In a larger essay which bemoans the rise of image culture, Christine Rosen goes after Photoshop and its users in The New Atlantis, a right-leaning journal concerned with the intersection of technology and cultural values. According to Rosen, the software “democratizes the ability to commit fraud,” corrupting its users by giving them easy access to the tools of reality manipulation. She writes:

Photoshop has introduced a new fecklessness into our relationship with the image. We tend to lose respect for things we can manipulate. And when we can so readily manipulate images–even images of presidents or loved ones–we contribute to the decline of respect for what the image represents…

Worrying about photographic fakery isn’t new, of course — as Rosen herself notes, Susan Sontag inveighed against manipulated images in her 1977 work On Photography, and Rosen takes her point that images have been manipulated prior to the age of digitization. Here, however, Rosen’s concern with digital manipulation focuses less on the ability of people to deceive others with altered photos than on the ability of Photoshop to propel its users towards a general irreverence towards the real. This is an interesting inversion of the point that Bob Stein makes in a recent post; namely, that we have less respect for digitally manipulated images than ones which are “real.”

Later in the essay, Rosen suggests that some Photoshop images can be seen as the equivalent of today’s carnival sideshow:

“Photoshop contests” such as those found on the website Fark.com offer people the opportunity to create wacky and fantastic images that are then judged by others in cyberspace. This is an impulse that predates software and whose most enthusiastic American purveyor was, perhaps, P. T. Barnum. In the nineteenth century, Barnum barkered an infamous “mermaid woman” that was actually the moldering head of a monkey stitched onto the body of a fish. Photoshop allows us to employ pixels rather than taxidermy to achieve such fantasies, but the motivation for creating them is the same–they are a form of wish fulfillment and, at times, a vehicle for reinforcing our existing prejudices.

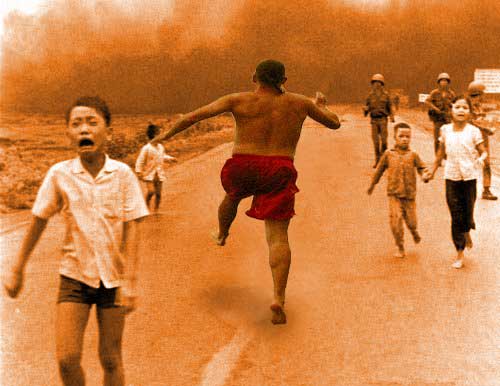

Looking at the Photoshop image above (which I pulled from the first Fark photoshop contest I came across), I can see the root of Rosen’s indignation: there is something offensive about the photo’s casual attitude toward an iconic image. But having seen similarly offensive editorial cartoons that riff on iconic phototographs, I’m not persuaded that Photoshop is the issue. It is true that without Photoshop this image would not have been made; indeed, as Rosen suggests, there is a Photoshop subculture on Fark that promotes the creation of absurd and often offensive images. But can we really make the argument that those who create these images become, in the process, less respectful of the reality they represent? I tend to resist such technological determinism: I would argue, against Rosen, that people manipulate images because they are already irreverent towards them — or, alternately, because they are cynical about the ability of images to represent truth.

Monthly Archives: November 2005

world digital library

The Library of Congress has announced plans for the creation of a World Digital Library, “a shared global undertaking” that will make a major chunk of its collection freely available online, along with contributions from other national libraries around the world. From The Washington Post:

The Library of Congress has announced plans for the creation of a World Digital Library, “a shared global undertaking” that will make a major chunk of its collection freely available online, along with contributions from other national libraries around the world. From The Washington Post:

…[the] goal is to bring together materials from the United States and Europe with precious items from Islamic nations stretching from Indonesia through Central and West Africa, as well as important materials from collections in East and South Asia.

Google has stepped forward as the first corporate donor, pledging $3 million to help get operations underway. At this point, there doesn’t appear to be any direct connection to Google’s Book Search program, though Google has been working with LOC to test and refine its book-scanning technology.

hmmm… online word processing

Not quite sure what I think of this new web-based word processor, Writely. Cute Web 2.0ish name, “beta” to the hilt. It’s free and quite easy to get started. I guess it falls into that weird zone of transitional unease between desktop computing and the wide open web, where more and more of our identity and information resides. Some of the tech specifics: Writely saves documents in Word and (as of today) Open Office formats, outputs as RSS and to some blogging platforms (not ours), and can also be saved as a simple web page (here’s the Writely version of this post). A key feature is that Writely documents can be written and edited by multiple authors, like SubEthaEdit only totally net-based. It feels more or less like a disembodied text editor for a wiki.

I’m trying to think about what’s different about writing online. Movable Type, our blogging software, is essentially an ultra-stripped-down text editor — web-based — and it’s no fun to work in. That’s partly because the text field is about the size of a mail slot, but writing online can be annoying for other reasons, chief among them the fact that you have to be online to work, and second that you are susceptible to the chance mishaps of the browser (accidentally backing up and losing everything, it crashes, you forgot to pay Time Warner and they turn off the web etc.). But with a conventional word processor you’re vulnerable to the mishaps of the machine (hard drive dies and you didn’t back it up, it crashes and you didn’t save, coffee spills…). Writely saves everything automatically as you go, maintaining a revision history and tracking changes — a very nice feature.

They say this is the future of software, at least for the simple everyday kind of stuff: web-based tool suites and tons of online data storage. I guess it’s nice not having to be tied to one machine. Your work is just out there, waiting for you to log in. But then again, your work is just out there…

online retail influencing libraries

The NY Times reports on new web-based services at university libraries that are incorporating features such as personalized recommendations, browsing histories, and email alerts, the sort of thing developed by online retailers like Amazon and Netflix to recreate some of the experience of browsing a physical store. Remember Ranganathan’s fourth law of library science: “save the time of the reader.” The reader and the customer are perhaps becoming one in the same.

It would be interesting if a social software system were emerging for libraries that allowed students and researchers to work alongside librarians in organizing the stacks. Automated recommendations are just the beginning. I’m talking more about value added by the readers themselves (Amazon has does this with reader reviews, Listmania, and So You’d Like To…). A social card catalogue with a tagging system and other reader-supplied metadata where readers could leave comments and bread crumb trails between books. Each card catalogue entry with its own blog and wiki to create a context for the book. Books are not just surrounded by other volumes on the shelves, they are surrounded by people, other points of view, affinities — the kinds of thing that up to this point were too vaporous to collect. This goes back to David Weinberger’s comment on metadata and Google Book Search.

beautiful? if so, why?

Sony Europe is promoting a new screen technology with a TV commercial featuring 250,000 brightly colored balls rolling down a San Francisco street. despite the maudlin soundtrack the sight of a quarter of a million balls floating chaotically down the hill is spectacular. this is partially because the piece is silly, fantastical, and brilliantly executed. i wonder though, if part of the reason people like the ad so much is because real balls are rolling on a real street — because the absence of any computer graphics is so unusual in our increasingly everything-so-neat-and-clean digital mediascape? this is not meant to be a rhetorical question. what do you think?

“open source media” — not the radio show — launches a best-bloggers site

On Wednesday, November 17, a media corporation called Open Source Media launched a portal site that intends to assemble the best bloggers on the internet in one place. According to the Associated Press, some 70 Web journalists, including Instapundit’s Glenn Reynolds and David Corn, Washington editor of the Nation magazine, have agreed to participate. The site will link to individual blog postings and highlight the best contributions in a special section: bloggers will be paid for content depending on the amount of traffic they generate.

Far from a seat-of-the-pants effort, OSM has $3.5 million dollars in venture capital funding. Supposedly, the site will pay for itself — and pay its bloggers — with the advertising it generates. In the “about” section of the site, the founders of OSM lay out their vision for remaking the future of blogging and media in general:

OSM’s mission is to expand the influence of weblogs by finding and promoting the best of them, providing bloggers with a forum to meet and share resources, and the chance to join a for-profit network that will give them additional leverage to pursue knowledge wherever they may find it. From academics, professionals and decorated experts, to ordinary citizens sitting around the house opining in their pajamas, our community of bloggers are among the most widely read and influential citizen journalists out there, and our roster will be expanding daily. We also plan to provide a bridge between old media and new, bringing bloggers and mainstream journalists–more and more of whom have started to blog–together in a debate-friendly forum.

We at if:book like the idea of a blog portal, especially one staffed by a series of editors selecting the best posts on the blogs they’ve chosen. But this venture — which fits perfectly with John Batelle’s vision for the web’s second coming — also seems to nicely embody the tension between doing good and making money: all that venture capital and overhead is going to put a lot of pressure on OSM to deliver the Oprah of the blogging world, if she’s out there. And paying bloggers based on how many readers they get is certainly going to shape the content that appears on the site. Unlike others who conceived of their blogs from the get-go as small businesses, most of the bloggers chosen by OSM haven’t been trying to make money from their blogs until now.

OSM also shot themselves in the foot by stealing the name of the newish public radio show Open Source Media, which we’ve written about here. The two are currently involved in a dispute over the name. and OSM hasn’t really been able to come up with a good reason why they should keep using a name that belongs to someone else. They have trademarked OSM, and they now refer to their unabbreviated name as “not a trade name,” but “a description of who we are and what we do.”

Needless to say, OSM has generated a fair amount of bad blood by appropriating the name of a nonprofit, and most of the grumbling has taken place in exactly the same place OSM hopes to make a difference — the blogosphere.

a better boom?

An editorial in today’s New York Times by The Search author Jon Battelle makes the argument that the current resurgence in technology stocks is not the sign of another technology “bubble,” but rather an indication that companies have finally figured out how to capitalize on the internet. Batelle writes:

… we are witnessing the Web’s second coming, and it’s even got a name, “Web 2.0” – although exactly what that moniker stands for is the topic of debate in the technology industry. For most it signifies a new way of starting and running companies – with less capital, more focus on the customer and a far more open business model when it comes to working with others. Archetypal Web 2.0 companies include Flickr, a photo sharing site; Bloglines, a blog reading service; and MySpace, a music and social networking site.

In other words, Batelle is pointing out that one way to “get it right” is not to sell content to users, but rather to give them the opportunity to create and search their own content. This is not only good business sense, he says, it’s also more enlightened — the creators of social software such as Flickr are motivated equally by a desire to “do good in the world” and a desire to make money. “The culture of Web 2.0 is, in fact, decidedly missionary,” Batelle writes, “from the communitarian ethos of Craigslist to Google’s informal motto, ‘don’t be evil.'”

O.K. Doing good while making money. Reading this, I’m reminded of Paul Hawken’s Natural Capitalism and the larger sustainability movement — the optimistic philosophy that weaves together environmental ethics and profitability. But is that what’s really going on here? Isn’t the “missionary” culture of the internet a bit OLDER than Web 2.0? Batelle is suggesting that Internet capitalists have gotten all misty and utopian; isn’t it the case that some of the folks who were already misty and utopian have just started making some money?

I guess the more viable comparison here would be to Marc Andreessen’s decision to transform his Mosaic browser from its public-domain University of Illinois incarnation into the Netscape Browser. Andreessen certainly started out as a browser missionary — and, like the companies Batelle sees as characteristic of Internet 2.0, Andreessen’s vision for Netscape (and in the beginning, Jim Clark’s vision as well) was a strong customer focus and open business model. What happened? Netscape’s meteoric success helped inflate the internet “bubble” Batelle’s referring to, and in the end, after the long battle with Microsoft, the company’s misfortunes helped to burst that bubble as well.

So what paradigm fits? Is “Internet 2.0” really new and more socially enlightened? Or are we just seeing a group of social software businesses — and one big search engine — just in the early stages of an inevitable transformation into corporations that are less interested in doing good than making money?

Incidentally, last month, Marc Andressen launched a social networking platform called Ning.

google print is no more

Not the program, of course, just the name. From now on it is to be known as Google Book Search. “Print” obviously struck a little too close to home with publishers and authors. On the company blog, they explain the shift in emphasis:

No, we don’t think that this new name will change what some folks think about this program. But we do believe it will help a lot of people understand better what we’re doing. We want to make all the world’s books discoverable and searchable online, and we hope this new name will help keep everyone focused on that important goal.

blogging and the true spirit of peer review

Slate goes to college this week with a series of articles on higher education in America, among them a good piece by Robert S. Boynton that makes the case for academic blogging:

“…academic blogging represents the fruition, not a betrayal, of the university’s ideals. One might argue that blogging is in fact the very embodiment of what the political philosopher Michael Oakshott once called “The Conversation of Mankind”–an endless, thoroughly democratic dialogue about the best ideas and artifacts of our culture.

…might blogging be subversive precisely because it makes real the very vision of intellectual life that the university has never managed to achieve?”

The idea of blogging as a kind of service or outreach is just beginning (maybe) to gain traction. But what about blogging as scholarship? Most professor-bloggers I’ve spoken with consider blogging an invaluable tool for working through ideas, for facilitating exchange within and across disciplines. Some go so far as to say that it’s redefined their lives as academics. But don’t count on tenure committees to feel the same. Blogging is vaporous, they’ll inevitably point out. Not edited, mixing the personal and the professional. How can you maintain standards and the appropriate barriers to entry? Traditionally, peer review has served this gatekeeping function, but can there be a peer review system for blogs? And if so, would we want one?

Boynton has a few ideas about how something like this could work (we’re also wrestling with these questions on our back porch blog, Sidebar, with the eventual aim of making some sort of formal proposal). Whatever the technicalities, the approach should be to establish a middle path, something like peer review, but not a literal transposition. Some way to gauge and recognize the intellectual rigor of academic blogs without compromising their refreshing immediacy and individuality — without crashing the party as it were.

There’s already a sort of peer review going on among blog carnivals, the periodicals of the blogosphere. Carnivals are rotating showcases of exemplary blog writing in specific disciplines — history, philosophy, science, education, and many, many more, some quite eccentric. Like blogs, carnivals suffer from an unfortunate coinage. But even with a snootier name — blog symposiums maybe — you would never in a million years confuse them with an official-looking peer review journal. Yet the carnivals practice peer review in its most essential form: the gathering of one’s fellows (in this case academics and non-scholar enthusiasts alike) to collectively evaluate (ok, perhaps “savor” is more appropriate) a range of intellectual labors in a given area. Boynton:

In the end, peer review is just that: review by one’s peers. Any particular system should be judged by its efficiency and efficacy, and not by the perceived prestige of the publication in which the work appears.

If anything, blog-influenced practices like these might reclaim for intellectuals the true spirit of peer review, which, as Harvard University Press editor Lindsay Waters has argued, has been all but outsourced to prestigious university presses and journals. Experimenting with open-source methods of judgment–whether of straight scholarship or academic blogs–might actually revitalize academic writing.

It’s unfortunate that the accepted avenues of academic publishing — peer-reviewed journals and monographs — purchase prestige and job security usually at the expense of readership. It suggests an institutional bias in the academy against public intellectualism and in favor of kind of monastic seclusion (no doubt part of the legacy of this last great medieval institution). Nowhere is this more apparent than in the language of academic writing: opaque, convoluted, studded with jargon, its remoteness from ordinary human speech the surest sign of the author’s membership in the academic elite.

This crisis of clarity is paired with a crisis of opportunity, as severe financial pressures on university presses are reducing the number of options for professors to get published in the approved ways. What’s needed is an alternative outlet alongside traditional scholarly publishing, something between a casual, off-the-cuff web diary and a polished academic journal. Carnivals probably aren’t the solution, but something descended from them might well be.

It will be to the benefit of society if blogging can be claimed, sharpened and leveraged as a recognized scholarly practice, a way to merge the academy with the traffic of the real world. The university shouldn’t keep its talents locked up within a faltering publishing system that narrows rather than expands their scope. That’s not to say professors shouldn’t keep writing papers, books and monographs, shouldn’t continue to deepen the well of knowledge. On the contrary, blogging should be viewed only as a complement to research and teaching, not a replacement. But as such, it has the potential to breathe new life into the scholarly enterprise as a whole, just as Boynton describes.

Things move quickly — too quickly — in the media-saturated society. To remain vital, the academy needs to stick its neck out into the current, with the confidence that it won’t be swept away. What’s theory, after all, without practice? It’s always been publish or perish inside the academy, but these days on the outside, it’s more about self-publish. A small but growing group of academics have grasped this and are now in the process of inventing the future of their profession.

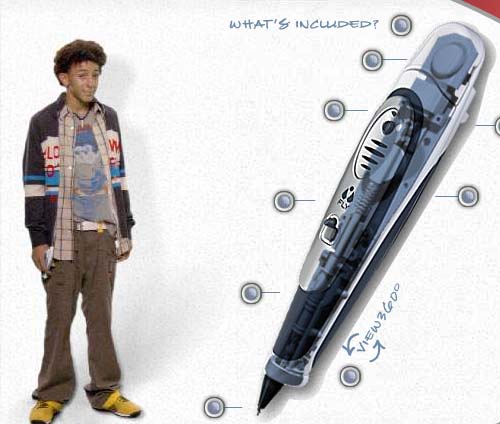

the fly — a hundred dollar “pentop” for the overdeveloped world

Two products that will most likely never be owned by the same teenager: The hundred dollar Laptop from MIT and the hundred dollar “pentop” computerized pen called the Fly. While the hundred dollar laptop (as we’ve said a few times on this site already) is promoted as a device to bring children of underdeveloped countries into the silicon era, the Fly is a device that will help technology-saturated 8 to 14 year olds keep track of soccer practice, learn to read, and solve arithmetic equations. Equipped with a microphone and OCR software, the Fly will read aloud what you write: if you use the special paper that comes with the product, you can draw a calculator and the calculator becomes functional. It’s all very Harold and the Purple Crayon .

Two products that will most likely never be owned by the same teenager: The hundred dollar Laptop from MIT and the hundred dollar “pentop” computerized pen called the Fly. While the hundred dollar laptop (as we’ve said a few times on this site already) is promoted as a device to bring children of underdeveloped countries into the silicon era, the Fly is a device that will help technology-saturated 8 to 14 year olds keep track of soccer practice, learn to read, and solve arithmetic equations. Equipped with a microphone and OCR software, the Fly will read aloud what you write: if you use the special paper that comes with the product, you can draw a calculator and the calculator becomes functional. It’s all very Harold and the Purple Crayon .

In his review of the Fly’s capabilities in todays New York Times, David Pogue is largely enthusiastic about the device, finding it both practical and appealing (if a tad buggy in its original version). Most of all, he seems to think the Fly’s too-cool-for-school additional features are necessary innovation in a market that he says has begun to dry up — digital educational products for children. According to Pogue:

When it comes to children’s technology, a sort of post-educational age has dawned. Last year, Americans bought only one-third as much educational software as they did in 2000. Once highflying children’s software companies have dwindled or disappeared. The magazine once called Children’s Software Review is now named Children’s Technology Review, and over half of its coverage now is dedicated to entertainment titles (for Game Boy, PlayStation and the like) that have no educational component.

If Pogue is right, and educational software is on its way out, does this mean that everything has moved over to the web? And what implication does this downturn have for the hundred dollar laptop project?