I wasn’t surprised by two adverse reactions to the blog entry “The Book is Doomed”; scary news for a lot of people. Think about the jargon embedded in those pieces that deal with e-books, or the cryptic messages that pop-up on the screen when the uninitiated tries to access an actual e-book… In order to read a paper book one doesn’t need to know proofreader’s marks or bookbinding jargon. So, a paper book is friendly. At this point, that seems to be the approach almost anyone takes to the idea of a different kind of book. Even audio books have their detractors, those who say that listening to a book isn’t the same as reading a book.

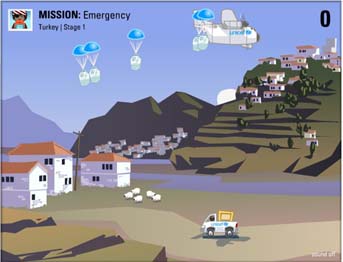

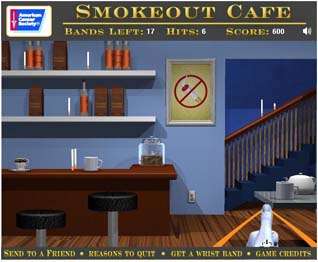

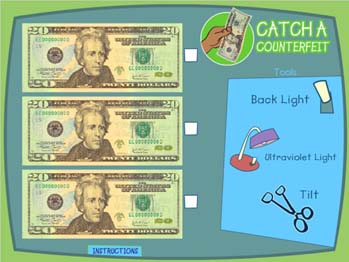

A couple of news in last week’s Times made me think of issues not yet addressed by the Institute’s site. One is the prevalence of videogames in the lives of children and the fact that the “future of the book” really belongs to those children. For me, finding hot and dusty Internet cafes in the oases of the Tlakamakan desert was, in a way, unexpected. Finding those places full of school-age children playing videogames was a revelation. In “Is Instructional Video Game an Oxymoron?” Matt Richtel talks about nonprofit organizations adopting the game format to advance their agenda. “For the current generation, the Net is the medium, and the message includes ‘Become a Unicef World Hero,’ as conveyed by a game on the unicefgames.org site. He also mentions a shooting gallery game from the American Cancer Society that “lets players flip virtual rubber bands at passing cigarettes in the Smokeout Café,” or the Greenpeace site, where “players can intercept harpoons fired from a Japanese whaling ship – or, by getting three ‘activists’ aboard the ship, force its crew to surrender.” The Bureau of Engraving and Printing lets youngsters color and design currency while learning to spot counterfeits.

“Through online games, we’re teaching a whole generation to authenticate their currency,” said Dawn Haley, a spokeswoman. “It was one easy way to get children involved. Gaming is huge these days.”

What they are doing is updating the old didactic tradition of using games to teach, they are teaching in the digital age. That brings me to my second thought, is the future of the book the domain of brainy sophisticates or is it a democratic move? In “New Economy; At Davos, the Johnny Appleseed of the Digital Era Shares his Ambition to Propagate a $100 Laptop in Developing Countries,” they mention that Nicholas Negroponte in partnership with Joseph Jacobson, a physicist at M.I.T., wants to persuade the education ministries of countries like China to use laptops to replace textbooks (see also Laptops for the Masses on this blog). At Davos, Negroponte said that he found initial backing for his laptop plan from Advanced Micro Devices and that he was in discussions with Google, Motorola, the News Corporation and Samsung for support. “You can just give laptops to kids,” he said referring to an experiment in Cambodia. “In Cambodia, the first English word out of their mouths is ‘Google.'” In my opinion that is/should be the future of the book.

What they are doing is updating the old didactic tradition of using games to teach, they are teaching in the digital age. That brings me to my second thought, is the future of the book the domain of brainy sophisticates or is it a democratic move? In “New Economy; At Davos, the Johnny Appleseed of the Digital Era Shares his Ambition to Propagate a $100 Laptop in Developing Countries,” they mention that Nicholas Negroponte in partnership with Joseph Jacobson, a physicist at M.I.T., wants to persuade the education ministries of countries like China to use laptops to replace textbooks (see also Laptops for the Masses on this blog). At Davos, Negroponte said that he found initial backing for his laptop plan from Advanced Micro Devices and that he was in discussions with Google, Motorola, the News Corporation and Samsung for support. “You can just give laptops to kids,” he said referring to an experiment in Cambodia. “In Cambodia, the first English word out of their mouths is ‘Google.'” In my opinion that is/should be the future of the book.

(photograph: girls at the Elaine and Nicholas Negroponte School in Cambodia)

Monthly Archives: February 2005

laptops for the masses

MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte is developing a line of laptop computers that will sell for less than $100 a piece. The textbook of the future?….

>>BBC article

little red book

Very interesting review of McKenzie Wark‘s A Hacker Manifesto, recently published by Harvard University Press. In the manifesto (shorter version), Wark outlines a class struggle over “vectors” – the information channels of a society. In his words:

![]() “With the commodification of information comes its vectoralisation. Extracting a surplus from information requires technologies capable of transporting information through space, but also through time. The archive is a vector through time just as communication is a vector that crosses space. The vectoral class comes into its own once it is in possession of powerful technologies for vectoralising information.–The vectoral class may commodify information stocks, flows, or vectors themselves. A stock of information is an archive, a body of information maintained through time that has enduring value. A flow of information is the capacity to extract information of temporary value out of events and to distribute it widely and quickly. A vector is the means of achieving either the temporal distribution of a stock, or the spatial distribution of a flow of information. Vectoral power is generally sought through the ownership of all three aspects.”

“With the commodification of information comes its vectoralisation. Extracting a surplus from information requires technologies capable of transporting information through space, but also through time. The archive is a vector through time just as communication is a vector that crosses space. The vectoral class comes into its own once it is in possession of powerful technologies for vectoralising information.–The vectoral class may commodify information stocks, flows, or vectors themselves. A stock of information is an archive, a body of information maintained through time that has enduring value. A flow of information is the capacity to extract information of temporary value out of events and to distribute it widely and quickly. A vector is the means of achieving either the temporal distribution of a stock, or the spatial distribution of a flow of information. Vectoral power is generally sought through the ownership of all three aspects.”

collecting and archiving the future book

The collection and preservation of digital artworks has been a significant issue for museum curators for many years now. The digital book will likely present librarians with similar challenges, so it seems useful to look briefly at what curators have been grappling with.

At the Decade of Web Design Conference hosted by the Institute for Networked Cultures. Franziska Nori spoke about her experience as researcher and curator of digital culture for digitalcraft at the Museum for Applied Art in Frankfurt am Main. The project set out to document digital craft as a cultural trend. Digital crafts were defined as “digital objects from everyday life,” mostly websites. Collecting and preserving these ephemeral, ever-changing objects was difficult, at best. A choice had to be made between manual selection, or automatic harvesting. Nori and her associates chose manual selection. The advantage of manual selection was that critical faculties could be employed. The disadvantage was that subjective evaluations regarding an object’s relevance were not always accurate, and important work might be left out. If we begin to treat blogs, websites, and other electronic ephemera as cultural output worthy of preservation and study (i.e. as books), we will have to find solutions to similar problems.

The pace at which technology renews and outdates presents a further obstacle. There are, currently, two ways to approach durability of access to content. The first, is to collect and preserve hardware and software platforms, but this is extremely expensive and difficult to manage. The second solution, is to emulate the project in updated software. In some cases, the artist must write specs for the project, so it can be recreated at a later date. Both these solutions are clearly impractical for digital librarians who must manage hundreds of thousand of objects. One possible solution for libraries, is to encourage proliferation of objects. Open source technology might make it possible for institutions to share data/objects, thus creating “back-up” systems for fragile digital archives.

Nori ended her presentation with two observations. “Most societies create their identity through an awareness of their history.” This, she argues, compells us to find ways to preserve digital communications for posterity. She notes that cultural historians, artists, and researchers “are worried about a future where these artifacts will not be accessible.”

the tomorrow book

“The Jan van Eyck Academie and the Charles Nypels Foundation invite designers, book critics, book theoreticians and book makers to submit project proposals in the context of the research project ‘The tomorrow book. Navigating to, within and beyond the book’. ‘The tomorrow book’ intends to query the future of the book from a multi-disciplinary standpoint. In doing so, the following aspects will be treated: editing, typography, book design, publishing and distribution. The umbrella theme of the project is navigation towards, inside and outside of the book. Research candidates can submit project proposals for ‘The tomorrow book’ up to 15 April 2005.”

“The Jan van Eyck Academie and the Charles Nypels Foundation invite designers, book critics, book theoreticians and book makers to submit project proposals in the context of the research project ‘The tomorrow book. Navigating to, within and beyond the book’. ‘The tomorrow book’ intends to query the future of the book from a multi-disciplinary standpoint. In doing so, the following aspects will be treated: editing, typography, book design, publishing and distribution. The umbrella theme of the project is navigation towards, inside and outside of the book. Research candidates can submit project proposals for ‘The tomorrow book’ up to 15 April 2005.”

More information on “the tomorrow book” research…

from aspen to A9

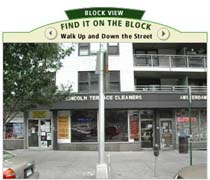

Amazon’s search engine A9 has recently unveiled a new service: yellow pages “like you’ve never seen before.”

“Using trucks equipped with digital cameras, global positioning system (GPS) receivers, and proprietary software and hardware, A9.com drove tens of thousands of miles capturing images and matching them with businesses and the way they look from the street.”

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

I can imagine online services like Mapquest getting into, or wanting to get into, this kind of image-banking. But I wouldn’t expect trucks with camera mounts to become a common sight on city streets. More likely, A9 is building up a first-run image bank to demonstrate what is possible. As people catch on, it would seem only natural that they would start accepting user contributions.  Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

A9’s new service does have a predecessor though, and it’s nearly 30 years old. In the late 70s, the Architecture Machine Group, which later morphed into the MIT Media Lab, developed some of the first prototypes of “interactive media.” Among them was the Aspen Movie Map, developed in 1978-79 by Andrew Lippman – a program that allowed the user to navigate the entirety of this small Colorado city, in whatever order they chose, in winter, spring, summer or fall, and even permitting them to enter many of the buildings. The Movie Map is generally viewed as the first truly interactive computer program. Now, with the explosion of digital photography, wireless networked devices, and image-caching across social networks, we might at last be nearing its realization on a grand scale.

what’s at stake

High-definition TV pioneer and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban talks about what’s at stake in the upcoming Supreme Court case MGM vs. Grokster in an article drawn from a recent post on his blog.  Skip down to the section titled “Taking a Wrong Turn.” There, Cuban describes what could be lost if entertainment industry giants are able to convince the court that peer-to-peer file sharing is first and foremost a tool for theft.

Skip down to the section titled “Taking a Wrong Turn.” There, Cuban describes what could be lost if entertainment industry giants are able to convince the court that peer-to-peer file sharing is first and foremost a tool for theft.

“In the MGM v. Grokster case, the fewer than 50 companies who control less than 1 percent of all digital information are trying to take control of innovation in the technology industry and pry it away from the rest of us. Everything our imagination creates and touches that can be made digital is at risk if Grokster loses.

“What innovations will be condemned by law before they have a chance to come to market, because they could have an impact on Hollywood and the music industry? We have no idea, and that is a very scary prospect.”

the performing book

We’ve been talking about reading modes, but let’s imagine, for a moment, that the future book will change reading itself. Perhaps it will combine the performance aspects of television, film, animation, and theatre with the interactive aspects of the world wide web to forge a book that reads you as you read it.

Science fiction writer Neal Stephenson imagines such a book in his novel, The Diamond Age. The main character is a book–an illustrated primer that functions almost like an artificial intelligence. It bonds with its reader, notices things about her life, and uses those bits of information to create instructional narratives on the fly. These stories are performed by live “ractors” (human actors working in reactive/interactive scenarios) and broadcast on the pages of a book. The physical book is leather bound, with “smart” paper pages that support electronic text and animated images. The primer looks like an old-fashioned book, but acts (or reacts) like a book of the future. In Stephenson’s imagination, it’s this element of interactivity and performance that distinguishes the future book from its predecessor.

But lest you worry that I’m basing my research on the imaginings of my favorite science fiction writer, I can assure you that the performing book is already here in its nascent incarnations. In the image of Stephenson’s primer, a company called Touchsmart is developing a book with “smart” paper that functions like a touch screen, allowing readers to find answers to their questions instantly, through a wireless connection to the internet and to other electronic devices that broadcast content.

Publisher, Peak Interactive Books, whose stated mission is to, look beyond the print book, beyond television, beyond the web page, to the interactive book of the future, is publishing interactive multimedia textbooks including: Cryosurgery for Prostate Cancer, and Using Interactive Media to Communicate.

The interactive CD Roms published by Voyager are an excellent touchstone in the history of performing books. TK3 software, which has been used to make everything from textbooks, to performing paintings, also draws on the performing book model. The institute is presently developing “Sophie,” ebook authoring software that will allow most currently available media to be incorporated into an electronic book.

As for the book reading you. Ben’s recent post “finally, I have a Memex!” describes how the semantic web will add a new dimension to the growing power of search engines. Their ability to collect personal information has already been incorporated into the recreational and academic reading experience. What we are waiting for is the book that builds its content out of the bits it gathers from our lives.

incredible shrinking book

A couple morsels today on textually.org lending credence to our theory that cellphones/PDAs are the incubation niche for the eventual widespread adoption of ebooks. One on fashionable new casings Nokia is bringing out for mobile devices (re Kim’s leather-bound fantasy ebook). Another on plans by Chinese tech giant Lenovo to embed “mobile book software technology” into phones, allowing users to read fully illustrated books, as well as watch movies, listen to audio, play video games, and browse periodicals. Mobile phones are emerging, at least in China, as the ultimate mass-consumer media processor – affordable and eminently portable. And each year, notebook computers become lighter, sleeker, and easier to tote around. Are they just shrinking into palm pilots? How much serious work can you get done on a palm pilot?

A couple morsels today on textually.org lending credence to our theory that cellphones/PDAs are the incubation niche for the eventual widespread adoption of ebooks. One on fashionable new casings Nokia is bringing out for mobile devices (re Kim’s leather-bound fantasy ebook). Another on plans by Chinese tech giant Lenovo to embed “mobile book software technology” into phones, allowing users to read fully illustrated books, as well as watch movies, listen to audio, play video games, and browse periodicals. Mobile phones are emerging, at least in China, as the ultimate mass-consumer media processor – affordable and eminently portable. And each year, notebook computers become lighter, sleeker, and easier to tote around. Are they just shrinking into palm pilots? How much serious work can you get done on a palm pilot?

“finally, I have a Memex!”

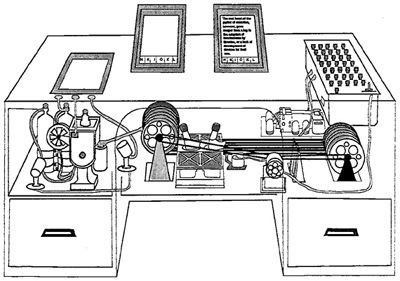

There’s an essay worth reading in the ny times book review this past sunday by Steven Johnson about a powerful semantic desktop management and search tool recently released for Macs.  The software (called DEVONthink) not only helps organize and briskly sift through readings, clippings, quotes, and one’s own past writings, but assists in the mysterious mental processes that are at the heart of writing – associative trains, useful non sequiturs, serendipitous stumbles. In effect, we now have a tool resembling the Memex device described in the seminal 1945 essay, As We May Think by visionary engineer Vannevar Bush. Working with the cutting edge technologies of his day – microfilm, thermionic tubes, and punch, or “Hollerith,” cards – Bush pondered how technology might help humanity to manage and make use of its vast systems of information. His recognition of the basic problem is no less relevant today: “Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing.” Fast forward to 2005. Now, the holy grail of search is the Semantic Web – moving beyond the artificiality of crude content-based queries and bringing meaning, relevance, and associations into the mix.

The software (called DEVONthink) not only helps organize and briskly sift through readings, clippings, quotes, and one’s own past writings, but assists in the mysterious mental processes that are at the heart of writing – associative trains, useful non sequiturs, serendipitous stumbles. In effect, we now have a tool resembling the Memex device described in the seminal 1945 essay, As We May Think by visionary engineer Vannevar Bush. Working with the cutting edge technologies of his day – microfilm, thermionic tubes, and punch, or “Hollerith,” cards – Bush pondered how technology might help humanity to manage and make use of its vast systems of information. His recognition of the basic problem is no less relevant today: “Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing.” Fast forward to 2005. Now, the holy grail of search is the Semantic Web – moving beyond the artificiality of crude content-based queries and bringing meaning, relevance, and associations into the mix.

“Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.” – Vannevar Bush

It’s quite suggestive that DEVONthink’s semantic search function can to an extent be trained, taking the obnoxious little puppy on Windows search toward its full potential – a sleek, truffle-tuned hound. When Johnson loads his body of work onto the computer, the hound picks up the distinctive scent of his writing, which in turn suggests affinities, similarities, and connections to other materials – truffles – that will find their way into later works.

Says Johnson on his latest blog post, which goes into much greater detail than the Times piece:

Says Johnson on his latest blog post, which goes into much greater detail than the Times piece:“I have pre-filtered the results by selecting quotes that interest me, and by archiving my own prose. The signal-to-noise ratio is so high because I’ve eliminated 99% of the noise on my own.”

But it is significant that DEVONthink is not useful for searching entire books (the author’s own manuscripts notwithstanding). Currently, the tool is ideal for locating chunks of text that fall within the “sweet spot” of 50-500 words. If your archives include entire book-length texts, then the honing power is diminished. DEVONthink is optimal as a clip searcher. File searching remains a frustrating enterprise.

Johnson makes note of this:

“So the proper unit for this kind of exploratory, semantic search is not the file, but rather something else, something I don’t quite have a word for: a chunk or cluster of text, something close to those little quotes that I’ve assembled in DevonThink. If I have an eBook of Manual DeLanda’s on my hard drive, and I search for “urban ecosystem” I don’t want the software to tell me that an entire book is related to my query. I want the software to tell me that these five separate paragraphs from this book are relevant. Until the tools can break out those smaller units on their own, I’ll still be assembling my research library by hand in DevonThink.”

Another point (from the Times piece) worth highlighting here, which relates to our discussion of the networked book:

“If these tools do get adopted, will they affect the kinds of books and essays people write? I suspect they might, because they are not as helpful to narratives or linear arguments; they’re associative tools ultimately. They don’t do cause-and-effect as well as they do ‘x reminds me of y.’ So they’re ideally suited for books organized around ideas rather than single narrative threads: more ‘Lives of a Cell’ and ‘The Tipping Point’ than ‘Seabiscuit.'”

And what about other forms of information – images, video, sound etc.? These media will come to play a larger role in the writing process, given the ease of processing them in a PC/web context. Images and music trump language in their associative power (a controversial assertion, please debate it!), and present us with layers of meaning that are harder to dissect, certainly by machine. It is an inchoate hound to be sure.

And what about other forms of information – images, video, sound etc.? These media will come to play a larger role in the writing process, given the ease of processing them in a PC/web context. Images and music trump language in their associative power (a controversial assertion, please debate it!), and present us with layers of meaning that are harder to dissect, certainly by machine. It is an inchoate hound to be sure.