how people think about Wikipedia. Once an information resource developed by and for “us,” it’s now an unreliable threat to the idea of truth imposed on us by an unholy alliance between “volunteer vandals” (Seigenthaler’s phrase) and the outlaw Jimmy Wales. This shift is exemplified by the post that begins a discussion of Wikipedia that took place over the past several days on the Association of Internet Researchers list serve. The scholar who posted suggested that researchers boycott Wikipedia and prohibit their students from using the site as well until Wikipedia develops “an appropriate way to monitor contributions.” In response, another poster noted that rather than boycotting Wikipedia, it might be better to monitor for the site — or better still, write for it.

Another comment worthy of consideration from that same discussion: in a post to the same AOIR listserve, Paul Jones notes that in the 1960s World Book Encyclopedia, RCA employees wrote the entry on television — scarcely mentioning television pioneer Philo Farnsworth, longtime nemesis of RCA. “Wikipedia’s failing are part of a public debate,” Jones writes, “Such was not the case with World Book to my knowledge.” In this regard, the flak over Wikipedia might be considered a good thing: at least it gives those concerned with the construction of facts the opportunity to debate with the issue. I’m just not sure that making Wikipedia the enemy contributes that much to the debate.

i am the person of the year

Time magazine is allowing anyone to submit photos of people they want to be “Person of the Year” to be projected on a billboard in Times Square. However, the website states that what they really want is to have people submit photos of themselves. All the photos that are selected to be projected will be photographed by webcam and their owners will be contacted. The images can be viewed, printed and sent to friends.

If the chance of seeing your image on a giant billboard in Times Square in real time is small, what is the difference between having Time photoshop your face onto its cover and doing it yourself? Is it the idea of projecting your image onto a billboard (which can be simulated as well)?

Is this Time magazine diminishing their role as information filter or it is an established news outlet recognizing the idea that anyone can be a publisher?

are we real or are we memorex

i saw four live performances and a dozen gallery shows over the past few days; one theme kept coming up– what is the relationship of simulated reality to reality. here are some highlights and weekend musings.

thursday night: “Supervision,” a play by the Builders Association and DBox about  the infosphere which seems to know more about us than we do — among other things “it” never forgets and rarely plays mash-up with our memories the way human brains are wont to do. the play didn’t shed much light on what we could or should do about the encroaching infosphere but there was one amazing moment when video started shooting from left to right across the blank wall behind the actors. within moments a complete set was “constructed” out of video projections — so seamlessy joined at the edges and so perfectly shot for the purpse that you quickly forgot you were looking at video.

the infosphere which seems to know more about us than we do — among other things “it” never forgets and rarely plays mash-up with our memories the way human brains are wont to do. the play didn’t shed much light on what we could or should do about the encroaching infosphere but there was one amazing moment when video started shooting from left to right across the blank wall behind the actors. within moments a complete set was “constructed” out of video projections — so seamlessy joined at the edges and so perfectly shot for the purpse that you quickly forgot you were looking at video.

friday night: Nu Voices six guys making amazing house music, including digitized-sounding vocals, entirely with their voices. one of the group, Masai Electro, eerily imitated the sounds laurie anderson makes with her vocoder or that DJs make when they process vocals to sound robotic. the crowd loved it which made me wonder why we are so excited about hearing a human pretend to be a machine? i asked masai electro why he thinks the audience likes what he does so much. he had never been asked the question before and evidently hadn’t thought about it, but then spontaneously answered “because that’s where we’re going” meaning that humans are becoming machines or at least are becoming “at one” with them.

saturday afternoon: Clifford Ross’ very large landscapes (13′ x 6′) made with a super high resolution surveillance camera. a modern attempt at hudson river school lush landscapes. because of the their size and detail, you feel as if you are looking out a window at reality; makes you long for the “natural world” most of us rarely encounter.

left with a bunch of questions

does it make a difference if our experience is “real” or “simulated.” does that way of looking at things even make sense anymore. when we manage to add the smell of fresh air, the sound of the wind, the rustle of the grass, the bird in flight and the ability to walk around in life-size 3-D spaces to the clifford ross photos, what will be the meaningful difference between walking in the countryside and opening the latest “you are there” coffee table book of the future. in a world with limited resources i can see the value of subsituting vicarious travel for the real thing (after all if all 7 billion of us traipsed out to the galapagos during our lifetimes, the “original” would be overrun and despoiled, turning it into its opposite). but what does it mean if almost all of our experience is technologically simulated and/or mediated?

Pedro Meyer in his comment about digitally altered photos says that all images are subjective which makes altered/not-altered a moot distinction. up until now the boundary between mediated objects and “reality” was pretty obvious, but i wonder if that changes when the scale is life-like and 3D. the Ross photos and the DBox video projections foreshadow life-size media which involves all the senses. the book of the future may not be something we hold in our hands, it might be something a 3-dimensional space we can inhabit. does it make any difference if i’m interacting only with simulacra?

IT IN place: muybridge meets typographic man

Alex Itin, friend and former institute artist-in-residence, continues to reinvent the blog as an art form over at IT IN place. Lately, Alex has been experimenting with that much-maligned motif of the early web, the animated GIF. Above: “My Bridge of Words.”

the role of note taking in the information age

An article by Ann Blair in a recent issue of Critical Inquiry (vol 31 no 1) discusses the changing conceptions of the function of note-taking from about the sixth century to the present, and ends with a speculation on the way that textual searches (such as Google Book Search) might change practices of note-taking in the twenty-first century. Blair argues that “one of the most significant shifts in the history of note taking” occured in the beginning of the twentieth century, when the use of notes as memorization aids gave way to the use of notes as a aid to replace the memorization of too-abundant information. With the advent of the net, she notes:

Today we delegate to sources that we consider authoritative the extraction of information on all but a few carefully specialized areas in which we cultivate direct experience and original research. New technologies increasingly enable us to delegate more tasks of remembering to the computer, in that shifting division of labor between human and thing. We have thus mechanized many research tasks. It is possible that further changes would affect even the existence of note taking. At a theoretical extreme, for example, if every text one wanted were constantly available for searching anew, perhaps the note itself, the selection made for later reuse, might play a less prominent role.

The result of this externalization, Blair notes, is that we come to think of long-term memory as something that is stored elsewhere, in “media outside the mind.” At the same time, she writes, “notes must be rememorated or absorbed in the short-term memory at least enough to be intelligently integrated into an argument; judgment can only be applied to experiences that are present to the mind.”

Blair’s article doesn’t say that this bifurcation between short-term and long-term memory is a problem: she simply observes it as a phenomenon. But there’s a resonance between Blair’s article and Naomi Baron’s recent Los Angeles Times piece on Google Book Search: both point to the fact that what we commonly have defined as scholarly reflection has increasingly become more and more a process of database management. Baron seems to see reflection and database management as being in tension, though I’m not completely convinced by her argument. Blair, less apocalyptic than Baron, nonetheless gives me something to ponder. What happens to us if (or when) all of our efforts to make the contents of our extrasomatic memory “present to our mind” happen without the mediation of notes? Blair’s piece focuses on the epistemology rather than the phenomenology of note taking — still, she leads me to wonder what happens if the mediating function of the note is lost, when the triangular relation between book, scholar and note becomes a relation between database and user.

machinima’s new wave

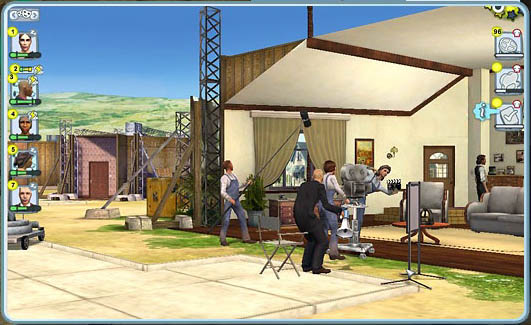

“The French Democracy” (also here) is a short film about the Paris riots made entirely inside of a computer game. The game, developed by Peter Molyneux‘s Lionhead Productions and called simply “The Movies,” throws players into the shark pool of Hollywood where they get to manage a studio, tangle with investors, hire and fire actors, and of course, produce and distribute movies. The interesting thing is that the movie-making element has taken on a life of its own as films produced inside the game have circulated through the web as free-standing works, generating their own little communities and fan bases.

This is a fascinating development in the brief history of Machinima, or “machine cinema,” a genre of films created inside the engines of popular video game like Halo and The Sims. Basically, you record your game play through a video out feed, edit the footage, and add music and voiceovers, ending up with a totally independent film, often in funny or surreal opposition to the nature of the original game. Bob, for instance, appeared in a Machinima talk show called This Spartan Life, where they talk about art, design and philosophy in the bizarre, apocalyptic landscapes of the Halo game series.

The difference here is that while Machinima is typically made by “hacking” the game engine, “The Movies” provides a dedicated tool kit for making video game-derived films. At the moment, it’s fairly primitive, and “The French Democracy” is not as smooth as other Machinima films that have painstakingly fitted voice and sound to create a seamless riff on the game world. The filmmaker is trying to do a lot with a very restricted set of motifs, unable to add his/her own soundtrack and voices, and having only the basic menu of locales, characters, and audio. The final product can feel rather disjointed, a grab bag of film clichés unevenly stitched together into a story. The dialogue comes only in subtitles that move a little too rapidly, Paris looks suspiciously like Manhattan, and the suburbs, with their split-level houses, are unmistakably American.

But the creative effort here is still quite astonishing. You feel you are seeing something in embryo that will eventually come into its own as a full-fledged art form. Already, “The Movies” online community is developing plug-ins for new props, characters, environments and sound. We can assume that the suite of tools, in this game and elsewhere, will only continue to improve until budding auteurs really do have a full virtual film studio at their disposal.

It’s important to note that, according to the game’s end-user license agreement, all movies made in “The Movies” are effectively owned by Activision, the game’s publisher. Filmmakers, then, can aspire to nothing more than pro-bono promotional work for the parent game. So for a truly independent form to emerge, there needs to be some sort of open-source machinima studio where raw game world material is submitted by a community for the express purpose of remixing. You get all the fantastic puppetry of the genre but with no strings attached.

killing the written word?

A November 28 Los Angeles Times editorial by American University linguistics professor Naomi Barron adds another element to the debate over Google Print [now called Google Book Search, though Baron does not use this name]: Baron claims that her students are already clamoring for the abridged, extracted texts and have begun to feel that book-reading is passe. She writes:

Much as automobiles discourage walking, with undeniable consequences for our health and girth, textual snippets-on-demand threaten our need for the larger works from which they are extracted… In an attempt to coax students to search inside real books rather than relying exclusively on the Web for sources, many professors require references to printed works alongside URLs. Now that those “real” full-length publications are increasingly available and searchable online, the distinction between tangible and virtual is evaporating…. Although [the debate over Google Print] is important for the law and the economy, it masks a challenge that some of us find even more troubling: Will effortless random access erode our collective respect for writing as a logical, linear process? Such respect matters because it undergirds modern education, which is premised on thought, evidence and analysis rather than memorization and dogma. Reading successive pages and chapters teaches us how to follow a sustained line of reasoning.

As someone who’s struggled to get students to go to the library while writing their papers, I think Baron’s making a very important and immediate pedagogical point: what will professors do after Google Book Search allows their students to access bits of “real books” online? Will we simply establish a policy of not allowing the online excerpted material to “count” in our tally of student’s assorted research materials?

On the other hand, I can see the benefits of having a student use Google Book Search in their attempt to compile an annotated bibliography for a research project, as long as they were then required to look at a version of the longer text (whether on or off-line). I’m not positive that “random effortless access” needs to be diametrically opposed to instilling the practice of sustained reading. Instead, I think we’ve got a major educational challenge on our hands whose exact dimensions won’t be clear until Google Book Search finally gets going.

Also: thanks to UVM English Professor Richard Parent for posting this article on his blog, which has some interesting ruminations on the future of the book.

insidious tactic #348: charge for web speed

An article in yesterday’s Washington Post — “Executive Wants to Charge for Web Speed” — brings us back to the question of pipes and the future of the internet.  The chief technology officer for Bell South says telecoms and cable companies ought to be allowed to offer priority deals to individual sites, charging them extra for faster connections. The Post:

The chief technology officer for Bell South says telecoms and cable companies ought to be allowed to offer priority deals to individual sites, charging them extra for faster connections. The Post:

Several big technology firms and public interest groups say that approach would enshrine Internet access providers as online toll booths, favoring certain content and shutting out small companies trying to compete with their offerings.

Among these “big technology firms” are Google, Yahoo!, Amazon and eBay, all of whom have pressed the FCC for strong “network neutrality” provisions in the latest round of updates to the 1996 Telecommunications Act. These would forbid discrimination by internet providers against certain kinds of content and services (i.e. the little guys). BellSouth claims to support the provisions, though the statements of its tech officer suggest otherwise.

Turning speed into a bargaining chip will undoubtedly privilege the richer, more powerful companies and stifle competition — hardly a net-neutral scenario. They claim it’s no different from an airline offering business class — it doesn’t prevent folks from riding coach and reaching their destination. But we all know how cramped and awful coach is. The truth is that the service providers discriminate against everyone on the web. We’re all just freeloaders leeching off their pipes. The only thing that separates Google from the lady blogging about her cat is how much money they can potentially pay for pipe rental. That’s where the “priorities” come in.

Moreover, the web is on its way to merging with cable television, and this, in turn, will increase the demand for faster connections that can handle heavy traffic. So “priority” status with the broadband providers will come at an ever increasing premium. That’s their ideal business model, allowing them to charge the highest tolls for the use of their infrastructure. That’s why the telecos and cablecos want to ensure, through speed-baiting and other screw-tightening tactics, that the net transforms from a messy democratic commons into a streamlined broadcast medium. Alternative media, video blogging, local video artists? These will not be “priorities” in the new internet. Maximum profit for pipe-holders will mean minimum diversity and a one-way web for us.

In a Business Week interview last month, SBC Telecommunications CEO Edward Whitacre expressed what seemed almost like a lust for revenge. Asked, “How concerned are you about Internet upstarts like Google, MSN, Vonage, and others?” he replied:

How do you think they’re going to get to customers? Through a broadband pipe. Cable companies have them. We have them. Now what they would like to do is use my pipes free, but I ain’t going to let them do that because we have spent this capital and we have to have a return on it. So there’s going to have to be some mechanism for these people who use these pipes to pay for the portion they’re using. Why should they be allowed to use my pipes?

The Internet can’t be free in that sense, because we and the cable companies have made an investment and for a Google or Yahoo! or Vonage or anybody to expect to use these pipes [for] free is nuts!

This makes me worry that discussions about “network neutrality” overlook a more fundamental problem: lack of competition. “That’s the voice of someone who doesn’t think he has any competitors,” says Susan Crawford, a cyberlaw and intellectual property professor at Cardozo Law School who blogs eloquently on these issues. She believes the strategy to promote network neutrality will ultimately fail because it accepts a status quo in which a handful of broadband monopolies dominate the market. “We need to find higher ground,” she says.

I think the real fight should be over rights of way and platform competition. There’s a clear lack of competition in the last mile — that’s where choice has to exist, and it doesn’t now. Even the FCC’s own figures reveal that cable modem and DSL providers are responsible for 98% of broadband access in the U.S., and two doesn’t make a pool. If the FCC is getting in the way of cross-platform competition, we need to fix that. In a sense, we need to look down — at the relationship between the provider and the customer — rather than up at the relationship between the provider and the bits it agrees to carry or block…

…Competition in the market for pipes has to be the issue to focus on, not the neutrality of those pipes once they have been installed. We’ll always lose when our argument sounds like asking a regulator to shape the business model of particular companies.

The broadband monopolies have their priorities figured out. Do we?

image: “explosion” (reminded me of fiber optic cable) by The Baboon, via Flickr